#4: THE HERMANS

| ALL-TIME #4 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Riggs Stephenson | 1932 |

| Babe Herman | 1933–34 |

| Chuck Klein | 1935–36 |

| Ethan Allen | 1936 |

| Billy Herman | 1937–41 |

| Wimpy Quinn | 1941 |

| Charlie Gilbert | 1941–42 |

| Hal Jeffcoat | 1949–53 |

| Smoky Burgess | 1949 |

| Ralph Kiner | 1953–54 |

| Ted Tappe | 1955 |

| John Goryl | 1957–59 |

| Billy Williams | 1959 |

| Charlie Root (coach) | 1960 |

| Vedie Himsl (coach) | 1960 |

| Verlon Walker (coach) | 1966–70 |

| Hank Aguirre (coach) | 1972–73 |

| Vic Harris | 1974–75 |

| Harry Dunlop (coach) | 1976 |

| Randy Hundley (coach) | 1977 |

| Mike Roarke (coach) | 1978–80 |

| Jack Hiatt (coach) | 1981 |

| Lee Elia (manager) | 1982–83 |

| Charlie Fox (manager) | 1983 |

| Don Zimmer (coach) | 1984–86 |

| (manager) | 1988–91 |

| Gene Michael (manager) | 1986–87 |

| Billy Connors (coach) | 1992–93 |

| Glenallen Hill | 1994 |

| Brian Dorsett | 1996 |

| Jeff Blauser | 1998–99 |

| Jeff Pentland (coach) | 2000–02 |

| Doug Glanville | 2003 |

| Jason Dubois | 2004–05 |

| Ben Grieve | 2005 |

| Freddie Bynum | 2006 |

| Rob Bowen | 2007 |

| Scott Moore | 2007 |

| Eric Patterson | 2008 |

| Joey Gathright | 2009 |

| Ryan Freel | 2009 |

| Pat Listach (coach) | 2011–12 |

| Dale Sveum (manager) | 2013 |

| Chris Valaika | 2014 |

| Dave Martinez (coach) | 2015 |

Billy Herman was born in New Albany, Indiana, right across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, on July 7, 1909. As were many players (and just plain folks) born in that era, William Jennings Bryan “Billy” Herman was named after a popular politician of his day. During his playing career he was known for his stellar defense and consistent batting, setting many National League defensive records for second basemen. He still holds the NL mark for most putouts in a single season (466 in 1933), and the most years leading his league in putouts (seven).

He broke into the major leagues in 1931 when the Cubs purchased his contract from AAA Louisville for $50,000. He asserted himself as a star the following season, starting all 154 games in 1932; he recorded 206 hits, scored 102 runs, and batted .314. A fixture in the Chicago lineup over the next decade, Herman was a consistent hitter and solid producer. He regularly hit .300 or higher, peaking at .341 in the pennant year of 1935, and the following year set a career high with 93 RBI.

After a sub-standard offensive year in 1940, Herman was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers early in their pennant-winning 1941 season for Johnny Hudson, Charlie Gilbert, and $65,000. Along with the earlier trade of Augie Galan, this was one of the deals that started the Cubs on their decline of the 1940s, stemmed only by the 1945 pennant.

Before Hall of Famer Billy Herman, another Herman, Babe Herman, wore #4 for two years, 1933 and 1934. No relation to Billy, Babe was best known for a baserunning gaffe he committed in 1926 while a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers. (He hit a double off the wall with two runners on base, but both of them stopped at third; when Herman tried to stretch the double into a triple, the Dodgers wound up with all three runners on third base, whereupon the third baseman tagged all three. Since only one runner was entitled to the base, Herman was said to have “doubled into a double play.”)

While baserunning wasn’t his forté, Babe could swing the bat. He had a .324 lifetime average and hit .296 with 30 homers and 177 RBI in 975 at-bats as a Cub after being acquired from the Reds in 1932 for four players. Two years later, he was traded to the Pirates.

