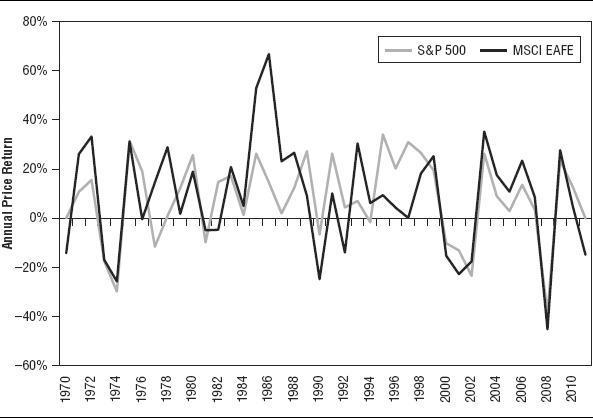

Exhibit 14.1 US Versus Non-US Stocks

Source: Thomson Reuters, S&P 500 Price Index, MSCI EAFE Price Index, from 12/31/1969 to 12/31/2011.

The relative strength (or lack thereof) of the US dollar is often cited as a symptom of myriad ills. As in, our economy is weak, therefore the dollar is weak. Our big budget deficit makes foreigners look down at us, weakening the dollar.

And then there’s the fear a weak US dollar self-perpetuates further weakness. For example, a weak dollar makes US imports more expensive—and because America is a net importer, that can drag on growth! And many fear a weak dollar portends weak stock returns.

It’s true a weak dollar makes imports more expensive. Don’t take that to mean a strong dollar is good! Or that when we have a strong dollar, people are happy about it. A strong dollar, as we had periodically in the 1990s, is also often blamed as the root of ills. Folks complain a strong dollar makes our exports too expensive, so no one wants to buy them, and that’s also hard on our economy. It’s as if folks believe there’s some perfect state of dollar/non-dollar balance—and if we’re not at that point, we’re headed for ruin.

This is a nonsense myth for several reasons. First, currencies are simply different flavors of money. One isn’t inherently better than another. There are both pros and cons to a weak and strong currency. Also, currencies aren’t appreciating assets like stocks. They’re commodities. If one is weak, it’s only weak relative to something else. So the dollar is weak because the euro or pound sterling or a bunch of currencies is strong and vice versa.

See it this way: If you believe a weak dollar is economically bad for the US, then a strong non-dollar must be good for the non-US world. Because the US is just 22% of world GDP,1 a weak dollar should be, by this theory, less bad for the world overall than a strong non-dollar is good! So on balance, a weak dollar should be good. No . . . great!

You know in your bones that’s silly. But that’s the logical conclusion if you believe a weak currency is economically bad—folks just don’t often think things through.

The potentially more costly myth is a weak dollar portends weak stock returns. Also nonsense. Weak or strong, the dollar’s relative strength doesn’t dictate market direction. Use the same logic from before. If the dollar is weak, that means the non-dollar is strong. And if a weak dollar is bad for US stocks, that means the strong non-dollar should be good for non-US stocks. If that were true, we could see it easily in history—US and non-US stocks would flip-flop directionally and be at least modestly negatively correlated.

But the reverse is true. US and non-US stocks usually move in the same direction, as shown in Exhibit 14.1. Not always and not at the same magnitude—but if US stocks are up, non-US stocks tend to be up. When US stocks are down, same thing. Not always perfectly, but enough to show US and non-US stocks aren’t moving in opposite directions.

Exhibit 14.1 US Versus Non-US Stocks

Source: Thomson Reuters, S&P 500 Price Index, MSCI EAFE Price Index, from 12/31/1969 to 12/31/2011.

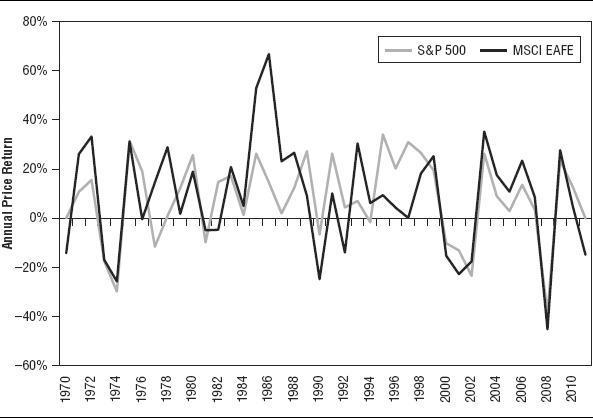

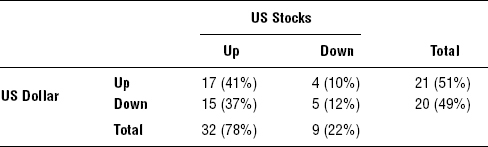

Here’s another way to test whether dollar direction impacts stocks. I call this a 4-box, and you can use it to test any number of beliefs. Exhibit 14.2 shows the two possible outcomes for US stocks in any given year and their frequencies—up or down. (This shows data back to 1971, which is after the end of the Bretton Woods era when major currencies began truly floating freely.) And it shows the two possible outcomes for the trade-weighted dollar and their frequencies. (The trade-weighted dollar is the correct way to do this because what we care about most is how the dollar fares against US trading partners. We don’t trade much with Bhutan, so we don’t care if the ngultrum is super strong or weak against the dollar.)

