THE MODEL READER AND THE MUNDANITY OF READING PRACTICES

Umberto Eco’s theory of reading is usually referenced to his earlier writings in The Role of the Reader, his Italian Lector in fabula (unfortunately never fully translated into English), and The Limits of Interpretation.1 In those writings Eco describes how a text anticipates and directs its interpretations. He explains this working of a text by distinguishing between what he calls the “model reader” and the “empirical reader.” In elucidating the notion of the model reader, Eco talks about the interpretive paths that a text indicates for its readings. The empirical reader, on the other hand, primarily serves the rhetorical function of a contrastive element; in other words, Eco’s interest is not directed toward actual acts of engaging a text.

Eco’s later writings further develop this theory.2 Even if not specifically dedicated to the discussion of reading, those texts are of interest as they provide openings toward embodiment and the situatedness of reading practices. Here I foreground this dimension to explore possible intersections between Eco’s theory of reading and the mundanity of reading practice. I discuss an example from apprenticeship in scientific practice to suggest that attending to the empirical reader should not direct us away from deciphering strategies for reading inscribed in a text. Approached in such a manner, the model reader shows up as enacted across the text and its empirical readers, dynamically reconfigured relative to the specificity of the situation of reading in which it is instantiated.

I. THE MODEL READER

According to Eco’s writings on textual semiotics, every text is incomplete.3 Since not everything that constitutes a reading is present at the expressive surface of the text, the text needs its readers’ cooperation to gain its meaning. As the work of reading takes place, the reader fills in the blank spaces, completing what is left unsaid, what is implied, or what was mentioned earlier in the text. In a similar vein, the reader also connects the surface of the text with prior texts and those texts that will follow from it. Eco speaks of text as “a lazy machine that demands the bold cooperation of the reader to fill in a whole series of gaps” of unsaid or already said missing elements.4

In the 1970s, when Eco ushered the reader into the world of textual analysis, the implications were radical. If meaning is not a property of a text taken in isolation, it is legitimate to ask what the text is. By arguing for the interpretive cooperation as an intrinsic part of the text, Eco’s vision of the text expands: the meaning of a text is now pushed to the interstices, where the written or vocally emitted signs collide with their possible interpretations. Thus, to understand how the text functions, we must take into account when and how the text can be interpreted. This implies a questioning of the textual autonomy so dear to structuralists. In The Role of the Reader, Lector in fabula, and The Limits of Interpretation, Eco quotes at length an interview with Claude Lévi-Strauss from 1967 in which Lévi-Strauss expresses his contempt for this new turn of attention away from the text taken in isolation. Lévi-Strauss claims that a work of art is

an object endowed with precise properties, that must be analytically isolated, and this work can be entirely defined on the grounds of such properties. When Jakobson and myself tried to make a structural analysis of a Baudelaire sonnet, we did not approach it as an “open work” in which we could find everything that has been filled in by the following epochs; we approached it as an object which, once created, had the stiffness—so to speak—of a crystal; we confined ourselves to bringing into evidence these properties.5

As the quote indicates, Eco’s move signals an abandonment of the goal to isolate the rules for the production of a text that can be understood independently of its effects (typical of the generative theories). However, Eco did not upset the structuralist doctrine by taking into account the actual acts of reading. In other words, when he advocates the interpretive contribution of the reader, Eco is not interested in individuals who read the text. Instead, his intervention is an invitation to go beyond the “objective” structure of the text available at the textual surface: rather than focusing on manifest meaning, Eco invites an exploration of how the text organizes its interpretations. By providing indices that guide readers’ inferences, the text anticipates, directs, and even demands specific interpretations.

To unpack Eco’s proposal, it may be instructive to consider the experiment performed by John Bransford and Marcia Johnson in 1972—even though the experiment is a foray away from textual theory and definitely not a part of Eco’s argument. In their experiment Bransford and Johnson used textual examples such as the following:

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, that is the next step; otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell. After the procedure is completed, one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more, and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.6

After presenting the subjects of their experiment with this passage, Bransford and Johnson checked the subjects’ comprehension and recall of information. A key piece of context had been withheld from some subjects, namely, its topic. The paragraph was about doing laundry. Those participants who were presented only with the paragraph but were not told that it was about doing laundry before they heard it, had a much harder time making sense of and remembering ideas from the passage. Their difficulty with this passage did not derive from their lack of knowledge regarding the meaning of the words used or their unfamiliarity with the sentence structure employed in the paragraph. Instead, the difficulty arose from the lack of the relevant contextual knowledge. Bransford and Johnson claim that such knowledge is a prerequisite for comprehending prose paragraphs.7 Knowing the topic helped the participants make sense of the paragraph, and this allowed them to remember more about it.

From that, Bransford and Johnson hypothesize that the information their subjects use may stem from putting together bits from several related sentences while also potentially including information that is not directly expressed in the paragraph.8 According to the authors, that information must derive from greater context: “Many sentences provide cues that allow one to create contextual structures that are sufficient for processing sentences seemingly in isolation. In other cases one will need additional information such as that built up by perceptual context or previous linguistic context in order to comprehend.”9

In his approach to reading Eco looks at how exactly this functions. He is on a quest to find out the mechanisms by which the text allows the reader to accomplish acts of meaning-making. In his attempt to understand the cooperative activity between the reader and the text, Eco’s interest is in how the reader can identify what the text does not explicitly say, but presupposes, promises, or implies. These competencies are not internal elements relative to the psychology of an individual reader, but, rather, are generated through the work of signs and are publicly available via the architecture of the text.

