#41: WEATHERS, RAIN, AND DIRT

| ALL-TIME #41 ROSTER | |

| Player | Years |

| Red Corriden (coach) | 1932 |

| Carroll Yerkes | 1932–33 |

| Dolph Camilli | 1933–34 |

| Don Hurst | 1934 |

| Ken O’Dea | 1935–36 |

| John Bottarini | 1937 |

| Bob Logan | 1938 |

| Vance Page | 1938–41 |

| Vallie Eaves | 1941 |

| Dick Spalding (coach) | 1943 |

| Milt Stock (coach) | 1944–48 |

| Carmen Mauro | 1948–51 |

| Bud Hardin | 1952 |

| Ray Blades (coach) | 1954–56 |

| Seth Morehead | 1958–59 |

| Taylor Phillips | 1959 |

| Art Ceccarelli | 1959–60 |

| Billy Williams | 1960 |

| Barney Schultz | 1961–63 |

| Tom Baker | 1963 |

| Sterling Slaughter | 1964 |

| Roberto Pena | 1965 |

| Adolfo Phillips | 1966 |

| Fred Norman | 1966–67 |

| Rob Gardner | 1967 |

| Lou Johnson | 1968 |

| Dave Roberts | 1977–78 |

| Dick Tidrow | 1979–82 |

| Warren Brusstar | 1983–85 |

| Mike Martin | 1986 |

| Mike Mason | 1987 |

| Jeff Pico | 1988–90 |

| Jim Essian (manager) | 1991 |

| Tom Trebelhorn (coach) | 1992–93 |

| (manager) | 1994 |

| Bryan Hickerson | 1995 |

| Roberto Rivera | 1995 |

| Marc Pisciotta | 1997–98 |

| Steve Rain | 1999–2000 |

| David Weathers | 2001 |

| Jesus Sanchez | 2002 |

| Larry Rothschild (coach) | 2003–06 |

| Lou Piniella (manager) | 2007–10 |

| Tony Campana | 2011 |

| Justin Germano | 2012 |

| Jose Veras | 2014 |

| Matt Szczur | 2014–15 |

Perhaps the most famous wearer of uniform #41 in Cubs history is manager Lou Piniella. He wore #14 as a player but, for the second time in his managing career, Lou had to reverse this number because he managed a team for which #14 was retired (Reds: Pete Rose; Cubs: Ernie Banks). In the final four seasons of a twenty-three-year managing career (on top of an eighteen-year playing career), Piniella had a .519 winning percentage and two division titles with the Cubs. Lou was the third Cubs skipper to don #41. He certainly cut a far more colorful and successful path than Jim Essian or Tom Trebelhorn.

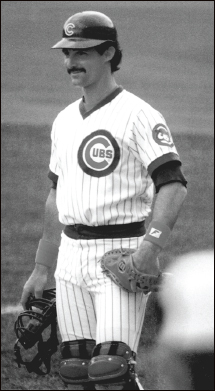

But we’re here to get down and dirty with three pitchers who wore #41: Dick “Dirt” Tidrow, Steve Rain, and David Weathers. And the order in which they appeared in Cubs uniforms seems appropriate, too. First, “The Dirt Man,” Dick Tidrow, a sidewinding right-hander with a classic ’70s walrus stache and a uniform that he managed to get filthy before he even got into the game. In the typical style of the later years of the Wrigley ownership of the team, Tidrow was acquired after he had success elsewhere (two World Series rings with the Yankees in 1977 and 1978), hoping he could replicate that success on the North Side.

While Tidrow did have several decent seasons as a middle reliever—including going 11–5, 2.72 in 63 games for the 1979 Cubs after his acquisition for Ray Burris on May 23—the Cubs never had a winning record in his nearly four seasons. Dirt was durable. Counting his outings with the Yankees, he pitched 77 times in ’79 and led the Cubs in appearances for three consecutive years. Dirt’s 84 appearances for the woeful 1980 Cubs tied Ted Abernathy’s 1965 record. That mark still stands, having been tied again by Bob Howry for yet another horrid Cubs team in 2006.

The Dirt was washed away, so to speak, by the “Rain Man.” Steve Rain was considered a top Cubs relief prospect in the late 1990s. Despite a decent performance for yet another execrable Cubs team in 2000 (54 strikeouts in 49.2 innings over 37 appearances), Rain became a free agent and never again pitched in the major leagues.

The number was next worn by David Weathers, maintaining our meteorological bent, but not without some confusion. He was initially issued #49 in his first games after his acquisition by the Cubs on July 30, 2001, games all played on the road. When the Cubs returned home to Chicago he was going to switch to #48—and the printed Wrigley Field scorecards had him listed that way—but Joe Borowski, who appeared in only one 2001 Cubs game, was still on the 40-man roster and had claim to #48, so Weathers took #41 instead. The 2001 Cubs, contenders up to that time, hoped he would help them make the postseason. They didn’t weather the rest of the season, though, finishing third. Weathers left the Cubs as a free agent after appearing in only 28 games.

