This is a one-man play. A brief description of the main characters portrayed is given here.

Sunil(34, as narrator)The narrator of the play, he is a thoughtful and compassionate character who is presiding over the closure of his father’s convenience store. After being approached by a journalist he shares the stories of the three men who most influenced his life.

Areendum(38)Sunil’s great, great grandfather who worked on the sugarcane plantations in the 1870s. A dignified and resilient character, his dream was to own a convenience store which he believed would empower his family and community.

Manoj(58)Sunil’s father, a highly-regarded shop owner who becomes a victim of violent crime. He is a close friend to Johnny and many people in the community consider him to be representative of Reoca’s heartbeat.

Johnny(64)A mentor to Sunil, he is a retired teacher and runs the local butcher shop. Widely regarded as an inspiring community leader, he finds himself in an unexpected battle when his little-known romantic side is revealed.

Themba(37)A multi-skilled and philosophical labourer who becomes a victim of racism and injustice in Reoca. His friendship with a young Sunil leads to him educating the boy about cricket and Zulu culture.

The old sugarcane plantations in Natal and the town of Reoca, an Indian suburb in Durban.

Reoca Light extends over a variety of time periods in its two main settings – the sugarcane plantations of Natal (1870s) and the fictional town of Reoca (1980s; 1990s; early millennium; current day). It focuses on a particular Indian family and their neighbours but deals with the socio-political issues which impact on the whole of the Indian South African community as well as, to a lesser extent, the Zulu community in Durban.

The different stories shared by the chief protagonist examine issues peculiar to Reoca as well as the impact of the broader factors shaping South Africa’s socio-political landscape over three decades. Racial prejudice, ethnic rivalry, generational conflict and erosion of society through violent crime are all explored as the little town struggles with massive change.

Whilst the fictitious town may be seen in some quarters as representative of the neighbouring districts of Avoca, Redhill and Effingham Heights, the author did not want to choose a real place because he believes that the many stories in the play occur regularly in any number of so-called Indian townships. Therefore he felt he should not choose one specific, real place.

The title Reoca Light has a double meaning. Firstly, it refers to the Mohan’s convenience store, which was the place for community gatherings and therefore became known as the “light of Reoca”. Secondly, it refers to the spiritual response the chief protagonist receives from the universe when he undertakes certain actions in Reoca.

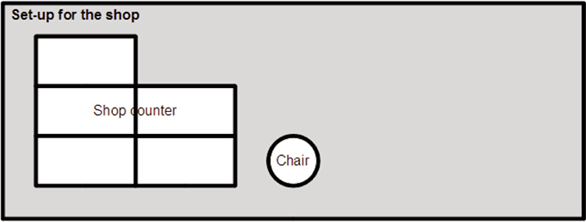

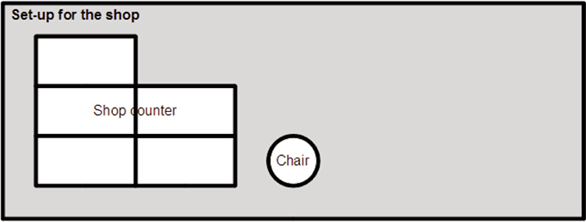

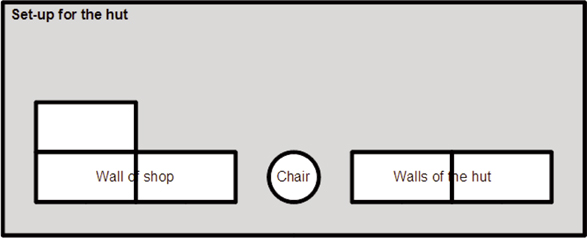

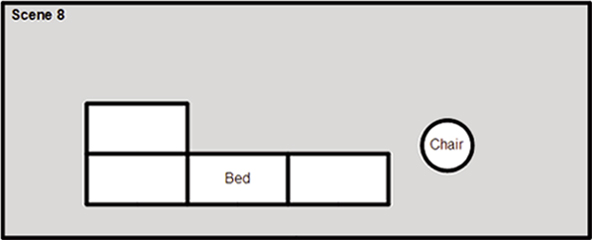

The bulk of the play takes place in a designated portion of a small convenience store and the little hut behind the store. These settings are represented by a number of black boxes/ottomans ranging in size between 40 and 80 cm in length. The actor switches between the store and the hut as he portrays the various characters. However, the first and last scene of the play take place on a typical sugarcane plantation in the 1870s. In the first scene, the shop counter and any other contents of the shop should not have been set up as yet because the actor must occupy the same space which becomes the shop in the latter scenes. The boxes/ottomans are brought on after the first scene.

This is merely a basic sketch of the layout. No flatage is depicted.

