#38: Z!

| ALL-TIME #38 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Charlie Grimm (coach) | 1941 |

| Kiki Cuyler (coach) | 1941–42 |

| Dick Barrett | 1943 |

| Mickey Livingston | 1943 |

| Garth Mann | 1944 |

| Mack Stewart | 1944–45 |

| Johnny Moore | 1945 |

| Ray Starr | 1945 |

| Bobby Sturgeon | 1946 |

| Russ Meyer | 1946 |

| Bob Zick | 1954 |

| Bob Will | 1958 |

| John Buzhardt | 1959 |

| Seth Morehead | 1960 |

| Jack Warner | 1962 |

| Jim Brewer | 1962–63 |

| Dick Scott | 1964 |

| John Flavin | 1964 |

| Rick James | 1967 |

| Bobby Tiefenauer | 1968 |

| Darcy Fast | 1968 |

| Don Nottebart | 1969 |

| Roe Skidmore | 1970 |

| Ron Tompkins | 1971 |

| Jack Aker | 1972–73 |

| Geoff Zahn | 1975–76 |

| Willie Hernandez | 1977–83 |

| Tom Grant | 1983 |

| Ron Meridith | 1984–85 |

| Mike Capel | 1988 |

| Dean Wilkins | 1989–90 |

| Randy Kramer | 1990 |

| Billy Connors (coach) | 1991 |

| Jeff Robinson | 1992 |

| Jose Bautista | 1993–94 |

| Jaime Navarro | 1995–96 |

| Dave Swartzbaugh | 1997 |

| Mike Morgan | 1998 |

| Marty DeMerritt (coach) | 1999 |

| Rick Aguilera | 1999–2000 |

| Manny Aybar | 2001 |

| Carlos Zambrano | 2001–11 |

| James Rowson (coach) | 2012–13 |

| Jacob Turner | 2014 |

Well he went down to dinner in his Sunday best Excitable boy, they all said

And he rubbed the pot roast all over his chest Excitable boy, they all said

Well he’s just an excitable boy …

—Warren Zevon, “Excitable Boy”

Rubbing pot roast on his chest was about the only thing the very excitable Carlos Zambrano (2001–11) didn’t do on the pitcher’s mound.

Carlos Zambrano had a hop on his fastball with an equal chance to see great pitcher or great temper.

We’re exaggerating here, a little. Z’s exuberant nature, his histrionics on the mound, his clear passion for playing baseball, made #38 worth keeping around for 11 seasons, even as he broke bats over his leg after striking out, or stomped off the pitcher’s mound like a petulant little child when being removed. Excitable Z was like a tremendous snow-capped mountain you could not believe you had a grand view of, but that same beautiful mountain could turn into a volcano and bury everyone in its path in lava—or B.S.

Z first came to the majors on August 20, 2001, debuting just two months past his twentieth birthday to become the first player born in the 1980s to reach the major leagues. Struggling at first as a reliever, he didn’t pitch consistently until manager Don Baylor put him in the starting rotation, ironically, only a few days before Baylor was fired in July 2002. (That’s the only legacy of Baylor for which Cubs fans can thank him.) Z immediately took to starting. Though posting only a 4–8 record in sixteen starts in 2002, he had a 3.68 ERA and struck out ten Astros on July 20.

Zambrano went 13–11, 3.11 in 2003, and had a memorable confrontation with Barry Bonds at Wrigley Field on July 31 after fanning Bonds. Z went off the field pumping his fists and pounding his chest and threw the ball into the stands. Afterwards Zambrano was quoted as saying: “Well, I just try to be myself. I don’t try to embarrass anybody. He’s a big man in baseball. It was a situation that was a big deal in the game. I was happy.” Bonds’s response? “I don’t get upset about things like that, brother. He will learn respect eventually. I promise you. He’ll learn respect, I guarantee that.” (Guarantees aside, Bonds went 0 for 4 in his career against Zambrano, though Z walked him three times.)

Major league hitters learned to respect Z over the next several seasons, but not before he had a meltdown in Game 5 of the 2003 NLCS. He had to be yanked after five innings with the Cubs down 2–0, because he had walked four and thrown 113 pitches (a pattern that would repeat itself, disturbingly, far too often in the next few years). To be fair, no one was going to hit Josh Beckett that day—he threw a two-hit shutout—but Z had a chance to clinch the pennant for the Cubs and failed.

