#26: BILLY WILLIAMS EVERY DAY

| ALL-TIME #26 ROSTER | |

| Player | Years |

| Newt Kimball | 1938 |

| Clay Bryant | 1940 |

| Lou Novikoff | 1941 |

| Charlie Brewster | 1944 |

| Jimmie Foxx (player-coach) | 1944 |

| Hank Borowy | 1945–48 |

| Monk Dubiel | 1949–52 |

| Bill Moisan | 1953 |

| Sheldon Jones | 1953 |

| Bob Thorpe | 1955 |

| Moe Drabowsky | 1956–58 |

| Billy Williams (player and coach) | 1961–74, 1980–82, 1986–87, 1992–2001 |

| Larry Biittner | 1976–79 |

| Fritzie Connally | 1983 |

While many baby-boomer era Cubs fans idolized Ernie Banks for his production and sunny personality, or Ron Santo for his passion for the game and great play at third base, Sweet Swingin’ Billy Williams got far less notice while putting up a Hall of Fame career. He went about his job quietly, consistently producing year in and year out while playing in 1,117 consecutive games from 1963 through 1970. He played in 150 or more games for 12 straight seasons, 1962–73, and, along with Santo, is the co-club record holder for games in a season, 164 (all the decisions plus two tie games in 1965).

Billy was installed as the regular left fielder in 1961, at the age of twenty-three. The Cubs were terrible—they finished 64–90 and would have finished last if not for the even more awful Phillies—but Billy blossomed. He hit .278/.338/.484 with 25 homers and 86 RBI, and was named National League Rookie of the Year, the first of two straight Cubs to win the award (the late Kenny Hubbs following in 1962).

The following year Billy began a remarkable streak—no, not his consecutive game streak, which would come later, but a series of twelve straight years in which he would drive in no fewer than 84 runs, and in ten of those years (all except 1967 and 1973) he had 90 or more. He began the streak during the worst period for offense since before World War I.

He was primarily a left fielder, although in 1965 and 1966 he played mostly in right field. He didn’t really have the arm or the range to cover right—he played there mostly because the other options, guys like Doug Clemens, Don Landrum, and Byron Browne were even worse—so in ’67 he moved back to left field, to stay there until an ill-advised attempt to make him a first baseman in 1974.

On September 21, 1963, Billy sat out an otherwise ordinary 4–0 loss to the Braves. Warren Spahn was pitching, so perhaps head coach Bob Kennedy sat him against “a tough lefty.” It would be the last game he would miss for nearly seven years. The next day, Billy began a consecutive-game playing streak that lasted until September 3, 1970, when Billy told manager Leo Durocher he wanted to end the streak. It had gotten too big for him, he thought, and he didn’t want the added pressure as he approached what was then the second-longest streak in history, Everett Scott’s 1,307 games (and after his streak had been kept going the previous year in mid-June with three token pinch-hitting appearances after he had suffered a minor injury in Cincinnati). Billy’s National League record was broken by Steve Garvey on April 16, 1983. Interesting note: Had Williams not skipped that September 21, 1963 game, his streak would have been 166 games longer (1,283), as he had played in all 155 previous games that year, and the final 11 games of 1962. And it would still be the NL record, since Garvey’s streak stopped at 1,207 straight games when a broken thumb forced him to miss the last two months of ’83.

One of Billy’s biggest disappointments was never winning an MVP award, even in his two biggest years, 1970 and 1972. In 1970, a hitters’ year, he hit .322/.391/.586, with 42 home runs and 129 RBI. He led the National League in runs, hits (tied with Pete Rose), and total bases, but lost the MVP to Johnny Bench, who had a spectacular year for the eventual pennant-winning Reds. Two years later, Billy won the batting title,with a .333 average, becoming the first Cub to do so since Phil Cavarretta in 1945. The rest of his line included a .398 on base percentage, a .606 slugging percentage, and finishing second in RBI (by two) and third in homers (by three), but Bench again won the MVP for the NL champions. That’s about as close as anyone has come to winning the Triple Crown in the National League in the last eighty years. Billy also led the league in 1972 in total bases, slugging percentage, OPS, and extra-base hits. During one twelve-game stretch in mid-July 1972, he went 28-for-53 (.528) with six homers and 17 RBI.

