#39: ABBY, KRUKE, AND SOUP

| ALL-TIME #39 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Stan Hack | 1935–36 |

| Bob Logan | 1937 |

| Bob Garbark | 1937–39 |

| Bob Collins | 1940 |

| Ray Prim | 1943, 1945–46 |

| Hank Miklos | 1944 |

| Red Lynn | 1944 |

| Roy Smalley | 1948–53 |

| Dave Cole | 1954 |

| Steve Bilko | 1954 |

| Monte Irvin | 1956 |

| Chuck Tanner | 1957 |

| Ed Mickelson | 1957 |

| Jack Littrell | 1957 |

| Moe Drabowsky | 1959–60 |

| Tony Balsamo | 1962 |

| Paul Toth | 1962–64 |

| Paul Jaeckel | 1964 |

| Bob Humphreys | 1965 |

| Ted Abernathy | 1965–66 |

| Curt Simmons | 1966–67 |

| Archie Reynolds | 1968, 1970 |

| Dick Selma | 1969 |

| Hoyt Wilhelm | 1970 |

| Ellie Hendricks | 1972 |

| Jim Todd | 1974 |

| Eddie Watt | 1975 |

| Ken Crosby | 1975–76 |

| Mike Krukow | 1977–81 |

| Bill Campbell | 1982–83 |

| George Frazier | 1984–86 |

| Ron Davis | 1986–87 |

| Paul Kilgus | 1989 |

| Jose Nunez | 1990 |

| Laddie Renfroe | 1991 |

| Scott May | 1991 |

| Eddie Zambrano | 1993 |

| Mike Walker | 1995 |

| Robin Jennings | 1996 |

| Tom Gamboa (coach) | 1998–99 |

| Willie Greene | 2000 |

| Steve Smyth | 2002 |

| Dick Pole (coach) | 2004–06 |

| Matt Sinatro (coach) | 2007–10 |

| Lou Montanez | 2011 |

| Dave McKay (coach) | 2012–13 |

| Jason Hammel | 2014–15 |

Ted Abernathy’s signature submarine pitching motion has been implemented over the years by several successful relief pitchers, notably Dan Quisenberry, and today Darren O’Day, whose knuckles occasionally scrape the ground. For Abernathy, the underhanded motion was adopted out of necessity, not choice. He had shoulder surgery and after a few attempts to make the Washington Senators in the late 1950s, he spent two years in the minors reinventing himself as a reliever.

For one spectacular season—1965, after the Cubs purchased his contract from the Indians—Abernathy was virtually unhittable. Posting a 2.57 ERA, he threw what today would be an unheard-of 136.1 innings in relief. His record total of 31 saves is modest by the standards of today, where his long-surpassed mark was doubled by Francisco Rodriguez of the Angels in 2008. Abernathy was a pioneer—he wasn’t used as modern closers are, pitching only in the ninth inning with a lead—but he was among the first pitchers to be used exclusively to close out or “save” games. Of Abernathy’s then-record 84 appearances, 48 logged more than three outs; the year K-Rod set the saves record in 2008, he had no appearances of more than three outs. Abernathy was only the second pitcher since 1900 to pitch in more than the nineteenth century record of 76—back when 76 games meant 76 games started (or technically, 75 starts and one relief appearance, by Will White in 1879 and matched by Pud Galvin in 1883—but you get the idea). Abernathy’s 84 games broke Bill Hutchinson’s franchise record of 75 appearances (70 starts) set in 1892; Abernathy’s mark is still the team record (it’s been tied twice, by Dick Tidrow in 1980 and Bob Howry in 2006). It was a spectacular year by Abernathy—for a 90-loss Cubs team.

But when Abby got off to a bad start in 1966, the Cubs figured he was done at age thirty-three, and dumped him to the Braves, who in turn shipped him to Cincinnati—where he had two fine years in 1967 and 1968. That prompted the Cubs to reacquire him for what we’d now consider a setup role to Phil Regan, this go-around wearing #37.

Part of the Rick Sutcliffe trade booty, George Frazier gave the mid-1980s Cubs innings out of the bullpen, if little else.

