The craft of timber framing begins in the forest. What happens in the forest has a lot to do with what happens in the sawmill, the hewing yard, and in your house. If you spend time walking and working in the forest, your knowledge of the forest will improve your craft. Many framers cannot tell which end of a beam was up in the tree or what species of wood they are working.

The first step in finding trees suitable for beams is to pick up a field guide to the trees in your region and spend some time in the woods getting to know the species around you. Try to determine which ones are abundant and which ones grow straight. Learn to identify trees by their bark and shape because much wood harvesting is done in the winter. If possible, find out what the early settlers of your area typically used. Most people assume that oak was the prime species used for timber frames in the past, but even in oak’s natural range it wasn’t the only species used. In much of northern New England, early framers typically used beech and spruce. Most people cannot identify the species of wood in an old frame: I have heard so-called experts call a spruce frame chestnut. Refer to R. Bruce Hoadley’s Identifying Wood (1990) to learn how to correctly identify species in frames. In their rough order of abundance, I have seen old frames of white oak, American beech, white pine, red spruce, hemlock, pitch pine, American chestnut, sugar maple, baldcypress, elm, aspen (poplar), basswood, yellow birch, white birch, white ash, and hophornbeam.

To understand the craft of timber framing completely, you must learn from the forest.

The English colonists that settled along the Atlantic coast found white oak in abundance. It was very strong and very rot resistant and fairly similar to the oak that they had been working in England. The first-generation American house frames were typically white oak. By 1700, framers began using other species in their frames. As settlers pushed inland and found other forest types, they selected the best of what species were available locally.

The old-growth forests in my area included the sugar maple/beech/yellow birch hardwood forest as well as softwoods like red spruce, hemlock, and white pine. Here is an old yellow birch tree.

In their homeland, the Dutch worked with many species, using softwoods imported from the Baltic and Scandinavian countries and with oak imported from Germany. The Dutch used their own oak sparingly — when available — for elements that required durability. Mixed local timber of poorer quality was used for lesser buildings.

In America, the Dutch found both hardwoods and softwoods in abundance. Oak posts might support pine anchor-beams and plates. In eighteenth-century Dutch barns, I’ve seen huge elm anchor-beams, 40-foot basswood plates, and poplar rafters. Some frames were entirely of pitch pine, a hard southern yellow pine that grew to immense size in the sandy bottomlands along the Hudson and Mohawk rivers. They also commonly used eastern white pine and eastern hemlock.

Base your selection of timber for your house on the following factors:

Local availability and abundance

Local availability and abundance

Ease of working

Ease of working

Durability, stability, and rot resistance (especially for sills)

Durability, stability, and rot resistance (especially for sills)

Cost (some species may be expensive)

Cost (some species may be expensive)

I recommend using a mixture of several species. Place highly rot-resistant species where necessary. I suggest using hardwoods for braces and softwoods for the longer members. Remember that you will learn much more about wood if you work several species. My first frame contains twenty different species and my house has fourteen. Over the years I’ve worked more than fifty species of timbers. You needn’t worry about the aesthetics of mixing species. With the exception of extremely dark- or light-colored woods, most unfinished woods look remarkably similar in color. Visitors to my house often comment that the frame is all white pine as they stare at white oak, red oak, beech, black birch, and ash timbers. If you have some colorful species like black walnut or black cherry, arrange the pieces in a logical and artistic fashion.

Each species has unique advantages and drawbacks. The following section describes the more common species in the Northeast that I have experience with. It is by no means inclusive of all the workable species — draw upon local resources if you want to work a wood that isn’t listed by asking a local framer and seeing if the older structures in your area used that species. You can also refer to the Wood Handbook (USDA 1974) for more specifics on appropriate regional species.

American Basswood, Tilia americana: Though not common in old frames, basswood was used occasionally. A Dutch barn in Warnerville, New York, had a pair of 40-foot long basswood plates. The trees grow quite straight with clear, branchless trunks for much of their height. Basswood’s soft, even-grained wood works easily but has no decay resistance and little figure.

American Beech, Fagus grandifolia: A large, smooth, grey-barked tree common in the northern hardwood forest. From the study of old timber-framed buildings, beech appears to have been the wood of choice in those areas dominated by the northern hardwood forest. It has dense, even grained, and very strong wood, though it is very workable. Beech hews wonderfully and joints are easily pared across the grain without tearing. Because it is fine grained, it can be planed extremely smooth. The sapwood is a creamy color while the heartwood is tan or brownish. It is not rot resistant, so limit its use away from moist locations. It is particularly prone to attack by powder-post beetles and carpenter ants in damp areas. It has a high rate of shrinkage, which will show in your joinery.

The author’s house frame has fourteen different species of timbers, most of them cut on-site.

These old beech timbers exhibit the tell-tale holes of powder-post beetles, though they are still in good condition.

Beech has excellent resistance to wear. In fact, the more you rub it, the smoother and more wear resistant it becomes — it was a popular choice for wooden machinery such as gear teeth, shafts, bearings, and items such as sled runners, wooden planes, rolling pins, door hinges, and mallets.

Since the late 1960s, beeches have been hit hard by a fungus that erupts their smooth bark and subsequently kills them. As a result, there is a great deal of beech being harvested at a reasonable price. And though at the time of this writing there are still many fine beeches standing, it might be honorable to use more beech timber in house frames in case the species suffers the decimation that befell the chestnut.

American Elm, Ulmus americana: Today, elm has a bad reputation for being difficult to work. Many people even avoid using elm for firewood because it splits so poorly. But old framers occasionally used elm timbers, especially in England. I’ve seen 12-inch by 20-inch hewn elm anchorbeams in some New York Dutch barns. Apparently, straight, virgin forest specimens were not that hard to work. In addition, its grain patterns are unusual and attractive. Because this tree has been hit hard by Dutch elm disease, it is being cut heavily and logs are available. It would be nice to work some elm before it is all gone.

Balsam Fir, Abies balsamea: Balsam fir typically grows along with red spruce in the northern forests though it is not as long lived. It grows very straight with only small branches and little taper. The heart is often rotted on the larger specimens. Its wood is practically indistinguishable from that of red spruce but is less strong. Balsam fir is not decay resistant.

Bigtooth Aspen, Populus grandidentata: Often referred to as popple or poplar, this tree grows very fast and often has straight, clear trunks. The creamy white wood works easily and because it is about equal to eastern white pine in strength, it can be used for the hall-and-parlor house. It has no rot resistance.

Black Birch, Betula lenta: Also called sweet birch, black birch is the strongest of the birches and is even stronger than most oaks. I am not sure if framers often built with black birch in the past, but it is serviceable nonetheless. It has a reddish brown heartwood and a distinctive wintergreen aroma when freshly cut. Birches are not rot resistant.

