#27: THE VULTURE AND THE TOOTHPICK

| ALL-TIME #27 ROSTER | |

| Player | Years |

| Bobo Newsom | 1932 |

| Gene Lillard | 1939 |

| Eddie Waitkus | 1941 |

| Lennie Merullo | 1941 |

| Russ Meers | 1941 |

| George Hennessey | 1945 |

| Walter Signer | 1945 |

| Al Glossop | 1946 |

| John Ostrowski | 1946 |

| Dutch McCall | 1948 |

| Bill Serena | 1949 |

| Cal McLish | 1951 |

| Jim Brosnan | 1954 |

| Sam Jones | 1955–56 |

| Dale Long | 1957 |

| Dolan Nichols | 1958 |

| Jim Marshall | 1958 |

| Danny Murphy | 1962 |

| Don Landrum | 1962–64 |

| Doug Clemens | 1964–65 |

| Bob Raudman | 1966–67 |

| Clarence Jones | 1967 |

| Phil Regan (player) | 1968–72 |

| (coach) | 1997–98 |

| Jim Tyrone | 1972, 1974–75 |

| Pete Reiser (coach) | 1973 |

| Champ Summers | 1975–76 |

| Joe Wallis | 1977 |

| Mike Vail | 1978–80 |

| Hector Cruz | 1981 |

| Mel Hall | 1982–84 |

| Thad Bosley | 1984–86 |

| Rolando Roomes | 1988 |

| Derrick May | 1990–94 |

| Willie Banks | 1995 |

| Todd Zeile | 1995 |

| Doug Jones | 1996 |

| Scott Sanders | 1999 |

| Corey Patterson | 2000 |

| Joe Girardi | 2001–02 |

| Damian Miller | 2003 |

| David Kelton | 2004 |

| Craig Monroe | 2007 |

| Casey McGehee | 2008 |

| Sam Fuld | 2009 |

| Casey Coleman | 2010–12 |

| Phil Coke | 2015 |

| Taylor Teagarden | 2015 |

| Austin Jackson | 2015 |

It is one of the saddest moments in modern Cubs history. On September 7, 1969, the Cubs, having lost three in a row but still maintaining a 3½ game lead in the NL East, led the Pirates 5–4 in the ninth inning at Wrigley Field. A win would have stanched the losing streak and righted what many worried was a sinking ship. But on a two-out, two-strike pitch, Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell launched a ball onto Sheffield Avenue, tying the game, and the Cubs eventually lost, 7–5 in 11 innings. The losing streak reached eight and the Cubs fell out of first place, never to return. The homer was hit off closer Phil Regan (1968–72). Regan was acquired in early 1968 from the Dodgers, where he had picked up the nickname “The Vulture” for “vulturing” wins—four in 1966 alone—by coming into games with leads, blowing them, and then having the Dodgers come back and get him a win.

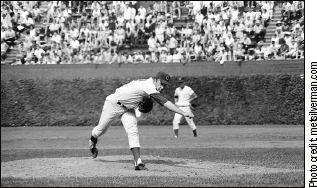

“The Vulture,” Phil Regan got the save this time against the Mets in 1969.

Regan, unlike modern closers, was a workhorse, throwing 127 innings in his first Cubs season and posting 10 wins, 25 saves (leading the NL), and a 2.20 ERA. In ’69, however, gassed from overuse, his ERA ballooned to 3.70. His walks were up and strikeouts down and the Stargell HR led to him being virtually booed out of town, or at least the North Side of town, as he was eventually sold to the White Sox in 1972. Later, he became a college baseball coach and a respected pitching coach for several teams, including the Cubs in 1997 and 1998, serving as Kerry Wood’s first major league pitching coach.

Besides Regan, only one Cub—Derrick May—wore #27 for as many as five seasons (in May’s case, two September callups and three full years, 1992–94). May, son of former big leaguer Dave May and a highly touted first-round draft pick, looked the part of the power prospect: tall and imposing at 6-foot-4, 225. It didn’t take long for the Cubs to recognize that May couldn’t hit left-handed pitching, however, and he was relegated to platoon status. His best Cubs season came in 1993, when he drove in 77 runs, but even then he hit only 10 homers. His lackadaisical performance in the outfield led some fans to nickname him “Derelict May.” He left the Cubs after 1994 and drifted through five more seasons with five more teams: the Brewers, Astros, Phillies, Expos, and Orioles, the same number of clubs his dad played for as a spare outfielder.