In accordance with a larger trend in the semiotics of text that characterizes European semiotics of the 1970s (for example, Kristeva, Barthes, Greimas, and Petöfi), Eco’s discussion of how literary texts generate meaning focuses on sign structures.10 Consequently, Eco’s explanations do not resort either to authors’ intentions or to any actual instances of reading. Since he is not interested in adding extra textual elements to his analysis of the text, Eco does not investigate responses of actual readers, as Bransford and Johnson in the study cited above do. More generally, Eco’s argument is different from approaches in either experimental psychology (where the focus is on how an individual mind processes information) or ethnomethodology (where we want to know how the work of reading is accomplished; for example, Livingston).11 Instead, in bringing forth the role of interpretive cooperation, Eco focuses on how the text itself organizes its expected readings. Rather than looking at how a text is actually interpreted, Eco is interested in the character of semiotic conventions.12

In this sense, the reader—as an active part of the interpretive process—is an element of the text itself. This reader-in-the-text is what Eco calls the model reader. In other words, the model reader is an abstract element constituted by the text. As such, it refers to structural characteristics of the text that encourage but also regulate its interpretations. To identify the model reader, the analyst is expected to focus on the internal coherence of the text and the cultural knowledge that the text presupposes since these elements point out how the text itself inscribes its instructions for reading and what kinds of interpretive interventions it “expects.” The model reader is thus a way to establish how and in what conditions the empirical reader is authorized by a text to collaborate. It is a textual feature that allows the empirical reader to actualize that which virtually exists in the terms manifested at the surface of the text.13 Obviously, each empirical reader is free and often does accomplish readings that do not coincide with what the model reader indicates. Nevertheless, every text exercises control over its interpretations because, at the level of expression, it provides indices for its expected readings. These inscriptions of the preferable interpretive paths are also discussed by Eco in terms of “the limits of interpretation.”14

Eco’s Italian Lector in fabula evokes Roland Barthes’s discussion of how reading generates pleasure.15 However, Eco insists that his interests are not oriented in the direction of the phenomenological aspects of reading. Rather, he wants to establish what it is in the text that stimulates and regulates interpretations.16 In choosing between studying the pleasure of the text and how this pleasure is generated by the text, in 1979 Eco explicitly sides for the second.17

II. PHENOMENOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF READING: TWO EXAMPLES FROM ECO’S LATER WRITINGS

Despite this commitment to textual structures, Eco’s later writings point to openings in the direction of empirical readers and their phenomenological positioning in the reading field. In order to indicate how this blurring of the boundary between textual workings and experiential aspects of reading may take place, I discuss two examples from Eco’s later writings. The first example—centered on olfaction—discusses the problem of iconicity, and the second one is on the textual production of space in verbal, visual, and aural texts. While the first concerns perception more generally, the second is explicitly centered on reading.

I start with Eco’s example about a visit to a perfume factory. This example is used as a part of Eco’s discussion of iconicity in Kant and the Platypus, intended as a revision of his original—what he calls “iconoclast”—position. In the 1960s and 1970s semioticians argued against iconicity as a naïve idea of similarity characteristic of our intuitive understanding of visual images (Barthes, Eco, Volli).18 When analyzing realistic drawings, cinematic images, and magazine advertisements, semioticians highlighted cultural and conventional aspects of those signs. In Kant and the Platypus Eco laments that even though, since the peak of the debate, many have been influenced by Peirce’s semiotics, that influence is concerned primarily with the notion of unlimited semiosis, leaving the theorizing of iconism largely unexplored.19 To deal with this neglect, Eco directs attention toward Peirce’s suggestion that iconic signs generate “effects of similarity.” While Eco, with Peirce, maintains that the interpretation of the iconic sign contains a perceptual basis,20 the anchoring of the sign in the material world does not mean, however, that an iconic sign should be equated with the iconic nature of perception. To deal with the immediate impression of likeness that iconic signs generate, Eco talks about “surrogates for perceptual stimuli.”

Eco evokes a perfume factory visit to prove that—even if under certain conditions a sign generates effects of similarity—we have to acknowledge that such impressions are relative to the surrogates manufactured to generate the effects. Experiencing the manufacturing of a perfume highlights the difference between a perceptual iconism and an impression achieved by way of surrogate stimuli:

Anyone who has ever visited a perfume factory will have come up against a curious olfactory experience. We can easily recognize (on the level of perceptual experience) the difference between the scent of violets and that of lavender. But when we want to produce industrial quantities of essences of violets or lavender (which must produce the same sensation, albeit a little enhanced, stimulated by these plants), the visitor to the factory is assailed by intolerable stenches and foul odors. This means that in order to produce the impression of the scent of violets or lavender, one must mix chemical substances that are most disagreeable to the olfactory sense (even though the result is pleasant). I am not sure nature works like this, but what seems evident is that it is one thing to receive the sensation (fundamental iconism) of the scent of violets and another thing to produce the same impression. This second operation requires the application of various techniques with a view to producing surrogate stimuli.21

To figure out the methods that generate the impressions of similarity, Eco refers to the observer whose positioning makes the constructed character of the iconic sign obvious. A visitor to the perfume factory has a different olfactory experience than a customer buying a perfume in a department store. Similarly, we can experience a painting as veridical only if we stand at a certain distance from it; if we move too close, the illusion of reality disappears.

This means that the surrogate stimuli partly depend on the way in which we engage with them: in the perfume factory versus in the department store, too close to the painting versus at a certain distance from it.22 Thus, to discuss the problem of iconicity, Eco’s example indicates that we should consider the acts of perception as essential elements in the functioning of the sign. If the notion of a text can be stretched beyond the literary texts, as Eco seems to indicate,23 then a reading of an olfactory text (for example, a perfume) and a visual text (that is, a painting) is importantly accomplished through an embodied and worldly positioning of their readers.

The second example that challenges the presupposition that Eco’s idea of reading is bound to textual borders comes from his discussion of space in literature in “Les Sémaphores sous la pluie” (reprinted as a chapter in On Literature). Eco analyzes hypotyposis, a rhetorical device employed to verbally render space. While it may be difficult to explain what hypotyposis is, Eco points out that the workings of this rhetorical figure are often successfully rendered through examples.24 Even though the illustrations that Eco provides—for example, Quintilian’s description of the invasion and sacking of a city—use a variety of descriptive and narrative techniques, they all allow the addressee, if willing, to draw a visual impression from them.25

Eco lists denoting, detailed description, listing, accumulation, and description appealing to the addressee’s personal experience as techniques through which hypotyposis can be developed.26 Even if this may be so to a lesser degree in denoting, all of the techniques require an active involvement of the reader. While hypotyposis—differently from other rhetorical figures such as metonymy, metaphor, and synecdoche—cannot be reduced to a formula or a rule,27 its effects are realizable if the reader collaborates. For hypotyposis to work, the reader has to translate what the text indicates into a visual scene, to experience various arrangements of objects, actions, and moments in time. Eco states that hypotyposis is “not so much a representation as a technique for eliciting an effort to compose a visual representation (on the reader’s part).”28 What does this mean for the postulate of intentio operis?

