#12: SHAWON

| ALL-TIME #12 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Charlie Root | 1932 |

| Mark Koenig | 1933 |

| Bob O’Farrell | 1934 |

| Jim Weaver | 1934 |

| Lon Warneke | 1935–36 |

| Ken O’Dea | 1937–38 |

| Gus Mancuso | 1939 |

| Rip Russell | 1940–42 |

| Johnny Hudson | 1941 |

| Billy Holm | 1943 |

| Chico Hernandez | 1943 |

| Roy Easterwood | 1944 |

| Dewey Williams | 1944–45 |

| Lou Stringer | 1946 |

| Dewey Williams | 1947 |

| Cal McLish | 1949 |

| Mickey Owen | 1950–51 |

| Bob Usher | 1952 |

| Tommy Brown | 1952–53 |

| Chris Kitsos | 1954 |

| Ed Winceniak | 1956–57 |

| Bobby Morgan | 1957–58 |

| Dick Johnson | 1958 |

| Jim Marshall | 1959 |

| Dick Gernert | 1960 |

| Nelson Mathews | 1960 |

| Mel Roach | 1961 |

| Len Gabrielson | 1964–65 |

| John Boccabella | 1966–68 |

| Gene Oliver | 1968–69 |

| J.C. Martin | 1970–72 |

| Andre Thornton | 1973–76 |

| Jerry Tabb | 1976 |

| Bobby Darwin | 1977 |

| Rudy Meoli | 1978 |

| Steve Macko | 1979–80 |

| Carmelo Martinez | 1983 |

| Davey Lopes | 1984 |

| Shawon Dunston | 1985–95, 1997 |

| Leo Gomez | 1996 |

| Mickey Morandini | 1998–99 |

| Ricky Gutierrez | 2000–01 |

| Angel Echevarria | 2002 |

| Dusty Baker (manager) | 2003–06 |

| Alfonso Soriano | 2007–13 |

| Chang-Yong Lim | 2013 |

| John Baker | 2014 |

| Kyle Schwarber | 2015 |

So who would you take? You’re Cubs GM Dallas Green, it’s June 1982, and you’ve got the first pick in the amateur draft. There are a lot of good players, a lot of future stars, but it comes down to Dwight Gooden or Shawon Dunston.

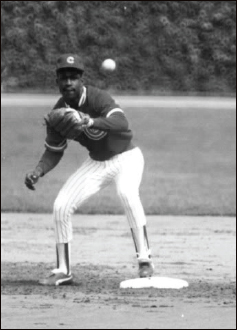

The Cubs chose Dunston, obviously, and received a dozen seasons of, shall we say, interesting baseball from him. He had speed but often ran himself out of plays with poor judgment. He had gap power but struck out more than one in every six at-bats in his career, exactly 1,000 K’s in all. He had range and an amazing arm, but if it hadn’t been for Mark Grace, many of his throws would have wound up heading in the general direction of Addison Street. He was one of the National League’s best shortstops during his first seven seasons with the club, before a herniated disc in his lower back cost him the better part of three seasons. There wasn’t a pitch he wouldn’t swing at—in addition to the 1K of whiffs, he walked only 203 times in 1,814 games, giving him a .296 lifetime OBP, not very good for someone who often batted leadoff. His shortcomings notwithstanding, he was a popular player for the Cubs, frequently lauded by broadcaster Harry Caray for one of his acrobatic plays in the field.

As to whether Gooden, with his erratic and self-destructive behavior, would have had an even better career in Chicago, it’s not ours to say. Dunston was, however, able to adapt. In 1997, during his second go-round with the Cubs, he played his first game as an outfielder after more than 1,200 games at shortstop. He added five years to his career as a spare flychaser, playing shortstop only 18 times after ’97, and making the postseason three times with three different teams (1999 Mets, 2000 Cardinals, and 2002 Giants).

Shawon Dunston could do it all, but it was how—and how often—he came through that made for a rocky relationship.