Exhibit 14.2 US Stocks Versus the US Dollar

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 03/07/2012. Trade-Weighted US Dollar Index,2 S&P 500 Total Return Index,3 from 12/31/1970 to 12/31/2011.

Combined, you get frequencies for the four possible annual outcomes: stocks and the dollar both up, stocks up and the dollar down, stocks down and the dollar up, or both down.

First, what should always smack you in the face is US stocks are up more than down—much more—a big 78% in this period. (Get that imprinted in your DNA, and you’ll see more investing success: Stocks rise much more than they fall.) Second, whether the dollar was up or down was effectively a coin flip. There’s no evidence the dollar is unidirectional.

Then, the most common outcome? The dollar and stocks both up—41% of all years. Which isn’t surprising once you accept stocks rise more than fall.

And where’s the proof a weak dollar is bad for stocks? If you believe that, the data should show that when the US dollar is down, most often, US stocks are down, too. Not so. When the US dollar was down historically, stocks were three times more likely to be up than down—37% of all years to 12% of all years. (Again, stocks rise more than fall.)

When stocks are down, it’s a coin flip whether the dollar is up or down because, in general, it’s just a coin flip whether the dollar is up or down. There’s no conclusion to be had here regarding the dollar’s impact on stock market direction because over long periods, there is no dollar impact on stock market direction.

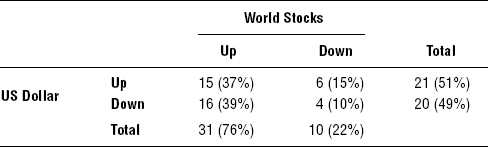

Exhibit 14.3 shows the same thing but with world stocks. Again, world stocks are up more than down. And when the US dollar is down, world stocks are near four times as likely to be up versus down (39% of all years versus 10%). And, once more, there’s no conclusion to be drawn because dollar direction doesn’t impact world stock market direction. Can’t get more clear and simple than that.

Exhibit 14.3 World Stocks Versus the US Dollar

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 03/07/2012. Trade-Weighted US Dollar Index,4 MSCI World Total Return Index with net dividends,5 from 12/31/1970 to 12/31/2011.

Now, in the very near term, currency movements can impact your portfolio return. For example, if you’re a US investor and own a UK stock, and the stock price doesn’t move but pound sterling appreciates 10% versus the dollar, the value of that UK stock has effectively appreciated 10% for you! And if pound sterling falls 10%, then the value of the stock similarly falls for US investors. If currency exchange rates move more than stock prices (as can happen), currency values can have a bigger impact on US dollar returns of foreign stocks than stock prices! Yowza!

If you’re a global investor (which I recommend for most stock investors) and are fully and appropriately diversified globally, that’s a lot of currencies to track. Should you quit your job now to become a currency trading expert?

Nah. If you have a long time horizon (as most readers of this book likely do), over time, because currencies are inherently zero-sum and irregularly cyclical, currency impacts on a global portfolio net out to close to zero.

What about investing directly in currencies? Feel free, but know currencies are notoriously volatile. Yet, long term, investors don’t get paid for that volatility. If you want to trade currencies for gain, you must be a consummate short-term market timer. That’s incredibly tough. If you know how to do that well and consistently, then you don’t really need my help or this book.

When folks say a too-weak (or sometimes, too-strong) dollar spells doom for stocks, ignore it. There’s no evidence it’s so, and no fundamental reason for it, either. Alternatively, you could exploit the fear as a minor bullish factor because fear of a false future factor is nearly always bullish. Yes, something might spell doom for stocks, but it won’t be the dollar on its own.

Notes

1. International Monetary Fund Economic Outlook Database, April 2012.

2. The trade-weighted United States dollar index is computed by the Federal Reserve. The base is 1975–76 = 100 and 10 countries are used in computing the index. The index includes the G-10 countries (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) weighted by the sum of the country’s world trade during the 1972–1976 period.

3. The S&P 500 Total Return Index is based upon GFD calculations of total returns before 1971. These are estimates by GFD to calculate the values of the S&P Composite before 1971 and are not official values. GFD used data from the Cowles Commission and from S&P itself to calculate total returns for the S&P Composite using the S&P Composite Price Index and dividend yields through 1970, official monthly numbers from 1971 to 1987 and official daily data from 1988 on.

4. The trade-weighted United States dollar index is computed by the Federal Reserve. The base is 1975–1976 = 100 and 10 countries are used in computing the index. The index includes the G-10 countries (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) weighted by the sum of the country’s world trade during the 1972–1976 period.

5. See note 3.