Zambrano won 125 games as a Cub with a 3.60 ERA and 1,637 strikeouts. And man, could he hit. A switch hitter with a .241 career average, he hit .300 in 2005, just the seventeenth pitcher to reach that plateau in the designated hitter era (since 1973). Three years later he batted .337—fifth highest to that point by a pitcher in the DH era. But Z sure didn’t believe in walks—at least at the plate (he twice led the league in walks issued). Z drew just 10 bases on balls in 744 career plate appearances. His 24 home runs, however, tied for seventh-most in major league history by a pitcher. His six longballs in 2006 tied the Cubs single-season mark set by Fergie Jenkins in 1971.

When his demeanor was more Big Z than El Toro, the 275-pound Venezuelan was worth his weight in gold. But it was only a matter of time until the Bull emerged. He was put on the restricted list following a midgame verbal tirade with teammate Derrek Lee in 2010. He finished the year 11–6 with a 3.33 ERA, though the anger management courses didn’t stick. The following year, after allowing five home runs against Atlanta—and somehow not getting pulled from the game—he threw two close pitches to Chipper Jones. El Toro was ejected and went into the clubhouse, cleaned out his locker, and announced his retirement. He later said he wanted to come back, but he never pitched again for the Cubs. He was sent to the Marlins for Chris Volstad and a ticket on the good ship Volatile with fellow countryman and hothead Ozzie Guillen. Neither Ozzie nor Z saw a second season with the Marlins.

Before Z’s time, #38 was the forgotten stepchild of Cubs numbers. Only one other player —Willie Hernandez (1977–83)—wore it for more than two seasons. Guillermo “Willie” Hernandez, a hard-throwing lefty, was infuriating: he’d be dominant for a while, then totally hittable. In his rookie year, 1977, he had a 3.03 ERA, but he also gave up 11 homers in 110 innings, all in relief save for one start Herman Franks gave him against the Cardinals on September 6. He threw well in that start, but Hernandez got no hitting support and the Cubs lost, 3–1. After several more up-and-down years, Dallas Green finally soured on Hernandez and sent him to the Phillies in another one of his “Philly Shuttle” deals, acquiring one of his personal favorites, Dick Ruthven. The Phillies should have hung on to him; instead, just before the 1984 season, they sent him to the Tigers, whom he helped win the world championship while claiming both the AL Cy Young and MVP awards. Come to think of it, the ’84 Cubs could have used him, too.

The rest of the #38’s can be separated into three different groups. There’s the short-timers in the World War II era: Dick Barrett (1943), Mickey Livingston (1943), Garth Mann (1944), Mack Stewart (1944–45), Johnny Moore (1945, a return wartime engagement at age forty-three, Moore had been one of the first Cubs to wear a number, donning #5 in 1932), and Ray Starr (1945). Then there’s the collection of guys who were better for other teams, either long before or long after they were Cubs: John Buzhardt (1959), Jim Brewer (1962–63), Bobby Tiefenauer (1968), Don Nottebart (1969), Jack Aker (1972–73), Geoff Zahn (1975–76), Jeff Robinson (1992), and Jaime Navarro (1995–96), who actually had two good years for the Cubs but had seen his better days for the Brewers. And there were prospects and suspects who never made it: Bob Zick (1954), Seth Morehead (1960), Jack Warner (1962), Dick Scott and John Flavin (both in 1964 and both with an ERA north of ten), Rick James (1967), Ron Tompkins (1971), Tom Grant (1983), Ron Meridith (1984–85), Mike Capel (1988), whose main claim to fame was that he was a college teammate of Roger Clemens’s at Texas, Dean “No Relation To Rick” Wilkins (1989–90), Randy “Not The Seinfeld Character” Kramer (1990), Dave Swartzbaugh (1997), and Manny Aybar (2001).

There are three other stories worth telling among the #38 slugs. Roe Skidmore (1970), a native of downstate Decatur, is one of the few major leaguers to retire with a perfect 1.000 batting average. Acquired from the Giants in the 1968 minor league draft, Skidmore was sent up to pinch-hit for pitcher Joe Decker in the seventh inning on September 17, 1970, with the Cubs trailing, 8–1. He singled, and was forced at second to end the inning. Despite being sent to the White Sox, Reds, Cardinals, Astros and Red Sox in various deals over the next four years, that was his only major league plate appearance.

