#6: SMILIN’ STAN

| ALL-TIME #6 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Charlie Grimm (player-manager) | 1932 |

| Frank Demaree | 1933, 1935–36 |

| Chuck Klein | 1934 |

| Stan Hack (manager) | 1937–47 1954–56 |

| Dewey Williams | 1946 |

| Jeff Cross | 1948 |

| Frankie Gustine | 1949 |

| Wayne Terwilliger | 1949 |

| Bill Serena | 1949–53 |

| Fred Richards | 1951 |

| Jack Littrell | 1957 |

| Chuck Tanner | 1958 |

| Earl Averill | 1959–60 |

| Jim McKnight | 1960 |

| Dick Bertell | 1960–65, 1967 |

| Ed Bailey | 1965 |

| Johnny Stephenson | 1967–68 |

| Randy Bobb | 1968–69 |

| Johnny Callison | 1970–71 |

| Pete Reiser (coach) | 1972 |

| J.C. Martin (coach) | 1974 |

| Tim Hosley | 1975–76 |

| Barney Schultz | 1977 |

| Larry Cox | 1978 |

| Ted Sizemore | 1979 |

| Mike O’Berry | 1980 |

| Les Moss (coach) | 1981 |

| Keith Moreland | 1982–87 |

| Joe Altobelli (coach) (manager) | 1988–90 1991 |

| Rey Sanchez | 1992 |

| Willie Wilson | 1993–94 |

| Mike Hubbard | 1995–97 |

| Glenallen Hill | 1998–2000 |

| Ross Gload | 2000 |

| Ron Coomer | 2001 |

| Darren Lewis | 2002 |

| Ramon Martinez | 2003–04 |

| Sonny Jackson (coach) | 2005–06 |

| Alan Trammell (coach) | 2007 |

| Micah Hoffpauir | 2008–10 |

| Bryan LaHair | 2011–12 |

| Alberto Gonzalez | 2013 |

| Ryan Sweeney | 2013–14 |

| Carl Edwards Jr. | 2015 |

Before Ron Santo, Stan Hack was the best third baseman in Cubs history. Smiling Stan liked numbers—he wore seven different uniform numbers and was the first Cub to wear #31 and #39—but that made sense since he came to the Cubs from a bank. “Stanley got out of the banking business just as fast as he could and is now trying to forget the experience,” The Sporting News said of the rookie in 1932. “Why can’t the fans of Chicago forget he was an incipient banker and admire him for what he is today?” It gives you an idea where banks stood in the public’s mind during the Depression. The Cubs were so impressed with his Pacific Coast League pedigree they paid $40,000 to bring him to Chicago.

Hack was a lifetime .301 hitter, batting leadoff from the left side and rarely striking out. He led the team in runs eight times and batting four times while twice pacing the NL in hits and steals. With almost 2,200 career hits, scoring over 100 runs six straight times in a lower-offense era, and being an above-average third-sacker, he did get a handful of Hall of Fame votes in the 1940s and 1950s, peaking at 4.8 percent of the vote and eventually falling off the ballot. He retired following a disagreement with manager Jimmie Wilson in 1943, but after Wilson was fired midway through the next season Charlie Grimm (the original #6, now wearing #40 for his second tour of duty as manager) coaxed Hack out of retirement. It was a good thing, too. Hack hit .323 in 1945, finishing 11th in MVP voting, and helped lead the Cubs to the pennant. He played in four World Series as a Cub—batting .348 in 18 Series games—and was a five-time All-Star. He tried to bring that talent to Cubs in the 1950s as manager, but in three years at the helm Hack never guided the team to higher than a sixth-place finish.

Truly, the Cubs should retire #6 in honor of Smilin’ Stan, not just because he was one of the greatest players in Cubs history, but because the number hasn’t been worn with much distinction since Stan’s last year as manager in 1956. Bill Serena wore it from 1949–53, just before Hack’s managerial stint, putting up mid-range power numbers (17 homers for a seventh-place Cub team in 1950, which earned him fifth place in the Rookie of the Year voting), but after that there were a number of players who either did little (Fred Richards, who went 8-for-27 in 1951, and then vanished from the baseball Earth), poorly (Jack Littrell, .190 in 1957); went on to more success elsewhere (Chuck Tanner in 1958, a part-time outfielder who had a long career as a manager, including six seasons with the White Sox and later winning a World Series with the Pirates in 1979), or players like Earl Averill (1959–60), who hit 11 homers with the Cubs and 44 overall, 196 fewer than his Hall of Fame father whose name he bears, or Jim McKnight (1960), who played in three 1960 games before returning two years later wearing #15, perhaps giving a legacy to his yet-to-be-born son, Jeff (who didn’t enter the world until 1963), who wore five different numbers for the New York Mets in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the 1960’s, #6 was turned over exclusively to catchers. Dick Bertell had two tours of duty with the ballclub and with the number (1960–65, 1967), hitting .252 as a Cub. He hit .302 in 1962 in about half a season’s work (77 games, 215 AB), becoming the last .300-plus hitting Cubs catcher—in anything more than just a handful of at-bats—until Michael Barrett hit .307 in 2006. Catchers young—Johnny Stephenson (1967–68) and Randy Bobb (1968–69); and old—Ed Bailey (1965)—wore #6 with little distinction. After Johnny Callison (1970–71) unsuccessfully tried to bring the achievements he’d had in Philadelphia wearing #6 to Chicago, the club turned the number over to coaches for several seasons. It wasn’t until 1975 that another player, backup catcher Tim Hosley, put #6 on his back. In his single season in Chicago (and one at-bat in 1976 before he was waived back to Oakland, whence he came), Hosley hit .255. He did manage one memorable moment in that Cub blue #6, though. On September 14, 1975, Hosley came to bat as a pinch hitter with the bases loaded and two out in the bottom of the ninth and hit a grand slam. The Cubs lost anyway, 13–7.

