#44: FROM CAVVY TO RIZZO

| ALL-TIME #44 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Phil Cavarretta (player) | 1941–50 |

| (player-manager) | 1951–53 |

| Burt Hooton | 1971–75 |

| Mike Garman | 1976 |

| Dave Giusti | 1977 |

| Ken Reitz | 1981 |

| Dick Ruthven | 1983–86 |

| Drew Hall | 1986–88 |

| Steve Wilson | 1989–91 |

| Jeff Hartsock | 1992 |

| Bill Brennan | 1993 |

| Amaury Telemaco | 1996–98 |

| Chris Haney | 1998 |

| Tony Fossas | 1998 |

| Kyle Farnsworth | 1999–2004 |

| Roberto Novoa | 2005–06 |

| Chad Fox | 2008 |

| Chad Fox | 2008–09 |

| Jeff Stevens | 2010–11 |

| Anthony Rizzo | 2012–15 |

Phil Cavarretta was a leader on the Cubs’ pennant-winning teams of the 1930s and 1940s, and one of the greatest all-time Cubs, still ranking tenth on the team’s all-time lists for runs, hits, RBI, and plate appearances while placing seventh all-time in walks, sixth in games played, and fifth in triples (through 2015). He was NL MVP in 1945, managed the club for 2½ seasons, and helped the Cubs to three pennants while twice batting .400 in the World Series. He got some Hall of Fame consideration, receiving a number of votes in the 1960s and 1970s including thirty-five percent of the necessary vote in 1975. To compare him to a modern-day Cub, his numbers—good average, little power—were similar to Mark Grace’s. Numbers-wise, he was the first Cub to wear 43 and 44. He did everything the club ever asked of him, except lie.

The Lane Tech High School star hit for the cycle in his first professional game in Peoria. Soon after, Cavarretta was promoted to the majors at age eighteen, and he was Chicago’s first baseman as a teenager in the 1935 World Series loss to the Tigers. The Cubs won the pennant again three years later, with Cavarretta moving to right field to make room for Ripper Collins. An ear problem exempted him from military service during World War II and he provided stability to a lineup in constant flux. In 1945 he won the NL batting title and MVP while helping the Cubs reach the World Series for the third time in a decade. He made the All-Star team four straight times and then took a seat on the Cubs bench to let younger players get a chance. Even as a reserve he was still a crack hitter and a preacher of patience—toss out his last four at-bat season with the White Sox, and he had more walks than strikeouts in fifteen of his final sixteen seasons.

The Cubs fired Frankie Frisch midway through the 1951 season and made Cavarretta player-manager. In 1952 the team finished at .500—no small feat for those Cubs, and the only time between 1946 and 1963 that they didn’t have a losing record—and the ’53 club, although seventh at 65–89, still did better than expected given the team’s scoring (for and against). The following spring, Cavarretta was asked by owner P.K. Wrigley how he felt the team would do, and, being honest, said, “They’re a second-division club.” (In 1950s baseball speak, that meant he thought the team wouldn’t be any good.) Wrigley promptly fired the Chicago legend, saying he had a “defeatist attitude,” making Cavvy the first post-1900 manager to be dismissed during spring training. Cavarretta was asked about this for a July 2008 article that appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, and said:

Like a dumb dago, I told the truth in a meeting with my owner. I was raised that way. My dad would always say: ‘Tell the people the truth. Tell them what’s on your mind.’ I told the truth to Mr. Wrigley and got fired.

Cavvy was telling the people the truth—the 1954 Cubs lost 90 games and finished seventh under Cavarretta’s former teammate, Stan Hack.

Finally, according to a Chicago Tribune article published April 2, 1954, the Cubs “officially” retired Cavarretta’s #44 the previous day. No ceremony was held for the just-fired manager, and on May 24, 1954 Cavvy signed with the rival crosstown White Sox, finishing his career at Comiskey Park as a bench player. The number wasn’t reissued until 1971, when University of Texas star Burt Hooton, who had worn the number in college, asked to wear it (it had been worn in spring training, but not in the regular season, between 1954 and 1970). Cubs clubhouse manager Yosh Kawano, who issued numbers for players from the 40s through the 80s, actually called Cavarretta to ask his permission to reissue the number.

