#48: BIG DADDY AND HANDY ANDY

| ALL-TIME #48 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Whitey Platt | 1942–43 |

| Andy Pafko | 1944–51 |

| Gene Hermanski | 1951 |

| Jim Fanning | 1954 |

| Luis Marquez | 1954 |

| Jim King | 1955–56 |

| Jim Woods | 1957 |

| Jim Brewer | 1961 |

| Frank Baumann | 1965 |

| Joe Niekro | 1967–69 |

| Dave Lemonds | 1969 |

| Jim Colborn | 1969–71 |

| Rick Reuschel | 1972–81, 1984 |

| Dickie Noles | 1982–84 |

| Jay Baller | 1985–87 |

| Mike Harkey | 1988 |

| Phil Roof (coach) | 1990–91 |

| Dennis Rasmussen | 1992 |

| Mark Clark | 1997 |

| Dave Stevens | 1998 |

| Marty DeMerritt (coach) | 1999 |

| Ruben Quevedo | 2000 |

| Joe Borowski | 2001–05 |

| Scott Williamson | 2005–06 |

| Ryan O’Malley | 2006 |

| Neal Cotts | 2007–09 |

| Andrew Cashner | 2010–11 |

| Rafael Dolis | 2012–13 |

| Anthony Varvaro | 2015 |

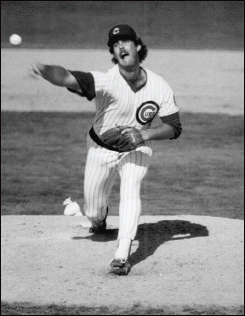

Rick Reuschel was a giant of a man (listed at 6-foot-3, 235, he may have been even heavier than that); in spite of that, he was an excellent athlete who was a good hitter (35 career doubles) and was occasionally used as a pinch-runner. This, despite being teased by his teammate Steve Stone, who once was asked how the clubhouse food spreads were when he played for the Cubs. His response: “I have no idea. I never had any, because there was always 500 pounds of Reuschels between me and the spread.”

Underestimated by management and undersupported by his teammates, Rick Reuschel was one of the best things to happen to the 1970s Cubs.

Younger brother of bespectacled, big-boned Cubs reliever Paul Reuschel, who debuted later and retired earlier than his sibling, Rick Reuschel reached the majors only two years after he was drafted in 1970. Reuschel went a respectable 10–8 with a fine 2.93 ERA in his rookie season, puzzlingly not getting a single vote in the 1972 NL Rookie of the Year balloting. (Jon Matlack won it for the Mets.)

The following year he began to define the term “workhorse.” From 1973 through 1980, Reuschel never pitched fewer than 234 innings, starting between 35 and 39 games each year. Even so, he was really no better than a .500 pitcher until 1977, when he and the rest of the Cubs roared out to a 48–33 start and an 8 ½-game lead in late June. On July 28, he was sent into the game against the Reds in relief in the 13th inning, and his base hit began a rally in the bottom of the inning; the pure-joy grin on his face as he scored the winning run on Davey Rosello’s single in a 16–15 victory is a singular memory for any Cubs fan from the 1970s.

After that win, Reuschel was 15–3 with a 2.14 ERA and was the odds-on favorite for the NL Cy Young Award. Needless to say, it didn’t happen—the team collapsed and despite pitching reasonably well the rest of the year, Rick wound up 20–10 and finished third in the Cy Young balloting behind Steve Carlton. It was the only 20-win season for a Cubs pitcher between Fergie Jenkins’s 24-win season in 1971 and Greg Maddux’s 20-win season in 1992.

By 1981, the Cubs had fallen to the depths of the NL, and Rick was off to a mediocre 4–7 start (though with a team that was 15–37 at the time, maybe that wasn’t so bad).Given the pressure to “do something,” GM Bob Kennedy traded him to the Yankees the day that year’s strike started. When the strike was settled, the Cubs received Doug Bird and a prospect named Mike Griffin, who never panned out. Bird was a marginally useful starting pitcher, and Reuschel went 4–4 for the Yankees in 11 starts, pitching for them in both the split-season 1981 division series, and the 1981 World Series. A torn rotator cuff ruined most of the next two years for Rick, but the Cubs re-signed him (he looked odd wearing #47 in 1983, but he reclaimed his familiar #48 the next season) and he contributed to the 1984 NL East champions, though he was disappointed to not be named to the playoff roster. They could have used him as the rest of the bullpen collapsed in the NLCS. Never a favorite of the Dallas Green regime, he was allowed to depart as a free agent after the 1984 season—and, fully recovered from arm surgery, he won 14 games for the Pirates in 1985, and later had a 19-win season for the Giants in 1988 and a 17-victory season in ’89, when he started—and won—the decisive Game 5 of the NLCS against his former team. That year he also started the All-Star Game in Anaheim and allowed the mammoth leadoff home run to Bo Jackson.

