#10: THE OL’ THIRD BASEMAN

| ALL-TIME #10 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Al Todd | 1940 |

| Bill Myers | 1941 |

| Clyde McCullough | 1943 |

| Billy Holm | 1944 |

| Paul Gillespie | 1945 |

| Bob Scheffing | 1946–50 |

| Mickey Owen | 1949 |

| Ron Northey | 1950–51 |

| Bob Schultz | 1952 |

| Bob Talbot | 1953–54 |

| Richie Myers | 1956 |

| El Tappe (player-coach) | 1958–59 |

| Ron Santo | 1960–73 |

| Billy Grabarkewitz | 1974 |

| Mike Sember | 1977 |

| Dave Kingman | 1978–80 |

| Leon Durham | 1981–88 |

| Lloyd McClendon | 1989–90 |

| Luis Salazar | 1991–92 |

| Steve Lake | 1993 |

| Scott Bullett | 1995–96 |

| Terrell Lowery | 1997–98 |

| Bruce Kimm (manager) | 2002 |

Ernie Banks may be “Mr. Cub,” but perhaps no player in Cubs history was as big a Cubs fan, living and dying with all of us as a WGN radio broadcaster from 1990 until his passing in 2010, as Ron Santo (1960–73).

You can’t get a real sense of his accomplishments and what he means to the Cubs franchise just by looking at his outstanding statistical line. That stat line, in fact, is even more remarkable when you consider the fact that he fought juvenile diabetes for nearly his entire life. Santo was the first high-profile professional athlete to reveal that he played sports at the major league level with this disease, which can debilitate and kill. In retrospect, knowing this makes his considerable accomplishments even more impressive. Even without that, his passion for playing the game could be seen every time he set foot on a baseball field.

Despite his diabetes—which he concealed even from his teammates for many years—Santo became one of the most durable players in baseball. He played in every game in 1961, 1962, 1963, 1965, and 1968. (Santo and Billy Williams played in a club-record 164 games in ’65, including two tie games, second-most games played in a season in major league history. Only Maury Wills, in the Dodgers’ three-game playoff season of 1962, played in more.)

By 1964 Santo had established himself as the best third baseman in the National League, enjoyed the first of his six All-Star selections, and finished eighth in the MVP voting with a 30 HR, 114 RBI season in which he batted .312/.398/.564 with 86 walks. The patient Santo walked 86 or more times for seven consecutive seasons, from 1964 through 1970, leading the league four times in a period when walks were less frequent than they are today. For those of you who key on OPS as a Hall of Fame indicator, Santo was in the top six in NL OPS four consecutive seasons, from 1964 through 1967. And at a time when Brooks Robinson was synonymous with the Gold Glove Award at third base in the American League, Santo took the honor five straight times in the NL (1964–68).

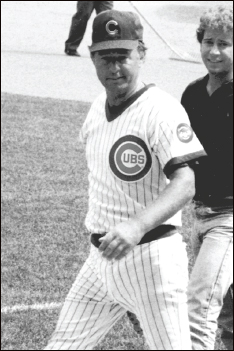

Ron Santo pretty much owned Wrigley Field for five decades as All-Star infielder, announcer, and hero.

The 1964 season was the first of four straight 30-homer years for Santo, and though he had “only” four 100-RBI seasons, he came oh-so-close to having eight straight; from 1963 through 1970 his RBI totals were 99, 114, 101, 94, 98, 98, 123, and 114, averaging 105 RBI over the eight seasons.

His best overall and also his most eventful season, was likely 1966 (though some might choose 1964 or 1969). He had career highs in BA, OBP, and SLG (.312/.412/.538) that year, leading the league in on-base percentage. He also set a club record (since broken) by hitting safely in 28 consecutive games.

Thirty years old and starting to feel the effects of a long career played with his disease, Santo’s numbers began to decline in 1970. He had another 100-RBI season, but his average dropped to .267. The following year his power also began to decline as he drove in only 88 runs, the first time in nine years he drove in fewer than 94.

On August 28, 1971, the Cubs honored him with Ron Santo Day at Wrigley Field. That was the day that Santo at last revealed publicly his battle with juvenile diabetes, beginning a lifelong association with JD foundations, including the local Chicago-area JDRF chapter, which has hosted the Ron Santo Walk to Cure Diabetes every year since 1974.

