#28: CLOSING TIME

| ALL-TIME #28 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Jack Russell | 1938–39 |

| Bobby Sturgeon | 1940–42 |

| Russ Meyer | 1947–48 |

| Jim Willis | 1953–54 |

| Hal Rice | 1954 |

| Lloyd Merriman | 1955 |

| Glen Hobbie | 1957–58 |

| Bob Will | 1960–63 |

| Billy Ott | 1964 |

| Lee Gregory | 1964 |

| Roberto Pena | 1965–66 |

| Marty Keough | 1966 |

| Jim Hickman | 1968–73 |

| Ron Dunn | 1974 |

| Adrian Garrett | 1975 |

| Joe Wallis | 1975–76 |

| Jerry Martin | 1979–80 |

| Steve Henderson | 1981–82 |

| Henry Cotto | 1984 |

| Chris Speier | 1985–86 |

| Luis Quinones | 1987 |

| Mark Grace | 1988 |

| Mitch Webster | 1988 |

| Mitch Williams | 1989–90 |

| Ced Landrum | 1991 |

| Kal Daniels | 1992 |

| Randy Myers | 1993–95 |

| Pedro Valdes | 1996, 1998 |

| Roosevelt Brown | 1999–2001 |

| Mark Bellhorn | 2002–03 |

| David Kelton | 2003 |

| Todd Hollandsworth | 2004–05 |

| Michael Restovich | 2006 |

| Gerald Perry (coach) | 2007–09 |

| Jeff Baker | 2009–11 |

| Paul Maholm | 2012 |

| Michael Bowden | 2012–13 |

| Chris Coghlan | 2014 |

| Kyle Hendricks | 2014–15 |

Of the thirty-eight players and two coaches who have worn #28, only ten have been pitchers. And three of those hurlers, Paul Maholm (2012), Michael Bowden (2012–13), and Kyle Hendricks (2014–15)—have donned the number in the past five years. But two #28s have combined for 164 saves wearing blue pinstripes. And all of those came over five years in the 1980s and 1990s.

Randy Myers’s 53 saves in 1993 established a National League record that stood until John Smoltz broke it with 55 in 2002, and Mitch Williams’s 36 saves in 1989 helped the Cubs win the NL East title. Those totals still rank first and sixth on the all-time Cubs single season list. (And the 38 saves by Myers in strike-shortened 1995 is tied with Carlos Marmol’s 2010 total for third on that list.)

Williams was known as “The Wild Thing” because his antics and his penchant for throwing pitches with an unknown destination were similar to Charlie Sheen’s character Rick “Wild Thing” Vaughn in Major League, which came out the year Williams came to the Cubs. Williams came from the Rangers in the eight-player deal that sent Rafael Palmeiro to Texas. Palmeiro, a singles hitter at the time (he had hit only eight home runs in nearly 600 at-bats in 1988), put up ten 30-homer seasons after leaving the Cubs and before becoming discredited for testing positive for steroids. Without Williams’s flamboyance and baseball smarts (on September 11, 1989, he picked off Expos rookie Jeff Huson to end a Cubs victory, getting a save without throwing a pitch), they wouldn’t have won the division. In the NLCS, Williams gave up the series-winning, two-run single to Will Clark, an eerie precursor to his serving up the World Series-winning homer to Joe Carter four years later as a Phillie.

The Cubs dealt Williams to Philadelphia the day before Opening Day 1991, for mediocre relievers Bob Scanlan and Chuck McElroy. But Cubs fans will always remember the man who was described by his teammate Mark Grace as “pitching like his hair was on fire.”

Just looking at a picture of Mitch Williams, one thought comes to mind: “The count is already 2-0!”

Myers had been best known in Cubs history for serving up the first walkoff of Mark Grace’s career on July 30, 1989, in a key game in that playoff year, while Myers was a Met. The next year, Myers became one of Lou Piniella’s “Nasty Boys” with the world champion Reds. Signed as a free agent by the Cubs before the 1993 season, Myers paid immediate dividends in Chicago by setting the NL record for saves, 53, although that Cubs team finished far out of playoff contention. It was on August 15 of that year that the Cubs marketing department arranged to give fans posters of the then-popular Myers. Unfortunately, Myers chose that day to give up homers to Barry Bonds and Matt Williams, breaking a 7–7 tie in the 11th inning. Bleacher fans littered the field with the posters, prompting the Cubs, for several years afterward, to not give out promotional items in the bleachers until after the game.