Andy Pafko (1944–51) patrolled the outfield at Wrigley Field for more than eight seasons. The Wisconsin native, purchased in 1941 from Green Bay in the Wisconsin State League, was in the major leagues less than two years later (wearing #33 at the end of the 1943 season) and batted .379 as a call-up. He was installed in center field the following year and had a nice rookie season. Pafko helped lead the Cubs to the pennant in 1945 with 12 HR (that may not sound like many today, but league-leader Tommy Holmes had only 28), 110 RBI (good for third in the league), and a .298 average; he finished fourth in the NL MVP voting. He continued to put up solid seasons for the Cubs as the team free-fell to the bottom of the NL standings. Pafko was named to the All-Star team five times in six years, including 1948, his only year in the majors as a regular third baseman. He hit a career-high 36 homers in 1950 as the Cubs finished seventh.

The next year, inexplicably, management, perhaps wanting to shake up a moribund franchise, traded the still-in-his-prime Pafko to the Dodgers in an eight-player deal. None of the players acquired matched the performance or popularity of Pafko. Meanwhile, Handy Andy settled right in to left field with the Dodgers, where he achieved photographic immortality for the wrong reason. He was the outfielder looking dejectedly at Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round The World” at the Polo Grounds on October 3, 1951.

Pafko played in three more World Series—with the Dodgers in 1952 and his home-state Milwaukee Braves in 1957 and 1958, but, in his own words quoted in The Sporting News of June 27, 1951, his biggest thrill in baseball came much closer to home:

“It was 1945 and the Cubs were battling for the pennant. It was the next-to-the-last week of the season and the Pirates were at Wrigley Field. It was a Saturday and the fans were giving me a day. My mother and father had come down from Wisconsin to see me play. My mother had never seen me play before. I never wanted to hit one so much in my life. Preacher Roe was pitching for the Pirates. My first time up I found the bases loaded. I guess I was trying too hard, because Preach struck me out. But I was lucky. I got another chance. The next time up the situation was exactly the same. The bases were loaded again.

“This time I didn’t miss. I hit one into the stands and I don’t think I’ll ever have another thrill like that one. Looking back now, it’s even bigger. Because that was the only time my mother ever saw me play. She’d never seen me play before and she was never to see me again. She died a couple of years ago without ever getting another chance.”

Many times, ballplayers get the details wrong but this one, Pafko got right, except for the day of the week (it was Sunday, not Saturday). He hit what the Tribune termed “a four-run homer” and the Cubs beat the Pirates, 7–3.

The 1950s produced a bunch of mediocre hitters at #48: Gene Hermanski (1951), who came over from Brooklyn in the eight-player deal, took over Pafko’s number but didn’t hit like him; Jim Fanning (1954) had a better career as an executive (and he managed the only postseason games ever played by the Montreal Expos); Luis Marquez (1954); Jim King (1955–56), who later hit 89 homers in six and a half seasons with the expansion Senators in the 1960s; and Jim Woods (1957), who was signed out of Chicago’s Lane Tech High School, like Phil Cavarretta a generation earlier, but who played only two games for the Cubs.

After Woods’s brief appearance in #48, it became exclusively a pitcher’s number, specializing in has-beens: Frank Baumann (1965) and Dennis Rasmussen (1992), who won 91 major league games in 12 seasons—all of them for other teams (0–0, 10.80 in three Cubs appearances, and he is no relation to a current Chicago Blackhawk of the same name. Baseball’s Dennis was born in California, while the NHL version hails from Sweden). And there were never-weres: Dickie Noles (1982–84), Jay Baller (1985–87), who had a great fastball but no idea where or how to throw it, Dave Stevens (1998), and Ruben Quevedo (2000), who had a good repertoire but ate his way out of baseball; and guys who had better careers elsewhere: Jim Brewer (1961; Brewer also wore #38 and #45), Jim Colborn (1969–71), who went 4–2, 3.78 in three brief Cubs callups, became the first 20-game winner in Milwaukee Brewers history in 1972, and Mark Clark (1997; Clark switched to #54 in 1998). Ryan O’Malley (2006) pitched in only two major league games, but his first, on August 16, 2006, was memorable. Called up from Triple-A on only a few hours’ notice after the Cubs had played an 18-inning night game in Houston, he was driven by limousine from the Iowa Cubs’ road trip in Round Rock, Texas early the next morning; he threw eight five-hit, shutout innings against the Astros in a 1–0 victory, one of the few highlights of the misbegotten 2006 season. Six days later at Wrigley Field, he took the field to a standing ovation against the Phillies, and after allowing three runs in 4.2 innings, he left the major league field, never to return.

Jay Baller was a ballplayer who gave his all on every pitch.

