#49: ARRIETA, ETCETERA

| ALL-TIME #49 ROSTER: | |

| Player | Years |

| Carroll Yerkes | 1932 |

| Vince Barton | 1932 |

| Stan Hack | 1933 |

| Kirby Higbe | 1937 |

| Ed Sauer | 1944 |

| Frank Secory | 1944–46 |

| Ed Hanyzewski | 1946 |

| Ray Mack | 1947 |

| Bill Baker (coach) | 1950 |

| Charlie Root (coach) | 1951–53 |

| Steve Bilko | 1954 |

| Bill Hands | 1966–72 |

| Jim Kremmel | 1974 |

| Donnie Moore | 1975, 1977–79 |

| Rawly Eastwick | 1981 |

| Tim Stoddard | 1984 |

| Steve Engel | 1985 |

| Jamie Moyer | 1986–88 |

| Frank Castillo | 1991–97 |

| Kennie Steenstra | 1998 |

| Felix Heredia | 1999–2001 |

| David Weathers | 2001 |

| Will Cunnane | 2002 |

| Jimmy Anderson | 2004 |

| John Koronka | 2005 |

| Carlos Marmol | 2006–13 |

| Jake Arrieta | 2013–15 |

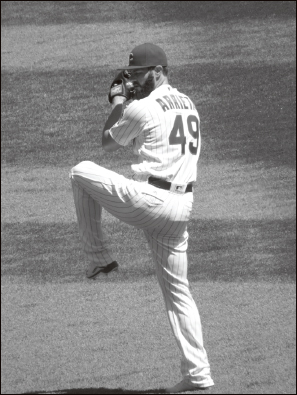

The lot of the 49er, for the most part, has been to pitch. And the current owner of the number is the best of the bunch. Jake Arrieta was acquired from the Orioles in July 2013 for Steve Clevenger and Scott Feldman. He cut his ERA in half, 7.23 in Baltimore to 3.66 in Chicago that summer. The next year he sliced 1.13 off that ERA and won 10 times.

In 2015 he had 22 wins, logged a “Three Finger” Mordecai Brown-esque 1.77 ERA, tossed the first of two no-hitters, and became the first Cub since Greg Maddux in 1992 to win the Cy Young. And in the one-game wild card playoff game in Pittsburgh he tossed a complete-game shutout after leading the NL in both those categories during the season. Oh, and besides his rapid ascent to the upper echelon of baseball’s best pitchers, he may also sport the game’s best beard. Yet at last look, his Twitter handle still had his old Orioles number: @JArrieta34. It might be safe to change that username now.

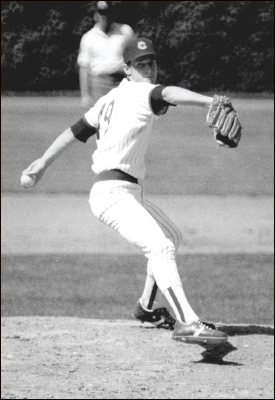

Jake Arrieta shares a number with the journeymen but has the poise of an elite pitcher.

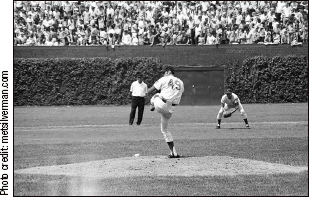

Bill Hands (1966–72) was on the other end of the spectrum. Clean cut, not flashy, and a control pitcher who was a swingman until becoming a rotation mainstay in 1968, Hands wasn’t the first pitcher you thought of when Leo Durocher’s Cubs came to town. On a roster that included future Hall of Famer Fergie Jenkins and hard-throwing lefty Ken Holtzman, Hands was sometimes an afterthought, but he helped complete a formidable staff. Hands came to the Cubs with Randy Hundley in a heist from San Francisco in December, 1965. (Lindy McDaniel and Don Landrum went west in exchange.) In 1968 he won 16 games and walked the fewest batters in the league per nine innings, although he also led the NL in homers allowed. He won 20 games and threw 300 innings in ’69, and Jenkins still led the club in both categories. Hands’s 2.49 ERA, however, led the team. He won 41 games over the next three seasons, but his ERA was 3.00 or higher each season. In 1972 the Cubs traded Hands and two youngsters to Minnesota for lefty Dave LaRoche. While his pitching skills slipped in the AL, Hands benefited from the advent of the designated hitter in ’73 as his putrid batting average could go no lower than .078. His lack of batting prowess was legendary among his Cubs teammates, and at one time Ron Santo had a standing bet that Hands would never hit a home run. On September 4, 1970, when Hands hit a long fly ball to center field at Wrigley Field against the Mets, Santo found himself rooting for the ball not to go out of the park, even though the game was tied at the time. It didn’t—Hands settled for a double, one of only six in his career. The Cubs did win the game, 7–4, though Hands did not get the victory after being pinch-run for following his unlikely double.

