#16 BITTERSWEET SIXTEEN

| ALL-TIME #16 ROSTER | |

| Player | Years |

| Burleigh Grimes | 1932 |

| Ed Baecht | 1932 |

| Lon Warneke | 1933–34 |

| Tex Carleton | 1935–38 |

| Ray Harrell | 1939 |

| Ken Raffensberger | 1940–41 |

| Wimpy Quinn | 1941 |

| Babe Dahlgren | 1941–42 |

| Jimmie Foxx | 1942 |

| Don Carlsen | 1948 |

| Hank Edwards | 1949–50 |

| Harry Chiti | 1950 |

| Bob Addis | 1952–53 |

| Howie Pollet | 1953–55 |

| Bob Will | 1957–58 |

| Bobby Adams | 1958–59 |

| Randy Jackson | 1959 |

| Jerry Kindall | 1960–61 |

| Ken Hubbs | 1962–63 |

| Roger Metzger | 1970 |

| Garry Jestadt | 1971 |

| Gene Hiser | 1971–72 |

| Whitey Lockman (manager) | 1972–74 |

| Rob Sperring | 1974–76 |

| Steve Ontiveros | 1977–80 |

| Bill Hayes | 1980–81 |

| Steve Lake | 1983–86 |

| Terry Francona | 1986 |

| Paul Noce | 1987 |

| Greg Smith | 1989–90 |

| Jose Vizcaino | 1991–93 |

| Anthony Young | 1994–95 |

| Dave Magadan | 1996 |

| Jeff Reed | 1999–2000 |

| Delino DeShields | 2001–02 |

| Sonny Jackson (coach) | 2003 |

| Aramis Ramirez | 2003–11 |

| Joe Mather | 2012 |

| Jeff Beliveau | 2012 |

| Darnell McDonald | 2013 |

| Rick Renteria (manager) | 2014 |

| Brandon Hyde (coach) | 2015 |

Number 16 is a number of great triumph and great sadness for Cubs fans. The sadness comes from wondering what might have become of Ken Hubbs (1961–63), one of the tragic figures in Cubs history. At age twenty he handled 418 consecutive chances without an error covering 78 games, both of which remained major league records for many years; the consecutive-chance record stood until 1982, when it was broken by ex-Cub Manny Trillo, then playing for the Phillies. Hubbs was a free swinger, but his .260 average and 49 RBI garnered him 19 of the 20 votes cast for the 1962 NL Rookie of the Year Award. (Pirate Donn Clendenon kept it from being unanimous.) Although Hubbs slumped the next year, he was a key part of a club with improving pitching and a lineup of future Hall of Famers Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, and Lou Brock, not to mention Ron Santo. Hubbs hated to fly and because of that, he decided to take flying lessons to conquer that fear. He earned his pilot’s license at age twenty-two, in the 1963–64 offseason. On February 15, 1964, just a week before spring training, he was killed after taking off in a snowstorm in Utah. Though the Cubs didn’t retire numbers in those years, it was announced that Hubbs’ No. 16 would not be reissued for the 1964 season. Hubbs also wore #33 during his September callup in 1961.

Though the Cubs only promised to keep Hubbs’s number out of circulation for one year, they let it lay vacant out of respect for six full seasons, when rookie hotshot Roger Metzger (1970) was called up and issued #16. Metzger was a pretty good prospect, but he was blocked behind Don Kessinger and Glenn Beckert at both the middle infield positions and was traded to Houston in the 1970–71 offseason for the forgettable Hector Torres. Metzger became the Astros’ regular shortstop for several seasons.

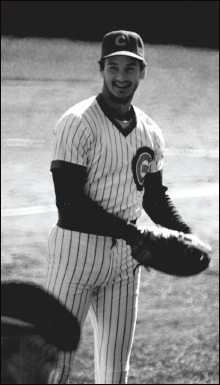

Future world champion winning manager Terry Francona shows his smile and a beard as a Cubs first baseman.

After Metzger left, the number was issued to a number of mediocre individuals, including the mediocre manager Whitey Lockman (1972–74), and after he was fired, to the non-prospect infielder Rob Sperring (1974–76). A future manager, Terry Francona, wore it in his brief Cubs career in 1986.

The same was the case prior to Hubbs being issued the number at the end of the 1961 season: it was either worn by well-known players after they were famous (Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes,1932, and Howie Pollet, 1953–55, who had been a key part of the Cardinals pennant winners in 1942 and 1946, but as a Cub posted a 4.19 ERA in two-plus seasons) or by players who became famous for not-so-wonderful reasons (Harry Chiti, 1950, who was to become famous as an original Met for becoming the player to be named later in a trade for himself, and Anthony Young, 1994, who set the major league record for consecutive pitching losses, 27, the season before the Cubs traded for him—and the Cubs still gave the Mets everyday shortstop Jose Vizcaino, who preceded Young in #16).