Neal Cotts (2007–09) took over the number after coming over in a rare trade with the White Sox. The crosstown deal (for David Aardsma and Carlos Vasquez) was just the second since the legendary 1992 Sammy Sosa heist. Cotts never had a win or a save in 85 games as a Cub, but the lefty who grew up in Lebanon (that’s Illinois), specialized in getting one out at a time. His best year as a Cub was for the 2008 division champs.

One other #48 who deserves mention is Joe Borowski (2001–05). “Lunch Bucket Joe,” signed almost as an afterthought by the Cubs out of the Mexican League in 2000, was brought to the majors for one start in 2001, replacing Kerry Wood, who had to skip a start. Borowski wound up giving up Barry Bonds’s 50th homer of the season and took the loss while giving up six runs in less than two innings. It was his only major league start. Working hard, he came back the next year as a reliever and in 2003 saved 33 games for the NL Central champions. In 2004, his performance declined and it took two months before he admitted to a shoulder problem. He had surgery and came back a year later, but, inexplicably, the Cubs let him go. He wound up having solid years for the Marlins in 2006 (36 saves) and for the 2007 AL Central champion Indians, leading the AL with 45 saves despite a 5.07 ERA. It’s Joe’s bulldog attitude and work ethic that will always make him a fond memory for Cubs fans.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #48: Dave Lemonds (1969). Lemonds, drafted out of the University of North Carolina in the first round of what was then termed the “secondary phase” of the 1968 draft, was deemed “ready” in June 1969 and so, at age twenty-one, he was recalled to start a game in Montreal against the Expos. Lemonds gave up four hits, three walks, and two runs in 2.2 innings and was the losing pitcher in a 5–2 Cubs loss, but that wasn’t the story of the game, which was delayed two hours by a torrential rainstorm. In the second inning Ernie Banks hit what appeared to be a home run. Expos outfielder Rusty Staub, taking advantage of the poor field conditions and visibility (the game probably shouldn’t have been played at all, as there was an afternoon game scheduled the next day), told umpire Tony Venzon that the ball had gone under the fence at Parc Jarry. Venzon believed Staub and despite an angry tirade from Leo Durocher, the play stood as a ground-rule double; Banks advanced to third base on a flyout, but wound up stranded. Durocher played the game under protest, but as in most of those situations, the protest was denied. As for Lemonds, he threw two scoreless innings of relief against the Cardinals five days later, and eventually he was traded to the White Sox in a five-player deal. And Banks is still out that 513th home run, thanks to not-so-trusty Rusty.

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #48: Joe Niekro (1967–69). Phil’s younger brother had a twenty-two-year major league career in which he won 221 games (combined with Phil, they had a brother-record 539 wins). Unfortunately for Cubs fans, only 24 of those wins were in the blue pinstripes. Joe, off to a slow start in 1969 after good years in ’67 and ’68, was shipped to the Padres for Dick Selma, who became popular for leading the Bleacher Bums in cheers but who spent only one year in a Cubs uniform, while Niekro was putting together two decades of pitching, winning 197 games in other uniforms and appearing in the postseason three times, including two scoreless innings in the World Series for the champion 1987 Twins.

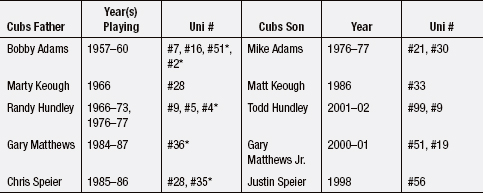

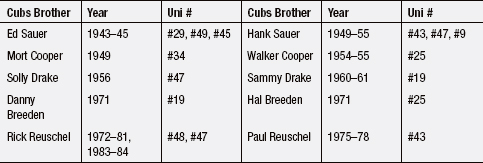

Boy, the Way Hank Sauer Played

This “All in the Family” segment features Cubs father-son and brother combinations and the numbers they wore. It’s a pretty nondescript bunch, with the Sauer, Matthews, Hundley, and Reuschel clans the only ones on anyone’s Christmas card list. Out of respect, we’ll also mention the Cubs family pairs that played before there were numbers: father and son Jimmy Cooney, plus Herm and Jack Doscher (the former appeared as a Cub in 1879). Larry and Mike Corcoran were the first fraternal teammates in Cubs history in 1884. They were followed by Jiggs and Tom Parrott in 1893 and Kid and Lew Camp in 1894.

Of the number-wearing families, Todd Hundley was the only son to wear his father’s number (and he had to wear another number until that became available). Four of the five fathers in the list below went on to coach for the Cubs (Marty Keough being the lone exception) and an asterisk is placed next to the number they wore as coaches. Bobby Adams wore #51 as a coach in 1961–65 and #2 while coaching in 1973. Randy Hundley was a player-coach wearing #4 in 1977. Gary Matthews was a coach wearing familiar #36 (2003–06). Chris Speier wore #35 as a coach (2005–06). None of these four got to coach their sons in Chicago.

The Breedens and Reuschels are the only number-wearing brother combos to be Cubs teammates.