#13: LUCKY STAR AND ALL-STAR CLAUDE

| ALL-TIME #13 ROSTER | |

| Player | Years |

| Claude Passeau | 1939–47 |

| Hal Manders | 1946 |

| Bill Faul | 1965–66 |

| Turk Wendell | 1993–97 |

| Jeff Fassero | 2001–02 |

| Rey Ordonez | 2004 |

| Neifi Perez | 2004–06 |

| Will Ohman | 2006–07 |

| Andres Blanco | 2009 |

| Starlin Castro | 2010–15 |

Thirteen isn’t for everyone. It helps if you’re not superstitious, and it helps even more if you’re good. Claude Passeau was both. He was the first to wear #13 for both the Phillies and Cubs. Passeau arrived from Philadelphia in May 1939 in a trade for Kirby Higbe and two others having posted losing records in three years with the hapless Phils. In Chicago he reeled off eight consecutive winning seasons, leading the team in strikeouts seven times, complete games and ERA four times, and wins three times. Even today he still ranks 16th on the Cubs’ all-time wins list, right behind Greg Maddux and Carlos Zambrano. At age thirty-six he helped the Cubs claim the pennant, going 17–9 with a career-best 2.46 ERA. His first World Series appearance was magnificent: a one-hitter at Tiger Stadium in Game 3 of the 1945 Series. The good-hitting Passeau, who had 15 career home runs, even drove in a run with a sacrifice fly.

He was an All-Star five times—and still is the only Cubs pitcher to start an All-Star Game, doing so in 1946—but a lasting image is his serving up the game-ending homer to Ted Williams in the ’41 Midsummer Classic in Detroit.

Only nine other players have taken the plunge and worn the number that so many avoid that there’s a word—triskaidekaphobia—that specifically describes those who fear it. In keeping with our format, we will save one “obscure” player and one who you never thought of as a Cub for the end of the chapter, so let’s discuss the other seven.

After the 1940s, no Cub dared wear #13 until Bill Faul (1965–66), a free-spirited right-hander who might have been a precursor to the more open days of the 1970s. Faul was purchased from the Tigers after the 1964 season, had middling success (6–6, 3.54 in 17 appearances, 16 starts) in 1965, and then was relegated mostly to the bullpen by Leo Durocher in 1966. Durocher, an old-school sort if ever there was one, probably was turned off by Faul’s newfangled ideas, including self-hypnosis. Faul was sent to the minors in mid-season 1966, later surfaced briefly with the 1970 Giants, and then found himself out of baseball.

After Faul, #13 again sat hanging in the clubhouse, waiting for another free spirit to claim it. No one did so for nearly three decades, until Steven “Turk” Wendell (1993–97) donned it upon making his inauspicious major league debut on June 17, 1993 as a starter against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field. He allowed eight hits, two walks, and five earned runs in a game the Cubs would eventually lose, 11–10. Wendell had been acquired in one of the strangest deals in major league history, a trade made one week before the end of the regular season, on September 29, 1991, when the Cubs sent Damon Berryhill and Mike Bielecki to the Braves, desperate to win their first division title in nine years, in exchange for Wendell and Yorkis Perez, both thought of at the time as good pitching prospects.

Wendell didn’t do very well as a starter, but he improved when moved to the bullpen. Briefly made the Cubs closer in 1996, he led the team with 18 saves, which still stands as the lowest team-leading total since 1993. He might have done well had he continued in that role, but inexplicably, management signed Mel Rojas as a free agent to close in 1997. Rojas was so bad that he was dumped in a trade—along with Wendell and outfielder Brian McRae—to the Mets on August 8, 1997. Wendell turned in several decent years as a middle reliever/setup man for the Mets, Phillies, and Rockies before retiring after the 2004 season.

