#19: MANNY AND THE MAD RUSSIAN

| ALL-TIME #19 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Harry Taylor | 1932 |

| Jakie May | 1932 |

| Charlie Root | 1933 |

| Bill Lee | 1934 |

| Red Corriden (coach) | 1937–40 |

| Barney Olsen | 1941 |

| Lou Novikoff | 1941–42 |

| Lon Warneke | 1942 |

| Doyle Lade | 1946 |

| Emmett O’Neil | 1946 |

| Hal Jeffcoat | 1948–49, 1954–55 |

| Dick Manville | 1952 |

| Joe Hatten | 1952 |

| Pepper Martin (coach) | 1956 |

| Bill Henry | 1958 |

| Moe Thacker | 1958 |

| Paul Smith | 1958 |

| Sammy Drake | 1960–61 |

| Elder White | 1962 |

| Daryl Robertson | 1962 |

| Billy Ott | 1962 |

| Jimmy Stewart | 1963–67 |

| Lee Elia | 1968 |

| Bill Heath | 1969 |

| Charley Smith | 1969 |

| Phil Gagliano | 1970 |

| Danny Breeden | 1971 |

| Pat Bourque | 1971–73 |

| Gonzalo Marquez | 1973–74 |

| Manny Trillo | 1975–78, 1986–88 |

| Pat Tabler | 1981–82 |

| Dave Owen | 1983–85 |

| Curtis Wilkerson | 1989–90 |

| Hector Villanueva | 1991–92 |

| Kevin Roberson | 1993–95 |

| Brooks Kieschnick | 1996–97 |

| Jason Hardtke | 1998 |

| Curtis Goodwin | 1999 |

| Jose Molina | 1999 |

| Gary Matthews Jr. | 2001 |

| Hee Seop Choi | 2002–03 |

| Damian Jackson | 2004 |

| Brendan Harris | 2004 |

| Mike DiFelice | 2004 |

| Enrique Wilson | 2005 |

| Matt Murton | 2005–08 |

| Tyler Colvin | 2009 |

| Bobby Scales | 2010 |

| Rodrigo Lopez | 2012 |

| Nate Schierholtz | 2013–14 |

| Dan Straily | 2014 |

| Jonathan Herrera | 2015 |

Lou Novikoff, “The Mad Russian,” was actually born in Arizona. The nickname came both from his last name and in reference to a popular radio character of the time portrayed by actor Bert Gordon. After posting a .363 batting average with 41 home runs and 171 RBI for the Cubs’ minor league Los Angeles Angels team in 1940, he was called up to the Cubs in 1941. He played only one of his four Cubs seasons as an outfield regular (1942), in part because of his eccentric personality. He was reputedly afraid of the ivy at Wrigley Field, thinking it was “poison ivy,” and this made him shy away from the wall. And, he once tried to steal third base with the bases loaded. When asked why he did it, he reportedly replied: “I got such a good jump on the pitcher.” In keeping with his oddball nature, he switched numbers frequently, also wearing #45 and two numbers that were eventually retired: #14 and #26. He switched to a military uniform in 1944 and wore a Phillies uniform upon his return stateside in 1946. After his retirement from the major leagues, he continued to play softball under the name “Lou Nova,” which he had also used before his major league career; he was eventually inducted into the Softball Hall of Fame in Long Beach, California.

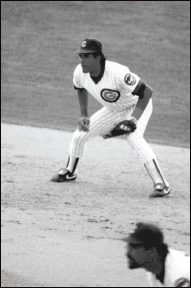

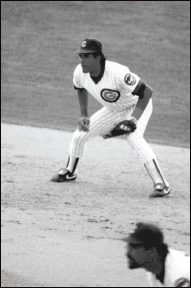

Manny Trillo’s method of getting the ball to first base after fielding it at second—seemingly stopping and reading the NL president’s signature on the ball before firing it sidearm—became his trademark during his four solid seasons in Chicago from 1975–78. Trillo was traded to the Phillies along with Greg Gross and Dave Rader in an eight-player deal that brought Barry Foote, Ted Sizemore, Jerry Martin, Derek Botelho, and minor leaguer Henry Mack in a deal that clearly was better for the Phils. Trillo played every inning—and hit .381 in the epic NLCS—of Philadelphia’s October run to the world championship in 1980 and set a record for consecutive errorless games for a second baseman in 1982 (a record since broken by Ryne Sandberg).