Let’s consider one of the techniques that generate hypotyposis: the description appealing to the addressee’s personal experience. Eco explains that “this technique requires that the addressee bring to the discourse something he has already seen and suffered. This activates not only preexisting cognitive schemes but also preexisting bodily experiences. . . . Part of this technique involves the evocation of introceptive and proprioceptive experiences on the part of the addressee.”29 As an example, Eco uses a quote from Blaise Cedrars’s Prose du transsibérien:

Toutes les femmes que j’ai rencontrées se dressent aux horizons

Avec les gestes pitieux et les regards tristes des sémaphores sous la pluie . . .

All the women I have met rise up on horizons

With the piteous gestures and sad looks of signals in the rain . . .30

To see the signals along the railroad track as they slowly disappear in the rainy night, the reader has to evoke the experience of watching through the window of a slowly moving train. Eco grants that one does not need to have a specific memory of the exact event to which to refer: we are well able to evoke experiences that are not even human (the example is the movement of fog through streets of London). The point, however, is that the text needs the embodied and lived experiences of the reader to be realized (no matter how imaginative and nonspecific these experiences may be).

Curiously, however, Eco wraps up his discussion of hypotyposis with an example from Beati, the commentaries to Revelation, where he explains a failed hypotyposis in terms of a lack of cultural knowledge. The example concerns the difficulty of the Mozambique miniaturists in representing the four living creatures as “above and around the throne.” Eco explains that

this is because the miniaturists, having grown up using the Greco-Christian translation, thought that the prophet “saw” something similar to statues or paintings. But the culture of John the Apostle, like that of Ezekiel, from whose vision John drew inspiration, was a Hebraic culture, and moreover his was the imagination of a seer. Consequently, John was not describing pictures (or statues), but, if anything, dreams, and, if you like, films (those moving pictures that allow us to daydream, or in other words, visions adopted from the layman’s state). In a vision that was cinematic in nature, the four creatures can rotate and appear at one moment above and before the throne, at another around it.31

While this example is no doubt revealing, it appears that it is not fully comprehensive of the argument presented in the piece. If hypotyposis allows the reader not only to envision space and elements of space through words but also motivates the reader to experience these visions as though they were personal, then a failure to enact the figure cannot be fully explained in terms of cultural knowledge.

One of the central components in the architecture of the original argument for the model reader is the concept of encyclopedia. Encyclopedia is an exhaustive record of the world knowledge that a culture possesses. Eco describes it as an ideal library or universal archive that gathers all information virtually obtainable in a given historical moment. Different from the dictionary, “encyclopedic representation excludes the possibility of establishing a finite set of metasemiotic features and makes the analysis potentially infinite.”32 This potential openness is only bounded by the existence of other texts since encyclopedia is but a sum of other texts (in the form of macropropositions).33 The encyclopedia-like semantics is also paralleled with the models of meaning representation in forms of schemas, frames, and scripts championed by artificial intelligence.34

Even though Eco has largely worked with the concept of encyclopedia when describing the strategies of reading—that is, the meaning of terms that the reader encounters being inscribed in the form of encyclopedic knowledge that a given culture possesses—I suspect that his initial characterization of encyclopedia is not broad enough to cover the vastness of the field that his writing covers. While the model reader is defined in terms of cultural knowledge and references to other texts, some of Eco’s examples go beyond this characterization. His example of the visit to the perfume factory, and the understanding of what “the piteous gestures and sad looks of signals in the rain” may suggest, allow that reading is also about experiential elements. Does this possibly indicate a turn to the mundanity of embodied practice? Or have these elements, perhaps, always been present in Eco as a part of his orientation to the pragmatism of Charles Sanders Peirce?

III. PEIRCE AND PRAGMATIC ELEMENTS OF SEMIOSIS

The phenomenological bent detectable in Eco’s latest writings is surely in accordance with the philosophy of Peirce—one of the main forces shaping Eco’s thought. Before moving on to discussing an act of reading in scientific practice, let me briefly touch upon the discussion of meaning in Peirce’s pragmatism.

Peirce was keen to point out that signs acquire their meaning in respect of the specificity of the situation in which they are enacted. According to Peirce’s pragmatism (or, as he later called it, “pragmaticism”), the meaning of a sign can be identified when possible actions that the affirmation or negation of such a sign would imply are specified. Peirce’s example of two people speaking about a house on fire further elaborates this point:

Two men meet on a country road. One says to the other, “that house is on fire.” “What house?” “Why, the house about a mile to my right.” Let this speech be taken down and shown to anybody in the neighboring village, and it will appear that the language by itself does not fix the house. But the person addressed sees where the speaker is standing, recognizes his right hand side (a word having a most singular mode of signification), estimates a mile (a length having no geometrical properties different from other lengths), and looking there, sees the house. It is not the language alone, with its mere associations of similarity, but the language taken in connection with the auditor’s own experiential associations of contiguity, which determines for him what house is meant. It is requisite then, in order to show what we are talking or writing about, to put the hearer’s or reader’s mind into real, active connection with the concatenation of experience or of fiction with which we are dealing, and, further, to draw his attention to, and identify, a certain number of particular points in such concatenation.35

The description of the conversation, not dissimilar to Wittgenstein’s philosophy of ordinary language and the situated action of Lucy Suchman, suggests that the meaning of the speaker’s words needs to be anchored in and dynamically updated with respect to the interlocutor’s immediate experience of the world.36 Thus an understanding of the utterance—“that house is on fire”—depends on the specific local positioning of the interlocutors in the situation of action.

This embedding of signs in the features of the world links Peirce’s semiotics to his pragmatism, which, furthermore, he associates with his being an experimentalist. As an experimentalist, Peirce explains that, in order to understand the meaning of an expression, one must conceive of the empirically observable phenomena that the understanding of such an expression implies:

Endeavoring, as a man of that type naturally would, to formulate what he so approved, he framed the theory that a conception, that is, the rational purport of a word or other expression, lies exclusively in its conceivable bearing upon the conduct of life; so that, since obviously nothing that might not result from experiment can have any direct bearing upon conduct, if one can define accurately all the conceivable experimental phenomena which the affirmation or denial of a concept could imply, one will have therein a complete definition of the concept, and there is absolutely nothing more in it. For this doctrine he invented the name pragmatism.37

According to the pragmatist position, meaning—“conception, that is, the rational purport of the word”—concerns the understanding of its effects upon possible actions in the world. This is to say that a sense of a sign cannot be divorced from its practically relevant effects: as a dynamic coordination of signs referencing one another, an act of semiosis can be brought to an end only when a habit is formed. A habit, while not exclusively a mental fact, can be defined by describing possible actions that it gives rise to.38 In other words, meaning can be specified by describing an enactment of the habit in a situation of action.

