#46: WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN, PART DEUX

| ALL-TIME #46 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Bill Fleming | 1942 |

| Marv Rickert | 1942 |

| Dom Dallessandro | 1943–44, 1946–47 |

| Bob Scheffing (coach) | 1954–55 |

| Ray Hayworth (coach) | 1955 |

| Ed Mickelson | 1957 |

| Joe Schaffernoth | 1959–61 |

| Al Lary | 1962 |

| Larry Jackson | 1963–66 |

| Dave Dowling | 1966 |

| Ken Johnson | 1969 |

| Steve Barber | 1970 |

| Juan Pizarro | 1970–73 |

| Pete Reiser (coach) | 1974 |

| Marv Grissom (coach) | 1975–76 |

| Dave Geisel | 1978–79 |

| Lee Smith | 1980–87 |

| Dave Pavlas | 1990–91 |

| Sammy Ellis (coach) | 1992 |

| Steve Traschel | 1993–99 |

| Oscar Acosta (coach) | 2000 |

| Jason Bere | 2001–02 |

| Dick Pole (coach) | 2003 |

| Ryan Dempster | 2004–12 |

| Scott Feldman | 2013 |

| Pedro Strop | 2013–15 |

The story of #46 is a twofold tale of “too late” and “too soon.” Of the nineteen players who have worn the number (plus six coaches), only three (Marv Rickert, Dom Dallessandro, and Ed Mickelson) have been position players—and none have worn it since Mickelson did so briefly in 1957.

But of the pitchers—oh, how a change here or there might have made this number famous. Or retired. Al Lary wore it for the awful 1962 Cubs (eight years after wearing #31, in 1954). He went 0–1, 7.15 in 15 appearances. If only instead of Al, the Cubs had his brother Frank, a four-time 15-game winner for the Tigers.

Larry Jackson won 24 games for the Cubs in 1964, the most any Cubs pitcher has won in a season (tied by Fergie Jenkins in 1971) since Pete Alexander’s 27 in 1920. But what if Jackson had been averaging 15 wins a year from 1957–62 for the Cubs instead of the Cardinals? Maybe they’d have had a chance to contend, particularly in 1959 when Ernie Banks had one of his two MVP seasons and the team finished only thirteen games out of first place. At least Jackson helped bring Fergie to the Cubs in the 1966 deal with Philly.

Dave Dowling was hyped as a pitching prospect after being acquired from St. Louis, and perhaps he could have joined Fergie, Bill Hands, and Kenny Holtzman in 1969 and beyond. But he only started one game for the Cubs, on September 22, 1966, a complete-game, 7–2 win, before leaving baseball to go to dental school. He now practices as an orthodontist in California.

Ken Johnson? Too late; five years after he threw the only nine-inning, complete-game, no-hit loss in major league history, he made nine decent relief appearances for the Cubs, then got released. Juan Pizarro? Too late; after pitching in the 1957 and 1958 World Series for the Milwaukee Braves at just barely drinking age and winning 61 games for the White Sox from 1961–64, the Cubs tried to catch lightning in a bottle by acquiring him from the Angels for Archie Reynolds. Pizarro was decent—going 7–6, 3.46 with three shutouts in 1971—but the Cubs still didn’t win.

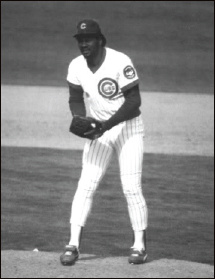

And that brings us to the #46 who could have had the number retired in his honor: Lee Smith (1980–87). Big Lee, a Louisiana native, stood 6-foot-5, threw hard, and wound up holding the major league saves record from 1993–2006. But at first the Cubs couldn’t figure out what to do with him. In 1982 he actually started five games. He eventually settled in as closer and he saved 33 games for the 1984 NL East champs; Smith repeated that number the next year. But by 1987, even though he tied what was then the club record with 37 saves, he blew 12 save chances and was being booed regularly. Jim Frey, who was out of his league after being promoted from dugout boss to general manager, supposedly rejected offers to trade Smith to the Dodgers for Bob Welch, and to the Braves for John Smoltz and Jeff Blauser (while the shortstop still had his best years ahead of him, rather than the ghost-Blauser the Cubs got in 1998). Instead, Frey shipped Smith to the Red Sox for Al Nipper and Calvin Schiraldi, neither of whom will ever make any top ten Cubs list (unless it’s a negative list). Smith, meanwhile, went on to have 298 more saves, including 18 against the Cubs (or 13 more saves than Schiraldi had in a Cubs uniform), and, though it’s a long shot, Big Lee may eventually make the Hall of Fame.

Big Lee Smith was the shutdown closer who came after Bruce Sutter but left Chicago too soon.