Fifteen other Cubs have worn Cavarretta’s #44, which probably should have stayed retired in honor of one of the franchise’s greatest players. In fact, #44 is a retired number for many greats in baseball and other sports, from Henry Aaron to Willie McCovey to Reggie Jackson to the NFL’s Floyd Little and the NBA’s Jerry West. But for the Cubs, it’s been donned mostly by a succession of journeymen, all but one (Ken Reitz, 1981) a pitcher. Until 2012.

The Cubs may yet have their #44 slugger for the twenty-first century with first baseman Anthony Rizzo. He arrived in Chicago in 2012 and initially struggled—like his team. But in both 2014 and ’15 he hit 30 home runs, finished in the top ten in MVP balloting, and made the All-Star team. Popular, Italian, and honest—that sound like someone familiar? Phil Cavarretta would certainly have approved of Rizzo taking his number, but alas, Cavvy died in 2010, two years before Rizzo donned the uniform after coming over in a trade for Andrew Cashner in a deal the Padres wish they could have back.

Speaking of trades a team would love to do over, three years after he received #44 from the accommodating Cavarretta, the Cubs shipped Happy Hooton (called that for his perpetually glum countenance) to the Dodgers for Eddie Solomon and Geoff Zahn. (Solomon pitched six times as a Cub, while Zahn won 105 games after the Cubs released him.) And this was after Hooton started his Cubs career as if he, not Cavarretta, would be the one they’d be retiring #44 for someday. And it would stay retired. Following a brief appearance right after he was taken with the second overall pick in the June 1971 draft, Hooton spent the rest of the year in the minors until a late-season callup. In his first major league start on September 15, he tied the Cubs’ then-club record of 15 strikeouts against the Mets. Six days later, facing those same Mets, he threw a two-hit shutout. Then after a few months off, he threw a no-hitter against the Phillies at Wrigley in the second game of the 1972 season.

Dick Ruthven’s best years were long gone, but that didn’t stop the Cubs from trading future Cy Young and MVP winner Willie Hernandez for him in 1983.

For the most part, though, Hooton received little run support from his teammates and poor instruction from coaches who tried to get him to throw pitches other than his pioneering knuckle-curve. After going 34–44 in three-plus years and starting out poorly in 1975, he was traded to the Dodgers. Hooton stayed in LA for nearly a decade and was a key contributor to three Dodger pennant winners.

After Hooton was dealt, #44, once worn with such pride by Cavarretta, it was part of a parade of journeyman pitchers such as Mike Garman (1976), whose main claim to fame is that he pitched one year for the Cubs and then helped bring Bill Buckner to the North Side when traded to the Dodgers; Dick Ruthven (1983–86), one of the Phillies Connection guys brought over by Dallas Green when he took over as GM after Tribune Co. bought the team; Drew Hall (1986–88), yet another in a long line of failed Cubs top choices; Bill Brennan (1993), whose stork-like pitching delivery didn’t help him post better numbers; and Amaury Telemaco (1994), whose name sounds like a South American telephone company. In recent years, #44 has been sported by Chris Haney (1998), Tony Fossas (1998), Roberto Novoa (2005–06), Chad Fox (2008), and Jeff Stevens (2010–11). All of the aforementioned pitchers should be happy we mention nothing more than their names in this chapter.