Bill Hands piled up innings and wins for the Cubs in the 1960s.

Of the twenty-seven Cubs to don the number, two were coaches, nineteen were pitchers, and six position players, but no non-mound man has worn it since Steve Bilko (1954), a huge man (6-foot-1, 230 pounds) for his time who would hit monstrous home runs and also strike out monstrously. (He’d have made a perfect DH had they had them in those days.) The Cubs bought him from the Cardinals early in the 1954 season and didn’t quite seem to know what to do with him. For several seasons he bounced up and down between the Cubs and their then-top farm team in the Pacific Coast League, the pre-major league LA Angels. He dominated the PCL, hitting 148 homers from 1955–57 and winning the league Triple Crown in 1956 when he hit .360 with 55 HR and 164 RBI. But he played only 47 games for the North Siders, hitting .239 in 92 at-bats with four homers. He’d have been a natural hitting in Wrigley Field in the 1950s. Eventually Bilko went to the major league Angels in the expansion draft, and, ironically, hit the last home run in Wrigley Field—but not in Chicago; that blast was hit in Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, the Angels’ first major league home, in 1961.

Vince Barton (1932) was the first #49, starting in right field the first day the numbers were handed out. His batting numbers—.224/.273/ .351—quickly put that uni number into circulation. Carroll Yerkes later that year became the first pitcher to wear it, followed by young third baseman Stan Hack (1933), who went through eight numbers in a career that kept him in a Cubs uniform, as a player, coach and manager, into the mid-1960s.

Kirby Higbe (1937) wore #49 on his first recall to the Cubs at age twenty-two. As was customary for young, unproven players, he was assigned different numbers in his other two years with the Cubs: #25 in 1938 and #29 in 1939, the only full season he spent in a Cubs uniform (not a very good one: 12–15 in 43 games, 28 starts, with a 4.67 ERA). Higbe went on to a solid career, mostly with the Dodgers, and pitched for them in the 1941 World Series. He left the Cubs in one of the better deals they made in that era: traded to the Phillies on May 29, 1939, along with Joe Marty and Ray Harrell, in exchange for Claude Passeau, who would become a mainstay in the Cubs rotation for most of the 1940s.

Frank Secory (1944–46) had 156 at-bats as a part-time outfielder for the Cubs between 1944 and 1946, hitting .237, and went 2-for-5 in the 1945 World Series. Even at that, he wouldn’t really be worth a mention here except that in 1952 he became a National League umpire, calling games for nineteen seasons and umpiring in four World Series.

Frank Castillo (1991–97) had a promising 10–11, 3.46 season at age twenty-three in 1992, but was then beset by injuries and never really made it. His shining Cubs moment was a near no-hitter thrown against St. Louis on September 25, 1995; it was broken up with two outs in the ninth by a Bernard Gilkey triple. Castillo also had 13 strikeouts that night.

Jamie Moyer (1986–88), a sinkerball, Tommy John-style lefty, looked good but was traded away in the Mitch Williams deal, a trade that helped the Cubs to the 1989 NL East title. No one could have guessed that #49 for the Cubs would still be pitching at age forty-nine in 2012. He would have a 269–209 record, making the All-Star team and earning 20 wins for the first time at the age of forty, and finally reaching his first World Series in his twenty-second major league season in 2008. In 2012, just months shy of turning fifty, Moyer was released by three teams, which is understandable, but three clubs also cut him in just over a year in his twenties: the Rangers, Cardinals, and Cubs, who signed him back before the 1992 season and then released him at the end of spring training—but not before offering him a minor league coaching job. Moyer thanked the Cubs but told them he thought he could still pitch. Guess he was right.