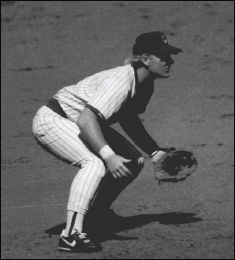

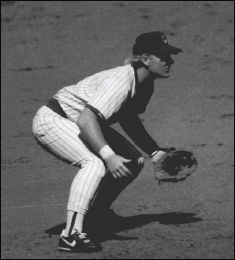

Ted Sizemore (1979) was yet another player who had tormented the Cubs as an opponent, mainly for the Cardinals and Phillies through the ’70s. Acquired through the theory: “If he’s on our side, he can’t beat us!” Sizemore tried his best to do that anyway, playing poor defense, hitting .248, and being seen as a malcontent. The Cubs dumped him to the Red Sox in August.Six seasons is the second-longest tenure in #6: Keith Moreland had played both baseball and football at the University of Texas and brought the gridiron mindset to the baseball diamond. Unfortunately, he didn’t really have a position he could play well. Acquired from his former team by GM Dallas Green, the Cubs tried the ex-Phillie behind the plate, but catching wasn’t his thing. He played third base…like the proverbial statue. Without a DH in the National League, the Cubs finally settled on right field once Bill Buckner was traded away and Leon Durham moved permanently to first base. Moreland was a bull in the outfield, but his bat made up for it (106 RBI in 1985 and 27 HR in 1987) and he loved getting and returning the “Hook ’em Horns” hand gesture with the bleacherites behind him.

In the second game of a doubleheader against the Mets at Wrigley Field on August 7, 1984, in the heat of a tight divisional race, Moreland embedded himself into Cubs lore forever. Mets pitcher Ed Lynch—later to become Cubs GM—hit Moreland with a pitch in the fourth inning. Moreland felt Lynch was throwing at him on purpose and charged the mound, tackling Lynch with one of his best football moves. It triggered a bench-clearing brawl which some say helped galvanize the Cubs to the NL East title. Interestingly, neither player was ejected from that game, which the Cubs won, 8–4. Lynch was traded to the Cubs two years later and they became teammates.

University of Texas safety Keith Moreland played a lot of positions and brought a lot of intensity to Wrigley.

After the 1987 season, the popular Moreland was traded to the Padres in a very unpopular deal that proved to be a bad one, too. It brought future Hall-of-Famer Rich Gossage to the Cubs, but he was done as a closer, and Moreland stopped hitting in San Diego. Moreland finished his career with stints in Detroit and Baltimore, but he lives on in Cubs lore. Moreland and Ernie Banks are the only players actually mentioned in Steve Goodman’s “A Dying Cub Fan’s Last Request,” the song that Dallas Green hated so much that WGN asked Goodman to write an upbeat Cubs song, which turned out to be “Go Cubs Go.”

Since Moreland’s departure, a number of coaches and backups have worn #6; coach Joe Altobelli, the manager of the 1983 world champion Orioles, also served one game as interim manager in 1991 between Don Zimmer’s firing and Jim Essian’s hiring. It belonged to coach Sonny Jackson (2005–06), who was brought on board by his buddy Dusty Baker (the two had played together in Atlanta and Jackson had been on Baker’s Giants coaching staff). No one seems to know exactly what Jackson did for the Cubs, except wear uniform #6.

Glenallen Hill (1998–2000), who also wore #4 and #34 in a separate Cubs stints (1993–94), had an impressive .304/.360/.546 line over five seasons as a Cub, but he lives forever at Wrigley for the jolt he put into a ball on May 11, 2000. The ball landed on the roof of a building on Waveland Avenue, across the street from the left-field bleachers at Wrigley Field, a shot estimated at over 500 feet. The game itself became a note in baseball history: at the time, it was the longest nine-inning game by time in major league history, running four hours, 22 minutes (that record has since been surpassed). And naturally, that mammoth blast was hit in a loss, 14–8 to Milwaukee.