Black Cherry, Prunus serotina: Although it was uncommon in old frames, I include black cherry here because of its high resistance to decay. In the northern hardwood forest, it may be the only rot-resistant species available. Most think of cherry as a yard tree, but this native cherry reaches timber size in much of the Northeast. In old-growth forests, black cherry grows to 3 feet in diameter and over 100 feet high. Larger specimens should be reserved for furniture, but smaller, lower-grade timber-size trees abound in many areas. The even grain and aromatic scent are a pleasure to work and its color can accent a light-colored wood frame.

Working stress figures are not available for black cherry at this time, but it is stronger than white pine and you can substitute it in our frame design. I often cut sill timbers from black cherry. In parts of the Northeast, it is inexpensive and common locally.

Black Locust, Robinia pseudoacacia: A very strong, hard, and heavy wood that is very resistant to decay. Black locust has a moderately low rate of shrinkage for such a heavy wood. Though logs tend to be more wavy than straight, it is still workable. I recommend black locust for sills and timbers exposed to the weather. Work it when green as it is much harder to work when dry.

Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis: Hemlock was commonly used in the Northeast for both timbers and wall planking. When green, hemlock is heavy but works easily; when dry, it is fairly light but difficult to work. Hemlock’s biggest drawback is that it tends to have a lot of shakes. Since hemlock also forms terrible splinters, I often relegate it to areas of the house where hands won’t touch it.

Eastern White Pine, Pinus strobus: This is the largest-growing conifer in the Northeast. In the past, specimens grew up to 260 feet in height and 10 feet in diameter, though trees of half that size are rare today. There are still pines in Michigan that top 200 feet. It was used extensively for timbers, planks, boards, shingles, clapboards, moldings, cabinets, doors, trim, and ship’s masts. White pine is very stable and has one of the lowest shrinkage rates of northeastern trees. It is also moderately rot resistant. Because white pines grow tall and straight, long timbers are easily procured. It has to be one of the easiest-working woods available and where it is abundant, one of the least expensive. Because it branches in tiers called whorls, the timbers will have intervals of knots, usually with clear wood between whorls. The distance between whorls may range from 6 inches to 4 feet, depending on growth conditions. Because knots are concentrated at the whorls, the timber is weakened there and joinery should be located in the clear wood areas if possible. Even branchy white pines are useful if they are sufficiently large as the clear-wood sections between whorls make good shingles. Probably the only drawback to white pine is that if the timber is cut and worked during the growing season, pitch oozing out of the sapwood can be annoying. Considering all factors, this wood has to rate as one of the best timber-framing species. If I was limited to only one wood for all parts of a house (frame, floors, windows, and so on), eastern white pine would be my choice.

Second-growth white pine timber is readily available in the longer lengths.

Hickories, Carya genus: This family contains the strongest and heaviest of commercially available woods in the United States. Though hickories are usable for timbers, boxed-heart timbers are prone to very fast end checking and splitting. I have heard stories from loggers about cutting a tree into logs and, while the men ate their lunches, the logs split themselves neatly in half. It might be wise to use halved sections rather than boxed hearts.

Maples, Acer genus: Red maples and sugar maples are very common in much of New England, and both are usable for timbers if worked green. The maples have a fairly high rate of shrinkage. In addition, watch out for spiral grain, which is common. They have no rot resistance.

Northern Red Oak, Quercus rubra: A strong, heavy timber with a red to pinkish heartwood. Red oak grows faster than white oak and often has trunks clear of branches. It has a moderate rate of shrinkage and works nicely. Unfortunately, red oak is not resistant to decay like white oak. Because of its color and strength, it is one of the most-used species in contemporary timber-framed houses. However, at the current rate of usage, the supply in the Northeast may be exhausted soon.

Quaking Aspen, Populus tremuloides: Quaking aspen is similar to bigtooth aspen but less desirable. It usually grows less straight and has more branches. The wood is creamy white with brown- or green-tinted heartwood. Unfortunately, the heartwood is often rotted on the larger trees of usable size. It is not decay resistant.

Red Spruce, Picea rubens: This is one of the main timber trees in the forest that stretches across northern New England. Old-growth specimens are occasionally four hundred years old with extremely small growth rings. Red spruce was often used in houses for timbers, planking, flooring, lath, siding, and shingles in those regions where it is common. It is light in weight even when green but is very stiff. Red spruces typically grow straight with numerous but small branches and little taper in the trunk. The wood is slightly harder to work than white pine. The knots, however, are extremely hard and sometimes they shatter when struck with a chisel. On rare occasions, the steel in the chisel shatters! Spruce is not decay resistant and has more than its share of spiral grain. It is especially useful for long, straight timbers and poles.

Sassafras, Sassafras albidum: This aromatic wood works well and is very rot resistant. The wood makes fine sill timbers for this design if trees are available in sufficient size.

Tamarack, Larix laricina: Also called eastern larch, this deciduous evergreen often grows in wet areas but is modest in size. It is workable and fairly rot resistant. The lower portion was often harvested for ship’s knees by excavating to expose the roots. An elbowed section was then cut from the trunk and a major root.

Tuliptree, Liriodendron tulipifera: Also known as yellow poplar, this fast growing and often straight and tall tree is very useful. Trunks clear of branches for 60 or 80 feet are not uncommon. Its light, even-grained wood is easy to work and stable. Like white pine, it has a multitude of uses and can be substituted for white pine in this frame.

White Ash, Fraxinus americana: This straight-growing hardwood has strong, creamy white wood with occasional brown heartwood. Though straight, knot-free specimens are common, white ash is a little harder to work than it appears. It often develops large checks, but white ash is still a usable timber tree.

White Birch, Betula papyrifera: This is a pioneer species and thus is not long lived in the forest. Though it doesn’t reach impressive size, it is often big enough for all but the longest timbers. It works nicely with hand tools.

White Oak, Quercus alba: White oak was the wood of choice in those areas where it was common. It is heavy, strong, and very resistant to decay. Its shrinkage rate is very high, and it is more difficult to work than red oak or beech. Because of its durability, white oak is the best choice for sills and frames exposed to the weather. Its gradual but pronounced swelling at its butt is useful for jowled posts.

Yellow Birch, Betula alleghaniensis: Old framers used yellow birch sporadically in the northern hardwood region. Its golden birch bark is a familiar sight in mature forests. It is very strong but somewhat hard to work. Its wonderful winter-green aroma makes up for any of its shortcomings.

Timber is likely to have all sorts of characteristics (usually called defects) that affect the wood’s workability, appearance, and/or strength. Most of these are inherent in a living material such as wood. As woodworkers and timber framers, we must learn to work with these characteristics. What follows are a few of the more common traits of wood you need to understand.