Myers was involved in another weird brouhaha in the second-to-last game he pitched in a Cubs uniform. On September 28, 1995, with the Cubs desperately trying to hold on in the very first wild-card race, Myers gave up a crucial eighth-inning longball to James Mouton of the Astros. As manager Jim Riggleman was taking Myers out of the game, a disgruntled fan ran out on the field. Myers responded with what shortstop Shawon Dunston later termed “one of those martial arts moves,” and pinned the assailant to the turf until authorities hauled him away. This incident did have a happy ending—the Cubs wound up bailing Myers out by winning the game, coming from behind in the eighth, tenth and eleventh innings—but the Cubs still failed to capture the Wild Card.

Only one other Cub wore #28 for more than four seasons, and his gentle nature was quite the opposite of the volatile Williams and the hard-throwing Myers. Jim Hickman, known as “Gentleman Jim,” had crossed paths with the Cubs in a memorable way while a Met in 1963. Mets pitcher Roger Craig had lost 18 consecutive games, then an NL record, but on August 9, Hickman hit a walkoff grand slam at the Polo Grounds off Cubs reliever Lindy McDaniel, winning the game for Craig and the Mets, 7–3. After a stint with the Dodgers, he was dealt to the Cubs on April 23, 1968 (along with reliever Phil Regan). Hickman sat mainly on the bench until Leo Durocher made him the team’s primary right fielder in spring training of 1969. He hit a then-career high of 21 homers in 338 at-bats, tying Billy Williams for third best on the club, although Williams batted nearly twice as many times.

The following year, playing every day splitting time between first base and the outfield, Hickman had a career year, hitting .315 with 32 homers and 115 RBI. This performance earned him his first and only invitation to the All-Star team,and an eighth place finish in the NL MVP voting. In that All-Star Game, Hickman played a role in one of the Midsummer Classic’s most memorable moments, as his single drove in the winning run in the twelfth inning. That runner was Pete Rose, whose full-speed crash into Indians catcher Ray Fosse sent the latter to the hospital and perhaps ruined a career.

From Jack “Not A Terrier, A Pitcher” Russell (1938–39) to Bobby Sturgeon (1940–42) to Russ Meyer (1947–48) to Jim Willis (1953–54) to Hal Rice (1954) to Lloyd Merriman (1955) to Glen Hobbie (1957–58) to Bob “No Relation To George” Will (1960–63), the early years of Cub #28s were forgettable, though Hobbie did have two 16-win seasons wearing #40 in 1959 and 1960.

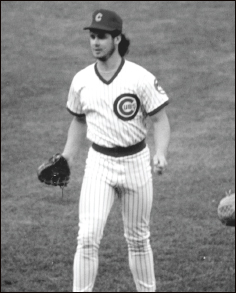

In the years post-Hickman, #28 was mostly an outfielder’s number, with the notable exceptions of Williams and Myers. This list of outfielders, though, would frighten no one, except perhaps a Cubs manager trying to make out a lineup card: Ron Dunn (1974), Joe Wallis (1975–76), Jerry Martin (1979–80), Steve Henderson (1981–82), Henry Cotto (1984), Mitch Webster (1988), Ced Landrum (1991), Pedro Valdes (1996, 1998), Roosevelt Brown (1999–2001), David Kelton (2003), Todd Hollandsworth (2004–05), and Michael Restovich (2006); Restovich was considered for the “obscure” nod, because he had had a great spring training and was pushed by GM Jim Hendry as a possible right field platoon partner for Jacque Jones, who never could hit lefties. But Dusty Baker refused to play him; Restovich appeared in ten games but never started, and eventually he was sent back to the minors.

Mitch Webster looks like he’s waiting for a bus out of Astroturf City.