Rarely flashy and always classy, Billy Williams did not miss a game for eight seasons.

Seven years after he retired, Billy was invited to play in a pre All-Star Game event, an AL vs. NL Old-Timer’s game, at the old Comiskey Park, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first All-Star game in 1933. At age 44, still in playing-shape trim, he was one of the youngest players in that game. And early in that three-inning affair, he came up to bat against Hoyt Wilhelm and promptly hit a monstrous home run into the right-field upper deck.

Wilhelm, a Hall of Famer in his own right, was nearly sixty-one years old at the time, but Billy’s home run became the talk of many national sportswriters covering the event. It also got people remembering how good a hitter Billy was, and some of the writers who subsequently voted for him for the Hall of Fame said it was a factor in their votes and his eventual election. His Hall vote totals—twenty-three percent in 1982 and forty percent in 1983—steadily climbed after that, and he was elected to Cooperstown in 1987 (after missing by only four votes in 1986). On August 13, 1987 the Cubs retired #26 in Billy’s honor. Though underrated for most of his career—and often an afterthought compared to NL outfielders Aaron, Mays, and Clemente (he only was chosen to play in seven All-Star Games for the NL; that trio was selected a total of sixty-three times!)—Billy got support at the perfect time.

Billy coached for the Cubs in varying capacities (mainly as first base and bench coach) for fifteen seasons after his retirement, also spending three years in Oakland as coach with the A’s in the mid-1980s. (He had played his last two seasons as a DH for Oakland, appearing in his lone postseason series and, sadly, going hitless as the A’s were swept in the last ALCS of their dynasty.) The thirty-one seasons in which he wore the Cubs uniform exceed that of any other single individual; Billy participated in over 5,000 Cubs games as a player or coach. And in each and every one of them, he conducted himself with class, dignity, and grace.

In the Wrigley era, Cubs ownership and management didn’t believe in retiring numbers, though they never reissued Ernie Banks’s #14 after his retirement in 1971. Strangely, Williams’s #26 didn’t get the same treatment—possibly because he didn’t finish his career as a Cub, as Banks did. Two years after Billy was traded to the A’s, #26 was issued to Larry Biittner (1976–79). The man with the strangely-spelled surname was a capable fourth outfielder/backup first baseman, but it was still odd to see Billy’s #26 worn by this total stranger to Cubs fans. Biittner became a familiar face at Wrigley, even if his two main claims to fame as a Cub came in incidents he’d probably wish be forgotten. On July 4, 1977, in the first game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field against his former team, the Cubs trailed 11–2 in the top of the eighth inning. Manager Herman Franks, trying to save his bullpen with the temperature approaching 100 degrees, sent Larry in to pitch with two out and a runner on second. Let’s just say he wasn’t very good: Biittner allowed five hits, a walk, three home runs, and was warned by plate umpire Terry Tata for supposedly throwing at the head of Expos outfielder Del Unser. Biittner threw up his arms as if to say, “Throwing at him? Me? I couldn’t get the ball near the plate if I tried!” He did register three strikeouts and the eternal memories of Cubs fans, who were treated to this WGN-TV graphic upon his entry to the game: “LARRY BIITTNER: PIITCHING.”

Two years later, on September 26, 1979, Biittner was playing right field, in a meaningless game between the fifth-place Cubs and the sixth-place Mets. In the fourth inning, Mets outfielder Bruce Boisclair hit a ball to right and Biittner took off after it, his cap flying off as he pursued the flying sphere, which dropped in for a double—and promptly landed under the cap. He frantically looked around for it as bleacher fans yelled at him, “Hat! Hat!” Biittner located the ball and threw Boisclair out trying for third base.

When Billy Williams returned to the Cubs as a coach in 1980, Biittner switched to #33.