Green timber is saturated with water, and wood inevitably shrinks as it dries. Why not use seasoned wood, which is largely “preshrunk”? The craft of timber framing has evolved to accommodate all of wood’s characteristics, including shrinkage. Green timber is much easier to work. Historically, with the exception of certain stock items, timbers were custom hewn or sawn for a job and used green. If traditional joints are used and the peg holes drawpinned, the joints will be reasonably tight after the timbers have shrunk.

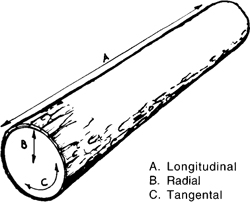

However, you still need to understand shrinkage. To predict how wood behaves as it dries, we must first understand the three types of shrinkage in wood: longitudinal, radial, and tangential. Longitudinal shrinkage is quite small and not really a concern. A 20-foot timber might shrink ¼ inch. Timbers with excessive reaction wood or crossgrain are more likely to shrink in length and should be avoided where such shrinkage might cause a problem.

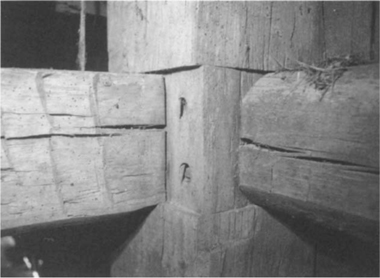

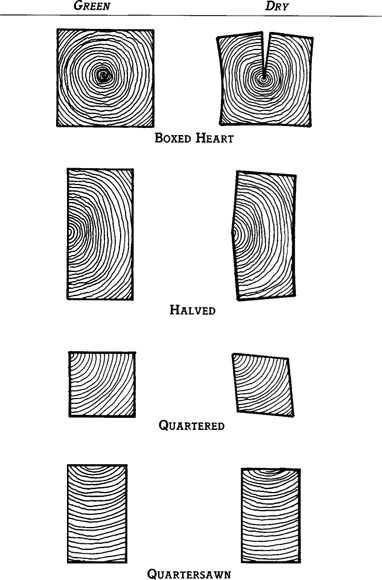

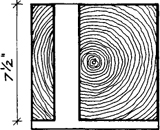

Radial and tangential shrinkage produce distortion and reduction in cross section, and their effects depend on how the timber was sawn from the log. In boxed-heart timbers, tangential shrinkage is responsible for most of the checking. But the combination of radial and tangential shrinkage causes the faces of the timber to warp. The face that receives the biggest check is usually the face closest to the heart, but a mortise or row of mortises can also stimulate a check. In boxed-heart timbers, checks are unavoidable. In timbers halved from the log, checking is reduced but the faces still distort. On the halved face, the center might be ¾ inch higher than the edges on a 12-inch wide hardwood member. In quartered timbers, checking is minimal but the square cross section becomes a diamond shape. In quartersawn timbers, both checking and distortion are minimal. Quartersawing is only practical with small timbers or very large logs. This is the preferred sawing method for furniture and flooring stock but hardly practical or necessary for a timber frame.

THE TYPES OF SHRINKAGE

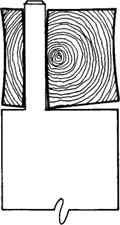

We must take shrinkage and distortion into account as we fashion the joinery. Traditional techniques such as draw-pinning (also called drawboring) joints compensate for them: Offset peg holes put a bend in the peg that acts like a spring to keep the joint tight as it dries.

Another technique balances the relative shrinkage rates of mortises and tenons. Tenons must be cut shorter than their mortises are deep because mortise depth diminishes as the timber dries but the longitudinal grain of the tenon does not. On through-tenons, cut the tenons an additional ⅛ or ¼ inch shorter so as not to push out the exterior sheathing as the mortise shrinks in depth. In addition, the inside surfaces of scarf joints and housings must be hollowed out to allow the joint to remain tight as they dry.

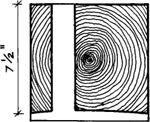

This end grain from an 8-inch by 10-inch pine timber was cut to the pith to demonstrate how tangential shrinkage can distort boxed-heart timber.

Though you cannot prevent shrinkage, there are ways to minimize its worst effects: Use winter-cut timber, so that it will begin to dry slowly before the hot weather comes. Stack timbers out of doors and in the shade. If you are using hardwood timbers and must stack them in the sun, use a commercial end sealer to prevent too rapid drying. Cut your joints in the timber soon after it is sawn out — mortises and peg holes allow the moisture from the inner part of the timber to escape nearly as fast as the surface. The worst checks occur when the outer surface dries while the interior is still saturated.

If the frame is raised in the spring or early summer and covered with a roof, the timbers will continue to dry slowly. Once cold weather begins and the house is artificially heated, however, the frame will begin to dry out rapidly and you may even hear some cracking noises. In fact, you could actually see cracks opening while you watch. In time, the frame reaches a general equilibrium with the atmosphere, although changes in the humidity will cause some expansion and contraction in the wood indefinitely.

Oiling or finishing the timbers will not prevent checking and may actually worsen it. If you do wish to apply an oil finish, allow the frame to season first.

As long as trees grow with branches, knots are inevitable. On forest-grown trees, the lower branches die and rot off while the tree is still thin. As the trunk thickens, clear wood is added over these branch stubs. Timbers sawn from such trees may have a surface clear of knots and only small knots buried within. When a tree grows in more sunlight, lower branches continue to get light and grow and thicken. Some species such as ash lose branches easily and have clear trunks. Species like spruce may keep their dead branches for the life of the tree. When sawn into boards, dead branches create dead, loose knots that may fall out.

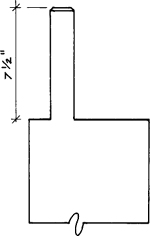

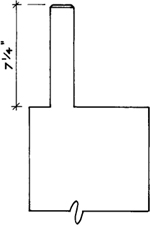

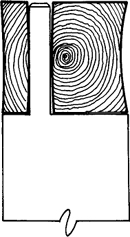

The effects of shrinkage on joinery: A through-tenon cut to the same length as the mortise depth or a housing that is not hollowed out will cause problems as the timber shrinks.

If the tenon is cut a little shy of the mortise depth and the housing is scooped out, then the joint will remain tight as it dries.

Because the grain changes direction at knots, the timber is weakened and the wood is harder to work. During layout, avoid placing joinery at knot locations. In addition, avoid timbers with knots larger than one-third the width of the timber. On certain species, the knots can also be a dominant visual feature.