When Eco talks about contextual and circumstantial aspects of reading, he primarily works with the idea of encyclopedia bounded to textual borders.39 Yet his reliance on Peirce’s semiotics positions him in the midst of everyday embodied action. Considered in that light, his theorizing of reading does not appear disconnected from the intricacies of the practical endeavors with which readers, as embodied actors, engage.

IV. ENACTING THE MODEL READER: AN EXAMPLE FROM APPRENTICESHIP IN SCIENTIFIC PRACTICE

The aim of this section is to bring together the textual and the mundane, encompassing at once how readers shape the text that they engage with while the text shapes that involvement. To do so, I couple Eco’s discussion of reading with ethnomethodology—a social science approach grounded in phenomenology that is attentive to social reality as enacted by ordinary actors through their local, embodied activities.40 That discussions of reading in ethnomethodology may underplay the workings of text is not to imply a resistance to linking the two approaches.41

Here I attempt to explore a possibility of such linkages by discussing an example of reading where the readers together—through their embodied involvement with digital technology—participate in realizing the text they read. This involvement concerns a moment of scientific practice where, as part of an apprenticeship session, two researchers of cognitive neuroscience read a visual rendering of the human brain displayed on a computer screen. In attending to how the reading activity unfolds, we may discern a model reader distributed across the text to be read and the bodies involved in the reading practice. This model reader—textual and mundane at once—is, furthermore, anchored in and dynamically updated relative to the readers’ specific local positioning in the reading situation.

The example concerns the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technology. Together with its forerunner MRI, fMRI is a key modern digital imaging technology used for medical and scientific purposes. The goal of MRI is to provide detailed static renderings of the anatomic structure of internal body parts, such as the brain. This technique uses radio frequency, magnetic fields, and computers to create visual renderings based on the varying local environments of water molecules in the body. To obtain such visuals, a person (or, in fMRI practitioners’ jargon, an experimental subject or a subject) is scanned.42 During a brain MRI scanning session, hydrogen protons in brain tissues are magnetically induced to emit a signal that is detected by the computer. Such signals, represented as numerical data, are then converted into visuals of the brain as the brain anatomy of the experimental subject is imaged. The mapping of human brain function by use of fMRI represents a newer dimension in the acquisition of physiological and biochemical information with MRI. The technique is used to observe dynamic processes in the brain that are demonstrated by visualization of the local changes in magnetic field properties occurring as a result of changes in blood oxygenation. The role of fMRI visuals is, thus, to display the degree of activity in various areas of the brain: if the experimental data are obtained while a subject is engaged in a particular cognitive task, the visual can indicate which parts of the brain are most active during that task.

To show these results, however, fMRI visuals require extensive analysis in the laboratory. During analysis sessions, fMRI practitioners use computers to engage with their data, shaping the appearance of fMRI visuals. These practices are actions of reading. To catch the details of those readings, it is advantageous to observe apprenticeship and instruction sections as they render available what otherwise may go unnoticed.

Here we join an apprenticeship between a postdoctoral student, the old-timer in the laboratory, Octavia (O), and the newcomer, Nick (N), a first-year graduate student in neuroscience spending a semester in the laboratory. Octavia guides Nick through the data analysis session so that he can acquire the performative ability to eventually proceed on his own. The laboratory studies visual areas by applying the method of retinotopic mapping. As the general topography and location of the early visual areas relative to one another are believed to be, by and large, consistent across individuals, the researchers use retinotopic mapping to identify the configuration of the visual areas on the fMRI rendering of the subject’s cortex. Once the organization of the early visual areas is identified, that information is used to analyze data from the main experiment. If during the main experiment the researchers investigate how the early visual areas respond to the specific experimental task, they first need to map out the location and borders of these areas.

The idea behind the concept of retinotopy is that there is an orderly mapping between locations in each retinotopically organized brain area and the locations in the visual field. In other words, the retinotopically organized visual areas are considered to be point-to-point copies of the topography of the retina, where what is of interest are the topographic correspondences generated through a translation of information between the eye and the brain. Nearly all visual information reaches the cortex via the primary visual area (V1). V1 is located in the posterior occipital lobe within each hemisphere and provides a precise retinotopic mapping of the visual fields. In the left-hemisphere V1, the right half of the visual field is represented, covering 180° of the field circle. V1 projects in a topographically well-ordered fashion to V2 (second visual area), to then connect to numerous visual areas: V3, V3A, VP, V4, V5 or MT, V7, V8, and so forth. Once the projections of visual stimuli in V1 are established, the other retinotopically organized visual areas can be determined with respect to it since the successive areas are considered to be mirror images of each other.