A couple of twenty-first century infielders took #28 in different directions. Jeff Baker (2009–12) seemed like he had power—maybe because he came over from Colorado—but he hit just 15 homers in parts of four seasons as a Cub. Mark Bellhorn (2002–03) on the other hand, arrived from Oakland with no history of power, real or imagined. That changed in 2002, when Bellhorn hit 27 home runs. Two of those 27 round-trippers came on August 29, when Bellhorn connected from both sides of the plate in the fourth inning of a 13–10 Cubs win over the Brewers, becoming only the second player in history to perform that feat in one inning. He also drew 76 walks that year, but drove in just 56 runs and fanned 144 times. He was traded to Colorado in 2003, but he emerged on the national scene a year later playing in his native Boston. Mahk Bellhown played a pivotal role in helping the Red Saux win the 2004 World Series.

There are two final #28 oddities. Mark Grace’s #17 is still worn by fans who bought his jersey when he was a Cub for thirteen seasons from 1988 to 2001. But Grace was issued #28 when he was called up on May 2, 1988 and wore it for a three-game series in San Diego. Grace switched to #17 when the Cubs returned home on May 6 in honor of his first base idol, Keith Hernandez. Grace didn’t win eleven straight Gold Gloves like his hero did, but he did receive the award four times in five years and had a Hernandez-esque, built-for-doubles swing that made him an idol at his park.

On May 3, 2014, Chris Coghlan was recalled from Iowa and placed on the 25-man roster. He was issued uniform #28 and was on deck, waiting to pinch-hit for pitcher Brian Schlitter, but Mike Olt made the last out of the inning. Coghlan never did play in that game, though, and when he made his Cubs debut as a pinch-hitter the next day, he was wearing #8, in honor of Andre Dawson, who had helped mentor him when both were in the Marlins organization.

The Cubs don’t officially recognize Coghlan as ever wearing #28, since he didn’t appear in a game in that number. But since he was on the active roster wearing that number and two co-authors of this book were at the May 3 game to witness Coghlan wearing it, we’re going to call it official here. You might say we wrote the book on Cubs uniform numbers.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #28: Lee Gregory (1964). Gregory, acquired before the 1964 season for another obscure reliever, Dick LeMay, pitched briefly for the Cubs in April, and returned in late July, generally performing mop-up duty in blowouts. He appeared in eleven games, all losses, and the Cubs lost those eleven games by a combined score of 94–30. The Fresno State graduate left the majors and returned to Fresno, where he still lives.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #28: Kal Daniels (1992). Daniels, whose real given name was Kalvoski, had hit 100 homers by age twenty-eight when, on June 27, 1992, he was acquired by the Cubs from the Dodgers for a minor leaguer. Management hoped his left-handed power would solidify Chicago’s left-field problem for years to come. Instead, Daniels moped because he wasn’t starting every day; he played in 48 games, starting only 28 of them, hitting four homers before being released at the end of the 1992 season, his last in the majors.