When a leaning or a curved tree is sawn into timbers, the release of stresses during the cutting is likely to produce a bow in the timber. Likewise, when a straight log is cut down the middle, the ends of the two halves typically bow away from each other, and when a log is quartered to produce four timbers, each will have a bow in two directions. If the timbers are oriented correctly, bows are acceptable for spanning members because the loads tend to straighten them. For posts, plates, and other members where straightness is important, however, use boxed-heart timbers sawn from straight, nonleaning trees.

When a crooked, crotched, or curved log is sawn into a straight beam, at least some of the wood fibers will not be parallel with the beam’s edges. Since the fibers are not continuous throughout the timber, it is weakened. Nonparallel fibers are called crossgrain. The checks of a dry crossgrained timber are also not parallel to the beams, and the amount they vary from parallel is referred to as the slope of the grain. Some crossgrain is permitted in graded lumber — a slope of up to 1-in-11 in #1 timbers and l-in-6 in #2 timbers. You can measure the slope yourself, however. A l-in-6 slope, for instance, will run 1 inch closer to the edge for every 6 inches of length. Do not use timbers with slopes of more than l-in-6 for structural applications.

Occasionally, trees spiral like a corkscrew as they grow. Some attribute the spiral to the effects of the wind, while others feel the twisting has more to do with the magnetic fields of the earth’s crust. Regardless of its cause, spiral grain can definitely affect your timber selection. In The Craft of Log Building (1982), Hermann Phleps writes:

There are two kinds of spiral twist, one of which is acceptable for building purposes, while the other may produce major distortions with potential for structural problems. If the twist runs counter to the sun (i.e., right hand), the old-time dictum of the Bavarian carpenter was that this wood would retain its shape when felled. If it runs with the sun, however (i.e., left hand), the bundles of fibres attempt to twist back during drying and in the dried state. This process, which may go on for years, is so powerful that it may force log walls out of plumb and loosen or even force apart roof framing.

Whenever I have seen a contorted, twisted timber in old or new work, the checking will invariably indicate a left-hand spiral relative to the tree’s growth as Phleps predicted. Compare the tree’s or timber’s spiraling grain to a screw thread: A normal screw thread has a right-hand spiral. If you cut your own trees, you can usually spot spiral grain in the bark. Regardless of the spiral direction, however, if the grain spirals more than about 1-in-ll, avoid that tree or timber (see the section on crossgrain to determine the slope of the spiral actually present).

Shakes are separations between the annular rings and they weaken timber. They are believed to be caused by wind. A single shake in a boxed-heart timber might not be a problem, but many shakes can cause the timber to act like a loose bundle of shingles. Joints cut in shaky wood will cause the timber to literally fall apart. These timbers are to be avoided.

When a tree leans, curves, or has heavy branching on one side, reaction wood develops to compensate. In softwoods, this reaction wood often appears darker and is brittle to work. If you are chopping white pine and the wood shatters rather than splits, it probably has reaction wood. In hardwoods, reaction wood has a silken appearance and gives the surface of a sawn piece a fuzzy texture. I once tried to square up the end of an 8×8 basswood timber with a variety of hand saws without success. None of the saws would penetrate more than an inch before the fuzz stopped them. Even the chain saw that cut the log in the woods had a hard time of it. This timber had been cut from a leaning tree.

Right-hand spiral grain is evident on this smooth old beech tree.

Extreme reaction wood is evident in the end of this crooked pine log. Note the dark growth rings and the off-center pith.

Because reaction wood shrinks more longitudinally than otherwise, it can cause warpage problems. Avoid abundant reaction wood for spanning members or where it might weaken critical joints. A good use for timbers with reaction wood might be stocky members such as an 8×8 post that is only 8 feet long and carries modest vertical loads.

I like to refer to wane as nature’s chamfer. To minimize waste, sawyers and hewers try to use the smallest log that is practical to get the required timber, which often gives waney edges. In Europe, waney timbers are common in old frames because timber was scarce and could not be wasted. Wide decorative chamfers and molded edges found in more formal framing may have been the best way to disguise the inevitable waney edges. Wane is really a matter of taste. Today, some see wane as an undesirable imperfection. Others prefer wane as the timber still looks a bit like the tree from which it came. I feel that the rounded corners make the timber frame a bit softer and friendlier.

Always remove the bark from waney edges as it holds the moisture that attracts insects and fungi.

You needn’t worry about wane reducing the strength of the timbers — the system of commercial grading of timbers includes allowances for wane. In Select Structural grade (posts and timbers), wane up to ⅛ of any face is permitted. In #1 grade, one-quarter of any face, and in #2 grade, one-third of any face, is allowed. Thus, in a #1 grade 8×8 timber, the wane may reduce a face down to 6 inches.

Remove the bark from the wane and smooth any rough spots with a spoke-shave or drawknife. In freshly cut wood, the bark is easily removed and the surface below is silky smooth.

If you look on a freshly cut stump or on the end of a log, you will see in most species a band of lighter colored wood just below the bark. This is the sapwood, the living part of the tree involved with the tree’s food storage and production. On open-grown full-crowned trees, most of the wood is sapwood. On forest-grown, narrowcrowned trees, however, the sap-wood may only be an inch or so wide. On virgin-growth timber, it is so narrow as to be insignificant. During the growing season, most softwoods ooze sticky sap out of the sapwood band immediately after cutting. Sapwood is also prone to fast staining from fungi and insect attack if cut during the growing season.

Beneath the sapwood lies the heartwood, which is not living. It usually seasons better than sapwood and the extractives in its cells usually make heart-wood more durable. In many species, it is also more colorful.

Of all the characteristic differences between heartwood and sapwood, the most important for building purposes must surely be durability. Assume that you cut two boards from the same white pine log so that one was made entirely of heart-wood, the other was made entirely of sap-wood, and that you installed them both on a house exterior. You would quickly see that they perform quite differently. The heartwood board might last three hundred years and would wear away (about ¼ inch a century) rather than decay. The sap-wood board would be attacked by fungi almost immediately and might need replacing in five years. You may be surprised to know that many commercially made wood items such as windows, doors, trim, and even wood shingles are sold with abundant sapwood in them. If more people in the wood industry knew or cared about this important difference between heart-wood and sapwood, we would need a lot fewer chemical preservatives.

The upper log, a red oak, has sapwood that was stained by fungi. The lower log, a white pine, has oozing sap that crystallized.

Unfortunately, today forests are managed for fast production. Fast-growing healthy trees have a lot of sapwood, and the wood from these fast-growing trees will not last very long! Slower-grown trees might be more economical in the long run if we consider the wood’s durability in evaluating the price.

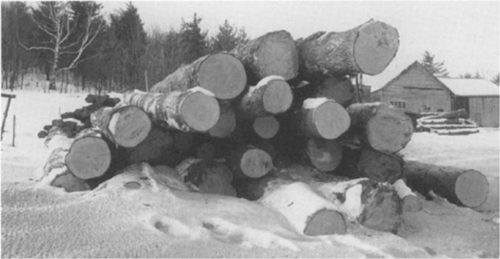

Traditionally, many farmers became loggers in winter to provide timber for new farm buildings. In many areas this tradition continues.

