I chose the hall-and-parlor house for this book because its design is very flexible and easily modified. Because people’s needs differ, you will probably want to customize the design to suit your requirements. You may want to start with a smaller structure and phase in the construction, or you may want a larger house — at the start or in time. This chapter presents some of your options.

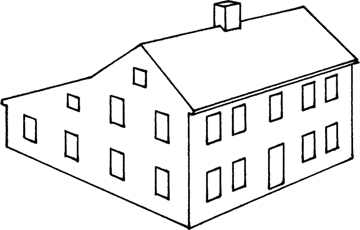

Though the hall-and-parlor house is ideal as a starter home, some may wish to start out smaller. Smaller houses are becoming more popular as the cost of building rises, and some people just don’t need much space. One option is to build a so-called half house — build the center bay with one side bay, which gives a house measuring 18 feet by 22 feet 8 inches overall. On the main level, a kitchen/dining/living room could occupy the 14-foot bay and the hearth, stairs, and entry could occupy the 8-foot bay. Above could be one large bedroom and a bath or two smaller bedrooms and a bath.

The only modification necessary to build a half-house frame is to lay out the smaller bay’s exterior wall as an exterior bent. The sill girder on the end wall can be reduced from an 8×10 to an 8×9. The plates, since they are only about 23 feet long, no longer need a scarf joint.

An 18-foot by 23-foot half house.

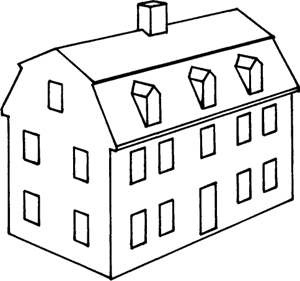

An 18-foot by 36-foot cape.

The half house can be added to later if necessary to create a “full” house. If you are planning that from the start, cut the necessary mortises for the add-on framing now. When you pour your foundation, leave some reinforcing steel bars protruding for the add-on and/or provide a vertical keyway.

You could use the full first-floor plan but only make the house one full story — a good solution for someone who doesn’t want to climb stairs. For more second-floor space, the roof could be steepened to provide space for two bedrooms under the roof, or the roof could take on a gambrel form to increase that space even more. Unfortunately, capes are not added to easily or gracefully. A lean-to with a low eave and shallow pitch is the easiest way. You might be surprised to find that many old capes were jacked up to add another story under them. If you find an old two-story house with a timber-framed second floor and roof but stud walls below, this is undoubtedly what has occurred. Kneewalls (less than full-height walls above the first floor) are relatively common in modern timber frames, but they can potentially cause structural concerns. I wouldn’t add them to this design without the advice of a structural engineer.

The ultimate shrinking of the design is to build a one-bay cape measuring 14 feet by 18 feet. This would make a great woods cabin, office, artist’s studio, or workshop. It is a great beginner project! The 8×10 sill girder now becomes an exterior 8×9 sill and, of course, no scarfs are necessary in the sills or plates. This cabin could be expanded lengthwise in the future to the full 36-foot length and become the cape. Again, allow mortises for the add-on framing.

The 18-foot width of the frame can be reduced without reengineering the design. If you find that a width of 16 feet, for example, is more appropriate, you don’t need to adjust any of the timber sizings or joints.

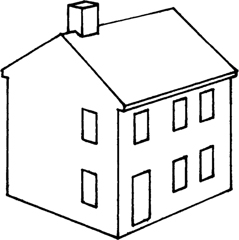

A big advantage of the hall-and-parlor house, especially the two-story version, is the ease of adding on building components that extend and compliment the house form. For starters, an ell (which is an addition off the side or at right angles to a building) could be added off the kitchen to provide an entry room, firewood storage, and/or garage. This ell might have an earthen floor with large flat stones and could be open to the south. A single-story ell with a roof ridge parallel with the main house would not obscure upper-story windows and if set back from the front of the house a bit would still allow east light into the kitchen. The house shown in many of the photos has just such an ell. In early times, this ell contained firewood storage, work areas, and the privy in northern climates.