Before Dunston, no Cubs player had worn #12 for more than four seasons; it seems more a refuge for players in the early number days from another number. During the first two decades of Cubs uniform numbers, there was a large group of players who wore #12 and also had another number during their Wrigley tenure: Charlie Root (1932); Mark Koenig (1933); Jim Weaver (1934); Lon Warneke (1935–36), who had three 20-win seasons for the Cubs before he turned twenty-six in 1935, only to be dealt after 1936 to the Cardinals; Ken O’Dea (1937–38); Rip Russell (1940–42); Billy Holm (1943); Chico Hernandez (1943); Roy Easterwood (1944); Dewey Williams (1944–45), a backup catcher who squeezed in two at-bats in the 1945 World Series; Lou Stringer (1946); Cal McLish (1949), another pitcher who showed great promise in his early years with the Cubs only to have his best success elsewhere; and Mickey Owen (1950–51), who also wore #9 and #12 as a Cub, perhaps trying to escape the memory of his momentary failure to catch a strike in Brooklyn.

#12 was also worn by Tommy (Brown, 1952–53), Dick (Johnson, 1958; Gernert, 1960)…and Jerry (Tabb, 1974). Sorry, no Harry ever wore #12 for the Cubs. It wasn’t until 1968 that any Cub stayed in the number for more than two seasons. Backup catcher John Boccabella (1966–68), who wasn’t an original 12er (he wore #22 on his first callup in 1963), kept #12 while backing up Randy Hundley for most of three seasons; he was taken by the Montreal Expos in the 1968 expansion draft. He became far better known for the unique way the Jarry Park PA announcer would call out his name: “John Bocca-BEEEELLLLAAAAA!!!”

Andre Thornton first arrived in the major leagues with the Cubs in 1973, but he never really had a position. He played only part-time at first base while the Cubs were indulging the last good years of Billy Williams, and instead Andy became the poster child for the Lost Cubs of 1975. Thornton, the first Cub to wear #12 in more than three different seasons, who was sent to Montreal as a 1976 Olympic present for Larry Biittner and Steve Renko, never saw the postseason despite 253 homers and a .360 career on-base percentage. (He spent 1977–87 with Cleveland—nuff said.) Several other ’75 Cubs won championships within a few years of being dealt: Manny Trillo (Phillies), Bill Madlock (Pirates), Milt Wilcox (Tigers), and Rick Monday and Burt Hooton (Dodgers). Trading future ace Larry Gura and longtime ace Ferguson Jenkins, who had a decade of good pitching left in him, marred the final years of John Holland’s eighteen-year tenure as GM.

Pre-Dunston, #12 was inhabited by utilitymen, has-beens, and rookies who’d play their best baseball elsewhere. Of Rudy Meoli (1978), Steve Macko (1979–80), Carmelo Martinez (1983), and Davey Lopes (1984), the latter playing longer for the Cubs in another number than the more familiar #15 that he had worn as a Dodger, the only one we will memorialize here is Macko. He was an infielder of some promise who was cut down far too young from testicular cancer at age 27 in 1981. Steve’s dad Joe Macko was a member of the College of Coaches (in 1964, wearing #64), and later, for many years the clubhouse manager for the Texas Rangers. Steve had served as a Rangers batboy as a teenager when the Senators first moved to Texas.

Mickey Morandini (1998–99) became popular for his slashing hitting and running style and solid defense at second base for the 1998 Wild Card Cubs, but his average declined 55 points from 1998 to 1999, the Cubs suffered a 97-loss season, and Morandini departed as a free agent, almost as quickly as he was acquired for Doug Glanville after the 1997 season.

Perhaps the most controversial #12 was the only non-player to wear it, manager Dusty Baker (2003–06). Hailed as a potential franchise savior after leading the Cubs to within five outs of the World Series in 2003, Baker, noted as a player’s manager, lost control of the clubhouse the following season, with players calling the press box to complain about calls; Baker got into a war of words with broadcaster Steve Stone, leading to Stone’s leaving the club. By 2006, with Baker’s managing philosophies leading the Cubs to hack away at pitches rather than “clog up the bases” with walks, the Cubs put together a 96-loss season, one of the worst in club history, and Baker wasn’t retained…

As Alfonso Soriano and many others have shown, #12 is no quarterback’s number at Wrigley.