Ralph Kiner (1953–54) had two decent years in the Cubs outfield, hitting 50 homers in the blue pinstripes. Acquired on June 4, 1953 from the Pirates in a 10-player deal (massive trades were a popular device for teams in the 1950s, especially bad teams like the Cubs and Pirates, hoping major changes would improve their lot—it almost never worked), Kiner’s better years were behind him. He was sent to Cleveland after the 1954 season. Had he not had serious back problems, he might have hit over 500 homers. As it was, he hit 369 homers in 10 seasons—including an unmatched seven consecutive NL home run crowns (typical for those Cubs teams, the first year of his career without a home run title was as a Cub). His slugging prowess—and ability to tell stories featuring multiple Hermans—got him elected to the Hall of Fame, and sent him to a long career as a broadcaster with the New York Mets.

Popular Riggs Stephenson (1932) was the first wear of #4 switching to #5 the following two seasons. Stephenson, a swift outfielder who spent his early years with Cleveland as an infielder, had suffered some shoulder injuries and was therefore made available to the Cubs in 1926. The next year he had a terrific season, hitting .344, and two years later his .362 average helped lead the Cubs to the pennant. In that 1929 season, each of the three Cubs starting outfielders (Stephenson, Kiki Cuyler, and Hack Wilson) had over 100 RBI, the first time that feat was accomplished in National League history.

At .336, Riggs Stephenson’s lifetime batting average is the highest of any eligible batter who is not in the Hall of Fame. That average still ranks 22nd all-time in baseball history, and is the highest in the history of the Chicago National League ballclub (tied with Bill Madlock, though Stephenson batted almost 2,000 more times as a Cub). Had it not been for the shoulder injuries, which limited him to only four seasons of 136 or more games in his nine years with the Cubs, Stephenson might well be in the Hall of Fame today.

Ethan Allen—neither the early American patriot nor the furniture store—wore #4 in 1936, his only year as a Cub in a thirteen year career. He had been acquired in the deal that sent Chuck Klein back to Philly, but he was sold to the St. Louis Browns at season’s end. Wimpy Quinn (1941) pitched in three games—all with a different number: #4, #16, and #18. Hal Jeffcoat (1949–53) was a pitcher—wait, no he wasn’t, no, wait, yes he was—well, let us explain. Jeffcoat was an outfielder with little pop or sizzle, but obviously, a strong arm. In 1954 he pulled what we might today call the “reverse Ankiel” and switched to pitching. He also switched numbers, from #4 to #19, and had some success as a reliever in 1955, at which time the Cubs traded him to the Reds. And Billy Williams spent his September callup in 1959 wearing #4 for the fifth-place Cubs: 18 games, 33 at-bats, and a .152 average. You’d never have guessed that the skinny kid from Mobile, Alabama was on his way to the Hall of Fame.

And after that, much like #3, #4 became dominated by coaches and managers, starting with former great Cubs pitcher Charlie Root in 1960. With the sole exception of Vic Harris—who came over from the Rangers in 1974 and demanded to have his Texas number (and whose .191 average over two seasons made the Cubs think twice before listening to the likes of Vic Harris again)—no player wore #4 between Williams in ’59 and Glenallen Hill, he of the rooftop bomb (hit while wearing #6 in 2000), in 1994. The best-known #4s were managers. Lee Elia started the trend with #4—the four-letter words in his fabled post-game tirade in 1983 were a different matter. Elia’s interim replacement Charlie Fox, later followed by Gene Michael and Don Zimmer, kept #4 in the manager’s office through most of the 1980s. Zimmer had worn #17 as a Cubs player in 1960 and 1961, but chose #4 when he returned as a coach in 1984 under manager Jim Frey. After Michael was fired, Zim reclaimed it when he came back to manage in 1988.

Since its return to player circulation, we cannot say that #4 has been worn with any distinction. It did see a moment of October glory, however. Doug Glanville, who had worn #1 and #8 in his original Cubs incarnation, wore #4 on third base following a game-winning triple in the top of the 11th inning in Game 3 of the 2003 NLCS. The #4s to follow were stranded somewhere before they got to third: Jason Dubois (2004–05), Ben Grieve (2005), Freddie Bynum (2006), Rob Bowen (2007), Scott Moore (2007), Eric Patterson (2008–Corey’s brother, joining a long list of Cubs brother acts), Ryan Freel (2009), and Chris Valaika (2014). Freel is remembered for a couple of things, one funny, one sad. Freel claimed to have an invisible friend named “Farney,” who Freel said was “a little guy who lives in my head who talks to me and I talk to him.” Three years after his brief, 14-game tenure with the Cubs, Freel committed suicide and it was learned he had traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a disease more prevalent in the NFL and NHL, which strikes athletes who have had multiple concussions. Freel was the first MLB player so diagnosed.