And that leaves the best—well, weirdest, anyway—story for last. Kyle Farnsworth (1999–2004), heartthrob of female Cubs fans was known (sort of) affectionately as “Dr. Tightpants” for, well, the way he wore his uniform trousers. Farnsworth was a forty-seventh-round draft pick in 1994 who came up through the system throwing a fastball at speeds up to 100 MPH, although not always knowing where it would end up. He arrived in the bigs as a twenty-three-year-old starter in 1999. On August 29, he threw the only complete game of his career, a two-hit shutout at Dodger Stadium. The Cubs needed heat in the pen and felt that the Georgia native was durable enough to take the daily usage. Starting in 2001, he had a strong alternating-year pattern—good one year, bad the next. One of the NL’s top setup men in 2001, Farnsworth broke his foot the following April. The official story was that it was while warming up in the bullpen, but rumor had it that Farnsworth had been fooling around before a game kicking footballs in the outfield. He missed two months, and was ineffective thereafter. After a good season in 2003 his fastball started to lose its punch and with his velocity down and work ethic in question, he was dealt to the Tigers after the 2004 season for Scott Moore, Bo Flowers, and Roberto Novoa, who took over Kyle’s #44.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #44: Jeff Hartsock (1992), who had been highly touted when acquired in 1991 from the Dodgers for fellow #44er Steve Wilson (1989–91), went 5–12, 4.37 for the Cubs’ Triple-A team at Iowa in ’92, and for some reason got a September recall anyway. Hartsock pitched in relief four times, was bad in all of them (posting a 6.75 ERA in 9.1 innings) and the Cubs lost each game he appeared in, by a combined score of 46–13.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #44: We could have given this to Ken Reitz, acquired along with Leon Durham in the Bruce Sutter trade after the 1980 season. The slick-fielding Reitz couldn’t hit a lick (.215 in 82 games) and was released just before the 1982 season. But the guy who really didn’t seem as if he belonged in a Cubs uniform was palmballist Dave Giusti (1977), a former closer for the Pirates who seemed to take delight in tormenting the Cubs during Pittsburgh’s heyday in the early 1970s. Also pitching for Houston and St. Louis, Giusti had put up a 23–9, 2.98, 15-save record against the Cubs, his best record against any team he faced for more than 100 career innings. As was typical of the Cubs in that era, they went out of their way to acquire a washed-up guy (age thirty-seven) who had dominated them years earlier (fortunately, they only gave money, not prospects, to get him). Giusti was justifiably awful, recording a 6.04 ERA in 20 games before being released at the end of the season.

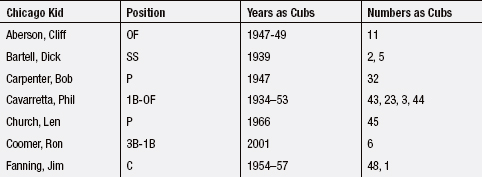

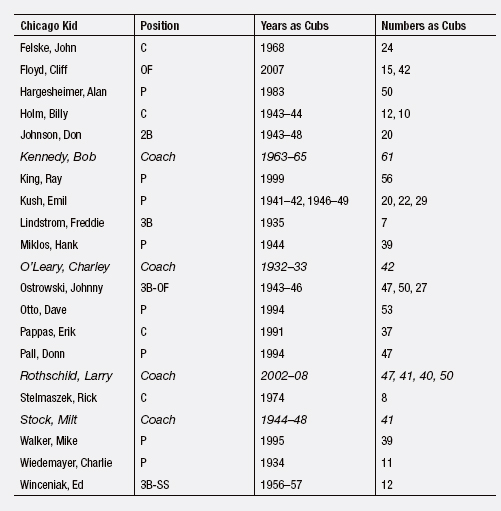

Native Sons by the Numbers

Native Son is the 1940 novel by Richard Wright about a young man from Chicago named Bigger Thomas who…well, we’ll hope your high school English teacher helped you sort that out. This sidebar is about young men born in the city of Chicago who grew up to be Cubs and the numbers that they wore. It does not include people born outside the city limits or players who moved to the Windy City as youths; nor does it include Cubs from before they started wearing numbers in 1932, though we’re all very proud of those native sons, too. Coaches who wore numbers, including “head coach” Bob Kennedy of the College of Coaches fiasco, are included (in italics) because a lot of kids grow up hoping they’ll one day find a great job near home.