At the end of the 1973 season, the team that shoulda, coulda won it all for all of us was broken up, and Santo was among those traded away. Before leaving the Cubs, though, he became the first player to invoke the ten-and-five rule under the collective bargaining agreement signed after the 1972 strike (a player who had spent ten years in the major leagues, the last five with the same team, could veto any trade). The Cubs had agreed upon a deal to send Santo to the California Angels; the ballclub would have received in return two young lefties: Andy Hassler, who went on to have a middling career as a reliever/spot starter, and Bruce Heinbechner, a very highly-regarded prospect. Santo didn’t want to play on the West Coast and vetoed the deal. Eerily and sadly, Heinbechner was killed in a car accident the following March, driving to Angels spring training in Palm Springs, California.

The Cubs still wanted to deal Santo, and since his preference was to stay in Chicago, they worked out a trade with the White Sox, acquiring catcher Steve Swisher and three young pitchers: Jim Kremmel, Ken Frailing, and one of Santo’s future co-broadcasters, Steve Stone.

Santo’s number 10 was finally retired by the Cubs on September 28, 2003, the day after they clinched the NL Central title. It was a cloudy, cool afternoon, but the sun came out for about ten minutes, just when Santo was addressing the capacity crowd at Wrigley Field. He told the crowd, to a huge ovation, “This is my Hall of Fame.”

And while he was living, it had to be, as the Hall’s Veterans Committee denied Ron induction in 2003, 2005, 2006 and 2008. He was finally elected in 2011 by a special “Golden Era” Veterans Committee that included his longtime teammate and friend Billy Williams. Sadly, Santo had passed away a year earlier. The passionate speech delivered in Cooperstown July 22, 2012 by Ron’s widow Vicki was held in high regard by everyone in baseball as a tribute to her husband, who loved the game and the Cubs so much.

The Cubs might have retired #15. When Santo was first recalled on June 26, 1960, he replaced catcher Sammy Taylor on the roster while the Cubs were on the road. As was the practice in those days, if the shirt fit, the player wore it—thus Santo wore #15 until the Cubs came home, and Yosh Kawano issued him the #10 that he would make so famous.

Twenty-one other players have worn #10 for the Cubs, but virtually none of them had any lasting impact. During the Wrigley ownership era, the Cubs refused to retire uniform numbers, so Santo’s #10 was worn by nine subsequent players, starting with infielder Billy Grabarkewitz in 1974, and one manager, Bruce Kimm in 2002. (Kimm actually asked Santo’s permission before wearing it). Leon Durham wore No. 10 longer than anyone not named Santo, logging eight seasons in the ’80s. “Bull” Durham is famed most for a play he didn’t make in the 1984 NLCS; nuff said about that, we suspect.

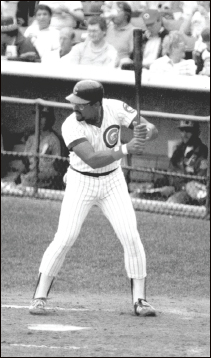

Leon Durham was never the superstar Chicago expected after Bruce Sutter was traded to get him and Bill Buckner was traded to open first base for him.

The best-known #10 besides Santo and Durham is probably Dave Kingman (1978–80), who hit homers of legendary length. Three of those home runs were hit in Dodger Stadium in a 10–7 Cubs win on May 14, 1978, leading Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda to give a profanity-filled tirade when asked what he thought of Kingman’s performance:

“What’s my opinion of Kingman’s performance!? What the BLEEP do you think is my opinion of it? I think it was BLEEPING BLEEP. Put that in, I don’t give a BLEEP. Opinion of his performance!!? BLEEP, he beat us with three BLEEPING home runs! What the BLEEP do you mean, “What is my opinion of his performance?” How could you ask me a question like that, “What is my opinion of his performance?” BLEEP, he hit three home runs! BLEEP. I’m BLEEPING pissed off to lose that BLEEPING game. And you ask me my opinion of his performance! BLEEP. That’s a tough question to ask me, isn’t it? ‘What is my opinion of his performance?’”