Journeymen make up the remainder of the #6 clan to the present day: Ross Gload (2000), Ron Coomer (2001), Darren Lewis (2002), Ramon Martinez (2003–04), Micah Hoffpauir (2008), Bryan LaHair (2011–12), Alberto Gonzalez (2013), Ryan Sweeney (2013–14), and Carl Edwards Jr. (2015). LaHair, who pounded out 164 home runs in his minor-league career, 38 of them in the 2011 season to earn Pacific Coast League MVP and the chance to start for the Cubs at first base in 2012. He hit well enough in the first half (.286/.364/.519 with 14 homers in 61 games) to get an All-Star nod. But by the time he returned from that year’s Midsummer Classic in Kansas City, he’d lost the first-base job to Anthony Rizzo. He played a bit of right field the rest of that year, and never appeared in the majors after 2012. All-Star and out.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #6: Mike O’Berry (1980). Yet another in a very long line of mediocre backup catchers acquired by the Cubs in the 1970s and early 1980s, O’Berry was the player to be named later in the trade that had sent Ted Sizemore to the Red Sox on August 17, 1979, a deal completed after the season was over. O’Berry caught 19 games and hit .208 for the Cubs. His best contribution to the Cubs came after the 1980 season was over, when he was sent to Cincinnati for relief pitcher Jay Howell. In so doing, he began a trade chain that eventually helped win the Cubs the 1984 NL East title; Howell was sent to the Yankees for Pat Tabler, and Tabler eventually went to the White Sox in the deal that brought Steve Trout, a 13-game winner for the ’84 Cubs, to the North Side. Thank you O’Berry much.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #6: Willie Wilson (1993–94). Long after he had back-to-back 83- and 79-steal seasons for the Royals, led the AL in triples five times, helped lead Kansas City to five postseason appearances, the 1980 AL pennant, and the 1985 world championship, Wilson was signed as a free agent at age 37 before the 1993 season. He couldn’t hit triples any more (he had only one as a Cub), he couldn’t really steal bases any more (he swiped only eight in 122 games), and frankly, he couldn’t hit any more, either (batting .256 over a season-plus, more than thirty points below his lifetime average). Most of what Cubs fans remember about Wilson is his sulking on the bench when both Jim Lefebvre and Tom Trebelhorn wouldn’t play him. His constant whining gained him his outright release on May 16, 1994, with many months left on his two-year, $1.4 million contract (and back then, that was a solid financial commitment to a ballplayer). His nineteen-year career was history.

Cubs Unis, Part III: Into the Now

Hand it to the Cubs to become more conservative with their uniforms as they marched deeper into modern times. The Cubs have gone with a pinstriped top as their de rigueur home uniform from 1957 straight through the present. Still, they’ve tried a few things of note to stay styling—and moving merchandise.

1982: Goodbye Sister Disco—The Cubs shed baby blue on their road uniforms for a solid shade that more closely matched the stripes on the team’s home uniform. They also added a red stripe on the sleeve and on the top of the pants, which were a solid white, the only team in that era to wear white road pants.

1990: Dress Gray—Coming off their second NL East title in five years, the Cubs switched road uniforms. They went from blue tops to gray with nondescript block lettering for “Chicago.” The Cubs went from the best road record in the National League to middling success away from Wrigley and a fifth-place finish. New uniform, bad karma? Maybe the team ERA increasing by a full run had something to do with it, too.

1993: What’s Your Name—The Cubs put names on the back of the home uniforms (road unis had featured names since 1977). GM Larry Himes said it was partly because WGN was seen all around the country—apparently graphics and announcers prevented people watching at home from knowing who was batting. Once the names were on it was tough to go back. The Cubs did take them off in 2005–06 for tradition’s sake, but marketing brought them back after replica jersey sales plummeted.

1994: Strike Three—The third road look in a dozen years didn’t even make it through a full season as the Cubs—and everyone else—stopped playing in August. “Cubs” with a line under it wasn’t overly inspired, and the script format made the wording resemble “Cuba.” It was dropped three years later.

1997: New Bear in Town—The bear face sleeve emblem switched to the walking baby bear profile on the home and road uniforms. The Cubs also went back to block letters on the road unis. The result? They set a record for the most losses to start a season, but those basic road grays have become very popular with fans filling enemy venues from sea to shining sea to watch the Cubs come to town.

1997–2008: Alternate Ending—The Cubs first wore an alternate jersey on May 2, 1994; it wasn’t an official shirt, but the batting practice jersey, done in an attempt to break a long home losing streak. It didn’t work, as the Cubs lost to the Reds, 9–0. In 1997 they introduced an “official” blue alternate shirt, with the walking bear logo on the front and the forgotten National League insignia on the right sleeve harkening back to Chicago’s role as founder of the NL.

2014: Throwing It Back—To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Wrigley Field, the 2014 Cubs wore 10 different throwback uniforms during the season, one for each decade the team had played at Clark & Addison. They also helped the Phillies “celebrate” their “phutile” 1964 blown pennant by donning that year’s road togs at Citizens Bank Park, prompting some fans to hope the team might return to that look on the road full-time. The 2014 Cubs also introduced an alternate gray road uniform with “CUBS” in block letters and a numbering style to match. This uni, disliked by many, was worn far less often in 2015 than in its debut season.