Jeff Fassero (2001–02) was the next to try his luck with #13. After several years as a swingman—starter and reliever—mostly with the Expos, Mariners, and Red Sox, the thirty-eight-year-old Fassero was signed in December 2000 as a free agent with the intention that he’d compete for a spot in the Cubs rotation. But an injury to Tom Gordon forced the Cubs to try Fassero as a closer, something he’d never really done (prior to 2001, he’d had 10 saves over his first three years as an Expo before converting to starting full-time). It worked, for a while. Fassero reeled off nine saves in April and when Gordon returned in May, Fassero became a top setup man, recording 25 holds. But the next year, instead of putting out fires, he became a torch, lighting up NL bats to the tune of a 6.18 ERA before being traded to the Cardinals for a pair of minor leaguers.

Neifi Perez (2004–06) will always be fondly remembered by Cubs fans, but not for anything he did while a Cub. On September 27, 1998, literally thirty seconds after the Cubs lost their final regularly scheduled game to the Astros Neifi, then playing for Colorado, hit a walkoff homer against San Francisco to beat the Giants, 9–8, forcing the September 28 winner-take-all tiebreaker, which the Cubs won, 5–3, to advance to the 1998 postseason. Little did we know that six years later, Neifi would join the Cubs in a desperation acquisition on August 19 after Nomar Garciaparra, who was supposed to help lead the Cubs to the postseason, got hurt. Neifi had the month of his life after the trade, going 23-for-62 with two homers, but the Cubs failed to qualify for the playoffs.

When Nomar went down again the following April, Neifi was pressed into service as the primary starting shortstop, a good six years after his best years had passed him by in Colorado. Manager Dusty Baker was quoted as saying, “Neifi saved us,” leading Cubs fans to wonder, “From what?” since that club finished with a 79–83 record.

The following year, with the club in disarray, Neifi was dispatched to the Tigers for a minor league catcher on August 20. He should send Jim Hendry a Christmas gift every year for the rest of his life, because Hendry got him from a 96-loss last-place team into the World Series.

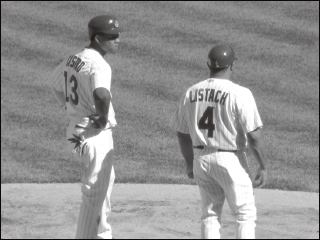

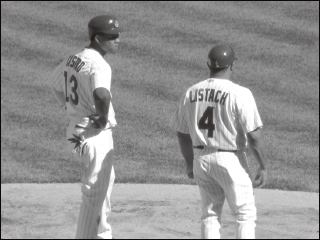

Starlin Castro confers with third-base coach Pat Listach.

Will Ohman (2006–07) claimed #13 after Neifi was dealt to Detroit; he seemed a bit of a number vagabond, having also worn #35, #45 and #50 in various other stints with the Cubs. Andres Blanco (2009), a slick-fielding, no-hit middle infielder, wore #13 briefly before it was claimed by Starlin Castro (2010–15).

Castro splashed his way onto the Cubs scene with a memorable debut game in Cincinnati, May 7, 2010. He homered in his first big-league at-bat and also tripled; the six RBI that came from those two hits set a record for a player in his first big-league game.

But Castro, who had barely turned 20 and hadn’t played above Double-A when he was called up to become the team’s starting shortstop, showed immaturity and stirred controversy. He had a 200-hit season and two All-Star appearances in his first three years. Some thought he lost focus at times on the field and as a result, made errors on routine plays. His hitting slumped through the Dale Sveum era and after a horrid start to 2015, Joe Maddon benched him, eventually returning him to the lineup as a second baseman.