In the past, when a farmer decided to build a barn, he went into his woods in winter, felled the necessary trees, and dragged them out of the woods. He might have taken some logs to the local water-powered sawmill for boards and planks when the spring thaw came, but he would hew the rest of the logs into timbers for the barn frame. The owner played an active role in timber procurement. Today many people in this country are so far removed from natural systems that they don’t even seem to understand that wood comes from trees. They certainly don’t realize that they can produce timbers from their own trees. In fact, there seems to be a tendency to believe that anything from nature must somehow be processed by industry to make it safe for us to use. The opposite is too often true: Industry often takes natural things that are safe and makes them unhealthy for us.

If you cut and build with your own timber, you and your part of the world will be a little better off. If you have land or access to land with suitable timber, you could use the timber for all parts of the house. Even the wood for floors, doors, trim, siding, and counters can be taken from your own trees if you store and season them properly. Kiln-dried lumber and air-dried lumber only differ by production time and cost. If you plan ahead, your lumber will be properly seasoned when you need it and you will have saved the cost and tremendous amount of energy necessary to dry the lumber quickly in the kiln.

In fact, you could become a combination forester/logger/sawyer, invest in all the necessary equipment for each role, and do everything yourself. Many owner-builders have done that and learned a great deal in the process. If you are naturally inclined toward work in the woods, it may be the route for you. There are good texts out there that cover timber selection and harvesting (see Further Reading). Portable sawmills range from simple, inexpensive models up to more expensive production models (see Appendix B) that allow you to saw timbers, boards, clapboards, and even shingles.

However, if you don’t have all that time or don’t want to invest in a lot of equipment, you can minimize your investment and still be personally involved in the process. You can select and cut the trees and then hire someone to pull the logs to a central area for hewing or sawing. The selection, felling, and dragging are best done in the winter when the ground is frozen or snow covered to minimize damage to the woods and keep dirt and stones from being embedded in the bark of the logs. You could hire a logger with a rubber-tired skidder or a dozer to drag the logs out but there is likely to be more damage to your forest, and if many trees are scarred in the process, there may not be suitable timber later on. (This may not be a factor if the trees are all cut where the future building site will be.) On the other hand, you could hire a local horse logger or a farmer with draft horses or oxen to do the dragging. Regardless, now that you have the logs felled and located together, you must now decide if you will hew or mill them into timbers.

This phase should quickly follow the logging, preferably before warm weather arrives because logs stacked over the summer will be attacked by sap stain fungi and wood-destroying insects. Logs may be stored underwater in a pond if convenient. In fact, underwater storage can be very beneficial. When logs are stored in water, the sap slowly diffuses out and is replaced by water. When the logs are taken out, they will dry faster and be more resistant to decay and attack from fungi and wood-boring insects.

You have several options for the sawing of your lumber. If you don’t consider labor, the least-expensive method is hand ripsawing over a pit or on a trestle. The process goes faster than you might think. With two people in good shape and a proper setup, hand ripsawing could compete with some portable mills. As late as the 1930s, local wood was still sawn by hand in parts of the British Isles (see Linnard [1981-82]). In fact, some parts of the world still ripsaw by hand and the large saws are still manufactured (see Appendix B). The log is secured on the trestle or over a pit. Lines representing the cutting planes are snapped on the surface, although sometimes in the past the log was first hewn square for convenience and then sawn. Some surviving seventeenth-century houses have timbers with two hewn faces and two sawn faces, indicating that a hewn timber was sawn into quarters.

Inevitably, more people will choose a portable sawmill over a hand ripsaw. If you are buying a portable sawmill, consider how much timber you’ll be cutting. The least-expensive mills might do just fine for just a few timbers. If you plan to be cutting everything for the house, consider the larger and more automated models. If you plan to do custom milling for hire, get a trailer-mounted mill. Make sure the mill’s cutting capacity, volume, diameter, length, and other vital statistics are appropriate for your needs. Remember that by moving the cant (the log being sawed) on the frame or carriage, you may be able to saw logs a few feet longer than the mill’s stated capacity. However, if you will need a lot of longer pieces, get a mill with the longer capacity.

Some portable sawmills are small enough to go to the log. For just a few timbers or for timber that is relatively inaccessible, this might be the type of mill for you.

There are a lot of portable sawmills already out there that may be available (with operator) for hire. If the logs are stacked and ready for milling, a few days with a good portable sawmill should produce all your lumber. The leftover slabs can be stacked for firewood and the sawdust used for mulch in your garden. And you will still have involved yourself in the production of your house’s lumber in addition to contributing to the local economy.

▾You can set up a portable sawmill on your land and build your house from your own trees.

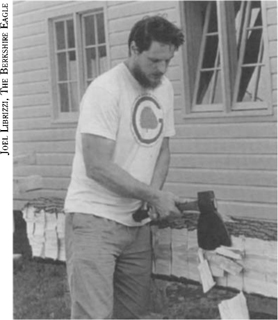

Hand hewing is a low-tech approach that is, in some circumstances, still viable. With a minimal investment in tools, logs are turned into beautifully textured timbers.

A good working height allows you to work without being bent over.

The craft of squaring up a log with an ax has been with us since ancient times. Most pre-Industrial Revolution structures in this country have at least some hewn timbers. In predominantly sawntimber structures, the longest members were hewn since they were too long for the sawmill. Hewing is hard work but it can be economically feasible if you become adept at it. The first timbers that I squared up were rough and the work was very tiring. As I developed skill and got the right ax, the work became less tiring and more rhythmic and satisfying. With good logs, hewing may be the most economical source of long, square timbers.

Getting Started Hewing. To hew your own timbers, you will need decent logs, the right tools, and plenty of time. The logs should be relatively straight with mostly small knots. Knots consume time and energy. Clear, perfect logs should be saved for other, more-appropriate uses, such as furniture and flooring. Logs with mostly large knots — 3 inches in diameter or more (and 2 inches in diameter or more for spruce) — should be set aside for planks or boards. As stated previously, logs with excessive spiral grain are tricky to hew without tearing the grain. Dry logs are also much harder to hew, so try to hew a log soon after felling it. It isn’t necessary to peel the bark, but if you do remove the bark, allow the log surface to dry out before hewing. Because you stand on the log for part of the process, remember that a wet, slippery log can be dangerous.

The hewing area should be on relatively level ground, free of brush, low branches, or saplings that might deflect the ax. Hew the log where you felled it if that is more convenient. The chips generated from the process are a potential fuel source and a good compost for the forest.