Special comes up on Areendum Mohan Rastogi, who is on centre stage, on the cane fields of Natal at about the 1870s.

The sun is setting Biswas. Just a little while longer now. You’ll get through, don’t worry. Then you can rest well tonight. And tomorrow you’ll feel better. You must eat with us tonight. Pallavi is making pea dhal. Hmm. I love pea dhal. (He looks around.) No, don’t worry. He’s not looking this side now. We can talk. You know, earlier today I spoke to Mr. Worthington again. Why you looking at me like that? I told you he’s not a bad man… he’s okay. I told him what I want to do, you know. In a few years, maybe. To start a little shop. For basic things, you know. He said he thinks, I might do that well. And he’s very happy with the housework Pallavi is doing for him. So he said, maybe he can help us. And maybe… maybe in the future we can run a shop on his property. (Pause) I know you think I’m just dreaming. But I tell you, he was serious. We have to try these things, Biswas. To try to make a better life for us. To help our people. I feel, this is my Dharma. (Pause) We can’t go back to India now, Biswas. This is our home.

Lights fade to blackout.

Musical interlude – classical Indian music.

The shop counter is set up.

Lights come up on the main character, Sunil, who is on centre stage, inside his father’s shop. He is in conversation with a local reporter, Mr. Rajpaul.

You know, Mr. Rajpaul, we never thought that the Sewlal brothers would sell their shops and move out of Reoca. Ajith and Sujith, the butcher and the baker. Hmm, I remember as a little boy being lured by the scent of chocolate lamingtons, and my dad buying our favourite running fowl on Saturday mornings. (Pause) The Sewlals were the ones who had allowed my Ma to set up her little Wendy Hut behind the shop building – the Murkoo Aunty they called her – she sold crispy murkoos, hot samoosas, tangy puri pathas – hmm, so many delights. And they called my father Sweet Uncle. Every Friday and Saturday afternoon he would load his basket with my mother’s treats and try to sell them around the Reoca district. And he would give each child a little sweet, whether his parents bought anything or not. Ja, that’s where it all began – behind the Sewlal brothers’ bakery and butchery. You tell your readers that, Mr. Rajpaul. Before Mohan’s Superette, there was the Hot Hut, with the Murkoo Aunty and the Sweet Uncle. (Pause. Sunil packs a few items.)

You know, my dad was really surprised at how low the brothers sold their premises to him and Uncle Johnny. Uncle Johnny took over Ajith’s butchery and my dad turned Sujith’s bakery into a convenience store. And my mum brought her treats from the back to the front. I tell you, Mr. Rajpaul, the Reoca people just took to the new shop. It became their special meeting place. What’s that? Ja, almost immediately, Mr. Rajpaul. You know, there were so many people who became part of the shop. We set up some lovely tables outside… and people used to spend hours, just talking. We even had our own shop boys.

(Music to introduce shop boys and then illustration of their mannerisms.) ‘Hey, show me all your cards… you colour cutting. Four ball! Ja, came way my bra. Let’s dallah. (Pause) Hey, check that cherry. Wow! She’s hotter than my mother’s chicken curry on the open fire.’

Ja, there was a place for everyone at Mohan’s Superette and Johnny’s Butchery. As Uncle Johnny said to my dad:

‘Look at all of them Manoj. They seem so happy when they’re here. Sometimes, I wish they would stop having their meetings and buy some more mutton from me. I’m sure you sometimes think – if only some of them stopped talking about how well I arrange the store and bought some of the groceries in it. But it’s okay. Where else can they go? This is the light of Reoca. They come here to eat air.’ (Long pause.)

But it’s over now. It’s over Mr. Rajpaul. I don’t care how many more stories you tell me about how the people of Reoca want my father to keep the store open. I don’t care anymore. This last attack was the final straw. I mean, the man can barely move. It’s been two weeks and he hasn’t said a word. (Pause) I mean, we battled through the recession. We even found a way to keep the shop afloat when my mother’s medical bills became astronomical. But who would go on after four robberies in two years? And three beatings? You say our townsfolk want us to keep the shop open, but they did nothing to stop the attacks on my father. (Pause) No, what am I saying? What could they do? Those bastards had AK47s.

Three attacks and still the police have made no progress. I mean, we know it’s the same robbers. (Pause) You know, after the second attack, when Uncle Johnny decided to close the butcher shop, my father was still adamant.

‘No, I’m not closing. I won’t give in to those animals. I understand that Johnny has to close. They beat him up badly. I mean, he’s an old man now. And he hasn’t got family support. But we must carry on Sunil. The police will catch these guys. They’ll never come here another time.’

But now his spirit is crushed. You know, Mr. Rajpaul when I saw him at the hospital last night, I looked into his eyes. And I knew what he wanted to say.