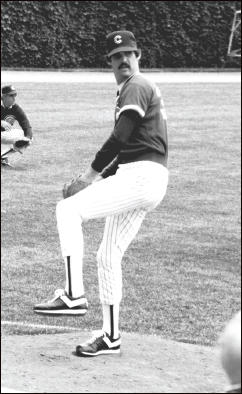

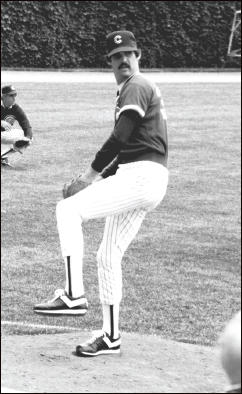

Most of the other players to wear #39—virtually all pitchers—were short-timers with the club. One notable exception was Mike Krukow, who came up through the Cubs farm system and first made the rotation at age twenty-five in 1977. Solid but unspectacular, he was basically a .500 pitcher for the North Siders and was sent to the Phillies by Dallas Green before the 1982 season in one of several deals with his old club. Later traded to the Giants, he has made his home in the Bay Area and become one of the better broadcasters in the game, for Giants TV.

The Krukow deal made room for #39 to be worn by Bill “Soup” Campbell, he of one of the more contrived nicknames in recent baseball history (really—they couldn’t do better than “Campbell Soup”?). Several years removed from some big winning and saving years for the Twins and Red Sox (17 wins, 20 saves in 1976; 13 wins, 31 saves in 1977), Campbell was supposed to be the Cubs’ closer…but Green hadn’t counted on Lee Smith grabbing that job by the horns. Relegated to a setup role, Campbell’s sour countenance mirrored his play. A 4.49 ERA in 1983 got him traded to—where else?—Philadelphia, as part of the deal that brought Gary Matthews and Bob Dernier to the Cubs, two key parts of the ’84 NL East champions.

Probably the 1984 deal most responsible for the division title involved Rick Sutcliffe coming from Cleveland in June, but the deal also brought catcher Ron Hassey and reliever George Frazier (1984–86). Frazier had a 15–15 mark out of the Cubs pen despite a cringe-inducing 5.36 ERA in 123 games as a Cub. Not surprisingly, he was hit hard in his lone postseason appearance, in Game 3 of the ’84 NLCS. But it was an improvement over his last postseason, with the ’81 Yankees. That October he’d become the first pitcher to ever lose three games in one World Series.

Another pitcher, Ray Prim, would be a forgotten footnote in Cubs history had he not had one of those seasons that historians would say was made possible by a “war-weakened” league. Prim went 13–8, 2.40 for the 1945 NL champions, leading the NL in ERA. He was thirty-eight years old and hadn’t pitched in the majors in eight years before the war, and didn’t pitch in the ’45 World Series. His ERA ballooned to 5.79 in ’46 and he retired.

The only significant non-pitcher to wear #39 was Roy Smalley, whose son, Roy Jr., had a 13-year career mostly in the AL, hitting 163 homers. Roy Sr. had power, too. His 21 homers in 1950 helped the Cubs to total of 161, good for second in the league. Roy Sr. also made 51 errors in ’50, which led the league, and made Cubs fans with a wicked sense of humor say that the seventh-place club’s double play combination was “Miksis to Smalley to Addison Street.”

The usual lists of prospects/suspects include Chuck Tanner (1957), later a World Series-winning manager; Paul “Four Games Of The” Jaeckel (1964); Archie Reynolds (1968, 1970), the only Cub ever named “Archie”; Jose Nunez (1990), who had a 2.57 ERA in 11 relief appearances but a 7.71 ERA when then placed in the rotation; Laddie Renfroe (1991), the only Cub ever named “Laddie”; Scott May (1991), not the former NBA player—and not much of a pitcher, either, with an 18.00 ERA in two games; Eddie Zambrano (1993), the Cubs’ second-best Zambrano; and Robin Jennings (1996), the only major leaguer born in Singapore. Three players playing out the string were Monte Irvin (1956), Curt Simmons (1966–67), and Ellie Hendricks (1972), each of whom prompt the question, “He played for the Cubs?” Yes, they did: Irvin and Simmons spent their final major league seasons at Wrigley while Hendricks played seventeen games with a .116 average in 1972 before making a U-turn and being traded back to Baltimore, from whence he came, two months after he arrived. Willie Greene (2000) never played in the majors again after hitting .201 in 299 at-bats for that 97-loss team.