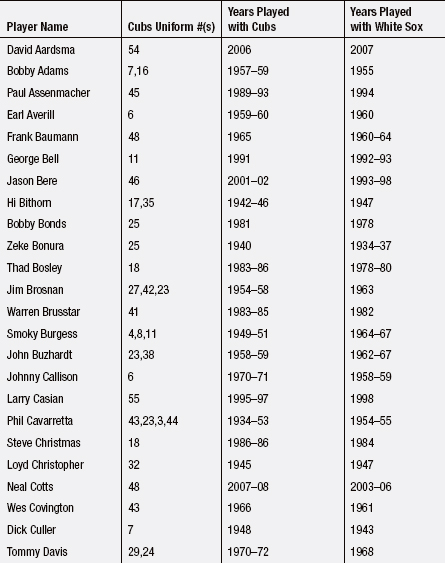

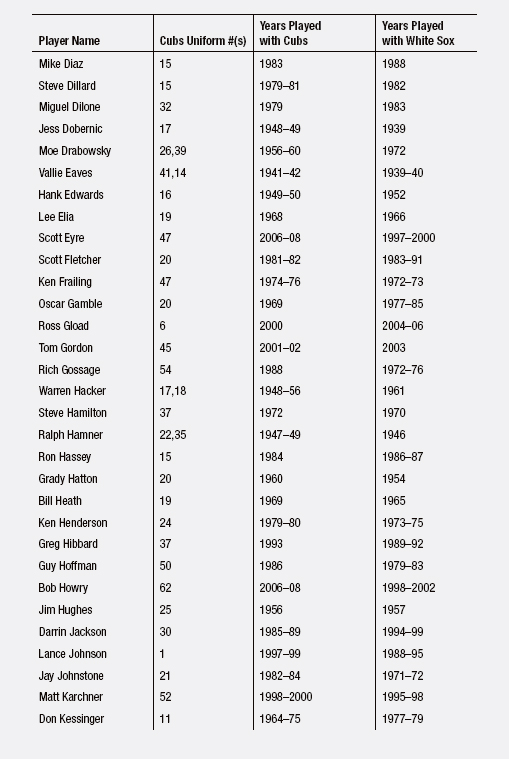

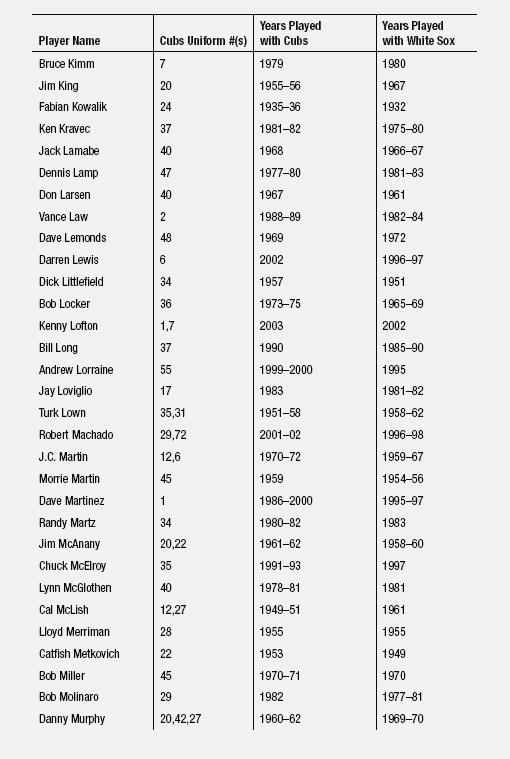

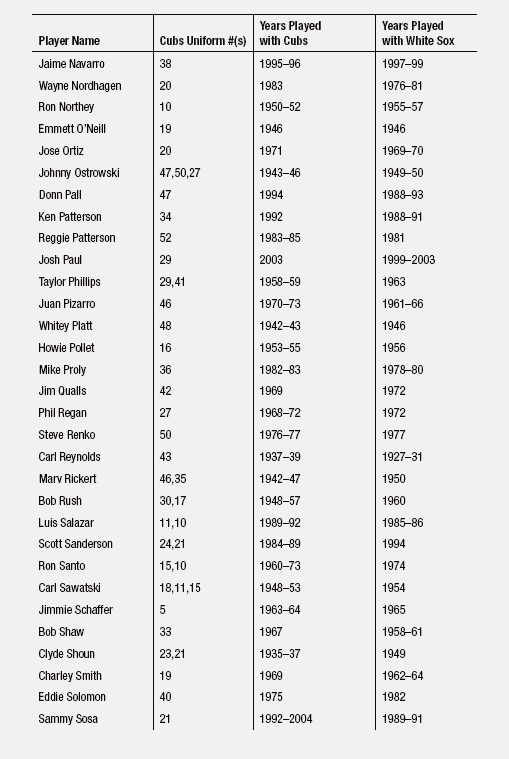

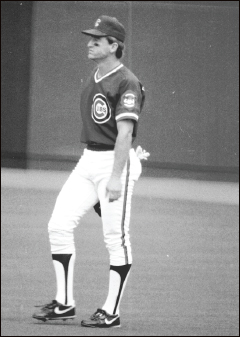

North Side, South Side

There have been 129 players who have worn numbers for both the Cubs and White Sox during their careers, from 1932 through 2008. Many have seen distinguished service with the Cubs and had short stays on the South Side—Ron Santo comes to mind, regrettably. Others have worn the Pale Hose for several years and stopped in at Wrigley Field for a brief appearance. Both Hall of Famers on this list—Hoyt Wilhelm and Rich Gossage (both also on the short list of relievers in Cooperstown)—fit this latter category. There are far more who had short stays on both sides of town.