So #49 went to guys who were World Series heroes with other teams (Rawly Eastwick, 1981, a hero for the 1975–76 Reds); guys who had been on NCAA college basketball championship teams (Tim Stoddard, 1984, a member of the 1974 North Carolina State Wolfpack); or never-wases-and-never-will-bes (Steve Engel, 1985; Will Cunnane, 2002; Jimmy Anderson, 2004, and John Koronka, 2005). And then along came Carlos.Carlos Marmol took over the #49 longevity mark from Hands and Castillo, spending eight seasons in the number (2006–13). Marmol and his electric slider took Chicago by storm, with an All-Star appearance in the setup role in 2008, successive 30-save seasons, and then…you’ve seen this before. Relievers aren’t forever, the electricity can drain from a slider like a sturdy oak branch taking down a telephone pole. It is impressive that a short reliever held down #49 longer than anybody.

Soft-throwing southpaw Jamie Moyer still had a couple decades—and a couple hundred wins–left in that arm after the Cubs cut him in 1992.

MOST OBSCURE CUB TO WEAR #49: Kennie Steenstra (1998) was one of the Cubs’ better pitching prospects in the 1990s, but he never got a real opportunity to prove himself in Chicago. He toiled for seven seasons in the farm system, winning 66 games before getting a token opportunity in four games early in the 1998 season. (We’re wondering about the spelling of “Kennie,” too. What’s up with that?)

GUY YOU NEVER THOUGHT OF AS A CUB WHO WORE #49: Donnie Moore (1975–79) had four decent years as a middle reliever, starting one game each year, but the Cubs in those years had plenty of good relief pitchers. They dealt him to the Cardinals for Mike “Not the Fighter” Tyson. Later, of course, Moore gave up a devastating home run in the 1986 ALCS, said to have unhinged him and led to his eventual suicide.

Clown College

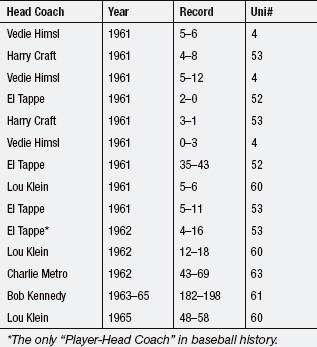

The College of Coaches was the poster child for bad ideas from the mind of owner P.K. Wrigley. In the first ninety years of the franchise’s existence, dating back to the National Association in 1871, the franchise had never lost more than 94 games in a season. Two years into the College—and the 162-game schedule—the Cubs got an F, or the baseball equivalent of that grade: their first 100+ loss season, a 59–103 mark.

Wrigley had announced the system to a skeptical press by saying, “The dictionary tells you a manager is the one who bosses and a coach is the one who works. We want workers.” They may have had workers, but the system never worked. First of all, few coaches with managerial options or aspirations would go anywhere near the Cubs. (Though Harry Craft did go from the 1961 College of Coaches to manager of the first-year Houston Colt .45s, who would finish ahead of the ’62 Cubs.) Second, Wrigley could replace head coaches even quicker than he did managers—and only seven years earlier he had fired popular and honest Phil Cavarretta while the team was still in spring training. Third, not all coaches got chances to be head coach; most lamentably Buck O’Neil, who was baseball’s first African American coach and could have been the first manager of color. (It took thirteen more years for that barrier to be broken, by Frank Robinson in Cleveland.) O’Neil, a championship manager in the Negro Leagues, getting a chance to lead the Cubs? Now that would have been innovative.

The College of Coaches experiment continued, though Bob Kennedy ran the team on the field for the next two-plus seasons. The Cubs showed an improvement of twenty-three games and had a winning season in ’63. Kennedy was eventually replaced in June 1965 by Lou Klein, who had twice previously served as head coach. Leo Durocher was brought in the next year to clean up the mess, stating, memorably, at his introductory press conference: “If no announcement has been made about what my title is, I’m making it here and now. I’m the manager. I’m not a head coach. I’m the manager.” Starting from scratch, the Cubs again lost 103 games. They followed with a winning record each of the next six seasons. No Cubs team has put together that many consecutive winning seasons since Leo.

Here’s the rundown by the numbers of College of Coaches in order of P.K.’s whim.