Many years before either Williams or Biittner donned #26, Hank Borowy (1945–48) sported the number. The Cubs bought Borowy, who had World Series experience, from the Yankees on July 27, 1945, and he went 11–2 down the stretch to lead the Cubs to the pennant. Borowy, who finished sixth in the 1945 NL MVP voting, teamed with Claude Passeau, Hank Wyse, and Ray Prim to form the league’s top rotation. Borowy became the first pitcher to have a 20-win season split between the two leagues, a feat later matched by Rick Sutcliffe in the 1984 NL East title year. In the World Series, Borowy shut out the Tigers in the opener but did not pitch again until Game 5, which he lost. He tossed the last three innings in relief the next day as the Cubs won in twelve innings. Although worn out, Borowy started Game 7 two days later. He was knocked out in the first inning. You couldn’t blame him. (Some would fault manager Charlie Grimm.) The Cubs hoped that the twenty-nine-year-old Borowy would remain a solid starter for them for years to come, but he developed arm trouble and lasted only three more years in Chicago before bouncing around to the Phillies and Tigers.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #26: Fritzie Connally (1983). In addition to the fact that “Fritzie” isn’t a very good name for a baseball player, Connally wasn’t a very good baseball player. The last Cub to wear #26 before it was rightfully given to Billy Williams for good, he went hitless in 10 at bats wearing the number. Connally was part of the multi-team deal after the 1983 season which helped bring Scott Sanderson to the Cubs.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #26: Moe Drabowsky (1956–58), one of only four major leaguers born in Poland, was a bonus baby who became the Cubs’ top pitcher in his first full season at age twenty-one. Drabowsky led the 1957 Cubs in starts, complete games, innings, strikeouts, and ERA. But he had a reputation as a practical joker, and so the straight-laced 1950s era Cubs, never known for letting baseball talent interfere with getting rid of players who didn’t fit the mold, sent him to the Milwaukee Braves with Seth Morehead for Andre Rodgers and infielder Daryl Robertson on March 31, 1961. This began an odyssey that saw Drabowsky play for eight organizations, including Baltimore twice, where he became a solid reliever and a key contributor to two Orioles world champion teams in 1966 and 1970, plus stints with both the Kansas City A’s and Royals. Drabowsky also donned #39 for the Cubs in 1959 and 1960.

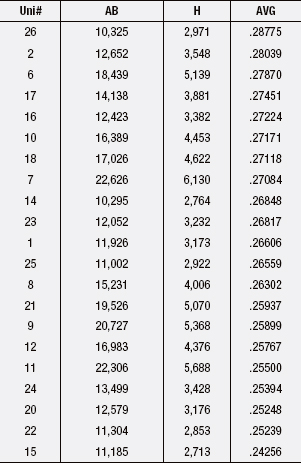

The Best-Hitting Cubs Number

So #7’s big lead in all-time Cub at-bats (22,626) and hits (6,130) leaves an opening for other numbers that have seen a little less action to snatch away the best batting average, just as Rick Monday grabbed that flag away from those two seditious punks who would have burned it in the Dodger Stadium outfield back in 1976. Nothing quite as serious here, though it is kind of ironic that Monday wore #7—and it is kind of spooky that his Cubs batting average of .270 is the same as #7’s.

Anyway, without further ado, the best-hitting Cubs number ever is…#63. What? Yes, #63 is the owner of a 1.000 average earned in a single at-bat in a blowout loss in Milwaukee on June 1, 2014. Trailing 9–0 in the seventh, the last-place Cubs let Brian Schlitter be a hitter. The reliever’s line single was the second hit of the day off Kyle Lohse and the first and only try for #63. You won’t find it on the list below, though. Nor will you find #62, with its .333 average (in six at bats); or even the .287 mark in 1,200 at-bats for #53. On the other end, the worst-hitting Cubs number to have seen an at-bat is #60, with a .000 average. But a number can always hit its way out, like #54 did. Darnell McDonald’s final career flourish in 2013 was a .302 average in minimal duty to lift #54 on his shoulders: from a stupefying .070 average (in 114 at-bats) all the way to .138 and out of last place. That’s more than the 96-loss team McDonald played for could say.

To keep it fair, we’ve held the minimum to 10,000 at-bats for a uniform number to qualify for this list. (That’s about 120 at-bats per year since the Cubs started wearing uniform numbers in 1932.) The payoff is that #26 takes the top all-time spot among the 21 numbers to reach the five-digit mark in at-bats. It’s fitting that the classy Billy Williams, who owns 82 percent of the career at-bats for #26, gets this honor. For those who are still biitter that Larry Biittner was assigned the number after Williams left, #26 wouldn’t have reached 10,000 at-bats without the ex-Expo. And .28775 (oh, let’s round it to .288) for #26 may forever hold the top honor since the number is now retired for Williams. It also makes up for the somewhat random results that follow.