For those counting at home, that’s 27 fewer BLEEPs than Lee Elia would register in his fabled tirade three years later after a game at Wrigley against Lasorda’s Dodgers. But as to our opinion on other performances…

Most of the other players who wore #10s have been closer to 2s. Mike Sember (1977) went 1-for-4 in a September callup and since Kingman had the number the following year, Sember was assigned #29 when called up in September ’78. Lloyd McClendon (1989–90) caught and played a little outfield and first base, but his most memorable Cubs moment came in his very first Cubs at-bat. On May 15, 1989, having been just recalled from Iowa and inserted in the starting lineup, McClendon hit a three-run homer off the Braves’ Derek Lilliquist, snapping a five-game losing streak and helping the Cubs start a 14–5 run that would put them in first place. Steve Lake (1993), a backup catcher for the 1984 NL East champion Cubs wearing #16, returned for a curtain call in ’93, donning #10 because all the other numbers in the teens were taken. So was his bat, apparently; he hit .225 in 44 games.

For the rest of the 1990s #10 was given over to speedy outfielders. In a wonderful collision of name and attribute, Scott Bullett (1995–96) raced to seven triples in 1995 in only 150 at-bats, finishing sixth in the NL. His downfall was just as fast, hitting only .212 the following year and getting released. Terrell Lowery (1997–98) hit .241 in 29 at-bats with the Cubs before leaving for baseball exile with the expansion Devil Rays.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #10: Richie Myers (1956), who pinch-ran in three games and pinch-hit in one for the Cubs. He scored one run and grounded out to shortstop in his only at-bat, in a game the Cubs lost 7–3. Well, we told you he was obscure!

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #10: Mickey Owen (1949), who famously dropped a third strike as a Brooklyn Dodger in the 1941 World Series, allowing the Yankees a second chance, played three seasons as a Cubs backup, though only one wearing #10.

Running It Up the Flagpole: Retiring Numbers at Wrigley

The Cubs have retired only five numbers in their history: #10 for Ron Santo, #14 for Ernie Banks, #23 for Ryne Sandberg, #26 for Billy Williams, and #31 for Fergie Jenkins and Greg Maddux. For decades, the Wrigley ownership refused to retire numbers even for greats like Gabby Hartnett, Stan Hack, and Phil Cavarretta, and, given that the Yankees have retired twenty different numbers (including one for two different players), maybe it’s better that the Cubs haven’t run dozens of retired number flags up the flagpoles down the left- and right-field lines.

On the other hand, they’ve done pretty well in the five games played on number-retirement days, winning four, and there’s an explanation for the one loss. Maybe they should save these ceremonies for critical pennant-race games!

August 22, 1982, #14 retired for Ernie Banks: The Cubs defeated the Padres, 8–7, in front of a modest crowd of 23,601. The Padres blew a 5–0 lead, but the Cubs had to call on closer Lee Smith in the ninth with the tying run on base to save it. Two players in the game—Cubs Larry Bowa and Bill Buckner—had played against Ernie in the early 1970s.

August 13, 1987, #26 retired for Billy Williams: Chicago defeated the Mets, 7–5, in front of a larger-than-usual weekday afternoon crowd of 35,033 (the reasons they chose a Thursday for this ceremony are lost to the mists of time). As in Ernie’s ceremony game, the visitors blew a 5–0 lead, and once again, Smith was summoned with two out in the ninth—this time, he nearly blew the game, loading the bases on two singles and a walk before striking out Dave Magadan to end it. Irony: Billy was traded to the A’s after the 1974 season for, among others, Manny Trillo; Manny pinch-hit for the Cubs in this game.

September 28, 2003, #10 retired for Ron Santo: Santo’s emotional speech came prior to a meaningless game, the last of the 2003 regular season. The Cubs had clinched the NL Central the day before and though a handful of regulars started, they were all lifted by the middle innings. The sub Cubs blew a 2–0 lead and lost to the Pirates, 3–2, in front of 39,940.

August 28, 2005, #23 retired for Ryne Sandberg: Just a few weeks after his stirring Hall of Fame induction speech, Sandberg’s number was run up the right-field flagpole before 38,763 on a gorgeous afternoon. The Cubs’ play was beautiful, too—they demolished the Marlins, 14–3; the scoring barrage included two homers from Derrek Lee.

May 3, 2009, #31 retired for Greg Maddux and Fergie Jenkins: The Cubs retired #31 in honor of both pitchers before a 6–4 win over the Marlins on a sunny Sunday at Wrigley Field the year after Maddux retired. This was in the same manner that the Yankees retired #8 for both Bill Dickey and Yogi Berra in 1972. Maddux joined Jenkins in the Hall of Fame in 2014, and though Greg had his best years in Atlanta, he honored the Cubs fans who loved him by asking the Hall to put his face on his plaque with a logo-less cap.