A singles hitter with little power, Trillo’s best year as a Cub was 1977, when he hit .280; his value to the club was primarily defense. After stops in Montreal, San Francisco, and Cleveland, the Cubs reacquired the popular second sacker (some bleacher fans used to chant when he came to bat: “One-O! Two-O! Trillo!”) and he hit .296 and .294 as a solid backup in 1986 and 1987. By 1988 he had declined.

Manny Trillo did two tours at Wrigley, gobbling up grounders and making fans happy along the way.

One of the funnier sights of the end of the 1988 season occurred on September 20 when Randy Johnson, a September callup for the Expos, faced the Cubs for the first time. In the top of the seventh, Johnson, who threw his first complete game that night, singled for his first major league hit. When the 6-foot-11 Johnson reached first base, TV cameras showed him standing next to first baseman Trillo, who’s listed at 6-foot-1 but might be shorter than that. Trillo looked like a batboy standing next to the Big Unit.

Then there’s the curious case of Hal Jeffcoat, who had been a middling-hitting outfielder starting in 1948, when he hit .279 playing mostly full-time (473 AB). That got him shipped to the bench, where he played part-time for the next five seasons, wearing #19 in 1948 and 1949, switching to #4 from 1950–52, to #3 in 1953, and then back to #19 when, at age 30, he converted to hurling after the ’53 season. Jeffcoat was photographed wearing #3 for his pitching debut in an exhibition game against the Orioles in New Orleans on April 7, 1954, but the likelihood is that it was a leftover jersey from ’53 worn in spring training. Though coach Bob Scheffing said after Jeffcoat’s debut that “he has the equipment to win,” Jeffcoat spent most of 1954 in the bullpen, going 5–6 with 5.19 ERA in 43 games, starting only three of them. The next year he cut that figure down to 2.95 in 49 relief appearances and one start, and naturally, that got him immediately shipped out of town, dealt to Cincinnati that offseason for catcher Hobie Landrith, a career .233 hitter with no pitching promise.

The rest of the #19s bear little more than brief mentions. The only other one to wear the number for more than three seasons was Jimmy “Not The Actor” Stewart, a reserve infielder from 1963–67. Lee Elia (1968), later to become famous for a tirade given to a radio reporter while Cubs manager in 1983, went 3-for-17 as a Cubs player; Bill Heath (1969) had his moment in the sun when he caught most of Kenny Holtzman’s first no-hitter on August 19, 1969. It was only “most of” a no-hitter because in the top of the eighth, Tommie Aaron fouled a ball off Heath’s finger, breaking it; Heath left the game and never played again. Others who sported #19 briefly—but in less pain—included Charley Smith (1969), Phil Gagliano (1970), Danny Breeden (1971), and Pat Bourque (1971–73), a hot hitting prospect with many home runs in the minors who never got a chance with the Cubs; he later played a couple of seasons in the AL.

The revolving door at #19 continued with the player acquired in trade for Bourque, Gonzalo Marquez (1973–74). After Manny Trillo departed, it continued with Pat Tabler (1981–82); Dave Owen (1983–85), who also had a signature career moment and became the answer to a trivia question when he singled in the winning run in the 11th inning of the “Sandberg Game” on June 23, 1984, one of only 27 hits he had in his career; Curtis Wilkerson (1989–90); Hector Villanueva (1991–92), a big bull of a man who had tremendous power (25 HR in 473 career AB) but no position; they tried him at catcher but he should have been a DH; Kevin Roberson (1993–95); Brooks Kieschnick (1996–97), who later in his career pulled a Jeffcoat while with the Brewers and put up a couple of decent years as a middle reliever/pinch hitter; Jason Hardtke (1998); Curtis Goodwin (1999); Jose Molina (1999); Gary Matthews Jr. (2001); and the Cubs’ first Korean-born player, Hee Seop Choi (2002–03), whose ascent through the minor leagues prompted the Cubs to let Mark Grace walk via free agency. Management hoped Choi would be the club’s first baseman for years to come, but after a frightening collision with Kerry Wood chasing a popup on June 7, 2003 (Choi was taken off the field in an ambulance, the only time an ambulance has ever been driven onto the field at Wrigley), he was never quite the same player. His biggest contribution to the Cubs was being shipped to Florida for Derrek Lee.