Castro suddenly started to hit again, hitting .353/.373/.588 with six home runs in 47 games from August 11 through season’s end, becoming a big factor in the Cubs’ playoff run. With the Cubs signing Ben Zobrist, Castro became expendable and he was traded to the Yankees in December 2015 for Adam Warren and Brendan Ryan. Enduring the bad times and getting traded just as the Cubs stock up for the postseason? Well, #13 or no, that’s not very lucky at all.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #13: Hal Manders (1946). Manders, whose primary claim to fame is that Hall of Famer Bob Feller is his cousin, pitched in two games (one start) late in ’46. Claude Passeau’s season had ended due to a back injury and he had gone home in late August, presumably retired, so his #13 was available and, as was the custom in those days, if the club had an available shirt that fit and wasn’t being used, it would be reassigned. Manders was not retained for 1947, and Passeau came back for a 19-appearance (6-start) encore, reclaiming his number in ’47.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #13: Rey Ordonez (2004). Ordonez had been signed out of Cuba as a free agent by the Mets in 1993. They were dazzled by his glove, but quickly learned that he couldn’t hit. His glovework was good enough to keep him a regular for seven seasons with the Mets, but they dealt him to Tampa Bay in 2003 for a couple of minor leaguers who never made it. He was signed by the Padres in 2004, but he never played in the majors for them and was released in May. Cubs manager Dusty Baker, liking supposedly scrappy middle infielders with good gloves, asked GM Jim Hendry to sign Ordonez. He hit .164 in 23 games (22 starts) before being released; this eventually led Hendry to make the blockbuster Nomar Garciaparra deal at the deadline that year.

Gassaway Got Away

Of the more than 1,500 men who have worn a Cubs uniform since 1932, we have a number to go with every name…except for one. Charlie Gassaway. And it’s not for a lack of trying.

Gassaway was the starting pitcher in two games at the end of the 1944 season, both on the road, against teams long out of the pennant race. The fourth-place Cubs wound up 30 games behind the Cardinals, and they still had a double-digit lead on both opponents the final week of the season. The twenty-six-year-old southpaw from the eponymous locale of Gassaway, Tennessee, debuted on September 25, in the first game of a Monday doubleheader sweep of the Phillies at Shibe Park; he earned no decision in a 7–6 Cubs win. He started again four days later at Braves Field and lost, 5–1. The “crowd” for that Friday afternoon contest in Boston was 501.

Fifty years later, Kasey Ignarski was sifting through scorecards, media guides, and official documents in an attempt to verify every Cubs uniform number in history. But Gassaway’s number was not in any source or on either of the lists Kasey got from the Cubs in 1995 and 1997. A few years later, when Jack Looney was working on his book, Now Batting, Number… Looney contacted Kasey about Gassaway. Looney had found that Gassaway, though he never pitched again for the Cubs, had worn #3 in 1945 for the Philadelphia Athletics and #31 in Cleveland during his final season in 1946.

Kasey contacted the Boston Braves Historical Society to see if they had any source for scorecards from the game Gassaway pitched there in ’44. Given that the team moved from Boston to Milwaukee in 1953, the paucity of that day’s crowd, and the passage of time made it no surprise that this was a dead end. A search of Boston newspaper archives also proved unsuccessful. Attempts to find anyone in Philadelphia with information on the game he pitched as a Cub also proved fruitless. Al Yellon contacted Gabriel Schechter, a researcher at the Hall of Fame, to see if the Hall had any information. But Schechter’s research came up empty, too; there was nothing in his Cooperstown file mentioning a uniform number and no photos of Gassaway as a Cub.

Back in Chicago, Kasey searched the Chicago Tribune archives and found mentions of Gassaway in their game stories, but there was nothing on the number he wore. Kasey then went to his source for many past scorecard/program searches: AU Sports in Skokie. The 1944 programs they had did not list Gassaway on any roster—not exactly a surprise since he never pitched at home. There was no way on Earth to find out from the source, as Charlie Gassaway had already passed away by the time Kasey began his search in earnest,

So Gassaway’s is the one number we never found. Given that during the last week of September 1944, Polish resistance in Warsaw was being crushed, repeated British attempts to take the Dutch bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem were failing, and American soldiers were pushing their way to the German border, people’s minds were understandably focused on more than baseball.