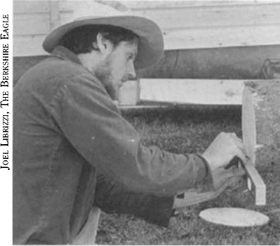

The logs shouldn’t be hewn on the ground. Elevate them on either cross logs or on horses. The ideal log height allows you to hew with a broadax either toward or away from you. The center of the log should be somewhere between 20 and 30 inches off the ground. If the log is too low, your back may be strained. If it is too high, you can only hew away from you. Remember as well that as the chips accumulate on the ground, the relative height of the log to you will diminish, so you may need to adjust the log. My hewing saw-horses are based on medieval illustrations. They allow a log to be rolled up onto them, and notches keep the log from rolling off. Whatever kind of log support you use, set up your work area so that there is a minimum of handling of both logs and timbers. Ideally, the hewing area should be between the log pile and the beam pile. You can then move finished beams off the hewing horses, one end at a time, to the beam pile.

Tools and Equipment. For moving logs you will need a peavy, which is a log rolling tool. Better yet, get two peavies if you have help available. One person can then hold the log while the other person gets a new grip on the log. The spiked point of one peavy can also be driven into the ground or another log and the log rolled in place against it by the other person with a peavy. A 4- or 5-foot long pry bar may also be helpful for moving logs. If you have a helper, you can move a log with a timber carrier, which is basically two peavies joined together. In fact, you can substitute two peavies for a timber carrier. With a timber carrier, you can lift one end of a large log to set it up on saw-horses, or you could drag a smaller log out of the woods. With four people and two timber carriers, logs can be carried clear of the ground.

In addition to being held in the notch, logs need to be fastened to the hewing sawhorses or support logs to prevent shifting. Forged iron dogs were used in the past. An iron dog resembles a giant staple with one end driven into the log and the other into its supports. These can be purchased or you can substitute scraps of wood with spikes.

These hewing trestles, based on early illustrations, utilize curved slabs to roll the logs up to a good working height.

A timber carrier (top) and peavy.

The process of hewing requires two axes: a felling ax for scoring and a broadax for the actual hewing. Felling axes are available at many hardware stores. Yours should have a comfortably long handle and a head weighing at least 3½ pounds. Because this tool will also be used in roughing out joinery, more information is warranted for its selection. First, it is important that the head be properly aligned with the handle. Holding the head, sight down the cutting edge. The plane formed by the cutting edge should lie within the handle. If not, pick up another ax. The handle should also not be greatly reduced where it enters the eye of the head. The handle should gracefully taper to a thin flexible middle and then swell again at the end to a comfortable “fawn’s foot.” The fawn’s foot should be swelled in two directions. It may surprise you that the thinner handles actually last longer than the thick, rigid ones. An overly thick handle will not absorb shocks well and eventually the handle will snap where it enters the eye. A rigid handle also transfers the shock to your hands and shortens your hewing years considerably. If the handle is varnished, use some rough sandpaper to remove the finish. You get less blisters with an unfinished handle. The cutting edge should be curved, not straight. A curved edge sinks deeper into the wood with less shock to your hands. The edge should be sharpened to about a 30-degree angle, though this is easy enough to change. The steel at the cutting edge should be soft enough to sharpen easily with a file. You want the edge to dent rather than chip. The thickness of the blade next to the bevel should be about ¼ inch. If the ax is too thin here, it will stick in the wood and require working it back-and-forth after each stroke. An ax of the proper thickness pops the chips off.

The poor imitation of a fawn’s foot on left is cut from thin stock and is uncomfortable to use. The handle on the right is well made from thick stock.

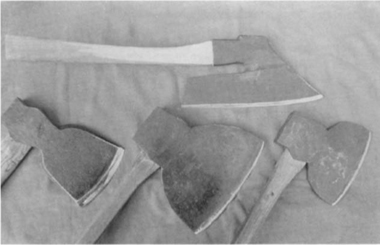

Some right-hand broadaxes (clockwise from top): Germanic “goosewing” type with 12-inch cutting edge, early nineteenth century; American ax with 7-inch edge; late nineteenth-century ax with 9½-inch edge; and a new “Kent-style” ax from Woodcraft Supply.

The broadax does the final shaping with short, controlled swings. If you will be working mostly hardwood logs, choose a broadax with a 6- to 9-inch cutting edge. Cutting edges of 9 to 14 inches are for softwoods. The wider the edge, the more wood you will be pushing through. Because the head’s weight helps push the ax, a head with a 6-inch cutting edge should weigh about 5 pounds, with the wider-edge axes weighing considerably more.

Broadaxes are typically sharpened on one side like a chisel, but the nonbeveled side should not be flat. A gentle sweep is better, allowing you to control the depth of your cut. You may find some old broadaxes sharpened on both sides like a felling ax, but they are still perfectly usable. Angle the ax head away from the surface until the edge begins to cut. If the number of surviving old axes is any indication, these “double bevel” broadaxes must have been very popular. They probably served as both a scoring and hewing ax and, as a hewing ax, could be used for right- and left-hand hewing.

The cutting edge itself should not be straight or flat. As with the felling ax, a curved edge makes hewing easier. The middle of the cutting edge should cut at least ½-inch ahead of the ends. The back should also have a curve pronounced enough so that if laid on a flat surface the ax should rock. This curve keeps the corners from digging in to the work and makes the ax a sort of gouge. The smooth, scooped-out surfaces that I used to think were worked with an adz were actually cut with a broadax.

When I first began hewing, I tried those big (12-inch edge) broadaxes with straight, flat edges. Avoid them if you can. The work was very tiring and the results were rough. Fortunately, these axes can be reworked to the above specifications.

Broadax handles are typically much shorter than felling ax handles. The length including the eye should be from 16 to 24 inches. Note that the handle is offset away from the flatter face of the ax to provide clearance for your fingers. If laid on a flat surface, the end of the handle should be at least 3 inches off the surface. Since many old ax heads lack a usable handle, you will probably have to make one. Your handle can be angled where it enters the eye or curved along its length. Use wood with a natural curve rather than steambending a straight piece — I steambent a handle in 1976 that straightened itself out after a few years. Most knot-free hardwoods are fine for broadax handles. Many broadax heads can be hung for either right-or left-hand use. If you are right handed, your right hand is closest to the head and the log is on your left. On some axes, such as “goosewing” types, the eye itself is offset and you don’t have a choice.

Once you have a broadax with a handle, you need to sharpen it. To sharpen the broadax, first hone the back to remove any pits near the cutting edge. Remember, the back should be slightly rounded. Hone the back until it is virtually a mirror finish for the first ¼ inch or so. Then the bevel should be filed (the steel may be too hard for filing) or hand stoned to a 25- to 30-degree bevel. With a fine stone, the bevel is next honed at a slightly steeper angle. Broadaxes need to be kept very sharp for good results. Protect the edge during storage with a sheath. A knick takes a lot of time to fix.