Matt Murton (2005–08) was a popular outfielder nicknamed “Orange Guy” because of the color of his hair. Unfortunately his performance never lived up to his popularity, and after two years of less than outstanding play he was sent to Oakland in the Rich Harden deal. Following Murton, the #19 revolving door began spinning again with Tyler Colvin (2009), Bobby Scales (2010), Rodrigo Lopez (2012), Nate Schierholtz (2013–14), Dan Straily (2014) and Jonathan Herrera (2015). Herrera, at least, added some levity to the great 2015 Cubs playoff season by his invention of the “rally bucket,” an empty bubble-gum bucket that he’d place over his head late in games when the Cubs were trailing.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #19: Elder White (1962). White, whose name makes him sound like a deacon in the Mormon Church, was one of three Cubs to wear #19 in the 1962 season, when the Cubs used 43 different players en route to a 103-loss year, the worst in team history. White was the Opening Day shortstop—with Ernie Banks having moved to first base, it was the first time since 1953 that anyone but Ernie had played shortstop on Opening Day—but White quickly played himself to the bench, starting only 13 more games and batting .151 in 53 at-bats before vanishing forever from the major leagues.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #19: Bill Henry (1958). Henry, who also wore #37 in 1959, had two solid seasons as a Cubs reliever and then, because management apparently thought the team needed more power (they didn’t; they ranked third in the league in ’59 with 163 homers), traded him to Cincinnati for Frank Thomas (the “other” Frank Thomas, not the White Sox/A’s DH). Thomas hit 286 HR in a 16-year career, mostly with Pittsburgh, yet only 23 in a year and a fraction of another with the Cubs. Henry, meanwhile, made the All-Star team in his first year as a Red and helped lead them to the NL pennant in 1961.

Numbers Not Off Their Backs: Since 1932 Edition

1. Home games played on foreign soil. On March 30, 2000, the Cubs lost to the Mets, 5–1, in 11 innings at the Tokyo Dome; the Cubs had also won the previous day in Tokyo with the Mets serving as home team, 5–3.

2. The number of times shortstop Billy Jurges was shot by spurned girlfriend Violet Popovich Valli in 1932; he returned to the Cubs two weeks later, while she received a nightclub contract as a singer.

3½. Innings the Cubs and Phillies played in the first night game at Wrigley Field before the game was rained out on August 8, 1988.

4. Major league starts it took Cubs rookie Burt Hooton to toss a no-hitter; the victim was Philadelphia, April 16, 1972.

7. Total wins as a Cub, against 19 defeats, by Ernie Broglio after coming from St. Louis in the deal for twenty-four-year-old future Hall of Famer Lou Brock.

20. Strikeouts by Kerry Wood in just his fifth major league start, tying the big league record for most K’s in a game.

22. Runs scored against the Phillies at Wrigley on May 17, 1979. And the Cubs still lost by one!

36. Years between no-hitters by the Cubs. After the near perfect game by Milt Pappas (he issued a walk on a close 3–2 pitch with two outs in the ninth) against the Padres on September 2, 1972, Carlos Zambrano next threw one against Houston in Milwaukee (moved there because of a tropical storm in Texas) on September 14, 2008.

60.75. Sammy Sosa’s average annual home run production between 1998–2001.

123. Consecutive errorless games by Ryne Sandberg at second base in 1990.