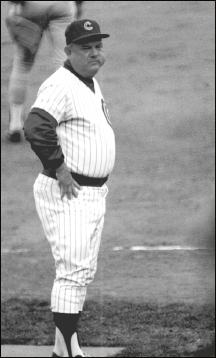

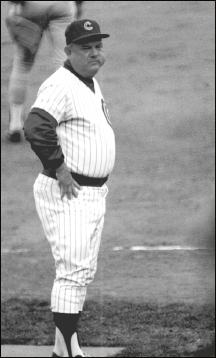

Baseball lifer Don Zimmer brought plenty of life to the North Side as a player, coach, and manager.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #4: Brian Dorsett (1996). For some unexplainable reason, GM Ed Lynch decided that it was a good idea in the 1995–96 offseason to sign a thirty-five-year-old journeyman catcher who had failed for five different teams prior to 1996. Even worse, manager Jim Riggleman put him on the Opening Day roster. He started nine games behind the plate; somehow the Cubs managed to win six of them despite his .122 batting average. He was sent to the minors in June and released at the end of the season, never again reaching the majors.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #4: Chuck Klein (1935–36). He had put up big years for the Phillies from 1929–33, but immediately declined when he put on a Cubs uniform. Times were tight during the Depression, and he was traded to Chicago just months after capturing the 1933 Triple Crown (the Phillies were more intent on the $65,000 in the deal than the three live bodies sent back to the Baker Bowl). Wearing #6 in 1934, Klein switched to #5 for the following two seasons. When he got off to a bad start in ’36, the Cubs sent him back to the City of Brotherly Love. Though some could quibble with his eventual selection to the Hall of Fame, there’s no argument that his 25 home runs in 148 games as a Cub had little to do with the discussion either way.

Cubs Unis, Part I: Dressed for Success

One of the sidebars planned for this book was a brief history of the Cubs uniform. This is impossible. There are enough variations of the Cubs uniform to do a whole separate book (and for anyone planning on doing that, this book certainly proves that such an endeavor has an audience). This task was made easier by Dressed to the Nines by Marc Okkonen, at the Baseball Hall of Fame website, and by Paul Lukas of ESPN.com, the last word on all things uni related.

What follows are some of the most intriguing looks in Cubs fashion and the year they first appeared. The list is broken into three parts (1871–1932, 1933–81, 1982–2015). The other two parts are in the chapters immediately following this one.

1889: Hit Like an Egyptian—Starting in 1871, when the National Association forebears of the Cubs took to the diamond for pay, the team went through several styles. At various times in those early days, the club wore ties, pillbox caps, and high stockings, often white to go with the team’s earliest name. For team president Albert Spalding’s fabled round the world trip in 1889, Cap Anson’s pre-Cubs posed on the Sphinx in their collared uniforms and you could read “Chicago” all the way from Cairo.

1900: Red Socks—Imagine the Cubs hosed in red? At the turn of the last century, they weren’t really even known as the Cubs and the team we know as the Red Sox did not even exist. And Chicago’s socks were probably closer to maroon, but the club was still getting its feet wet. Frank Chance was a reserve catcher, Joe Tinker was still toiling in the minors, and Johnny Evers was just a teen growing up in Troy, New York.

1908: Cubby Bat—The team, now known as the Cubs, introduced the bear inside the “C” in silhouette and holding a bat. That emblem would be over every player’s heart as the Cubs took the World Series that fall. The bear would return many times in many different forms through the years, but championships would be a different matter.

1909: Cadet Cubs—The two-time defending world champions were hard to miss, but the Cubs added a cool wrinkle to their pinstriped road uniforms. Called the “cadet collar,” it spelled out “Chicago” vertically in white letters on a dark blue background. Next to it was “Cubs” spelled with the big “C,” the first time that iconic logo appeared on the unis.

1932: Lots of Sewing—The year the Cubs added numbers to their uniforms in midseason they broke a few thimbles sewing on the new digits. The Cubs had four different uniforms: two each for home and the road. To be honest, the uniforms from this period—from 1931 up until the boys started leaving for the war in 1942—looked more like future White Sox garb than old-time Cubs togs.