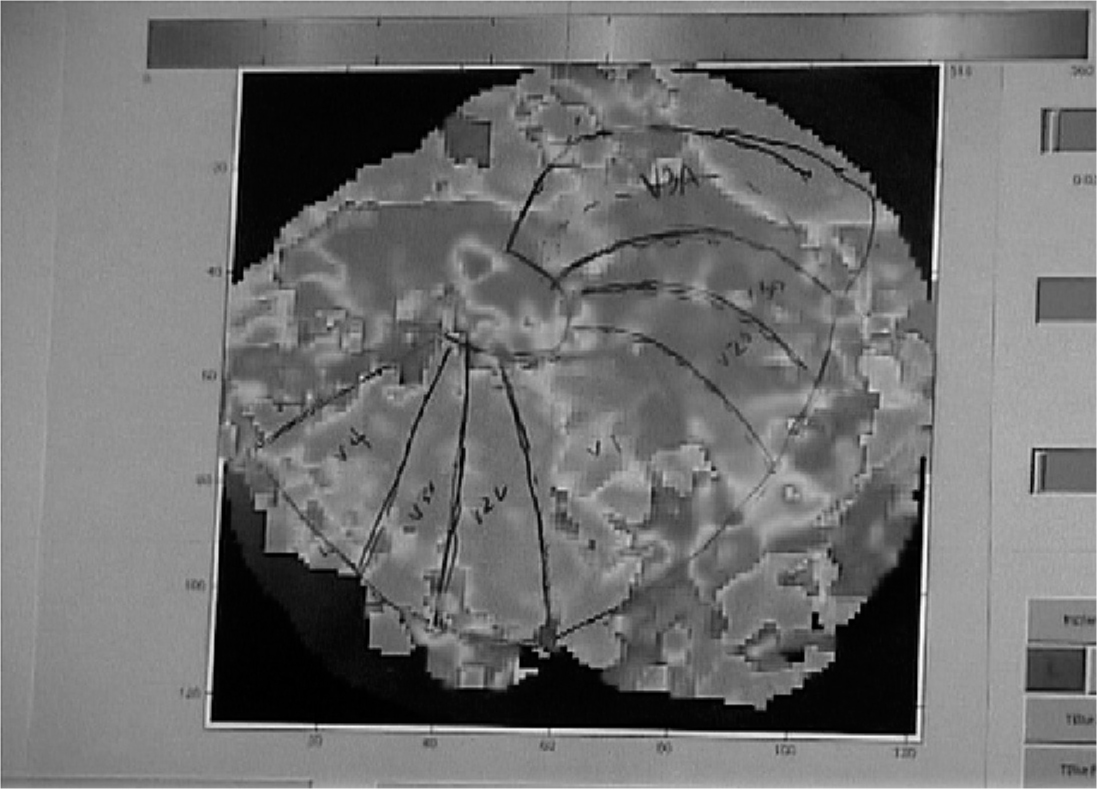

As a part of retinotopic mapping, Octavia and Nick are involved in identifying the organization of a phase map. The phase map is a static fMRI visual that shows the temporal relationship of the data to certain stimuli, where colors stand for the time at which neuronal activity occurred. When scientists want to obtain such a visual (or brain map), they present experimental subjects with dynamic visual stimuli intended to provoke waves of activation in their brains, such that variation in the temporal phase of the activation can be represented by changes of hue in a color map. Using the change in color, practitioners identify borders between visual areas on the human cortical rendering (as shown in Figure 1).

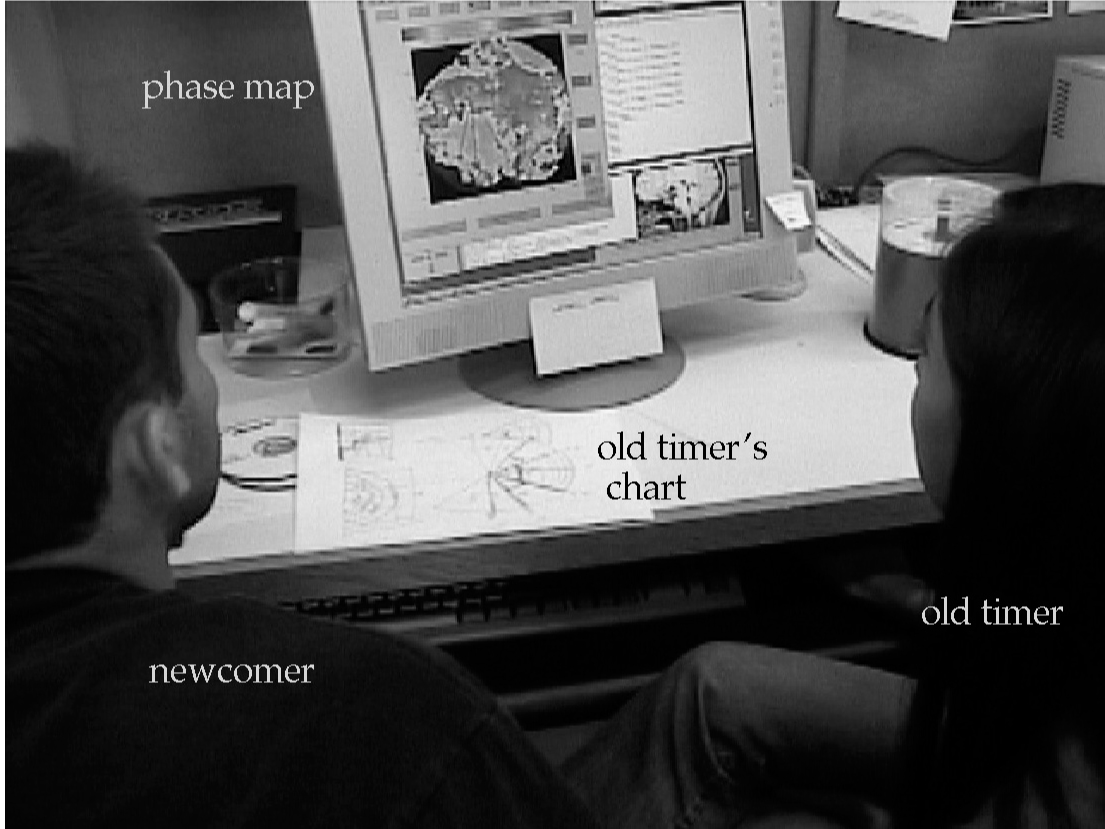

During the interaction reported in the following excerpt, Octavia and Nick are seated in front of a laboratory computer that displays phase maps, while I stand behind them with a video camera (Figure 2). The borders of the visual areas had already been traced (Figure 1) since the software that the laboratory members use allows practitioners to draw black lines directly on the fMRI visual. To identify these lines, the laboratory members use the color coding displayed on the screen. By understanding the response to the visual stimuli in terms of waves of activation that change in color over time, they employ the direction of the color change as an indication of the existence of the borders between visual areas.

Figure 1. Phase map with the traced borders of visual areas.

Figure 2. Nick and Octavia participating in the data analysis session.

Just before the reported interaction takes place, Nick expresses his uncertainty about the location of the borders indicated by Octavia. To explain further, Octavia first points to the horizontal array of colors situated above the brain scan (Figure 1) and designed to indicate the phase of the neuronal activity for voxels that are active as a response to experimental stimuli. Since the phase map may not reveal some of the colors, while the other colors may cover a very large portion of the map, she then takes advantage of the data’s digitality by “rotating the color map.” When practitioners talk about “the rotation of the color map,” they refer to a computational process that changes the correspondence between colors and the time of neuronal response so that, for example, a response phase that was represented in the original color map by red may become yellow in the rotated color map. Octavia exploits this feature of the software to find an alternative view of the data.