Steve Trachsel (1993–99) won’t make the Hall of Fame, but the Stall of Fame is a possibility for the deliberate—who are we kidding?—downright slow right-hander. He had one fine year in Chicago—1998—going 15–8 and winning the wild-card tiebreaker game against the Giants on September 28. Nationally, though, he’ll always be remembered for the pitch that year that Mark McGwire served over the fence in St. Louis for his 62nd home run. Trachsel later had several solid seasons for the Mets after the Cubs let him leave via free agency. When he returned to the Cubs in 2007 for a not-so-great encore (1–3, 8.31), he wore #52, as #46 had been taken for several years by Ryan Dempster (2004–12).

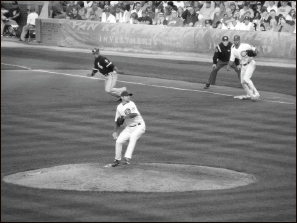

Starting or relieving, Ryan Dempster kept things exciting during almost nine Cubs seasons.

Dempster helped finally take the “too late” tag off #46, arriving in 2004 and staying until the rebuilding Cubs shipped him to Texas in July 2012. In that time he started 154 Cubs games, finished 183—leading the NL in games finished in 2006 and in starts in 2011—and had a 67–66 record with 87 saves, and an All-Star appearance.

During the 2007–08 offseason, Dempster let it be known that he wanted to try starting again, as he had enjoyed some success in that role with the Marlins (he made the All-Star team as a starter in 2000). He began a tough workout routine, including running up and down Camelback Mountain in Arizona, one of the toughest trails in that state, and it paid off—he once again made the All-Star team in 2008 and had the best record of his career, going 17–6 with a 2.96 ERA. Starting in 2008, he tossed over 200 innings each of the next four years. Good idea wanting to go back to the rotation.

Pedro Strop was involved in one of the better number swaps in recent memory. On July 2, 2013 the Cubs sent reliever Scott Feldman, wearer of #46, and outfielder Steve Clevenger to Baltimore for Strop, and the Orioles tossed in this other pitcher named Jake Something…Oh, yeah, Jake Arrieta. Feldman left Baltimore as a free agent after 2013 and Clevenger was a part-time Oriole until he was traded to Seattle after the 2015 season. Strop had an ERA under 3.00 while pitching at least 65 games for the Cubs in both 2014 and ’15. And that Arrieta guy—Cy Young winner in 2015 and author of two no-hitters—did all right, too.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #46: Ed Mickelson (1957). Mickelson had a couple cups o’ coffee with the two St. Louis teams, going 1-for-10 for the Cardinals in 1950 and 2-for-15 with the Browns in 1953. Those poor performances didn’t stop the Cubs from taking him north with the club in 1957, in the days when rosters could be larger than 25 for the first weeks of the season. Mickelson was an afterthought; he started two games and subbed in four others, going 0-for-12 and getting his only Cub RBI on a foul popup on which Ernie Banks scored.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #46: Steve Barber (1970). A hard and wild- throwing lefty (130 walks and 150 strikeouts in 1961), Barber won 101 games for the Orioles from 1960 through 1966, though he didn’t pitch in the O’s World Series sweep of the Dodgers. Like fellow #46 Ken Johnson, Barber threw a no-hitter and lost, though Stu Miller got the last out; and like a lot of hard throwers of that era, Barber got hurt. Without modern surgical techniques available, he drifted from team to team, trying to get back his old form. The Cubs signed him on April 23, 1970, and after five appearances and a 9.53 ERA, they released him on June 30. He managed to resurrect his career and have a couple of fine years as a middle reliever with the Angels in 1972 and 1973.

Save It

The save, an important modern statistic, is a Chicago invention. Chicago Tribune sportswriter Jerome Holtzman came up with the system that first quantified the late-inning reliever’s role and eventually led to many becoming wealthy men. The Cubs have been keeping track of saves since 1960 and Holtzman’s creation has been an official stat since 1969.

The Cubs have racked up a ton of saves in the last half century. Some numbers seem better equipped than others, or more accurately, have better pitchers who wind up wearing those numbers. Not surprisingly the two most successful Cubs closers of 1969–2015 correspond with the top three numbers on the chart:

1. Lee Smith #46 (180 career saves)

2. Bruce Sutter #42 (133)

| Uniform # | Saves |

| 46 | 280 |

| 42 | 167 |

| 28 | 164 |

| 49 | 144 |

| 38 | 110 |

| 45 | 106 |

| 32 | 95 |

| 36 | 70 |

| 47 | 68 |

| 39 | 65 |

| 27 | 64 |

| 43 | 64 |

| 48 | 63 |

| 63 | 56 |

| 41 | 55 |

| 56 | 55 |

| 34 | 50 |

| 51 | 45 |

| 33 | 42 |

| 37 | 34 |