Jose Bautista (1993–94) was born in the Dominican Republic and had four so-so years for the Orioles before the Cubs signed him as a free agent at the end of the 1992 season. He had one good year (’93) and one not-quite-so-good (’94), but his background is the most interesting part of his story. He is the son of a Dominican father and an Israeli mother, and he and his family are apparently quite observant Jews. When asked about his faith, Bautista told the Village Voice: “My family and I go to synagogue when we can and we pray every Friday. We fast on Yom Kippur and not only do I not pitch, I don’t even go to the ballgame.”

Finally, Darcy Fast (1968) had a name that seemed destined for fame; it’s a great baseball name, especially for a pitcher, although his full name (Darcy Rae Fast) seemed as if his parents expected a girl rather than a boy. Fast, a left-hander, was selected in the sixth round of the 1967 draft and a year later was in the major leagues; he pitched in eight games, starting one, and posted a 5.40 ERA at age twenty-one. Hopes were high for him to be in the 1969 rotation or bullpen—except for one thing. Uncle Sam called him up first. He was drafted into the Army, and though the Cubs tried to get him an exemption by sending him back to college and getting a student deferment or getting him into the National Guard, there was some sensitivity to that sort of thing—athletes getting preferential treatment—and so he spent 1969 in a military uniform rather than a Cubs uniform. He tried to come back in 1970 but hurt his arm and was traded to the Padres. When he submitted his voluntary retirement papers from baseball at age twenty-four, commissioner Bowie Kuhn sent him a letter telling him he was one of the youngest, if not the youngest, to ever do so. Eventually he went into the ministry; Cubs fans are left to wonder what might have been had Darcy Rae Fast been in Leo Durocher’s bullpen on September 7, 1969, when Willie Stargell stepped to the plate in Wrigley Field with two out and a victory on the line.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #38: Garth Mann (1944). Though a pitcher by trade, Mann’s only major league appearance came as a pinch runner in the second game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field on May 14, 1944. The Cubs had lost the first game to the Dodgers 4–2 to drop to a 2–16 record, already twelve games out of first place only eighteen games into the season. Mann ran for Lou Novikoff, who had led off the eighth inning with a single. After Bill Nicholson doubled him to third, Mann scored on an Andy Pafko single. The Cubs won the game, 8–7. Six days later, Mann was sent back to the minors. He was recalled later in the season and issued #45, but never again appeared in a major league game.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #38: Rick Aguilera (1999–2000). When Rod Beck went down with an injury in early 1999, the Cubs, then considering themselves contenders (and they were, peaking at 32–23, only a game out of first place on June 8th), felt they needed an “established” closer. So they sent two minor leaguers to the Twins for Aguilera, who had posted 281 saves for the Twins, Red Sox, and Mets and who had played for two World Series winners. Aguilera was awful. He blew a save to the Marlins in spectacular fashion in his second Cubs appearance, capped by a three-run homer hit by Kevin Millar, and “Aggie” (could that nickname be short for “Aggravating”?) was routinely booed after that. Though he posted 37 saves in a Cubs uniform—including the 300th of his career—he also had 13 blown saves and a 4.31 ERA. The guy the Twins were after in the deal was Jason Ryan, at the time the Cubs’ top pitching prospect. But they asked for another pitcher as a “throw-in”— and that was Kyle Lohse. Ryan pitched in only sixteen major league games with a 1–5, 5.94 mark, but Lohse became a solid rotation starter for fifteen seasons.

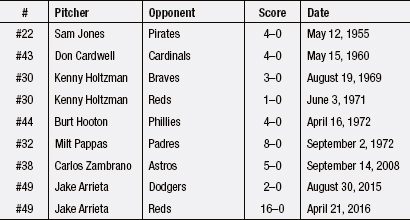

No-No Numbers

Nine Cubs no-hitters have come since the numbers first went on the uniforms in 1932, Kenny Holtzman tossed two wearing #30—Jake Arrieta (#49) matched the dual no-no feat—but Holtzman’s second (in Cincinnati) is the only one thrown by a Cub on turf and the 1–0 score makes it the tightest score in a Cubs no-hitter. At the other end of the spectrum, Arrieta’s second was the highest margin of victory, 16–0, in Cubs history, and the highest in any no-no since 1884. Zambrano’s 2008 no-hitter was the first indoor Cubs no-no and the first ever tossed at a neutral site. The game took place at Milwaukee’s Miller Park after the Astros were forced to host two games there because of Hurricane Ike.