After she rotates the color map, Octavia attempts three consecutive times to recognize and point to the color change on the phase map so that her colleague can see the borders of the brain areas. The following excerpts from interaction report on these attempts:43

1 O: So now it’s going from //re::d (.) red to pink to blue (3.5)

2 N//re ::d

3 O: and maybe it goes out to red to pink again ((while pointing different colors on the map to briefly place her hand on the desk)) (0.1)

4 (and up there where it breaks down) ((points again onto the upper portion of the map to briefly place her hand on the desk)) (1.5)

5 ((Mumbles while going over the color scheme)) ((points back and forth between different colors on the map))

6 ((she raises her voice, and her speech becomes clearer when she pronounces the name of the second and subsequent visual areas)) V2 V3 (1.0) V4 ((puts her hand down)) (3.0)

7 So ok so so one theory is that hahaha ((silently laughs)) ok V1 (.) so pink to blue is V2 (2.0) ventral then blue to pink (1.0) is V3 ventral and then pink back to blue is V4 ((points different colors on the map))

8 ((puts her hand down, and turns toward the newcomer))

9 That’s my best guess based on the data

10 N: ((tries unsuccessfully to take the floor))

11O: Even though it’s very unclear

12N: So V1, V2v, V3, and V4 ((while pointing with the pencil on the map))

The excerpt shows Octavia using her hands to work on the computer and to gesture while she also pronounces the names of the colors as she matches their changes with the horizontal color array (located above the brain map). She starts by identifying the sequence of colors in line 1, placing her index finger on the map and pronouncing the word red with a prolonged “e” sound. The temporal organization of the action allows her to look at the horizontal color array and notice that, to identify the color sequence, the red should be followed by pink and blue colors. As Octavia pronounces the word red, Nick joins the enumeration of the colors by contemporarily uttering the word red (line 2); he shows that he can see what his colleague is indicating. However, Nick’s coparticipation in naming the colors ceases shortly thereafter; indicating to Octavia his difficulty in reading the configuration of the map.

After identifying the change from red to pink to blue, Octavia pauses for 3.5 seconds (line 1). While pausing she keeps her index finger, placed on the brain map, in the steady position. As she proceeds to indicate colors in the higher visual area (line 3), her finger is still on the map, while she prefaces her listing of the colors with “maybe.” At the same time, her talk becomes quieter and the moments of silence pervade the activity (lines 1, 3, 4).

Octavia’s second attempt to point out the change in colors starts in line 5. At this time her voice is so soft that she seems to be mumbling to herself, using speech as a self-regulatory process rather than talking to Nick. While mumbling, Octavia points back and forth between different colors on the map, continuing gesture and talk during the problem solving. In line 6, however, her mumbling turns into clear speech and her pointing becomes linear. As her semiotic conduct indicates that she finally sees the sequence of color that she knows needs to be identified, the practitioner starts to list the visual areas from V2 up: “V2 V3 (1.0) V4.” Thereafter, she takes her hand away from the computer to mark the momentary accomplishment of the task.

In line 7 Octavia resumes the action of listing colors on the map for the third time. By prefacing her pointing with the phrase “one theory is that,” followed by a sotto voce laugh, Octavia expresses the uncertain character of her quest to identify the areas on the brain map. After that, she turns toward the newcomer to check if he saw what she saw and what she had indicated to him (line 8). She then, once again, adds that the identification of the areas is still tentative. This can be seen in line 9, where Octavia explains, “That’s my best guess based on the data,” as she asserts again in line 11 “even though it’s very unclear.” Her remark “that’s my best guess based on the data” is followed by Nick’s demonstrations that he can start to read the structure of the data. After two unsuccessful attempts to take the floor (lines 7 and 10), Nick steps in and enumerates the areas on the map (line 12). He demonstrates that he sees what the old-timer claims exists on the map, as he is able to continue with the reading.44 At this point Nick appears to align with the model reader. This model reader is instantiated across the text, material resources, and the bodies involved in the reading practice.

First, the colors on the brain map are there to indicate the expected and culturally appropriate paths for reading. Just above the brain map that Octavia and Nick are looking at, there is the horizontal array of colors (Figure 1). The array guides the readers as it asks them to identify the same sequence of colors on the brain map. The colors inscribed in the map indicate the phase of the neuronal activity for voxels that are active as a response to experimental stimuli. As such, they should not be read as mimicking what they stand for (these colors are not what you would see if you were able to open a skull and look at the brain of a person involved in a visual task). By implying that there is an orderly temporal relationship between the fMRI data and the dynamic visual stimuli presented to the person who was scanned, the colors are instead a way to represent the changes in neuronal processes through time. These spatial renderings contain the knowledge about the organization and functioning of human visual cortex: they imply that the visual field is topographically organized and ordered in a series of successive areas arranged as mirror images of each other. These ideas are aspects of the model reader that Octavia and Nick try to align with. In this sense the colors inscribed in the fMRI visual and in the horizontal array not only allow the practitioners to engage in a certain way with what is on the computer screen but are also theory laden.