AN ELL OFF THE WEST SIDE

Another ell could be added on the west in a similar fashion to house a master bedroom suite with its own bath. Again, a single-story structure set back from the front of the house would not obstruct the upper-floor windows. A formal design is thus created by having the central mass flanked by symmetric ells.

A lean-to (or outshot, as some call them) can be added off the north wall to virtually double the first floor area. It can continue the main roof pitch straight out until an 8-foot wall is left — a “cat-slide” roof. You can create a broken-back saltbox by lessening the pitch for the lean-to. As shown in the photos, you could also drop the roof down from the main roof a few feet to allow windows on the north wall of the second floor, but here the lean-to was only one bay wide and was a continuation of the ell. A greenhouse or sunroom lean-to could be added off the south side for solar heating.

The owners of the project house opted for a two-bay ell with a dirt floor. The framing is consistent with that of the main house but the roof pitch is 6-in-12.

A BROKEN-BACK SALTBOX

This house has a narrow two-story high lean-to creating a broken-back saltbox. Lowered interior ceilings are required for some rooms.

One could also add a cape ell off the north wall with a ridge perpendicular to the main roof. This could provide a huge family room with extra sleeping room above or possibly an open loft. One of my favorite add-ons aesthetically is a series of progressively shorter additions starting off at one end of the main house, creating a rhythmic effect. There is a distinct advantage to adding a structure against a two-story wall: The addition’s roof easily butts against the wall rather than uncomfortably meshing against roofs or cornices. Lean-tos with only a single roof plane are easily added.

This ell continues behind the house to become a lean-to for one bay.

A 5-inch by 13-inch header/girt between posts supports the lean-to rafters.

This late 1700s cape house in Adams, Massachusetts, had an early 1800s hall-and-parlor house (measuring 20 feet by 40 feet) built against it.

This classic house in New York has telescoping additions.

FRAMING THE HALL-AND-PARLOR GAMBREL

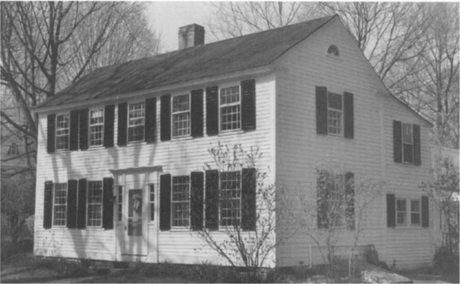

THE HALL-AND-PARLOR GAMBREL

The Dwight House in Old Deerfield, Massachusetts, built around 1754, has a gambrel roof as well as an ell and an attached barn.

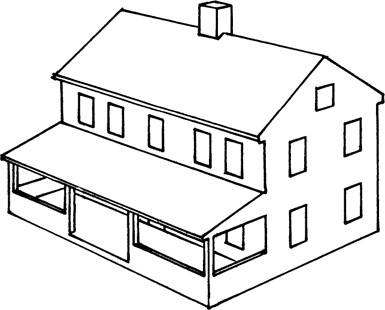

This house has a wrap-around porch.

A porch add-on extends the living space in summer.

You can also go up to gain more space. In fact, another story might be the most reasonable way to go considering the addition doesn’t need a foundation. The roof could easily become a gambrel shape with some dormers to provide a couple of rooms in the attic. The stairs to this new level would rise above the present stairs so as not to diminish space on the second floor. To frame a gambrel roof in timber, add a continuous purlin plate with braces on each side where the pitch changes. The purlin plates are supported by posts resting on the attic floor tie beams. Ceiling joists span between them much like the attic floor. Insulate the ceiling. Use planks nailed to the exterior side of the purlin plate for walls that are insulated just as the main house walls. A gambrel roof gives a finished room width of about 13 feet. A south-facing dormer in each bay will help light the rooms.