Then there were the guys who wore #16 who weren’t remembered by anyone, except in this book: Bill Hayes (1980–81), a catcher who played in five games for two of the worst Cubs teams ever; Paul Noce (1987), another middle infielder who couldn’t hit (.228 in 180 at-bats); Greg Smith (1989–90), ditto Noce; and Jeff Reed (1999–2000), who had a long career as a backup catcher with other teams, but his major distinction as a Cub was drawing the first pinch-walk by a major leaguer in Japan (in the Cubs/Mets game on March 30, 2000). Still others had more notoriety or recognition or just simple indecisiveness in other numbers (Wimpy Quinn was the first Cub to wear three numbers in one season, #4, #16, and #18; Bob Will, best known as #28 from 1960–63, and Dave Magadan, best known as a Met, Marlin, or Padre. His one year as a Cub produced the second-worst season average of his career, .254).

The ray of sunshine in the gloom is Aramis Ramirez (2003–11). Acquired in a salary-dump deal from the Pirates during the race in 2003, he wore #16 longer than any other Cub, and will be remembered as one of the top three third basemen in Cubs history (only Ron Santo and Stan Hack likely outrank him—and one can only hope Kris Bryant joins that company). Ramirez solved the longtime third-base problem that was created when Santo was traded away after the 1973 season—more than 100 different players were tried there in the next 30 years. When Ramirez departed for free agency and Milwaukee after the 2011 season, his Cubs total of 239 home runs ranked sixth in club history. Aramis’s career ended, ironically enough, when he hit into a double play as a Pirate in the 2015 wild-card game against the Cubs. The 115 regular-season DPs he grounded into as a Cub rank eighth in team history.

After A-Ram’s departure, the number drifted through mediocre players (Joe Mather, Jeff Beliveau, and Darnell McDonald) before returning to the management ranks with Rick Renteria in 2014. Renteria was just the third non-player to wear #16 with the Cubs. Coach Brandon Hyde now wears it, but only because Kris Bryant wanted the #17 that Hyde was sporting at the beginning of the 2015 season.

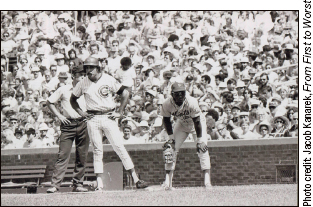

Steve Ontiveros, held on first by Met John Milner, covers up his Hair Club for Men coif.

A final perfect example of how the #16’s had to get their fame off the baseball field is Steve Ontiveros (1977–80). He had middling power (10 homers, 32 doubles) and hit. 299 for 1977’s half-season overachievers. But the balding “Onty” became best known in Chicago for his TV commercials for the “Hair Club For Men.”

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #16: Garry Jestadt, who was acquired in an April 1970 trade from the Montreal Expos, spent the rest of that season in the minors, and somehow wound up on the Opening Day 1971 roster. He pinch-hit three times, all late in blowout losses, not getting a single hit, and then was traded to San Diego on May 19, 1971 for backup catcher Chris Cannizzaro.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #16: Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx, who hit 534 career home runs and was second to Babe Ruth on the all-time list from his retirement in 1945 until Mickey Mantle passed him late in 1968, hit exactly 10 of those homers as a Cub, long after the prime of his career, in 1942 and 1944. Double-X did wind up with a long association with the Wrigleys, as he managed in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, started by P.K. Wrigley in the 1940s. Tom Hanks’s character in the film A League of Their Own, manager Jimmie Dugan, is said to be based loosely on Foxx.

Maybe They Shoulda Kept ’Em Blank

The Cubs and Braves are the only major league franchises in continuous operation since 1876, and the Cubs the only one that has stayed in the same city for those 133 seasons. The histories of the two ballclubs actually date back to their charter membership in the first professional baseball league: the National Association. Though it has never been classified a “major” league, the NA provided Chicago with its pro baseball debut in 1871 before the Great Chicago Fire that October idled the team for two years. Chicago had a thoroughly mediocre record of 77–77 in the NA when they weren’t being burned out or maneuvering to form the National League. Chicago won the inaugural National League pennant in 1876, the first of sixteen league titles they have won.

From 1876 through June 27, 1932—56 ½ seasons—the Cubs wore numberless shirts. And from June 30, 1932 through the end of the 2015 season—83 ½ seasons—the club has worn numbers on their backs.

So how did the team do, with blank shirts and with digits?

Without numbers: 4,276–3,143; .577

With numbers: 6,332—6,740; .484

We leave it to the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.