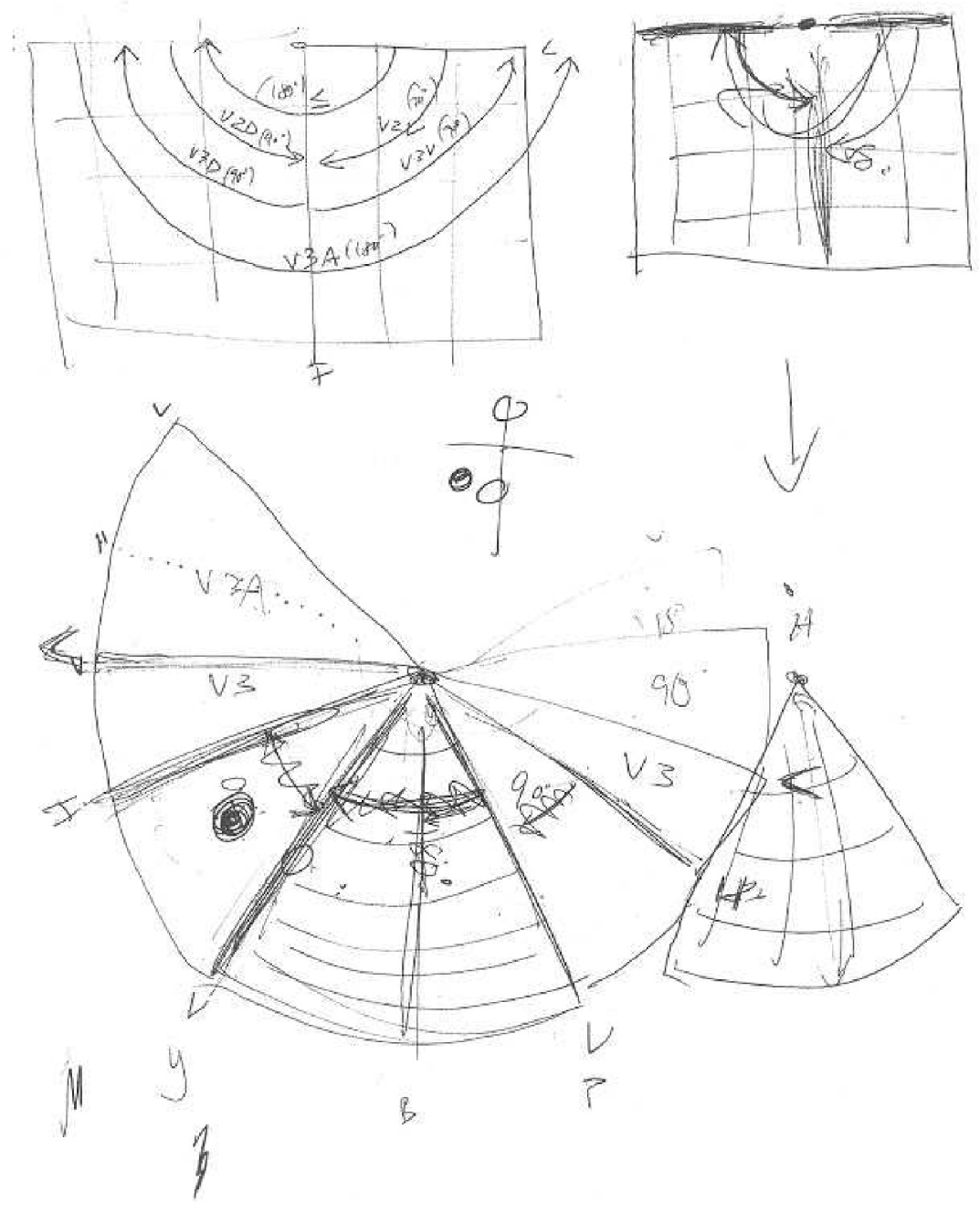

The aspects of the model reader can also be found in a variety of material objects in the laboratory. For example, in the practice of retinotopy, practitioners may use charts that exemplify the normative way of identifying the structure on the map. In fact prior to the interaction featured in the excerpt reported above, Octavia and Nick worked with such a chart (Figure 3). To analyze the digital visual, they first drew a chart on a piece of paper. Whereas on the brain map some areas look much larger than others as their shape frequently appears significantly distorted, on the chart the areas are represented as the same or similar in size. When the chart is adjoined to the map (as seen in Figure 4) its function is to allow practitioners to find an expected order in the messiness of the fMRI visual.

In addition to these textual-material elements, for Nick the model reader also involves Octavia. As Octavia’s multimodal actions guide Nick in accomplishing certain acts of meaning-making, they function as aspects of the model reader. It is not only colors and charts that inscribe expected readings, but also the signs performed through embodied interaction. These signs are publicly available as Octavia’s multimodal handling of the computer and orienting to her interlocutor are coordinated with the textual architecture in that specific situation of apprenticeship. Thus we can say that the text organizes its expected readings by coopting Octavia in its workings.

Figure 3. The chart of the visual areas.

Gesturing and digitally “altering” the brain visual is a relevant step in allowing Octavia to gradually assemble a support for the proposed layout of the visual areas. To transform the not-yet-legible data into workable evidence, she coordinates the prosody and rhythm of her speech with her pointing toward and touching of the phase map as she changes the colors of the map. While Octavia enumerates the colors and keeps her pointing hands touching the screen, she takes advantage of the digitality that characterizes fMRI data.45 Reading the data, as she manipulates their visual features, involves clicking on the computer mouse, using keyboards to type commands, and gesturing over the screen. While gesturing and organizing the stream of her speech in coordination with the semiotic actions of her interlocutor, Octavia is also able, for example, to change the view of the data, adjust colors, and inscribe lines that stand for borders between visual brain areas.

Figure 4. The chart adjoined to the brain map on the computer screen.

As Octavia—who previously participated in numerous data analysis sessions—works with this data set, she can use as resources the laboratory knowledge and the knowledge of the larger neuroscience community, articulating them as paths for reading the brain map. To provide indices that guide Nick’s inferences, Octavia makes the shared knowledge of the community available to her colleague, encouraging and regulating his interpretations. Even when in lines 10, 12, and 13 she displays difficulties in identifying the borders between the brain areas, her effort parallels the larger trend in the field of brain mapping, where the existence and position of higher visual areas are regarded as more controversial than is the case for the earlier visual areas (whose borders are considered to be an accepted scientific fact).

However, Octavia’s involvement not only concerns cultural knowledge and reference to other texts (past and future) but is also about situated coordination in the moment of apprenticeship. The model reader—not entirely constituted by the text—is also constantly reformulated in the proceeding of the interaction. For example, as we follow Octavia and Nick, we are made aware of the complexities that characterize the production of intelligibility. This concerns not only the newcomer but the old-timer as well. As Octavia analyzes the data, the activity is filled with hesitations, prolongation of actions, and brief suspensions. In her effort to indicate how the brain visual should be read, her actions are tentative, hypothetical, and creative, or what Peirce calls “abductive.” In his discussion of pragmaticism, Peirce writes: “Its only justification is that from its suggestion deduction can draw a prediction which can be tested by induction, and that, if we are ever to learn anything or to understand phenomena at all, it must be by abduction that this is to be brought about.” Furthermore:

However man may have acquired his faculty of divining the ways of Nature, it has certainly not been by a self-controlled and critical logic. Even now he cannot give any exact reason for his best guesses. It appears to me that the clearest statement we can make of the logical situation—the freest from all questionable admixture—is to say that man has a certain Insight, not strong enough to be oftener right than wrong, but strong enough not to be overwhelmingly more often wrong than right, into the Thirdnesses, the general elements, of Nature. An Insight, I call it, because it is to be referred to the same general class of operations to which Perceptive Judgments belong.46

As seen above, Octavia cannot simply apply an already attained knowledge of how the brain rendering should be read to make the brain map visible. While she uses her pointing hands to indicate the existence of the borders on the brain map, she organizes her own seeing. In fact, when in line 9 Octavia talks about her “best guess,” she indicates her awareness that, despite the structure existing in fMRI visuals, reading brain scans is a complex and somewhat tentative process. This tentativeness is occasionally settled as Octavia practically engages the world. When Octavia uses her pointing hands to indicate the existence of the borders on the brain map, she organizes her own seeing. She also takes advantage of the digital quality of the data that allows her to change the view, adjust colors, and inscribe graphical features over the brain image, so that she can detect the paths for reading the text. In this sense, while Octavia enacts the knowledge of the community, she also further shapes that knowledge, relying on hypothetical thinking and creativity anchored in the practicality of the moment.