Number 41, famously retired by the New York Mets for Tom Seaver, has a more checkered history for the Cubs. Before World War II, #41 was worn by the forgettable Don Hurst (1934), Ken O’Dea (1935–36), John Bottarini (1937), and Bob Logan (1938). In the prewar era, only Dolph Camilli (1933–34), who was traded to the Phillies on June 11, 1934 for Hurst in perhaps the worst trade the Cubs made in the ’30s (Camilli went on to have eight straight twenty-plus homer seasons for the Phillies and Dodgers, while Hurst hit .199 in 51 games and left the majors after ‘34), is a recognizable name on the #41 roster. Vance Page (1938–41) did start nine games, winning five, for the 1938 NL champions, but when called on to keep a 4–3 game close in Game 4 of the ’38 World Series, he gave up two runs and the Yankees wound up winning that clinching game, 8–3. The equally forgettable Carmen Mauro (1948–51), Seth Morehead (1958–59), and Taylor Phillips (1959) wore it through most of the rest of the ’40s and ’50s. Art Ceccarelli (1959–60) went 5–5, 4.85 in 28 games before he was sent to the Yankees on May 19, 1960, leaving #41 for Hall of Famer Billy Williams to wear during his second September callup (he wore #4 in 1959). Williams was assigned his now-retired #26 for his Rookie of the Year campaign in 1961.

From the 1960s on #41 has been almost exclusively reserved for pitchers, and mostly forgettable ones (Tom Baker, Sterling Slaughter, Rob Gardner, Mike Mason, Roberto Rivera, Bryan Hickerson, and Jesus Sanchez are perhaps the least memorable of the forgettable; none of them were Cubs for more than a season). Jeff Pico (1988–90) threatened to rescue #41 from obscurity when he shut out the Reds on four hits in his major league debut on May 31, 1988, but Pico’s three-year Cub (and major league) career ended with a 13–12 record and 4.24 ERA, and he wore #41 for all but one game—that first one; he threw that four-hit shutout in #51 (maybe he should have kept that number). And #41 was worn briefly by Adolfo Phillips before he switched to #20, and by catcher Mike Martin (1-for-13 in 1986),the last position player to wear #41 until Tony Campana (2011–12), a spare outfielder with little power to spare.

Mike Martin smiles as if he knew that three decades after he hit .077 in his only season in the majors, he’d have his picture in a Cubs book.

Justin Germano is noteworthy only because he made 12 starts (and one relief outing) and had 12 decisions for the 2012 Cubs. It was not pretty: 2–10 with a 6.75 ERA. He pitched just three more games with two more teams. And he did not pitch well. Matt Szczur (2014–15) has more consonants in his name than he’s had chances breaking into a mostly stacked Cubs outfield, but he’s still young. His predecessor at #41, well traveled reliever Jose Veras, seemed done at age thirty-four when the Cubs released him with an 8.10 ERA in June 2014. He signed with the Astros and finished the season 4–0 with an ERA just north of 3.00. Roberto Pena, known as “Baby,” played in parts of two seasons. Baby, did he get his hands on some numbers in that time. Pena was a non-roster playing during the spring of 1965; in camp, he wore #1, which wasn’t worn by a player during the regular season between 1961 (Richie Ashburn) and 1972 (Jose Cardenal). Ron Campbell, who had worn #7 in 1964, was sent to the minors at the end of spring training and Pena made the club, taking over Campbell’s #7. On May 29, the Cubs acquired Harvey Kuenn from the Giants, and Kuenn was given #7, the number he’d worn in San Francisco. Pena switched to #41—but only for a couple of weeks, as on June 10, he was sent to the minors. In September, he was recalled and given #28, which he wore through the rest of 1965 (though he played in only one September game) and six games in April 1966. By Yosh’s System, as described in Chapter 40, Pena, an infielder, should have worn a number in the teens, but they were all taken (save #16, which was still being set aside in memory of Ken Hubbs). Pena, Wimpy Quinn (#4, #16, #19: 1941) and Ryan Theriot (#55, #7, #3: 2006) are the only Cubs to wear three different numbers in a single season. What did all this numerical maneuvering do for Pena? It’s hard to say, but the numbers that linger for the rookie shortstop: .218, two homers, 12 RBI, 17 errors in 51 games weren’t good. He played for four other teams and was better at the plate and in the field, though only once did he wear the same uniform number in successive seasons.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #41: Bud Hardin (1952) wore #41 and played in three games between April 15 and May 1, having seven at-bats and one hit, a single. We put him in this book because otherwise no one outside his family would remember him. And if you do remember William Edgar Hardin: This Bud’s for you.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #41: Lou Johnson (1968) actually came up as a Cub in 1960, was sent packing after hitting .206 in 68 at-bats, had several good seasons as a Dodgers outfielder (hitting .296 in the 1965 World Series), and was reacquired for Paul Popovich and Jim Williams in the 1967–68 offseason. After hitting .244 in half a season, he was sent to Cleveland for Willie Smith in one of the better transactions of the John Holland era.

Making Music in ’41

Of all the singers of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” over the years, Harry Caray is the best remembered today. He started singing the song over the PA at Comiskey Park when White Sox owner Bill Veeck tricked him into doing it in the 1970s, but it was serendipity that in 1982 teamed him with the place that had the first organ in the big leagues: Wrigley Field. By then, Veeck was sitting in the bleachers on the North Side as well. Veeck had helped plant the Wrigley ivy in 1937 while working for his dad, club president Bill Veeck Sr. Bill Veeck the Younger had also been around when the Cubs brought organ music to the big leagues.

No stadium had a ballpark organ until Wrigley Field installed one on April 26, 1941. According to Craig Wright at BaseballPast.com, the Cubs hooked up the organ to the public address system as a one-time gimmick. The fans loved it and it became permanent. It would be almost another half-century before Wrigley would light up the nights, but the organ would brighten the days at the Friendly Confines for generations.