An important item lacking in many of today’s homes is the porch. I don’t mean open decks off the back of the house, but a place on the sunny side of the house with a roof and railings, a place where you can watch the world with some degree of privacy. Porches act as an extension of the living area in the warmer months and places where children can play on rainy days. They’re even nice for sleeping on hot summer nights. A porch should extend out at least 7 or 8 feet, have a solid or partially open railing for privacy, and a roof with sufficient overhang to keep rain off the porch floor. In some areas a screened porch is essential if it is to be enjoyed all summer.

All the framing and flooring should be of a rot-resistant species, and the floor should be pitched away from the house to shed water.

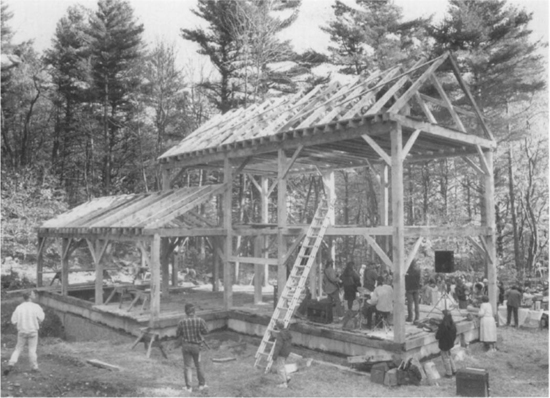

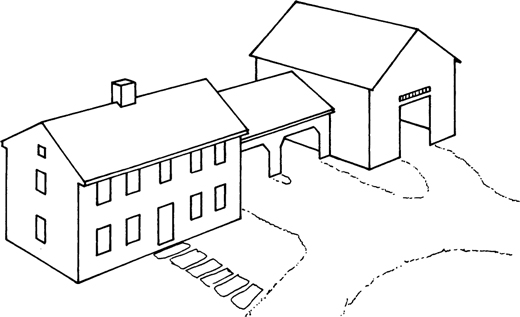

In the early days, the self-sufficient farmstead required a barn to shelter the livestock, store the crops, thresh the grains, and store equipment. Although the original New England barns were detached from the house, by the 1800s builders and farmers began moving and building barns so that they were connected to the house complex — see Hubka (1984). If a barn is attached to an ell off the east end of the house, the buildings can create a south-facing enclosure that is a great outdoor work area, even in winter.

The barn size is dependent on its use, of course, but most of the old New England barns were around 30 feet by 40 feet or larger. The equilateral triangle inscribed within its cross section was the most common geometric layout principle.

Even without animals, a barn-type building is still very useful, giving a work area for large projects, such as making cider, boat building, timber framing, and repairing equipment. It is also great storage for large bulky items like vehicles, tractors, boats, ladders, lumber, furniture, and sports gear. The main floor can be earthen with a wood-floored loft above. If the barn is attached, you can walk from the house through an ell and into the barn — a very handy feature in bad weather.

Adding a barn off the ell creates a classic New England farmstead.

No framing plans for the barn are included herein, but with the experience you have gained, it shouldn’t be too hard for you to work it out. You might want to study a few barns in your area to see how they were laid out and framed, then draw up some sketches and have a structural engineer check them over. Remember that geometry makes a shape pleasing to the eye.

I hope that this book has inspired you to build your own timber-framed house, one that stands proud and strong — a healthy house that enriches your life. If you build such a house, you will be continuing a tradition that is thousands of years old, a tradition that was nearly lost but now is strong again. Perhaps you will even go on to build for others. But, if I cannot add you to the growing list of timber-frame builders, then possibly you might become more involved in one of the associated professions. The craft needs woodland stewards who can manage our forests for sustained yields of quality products without destroying ecosystems. The craft needs more local sawyers to supply our timber needs, and tool makers that understand the old tools and how they were used. The craft also needs more architects, engineers, and building code officials that understand the principles of timber framing. And, of course, the craft needs more dedicated researchers to study the history of the craft and unlock its secrets.

Timber framing is not just a relic from the past or a curiosity. It is a viable house building technique that makes as much sense now as it ever did. I hope that you find it as rewarding as I have.