You also need a 2-foot long level, a pencil, a chalkline with blue or white chalk, an awl or nails to hold the chalk-line, and safety goggles or glasses. You may need a drawknife to peel off any strips of rough or loose bark where lines are snapped.

When the log is secured, the ends are laid out using a level.

Hewing Layout. Space your hewing sawhorses with about two-thirds of the length of the log between them. Thus, on a 12-foot log, about 2 feet will project at each end. Rotate the log in its cradle to its best advantage. Peter Gott, a log-building specialist, recommends putting the crown (see Glossary) down so sighting down the log is easier. Then, drive in the iron dogs with a sledge hammer — not your ax — or nail on some 2×2s with staging nails.

Now you can lay out the log’s ends with the proposed timber size. By using a level to draw lines on the ends, the hewn timber will be free of wind. Unless the log is perfectly straight, the timber layout will not be centered in the log’s end. You may have to compensate for bows or swells by moving the end layout off-center. Use your judgment to locate the timber roughly in the center of the entire log. This process takes balance, but after some practice you will soon lay out the dimensions with confidence. Don’t worry about having some waney edges left. Draw all lines out to the bark and also draw a vertical centerline, which aids in joinery layout.

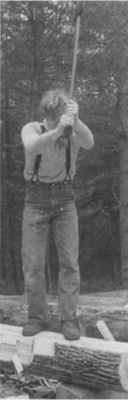

Scoring is best done while standing on the log. Make vertical scoring cuts to the line every 4 to 6 inches.

The vertical face opposite the dogs will be hewn first. Before snapping your first chalkline, remove any branch stubs, loose bark, or other obstructions that might deflect the line. You can snap a good line on smoother barks, but rough barks require that you peel a narrow strip of bark away from where the line will be. Don’t peel any more than necessary or the surface will be too slippery to stand on. Using the ax or a knife, make a slit in the end of the log where the vertical line meets the edge to keep the chalkline from sliding down. Use a nail or awl to hold the end of the line. Stretch it out above the length of the log, lightly snap off the loose chalk, and then lay it on the log in the other slit. Stretch it tight. Now, pull the line directly vertical (plumb) and let it snap. If there are hollows, it may be necessary to repeat the process for just those portions that were missed. You have now described the vertical hewing plane.

Though there are many ways to hew a log, evidence indicates that the standard way to hew in the past was to work on vertical faces. When all criteria is considered, it seems like the best approach.

Scoring. The scoring process uses a felling ax to remove the bulk of the waste wood and prepare the log faces for the broadax. On small logs and areas where the wood to be removed is only a couple of inches thick, make scoring cuts to the chalkline about every 4 to 6 inches. Stand on the log with your feet spread apart and your toes safely behind the chalkline. Steel-toed shoes are a good idea here. Start at the butt (the bottom of the tree) of the log and work up to the tip. The felling ax should enter the log at roughly a 45-degree angle and point towards the butt. An ax of the proper thickness will pop the chips off; a thinner ax will require that you gently pry them off using the handle. At knots or bulges in the log, you have to work from the opposite side to keep the chips splitting away from the line. You will quickly learn the best angles and direction to be the most effective. An advantage to scoring this way is that the chips rarely fly up at you, though I still recommend safety glasses; the hard, brittle wood of knots can shatter.

Except at the ends, you will be guided by only one line because there is no line on the bottom. Use your eye to gauge plumb scoring. You might also check your work occasionally with a plumb bob or level to keep it roughly vertical. The depth of scoring is important. If you score too deep, the finished piece will be missing some wood. If not deep enough, the broadax work will be tedious. Perfect scoring makes the broadax work easy and leaves evenly spaced shallow cuts in the finished timber.

Juggling. When more than a couple of inches of wood must be removed, use a time- and effort-saving approach called juggling. Cut a V-notch with the felling ax to the chalkline at intervals of 1 to 2 feet. Locate these notches at the knots if practical. Then split these sections off, starting at the tip end and working down the log. With the large sections removed, rescore the surface every 4 to 6 inches as above.

Juggling works best on the straighter logs. On wavy logs take care to prevent splits from running into your line. Because of their natural taper, most logs only need juggling near the butt end.

On larger logs, juggling will remove the bulk of the wood quickly. Notches are cut to the line and the chunks in between are split off.

With practice, you can work to the line with a minimum of strokes.

After splitting off the juggles, rescore the remaining wood to the line. Now the log is ready for the broadax.

Hewing. Now that the log’s fibers are scored roughly to the finished plane, you are ready for the broadax. You scored up the log, now you hew down the log. Starting at the tip, slice away the wood to create a plumb face that splits the chalkline. If you are right handed, the log is to your left. If you are left handed, the log is to your right. Depending on which way the log is lying and whether you are right- or left-handed, you may face the butt or the tip. I prefer to hew backing up (facing the tip). Unless the logs are all stacked with butts at the same end, you may have to work both ways.

Using the broadax requires some practice, but it rarely needs hard swinging. Since it is heavy, let its weight push it through the wood. Your right hand (if you are right handed) should be closest to the head and does most of the work. Use short, controlled strokes. Without control, you risk slicing into your leg. Again, steel-toed shoes are a good idea. The broadax should be angled toward you if you are working backward, and angled away from you if you are working forward. The combination of the swing and the angle on the ax creates a slicing action that removes wood easily with little tearing of grain. At knots and changes in grain direction, change the angle of approach to minimize tearing.

Starting at the tip end, hew the face plumb and to the line. Position your sighting eye directly above the line.

Again, try to split the chalkline as you hew. Check the verticality of the face occasionally with a level or plumb bob. If you follow the line and keep your face plumb, the surface will be amazingly flat.

When finished with the first face, loosen the dogs and turn that face up. Rotate the log until the centerline is exactly level and refasten the log. Then snap a chalkline for the second face. Remember to pull the line up plumb to snap it. Since this line is on a flattened face, it should be clear and easy to follow. Repeat the scoring and hewing process until the log is completely squared.

Depending on your setup, you may be able to score and hew both vertical faces before turning the log. You will have to move the dogs, however. On long logs, the log may bow if you remove wood from only one side. If you then snap straight lines on a slightly bowed log, you can end up with a timber that is somewhat thicker in the middle than at the ends. If you are hewing long logs (over 16 feet), snap a line for each vertical face and hew both before rotating.