In the early years, #27 was a number given to many forgettable players. It began with Bobo Newsom, who later became famous for having several different stints with bad AL teams in St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Washington (All three of which moved, but not because of Bobo). He won 211 major league games, but none of them as a Cub, for whom he threw only one inning in 1932. Several others wore #27 briefly in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, some becoming more famous wearing other numbers: Gene Lillard (1939), Eddie Waitkus (1941—#36 later on), Lennie Merullo (1941—five years wearing #21), Russ Meers (1941), Walter Signer (1945), Al Glossop (1946), John Ostrowski (1946), Dutch McCall (1948), Bill Serena (1949—six seasons in #6), Cal McLish (1951) and Jim Brosnan (1954). Brosnan also wore two future retired numbers, #23 and #42, and, as did many Cubs in that era, had several better seasons elsewhere, in his case in Cincinnati, where he helped the Reds to the NL pennant in 1961 and wrote about the experience in Pennant Race, the followup to his landmark book, The Long Season.

Sam Jones (1955–56) was sort of like a young Nolan Ryan. “Toothpick Sam,” so named because of his build (6-foot-4, 200), threw really hard; he just didn’t always know where it was going. In 1955, his first full major league season, he struck out 198, leading the NL (by 38), but he also walked 185, leading the league (by 77). On May 12, 1955, he threw one of the sloppiest no-hitters in baseball history (and the first by a Cub in thirty-eight years), walking the bases loaded in the ninth inning and then striking out the side. The Cubs tired of Jones’s wildness, and flicked the Toothpick to the Cardinals in an eight-player deal involving no one of lasting baseball significance. Naturally, Jones enjoyed some success in St. Louis, winning 21 games and finishing second in the 1959 Cy Young voting. As far as the whole career goes, though, not winning a Cy Young was about all Toothpick and the Ryan Express had in common.

Danny Murphy became the youngest Cub since the 19th century when he debuted at age seventeen on June 18, 1960, wearing #42. He was just past his eighteenth birthday when he became the youngest Cub to collect a homer, in an 8–6 loss to Cincinnati on September 13. The next year, switching to #27, he became the youngest in club history to make the Opening Day roster, but his promise as an outfielder faded. It wasn’t until ’69 that he reappeared in the bigs, on the other side of town, as a pitcher. He went 4–4 with a 4.66 ERA over two seasons as a White Sox reliever.

After that, various and sundry outfielders wore #27 through the 1970s and 1980s. Champ Summers (1975–76) had a great baseball name but not that much of a career; his first major league homer was perhaps his most memorable—a pinch-hit grand slam on August 23, 1975. The Cubs had back-to-back six-run innings that day, but lost to Houston, 14–12. Sigh. The rumba line continues: Joe Wallis (1977); Mike Vail (1978–80); Hector Cruz (1981); Mel Hall (1982–84), who did have promise and a decent major league career, but his best contribution to the Cubs was being included in the Rick Sutcliffe trade; Thad Bosley (1984–86), better known after his baseball career as a gospel singer; and Rolando Roomes (1988), one of only four major leaguers born in Jamaica (Chili Davis, Devon White, and Justin Masterson are the others, if you want some good bar-bet trivia).

Recent years have seen catchers, “more famous under other number” guys, and mediocre pitchers sport #27: Willie Banks (1995), Doug Jones (1996), Scott Sanders (1999; no one could confuse him with former Cub Scott Sanderson, either by number—Sanderson wore #21 and #24—or by performance; Sanders put up a 5.52 ERA in 67 games), Corey Patterson (2000, better known as a #20, this was his first Cubs number), Joe Girardi (2001–02, this was Joe’s second go-around with the Cubs—he wore #7 the first time); Damian Miller (2003, the glue of the NL Central champs that year); David Kelton (2004); Craig Monroe (2007); and Sam Fuld (2009).

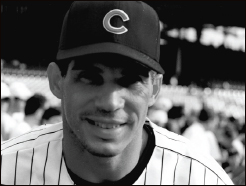

Joe Girardi is better known as a manager elsewhere, but he went to Northwestern, started his pro career in his hometown of Peoria, and was a Cub—twice!