Pitcher Dick Selma (1969) deserves special mention because, despite spending less than one season on the North Side, he will be remembered in Wrigley Field lore forever for his antics with the Bleacher Bums. The Bums, in those days a quasi-organized yellow-helmeted group in left field, befriended Selma, who used to lead them in cheers. From his acquisition in late April 1969 through August 17, Selma went 10–2 with a 2.96 ERA and it looked like the twenty-five-year-old would be a Cub for years to come. But Selma got himself into Leo Durocher’s doghouse permanently when he made an attempted pickoff throw toward Ron Santo on September 11, 1969 in Philadelphia—only Santo wasn’t covering the base. The Phillies tied the game and eventually won it, giving the Cubs their eighth loss in a row. Selma was sent, ironically, to the Phillies along with Oscar Gamble for Johnny Callison before the 1970 season in one of the Cubs’ worst deals of the time.

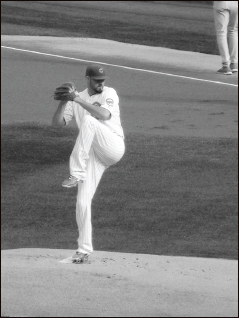

Jason Hammel (2014–15) is the best #39 since at least Mike Krukow, and perhaps all the way back to the aforementioned Ted Abernathy. Hammel was second banana in the Jeff Samardzija deal, except he came back as a free agent, while the guy with the hard-to-spell name ended up on the South Side or South Bend or wherever. In his first season and a half since coming from Baltimore at age 31, Hammel went 18–12 with a 3.45 ERA in 48 starts. And this book has to give a thumbs up to anyone who has an M.C. Hammer pun and a uniform number in his Twitter handle: @HammelTime39. Can’t touch this.

Jason Hammel provided a big leg up after coming to Chicago.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #39: Tony Balsamo (1962). Sounding more like a character from The Sopranos, Balsamo was one of the revolving-door pitchers who pitched for the revolving College of Coaches in the horrid 1962 season. Balsamo, who played college ball at Fordham, never pitched in a winning major league game. Pitching entirely in April, May, and June, he was the very definition of mop-up man, earning only one decision (a loss in a 13-inning game to the horrid Mets on May 15). The Cubs were outscored 165–77 in his eighteen appearances.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #39: Hoyt Wilhelm (1970). You can win trivia contests with this one. Hall of Famer Wilhelm, who is the only player to hit a homer in his first major league at-bat and never hit another one, pitched in three games for the 1970 Cubs, who picked him up off waivers with ten games left in the season. Several years removed from his successful years as a White Sox reliever, the forty-seven-year-old Wilhelm threw mop-up duty in three losses and then was sent to Atlanta; he had two more major league years left with the Braves and Dodgers.

How ’Bout Them Colts?

One thing you need to know about the Cubs is that they are old. That’s not a dig on the advancing age of David Ross. We’re talking about the franchise.

The Cubs date to the dawn of the first professional league, the National Association, in 1871. They are so old that the Great Chicago Fire kept them off the field for two years. They returned in 1874, led the coup that resulted in the formation of the National League in 1876, and along with the Braves are the oldest existing franchises in baseball. In the early years, the Braves—then in Boston—were referred to as the Red Stockings and the Cubs were the White Stockings. By 1901 the Cubs had abandoned “White Stockings,” and so the upstart American League franchise granted to Chicago that year took it as its own, to trade off the popularity of the Chicago National League Ball Club; the name had a decent enough ring to still be in use today (albeit shortened to “Sox”) in that nouveau 115-year-old AL.

Sports nicknames weren’t as much a part of the culture in the 19th century as they are in the 21st. The team was often called the Chicagos on the road and by a range of names when at home, including Remnants, Babes, Rainmakers, Recruits, Orphans, Cowboys, and Broncos. Colts was perhaps the most popular and Orphans the most memorable; they were called the latter after legendary first baseman and manager Cap Anson was discharged following the 1897 season.

The team’s home shifted almost as often as its nickname: Union Street Grounds (1871), 23rd Street Grounds (1874–77), two versions of Lakefront Park (1878–84), West Side Park (1885–1891), South Side Park—gasp! (1891–1893), and West Side Grounds, where the franchise had its greatest years from 1893 until they moved into Weeghman Park in 1916. The park changed monikers to Wrigley Field a decade later, but the Cubs name stayed.

Keep in mind that all these names came to pass before a Cub ever donned a uniform number. The number they were predominantly known as were the Chicago nine. And Chicagoans, whether in suits and bowler caps or floppy hats without any shirt, have always loved ’em.