So what we end up with here is a model reader that is distributed not only across the text to be read with the artifacts and equipment in the laboratory, but also across the bodies of those involved. As she aligns with the knowledges of the laboratory and the larger scientific community, the experienced scientist anticipates, directs, and even demands specific interpretations of the imaging data. In this sense, her actions participate in how the text regulates its readings, and how it exercises control over its interpretations, as it provides indices for its expected readings. But this model reader is also constantly enacted and reenacted in interaction. Once the collision of the empirical and model reader is taken into account, the model reader appears not as a firm structure but as a phenomenon that, as the reading of a text proceeds, unfolds as a multiparty act in the specific environment of practice. Eco’s discussion of reading provides critical resources for dealing with this interplay. The challenge is to see how a complex set of positions may be fine-tuned as we describe the subtleties of the material and embodied features of actual reading practices.

MORANA ALAČ

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO

OCTOBER 2015

NOTES

1. Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979); Lector in fabula: La cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi (Milan: Bompiani, 1979); The Limits of Interpretation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990).

2. Umberto Eco, Kant and the Platypus: Essays on Language and Cognition, trans. Alastair McEwen (New York and San Diego: Harcourt Brace & Co., 2000); Eco, On Literature, trans. Martin McLaughlin (Orlando: Harcourt, 2004).

3. Eco, The Role of the Reader.

4. Eco, Lector in fabula (my translation).

5. See Eco, The Role of the Reader, 3–4.

6. John D. Bransford and Marcia K. Johnson, “Contextual Prerequisites for Understanding: Some Investigations of Comprehension and Recall,” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 11 (1972): 717–26.

7. Ibid., 721.

8. Ibid., 717.

9. Ibid., 725.

10. Julia Kristeva, Le Texte du roman (The Hague: Mouton, 1970). Roland Barthes, S/Z (Paris: Seuil, 1970); Barthes, Le Plaisir du texte (Paris: Seuil, 1973). Algirdas Greimas, Maupassant—La Sémiotique du texte: exercises pratiques (Paris: Seuil, 1976). Janos Petöfi, Vers une théorie partielle du texte (Hamburg: Helmut Buske, 1975).

11. Eric Livingston, An Anthropology of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

12. Eco, Lector in fabula, 8.

13. Ibid., 17.

14. See Eco, The Limits of Interpretation.

15. See Barthes, Le Plaisir du texte.

16. Eco, Lector in fabula, 5.

17. Ibid., 11.

18. Roland Barthes, “Rhétorique de l’image,” Communications 4: 40–51. Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976). Ugo Volli, “Some Possible Developments of the Concepts of Iconism,” VS 3: 14–29.

19. Eco, Kant and the Platypus, 342.

20. To deal with “primary iconicity,” or the iconic character of perception, Eco follows Gibson’s idea of conformity: “the judgment of likeness between stimuli reflects a concordance between the perceptual system and the invariants of the informative stimulus.” James Gibson, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1996), 105.

21. Eco, Kant and the Platypus, 352.

22. Ibid., 353.

23. In his semiotics of the text, Eco has explicitly engaged the problem of reading literary and artistic texts. Yet his theorizing has a larger scope. For example, in Limits of Interpretation, he points out that literary texts magnify the role of the reader in generating the meaning of the text, but this is not to say that other texts function differently: “It must be . . . stressed that such an addressee oriented approach concerns not only literary and artistic texts but also every sort of semiotic phenomenon, including everyday linguistic utterances, visual signals, and so on.” Eco, The Limits of Interpretation, 45.

24. Eco, On Literature, 179–80.

25. Ibid., 184.

26. Ibid., 188–97.

27. Ibid., 184, 198–99.

28. Ibid., 199.

29. Ibid., 195.

30. See ibid.

31. Ibid., 200.

32. Eco, The Role of the Reader, 176.

33. Eco, Lector in fabula, 24.

34. Eco, The Limits of Interpretation, 48–50.

35. Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers, ed. A. Burks, C. Hartshorne, and P. Weiss, 8 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931–1958), 3.419.

36. Lucy Suchman, Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1954).

37. Peirce, Collected Papers, 5.412.

38. Ibid., 5.491.

39. For example, Eco, The Role of the Reader, 19.

40. See Harold Garfinkel, Studies in Ethnomethodology (Englewood Cliffs: Polity Press, 1967/1984); Garfinkel, Ethnomethodology’s Program (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002); Harold Garfinkel, Michael Lynch, and Eric Livingston, “The Work of a Discovering Science Construed with Materials from the Optically Discovered Pulsar,” Philosophy and the Sociology of Science 11 (2002): 131–58; Alfred Gurwitch, The Field of Consciousness (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1964); and Alfred Schutz, The Phenomenology of the Social World (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1967).

41. See Eric Livingston, An Anthropology of Reading (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

42. See Morana Alač, Handling Digital Brains: A Laboratory Study of Multimodal Semiotic Interaction in the Age of Computers (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011). My intention is to use the term “visuals” rather than “images” to avoid some of the connotations implied in the word “image.”

43. To render the intricate ways in which interlocutors coordinate with each other, the transcription adopts the following conventions according to the tradition of conversation analysis, as indicated in Emanuel Harvey Sacks, A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson, “A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation,” Language 50 (1974): 696–735, and Gail Jefferson, “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction,” in G. H. Lerner, ed., Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation (New York: John Benjamins, 2004), 13–31.

(0.0) Numbers in brackets indicate elapsed time in tenths of seconds.

(.) A dot in parentheses indicates a brief interval within or between utterances.

( ) Parentheses indicate that the transcriber is not sure about the words contained therein.

(( )) Double parentheses contain the transcriber’s descriptions.

// The double oblique indicates the point at which a current speaker’s words are overlapped by another’s words.

: The colon indicates that the prior syllable is prolonged.

44. See Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations.

45. Michael Lynch, “Laboratory Space and the Technological Complex: An Investigation of Topic Contextures,” Science in Context 4, no. 1 (1991): 81–109.

46. Peirce, Collected Papers, 5.173. For a discussion of Peirce’s abduction and semiotics, see Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, 131–33.