Hewing Variations. Some prefer to stand on the ground while scoring and work the top surface. Some turn the surface to be hewed at roughly a 45-degree angle. In these cases, two chalklines are necessary. I have found that I receive a lot of chips in the face with these methods, so wear eye or face protection if you try them. Unfortunately, the lines should be snapped in the vertical position before the log is turned and scored. Afterward, you must again turn it back vertically for the broadax. This is extra handling. The advantages to these variations are that when you are scoring, you are standing straight rather than bending over, and that your feet are in a less dangerous position. Some hewers like to use a long, straight-handled broadax and stand on the log to hew the vertical face. This method seems to have less control.

This 10-inch by 13-inch white pine timber measures 32 feet long and took 14 hours to hew.

Regardless of your hewing method, scoring with a chain saw can be a shortcut if the logs are oversized. But you should stay at least an inch or so away from the line. Juggle the big chunks off and rescore with the ax. Remember, it is the scoring marks from the ax — not the marks of a chain saw — that give a timber its distinctive hewn look.

Adzing. I used to think that the smoother hewn timbers were finished with the adz. In fact, I’ve adzed quite a few timbers in the past. But if one examines old hewn timbers carefully, the evidence shows that the smooth, scooped cuts were done with a broadax. The tool marks show that a cutting edge was used in a slicing motion, which is nearly an impossible feat with an adz. I believe the adz was used in house construction for tasks such as leveling high spots in floor joists, shaping joist and rafter ends to fit their notches, adjusting the thickness of flooring when it ran over joists, and scarfing clapboards when they lapped, and I believe that the adz still has a place for all of those tasks. But I do not believe that adzes were often used to smooth timbers.

Even odd pieces such as this five-sided ridgebeam can be hewn easily. Keep the face to be hewn vertical when that side is finished, then rotate the log to the next side.

If you choose to use commercially milled wood, you should find a good sawyer. Here in the Northeast there are many small family-run sawmills tucked away in the forested hills. Chances are good that one of them has the right logs for a project, although your part of the country may not have many mills. The smaller and less mechanized the mill, the more reasonably priced the timbers will be. Speed isn’t really a factor anyway. The larger mills aren’t necessarily faster, and if you can get just a few timbers to start with, the mill can have some time to cut up the rest. If you get all your timbers delivered first and then spend six months working them up, some will be dry and difficult to work toward the end. Getting small batches delivered periodically is a good arrangement.

Before you pick a sawyer, check out his or her work. Are the timbers fairly square, consistent in size, stacked properly to prevent staining, and free of scarring or grease stains from handling? Rough saw cuts indicate dull blades or improperly set teeth. A good sawyer takes the time to keep the mill in top running condition. Don’t be fooled by the rough structures that usually house sawmills — a finely tuned machine may lie within.

Small local sawmills can offer quality timber at a reasonable price. Don’t be fooled by the rough structures that usually house them — a finely tuned machine may lie within.

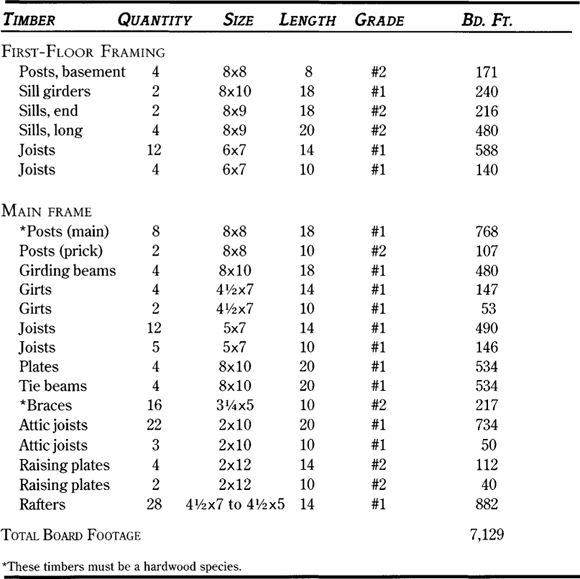

Ordering. The two-story (18 foot) posts and the braces should be a hardwood species. In the Northeast, oak, maple, beech, birch, hickory, ash, black cherry, and locust are all suitable. All other timbers can be eastern white pine or a stronger species. See the Wood Handbook (USDA 1974) for a comparison of strengths. To the left is the list of timbers you will need for the project house.

The list includes exactly the number of pieces required. However, you probably need to order additional pieces in case of mistakes or defective timbers.

When you give the sawyer the lumber list, take some time to describe what kind of timber you expect. If you give a range of species to choose from, the sawyer’s work will be easier and faster. Otherwise, the mill might have to wait until a logger brings in enough of the particular species that you desire. Tell the sawyer how much wane you’ll accept, what size knots are permitted, and how much spiral grain or crossgrain you will accept. Talk about preventing sap stain, how the timbers are handled and delivered, and anything else that might affect the appearance.

The common delivery unloading method seems to be dumping. Unloading by hand does the least damage but requires much more labor. Have it dumped next to your stacking area so that you can move logs one end at a time to your timber pile.

The timber should be stacked the same or next day if possible. Elevate the base for each pile at least a foot or so off the ground to provide for air movement below and allow a lawnmower underneath to keep vegetation from growing up through the pile. Provide cross supports every 6 or 8 feet on center to prevent the timbers from sagging. Sight down the supports to make sure they all lie in the same plane. A pile that slopes lengthwise a few inches is good, so that if rain gets in, it will run off.

Using short 2×4s, seventeen people carried this 40-foot long barn timber easily.

All pieces in a layer should be spaced at least 1 inch apart with at least 2 inches between layers. The stickers (spacers between layers) should be 2×2s or larger, of dry stock, and positioned above the supports. The brace stock can be used for stickers if necessary. Only cover the top of the pile, using old sheet metal roofing, lapped plywood sheets, or tarps to keep out the rain and sun but still allow free air movement. A shady location for storage and working is recommended.

This timber transport was made from two trailer wheels and allows one person to move large timbers on fairly level ground. Place each timber so that its midpoint or balance point is centered on the transport.

The ideal working area is parallel with and lying between the rough and finished piles. This means that one person can move a timber one end at a time from the stockpile to the sawhorses and then to the finished stack.

If timbers have to be moved, there are a number of ways to do it without hurting yourself. Avail yourself of others that can help. With many people helping, you can use 4-foot long 2×4s, pipes, or bars that can be slipped under the timber. Then pairs of people can lift and carry the timber comfortably. Timbers can also be rolled on 3- or 4-inch PVC pipe or wooden rollers. A plank roadway can be set up on sawhorses to roll them on. A more mobile solution is to make a two-wheeled timber carrier with rubber tires. If a timber needs to be elevated, use a lever or inclined plane. These simple machines have been with us for thousands of years, but you might not think of using them. You don’t need to strain yourself.