…which made #12 available to Alfonso Soriano (2007–13), signed by GM Jim Hendry to an eight-year, $136 million contract just weeks after Baker’s departure and the hiring of Lou Piniella, the biggest free-agent signing of that offseason. Soriano’s tenure in Chicago was controversial; as the recipient of the then-biggest contract in Cubs history, he was expected to help lead the team to a World Series title. Had they done so in the first two or three years of Alfonso’s deal, few would have complained about the big money. The Cubs did make the postseason in his first two seasons, and in part those came due to Soriano hot streaks, but the early playoff exits those years turned some fans against him. The Cubs returned him to his original team, the Yankees, in a deadline deal in 2013.

Backup catcher John Baker (2014), who is no relation to Dusty (whose given name is “Johnnie”), would have likely gone unremarked in these pages except for a memorable game July 29, 2014 against the Rockies. In the 16th inning, with the team out of pitchers, Baker took the mound and threw a scoreless frame. He then drew a walk leading off the bottom of the inning and scored the winning run, becoming the first Cub who was primarily a position player to post a pitching win since Ned Williamson—who did it in 1881. Baker’s performance in this game, and his willingness to interact often with fans on Twitter, has cemented his spot as a Cubs favorite.

Cubs 2014 first-round pick Kyle Schwarber is the newest wearer of #12. His prodigious home run against the Cardinals in the Division Series in 2015 landed on top of Wrigley Field’s right-field video board, and there it stayed. His 459-foot blast off Matt Harvey at Citi Field in the NLCS opener was last seen hopping aboard an outbound flight from LaGuardia. We shan’t speak of his feeling, but we’ll leave you with the obvious: the man can hit.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #12: Chris Kitsos (1954). They don’t come much more obscure than Kitsos, who, on April 21, 1954, came in to replace Ernie Banks (then in his rookie season) at shortstop in the bottom of the eighth in Milwaukee after Eddie Miksis had batted for Banks and grounded out with the Cubs trailing, 7–3. Kitsos had two assists and never played in the majors again. And that’s all there is to know.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #12: Bobby Darwin (1977). Darwin, who had hit 64 homers from 1972–74 as a regular outfielder for the Twins, suffered a power outage in ’75 and shuttled from the Twins to the Brewers to the Red Sox, from where the Cubs acquired him for Ramon Hernandez on May 28, 1977. It was a useless trade for both teams. Darwin played in just 11 games for the Cubs, going 2-for-12 before being released, and Hernandez pitched in 12 games for the Red Sox with a 5.68 ERA before being cut loose—the two releases coming within three days of each other.

Helmet Head

By 1954, just about every Cub was wearing a batting helmet. Even after batting helmets became the official rule in 1971, you could still wear a protective liner in your hat—a practice used all the way until 1979, when lone holdout Bob Montgomery of the Red Sox retired.

Protecting batters’ heads took long enough. A pitch had killed Cleveland’s Ray Chapman in 1920 and beanballs had severely impacted the careers of many players before that, specifically one of the greatest Cubs: first baseman and manager Frank Chance. “The Peerless Leader” crowded the plate, barely flinched as the fastest pitch bore in on him, absorbed the impact, got up, and took his base. Chance was drilled 137 times in just 1,274 games as a Cub, including five times in a 1904 doubleheader in Cincinnati in which he was knocked unconscious in the opener, played the second game, and then was drilled twice more. Though Chance later took to wearing a crude cap liner, he suffered the effects of the beanings for the rest of his life, which ended at age forty-seven.

The adoption of the helmet helped cooler—and safer—heads prevail. The first helmets were made of fiberglass, but plastic became the material of choice. In 1983, it was mandated that players wear a helmet with a flap on the ear that faced the pitchers (switch hitters generally went with a double flap). Ron Santo had been one of the first to go to an ear flap, wearing one as protection after having his left cheekbone fractured in 1966. While it is not clear who the first Cub to wear a helmet during a game was—perhaps ’54 leadoff man Bob Talbot?—the last to wear a helmet without an ear flap was Gary Gaetti. Grandfathered in from the old rule, Gaetti played his last game as a Cub on September 26, 1999. Third-base coaches, batboys, and some catchers still used flapless helmets in the field.

The Cubs were one of the first teams to wear the new Coolflo helmets made by Rawlings, in 2006. The helmet is ugly enough, but a venting system keeps players’ heads cooler than previous incarnations. The Cubs abandoned them in 2009 when too many of them were breaking. Broken helmets aren’t cool.