Casey at the bat found #27, if only in name: Casey McGehee (2008) and Casey Coleman (2010–12). Mighty Casey(s) indeed struck out. McGehee, pounced “McGee,” fanned eight times in 24 at-bats as a September ’08 callup before the Brewers grabbed him off waivers. Coleman struck out in his big chance in the Cubs rotation, going 3–9 with a 6.40 ERA in 17 starts in 2011.

Though 2015 was an invigorating year for the Cubs, #27 turned into the pause that refreshes: lefty Phil Coke put on the number, soon followed by catcher Taylor Teagarden. Coke turned flat and was released by three teams in 2015. The Teagarden party was brief, though he did get a game-winning hit off the bench against flame-throwing Aroldis Chapman, then of the Reds, in late July. The third #27 in ’15 was Austin Jackson, brought over from Seattle at the August 31 deadline. The free-agent-to-be played all three outfield positions in Chicago during the final month, but he did not do much to dislodge anyone from the outfield jam come playoff time. The one-time emerging star looked like a fourth outfielder at age 29. He batted eight times with zero hits in three postseason rounds. He tried his luck on the other side of Chicago in 2016.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #27: George Hennessey (1945). Hennessey pitched in five games for the 1937 St. Louis Browns, who went 46–108; five more for the 1942 Phillies, who went 42–109, and then, for some reason, the 1945 pennant-bound Cubs decided to sign him at age thirty-seven. He pitched in two games and was shipped to the minors on June 13, never to return. We know there was a war on, but geez, no other 4-Fs were around? Now you know he wore a Cubs uniform in a pennant-winning year—and not many players have.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #27: Todd Zeile (1995). Zeile could win the “Guy You Never Thought of As” award for quite a few teams. After hitting 75 homers over six years in St. Louis, he was traded to the Cubs on June 16, 1995, in a year when the Cubs thought that adding just one more power hitter might help them to the postseason. Zeile hit just .227 with nine dingers and made his disdain for Cubdom well known. He was allowed to depart as a free agent, and over the next nine years his baseball odyssey took him to the Phillies, Orioles, Dodgers, Marlins, Rangers, Mets, Rockies, Yankees, Expos and finally back to the Mets for a curtain call (he homered in his last at-bat). If Zeile had ended his playing days with a team he’d never played for previously—and by that point in his itinerant career those teams were in short supply—he would have tied the then-record for most teams played in a career: twelve, set by Mike Morgan, the guy the Cubs traded to get Zeile in 1995.

Numbers Off to the Triple

While #7 has collected more triples than any other uniform number in Cubs history, the bearers of that number aren’t in the same ballpark with the unnumbered sluggers of days gone by who made the triple their own. Before uniform numbers, when ballparks were bigger and no one posed to watch their deep drives, the triple was the power stat of the day. The four Cubs on the career list with triple-digit triples—Jimmy Ryan (142), Cap Anson (124), Frank “Wildfire” Schulte (117), and Bill Dahlen (106)—collected just one triple among them while calling Wrigley Field home. Schulte, an outfielder in the Cubs’ glory days of the early twentieth century, outlasted Tinker, Evans, and Chance, playing at Wrigley the year the Cubs moved in, in 1916. That was still sixteen years shy of the introduction of uniform numbers at Wrigley.

With numbers, it doesn’t quite add up. Ernie Banks had 90 of the 94 triples at #14, keeping it way down on this list; Phil Cavarreta had 99 three-baggers, but the total is split among four numbers (#3, #4, #43, #44), with only half of those numbers making the top twenty.

| Uni # | Triples |

| 7 | 190 |

| 11 | 163 |

| 10 | 144 |

| 9 | 139 |

| 6 | 131 |

| 18 | 124 |

| 21 | 121 |

| 17 | 111 |

| 4 | 110 |

| 1 | 109 |

| 12 | 108 |

| 2 | 107 |

| 23 | 105 |

| 8 | 104 |

| 24 | 102 |

| 5 | 94 |

| 14 | 94 |

| 26 | 93 |

| 20 | 92 |

| 44 | 76 |