‘You remember when I told you Sunil, about how my father had told me about your great, great grandfather, Areendum Mohan Rastogi. And how he used to dream when cutting cane of owning a little shop one day. We were living his dream. Why did it have to end like this?’ (Long pause.)

Alright, that’s it, Mr. Rajpaul. I have nothing more to say. Please leave. You have enough for your article. Please. (He motions for Rajpaul to go.) And please don’t turn this into a gossip column. Like you sometimes do with your articles. (Pause. Sunil packs some items for a few seconds. He stops then rushes out.)

Mr. Rajpaul. Mr. Rajpaul. Sorry for my rudeness. I’m just… tired. If you have anymore questions, you know, anything more specific… well, I’ll be here in the shop tomorrow morning. One last time.

Lights fade to blackout.

Lights come up as Sunil enters the store. He tramples on an envelope.

What’s this?

(He picks up the envelope, opens it and reads the contents aloud.) ‘Hi Sunil. Sorry I couldn’t wait for you this morning. Another urgent assignment just came up. There is something I would really like to know. Don’t worry – I’m not looking for gossip. I just want a sense of history…’ (Sunil stops reading.)

Well, Mr. Rajpaul, that’s good to know. (He continues reading.) ‘Your friend Selvin told me that you’d written a few stories about things that happened behind your shop. And in your little hut. About your former employee, Themba Dlamini, and Uncle Johnny and others. But you haven’t released these stories. Selvin said few people knew of these incidents…’ (He stops reading.)

That’s true. And those who do, remember them differently. (He continues reading.)

‘Please share some of these stories with us. For example – is it true that your dad and Uncle Johnny hid the political activist, Zaakir Ally, in your hut in 1988?’ (He finishes reading.)

Well, well, Mr. Rajpaul. How did you dig that up? I didn’t tell Selvin that. (Pause, as Sunil contemplates.) Yes, we hid Mr. Ally in our hot hut.

It was the early days of my adolescence. (Excert of relevant 80s music.)

My dad and Uncle Johnny had just taken over the shop. But we kept our little hut, exactly where it had always been. As a reminder of where it had all begun. And also to keep some extra stock. (Pause) I had only just begun to discover some of the horrors of Apartheid. And then on that one weekend, the big bad world came to Reoca. Uncle Johnny’s friend, Bobby Nair, had asked him to hide Zaakir for the weekend, as the liberation movement decided where to deploy him next. I mean, who would think to find him in little Reoca? But the police were hot on his trail. They raided our houses. So my dad and Uncle Johnny snuck Zaakir into the hot hut. I was curious. I had to see him. So I snuck over there on Saturday evening. Mr. Ally. It’s Sunil. I’m, er, Manoj, Mohan’s son. Are you, er, comfortable in there?

‘Come inside, my boy. Close the door. Quietly. Oh dear, I should be quiet myself. Be careful of your booming voice, Zaakir. I’m glad you came. I need some company. Oh, you find my accent strange… well, that’s because I was forced to spend most of my life outside my country… England, Ireland, Switzerland. (Pause) So, you’re Manoj’s son, hey? (Pause) Tell me, do you know how to play chess? Never mind. I’ll teach you. Come. Sit down.’

And so the great activist taught me how to play chess. And when we finished the game, he said to me:

‘One day you’ll play chess with a grandmaster. And you won’t play cricket behind your shop. Unless you want to. You’ll be playing cricket at the Wanderers, if you really want it. We’ll make that world for you. (Pause) But don’t ever forget the chess game you once played here in this little hut. Because this is the most complete place you’ll ever experience.’

And then we heard the savage banging. And I heard the cops shout: ‘We know you’re in there Ally. We’re coming to get you!’

I don’t know to this day who had ratted him out. But I can still remember how he leaped out of that little window. And then bolted away like that magnificent springbok I had seen on TV. And the cheetahs sprinted after him. Mercilessly hunting their prey. But they didn’t catch him that day. They never did. (Pause) He helped to create our new world. And then became another forgotten hero of the struggle. (Pause) Yes, Mr. Rajpaul, Zaakir Ally once hid in our hut, for a while. (Pause) And there were others who hid there too. At various times. Themba, Uncle Johnny, even my dad. (Pause) I’m not sure your article can capture these moments, Mr. Rajpaul. I know you’re looking for an angle. Everybody knows what happened from week-to-week inside and in front of our shop. But not behind it. (Pause) Ag, maybe… maybe it’s time I revealed these stories. Okay, Mr. Rajpaul. I’ll tell you some of the things that happened at the back. About the three men who most influenced my life. The story behind the store.

Lights fade to blackout.

Lights come up on Sunil on centre stage. He is holding a cricket bat and ball, which he occasionally uses during this scene. Snippet of the National Anthem plays.

It was the beginning of our new world. The world my dad and Uncle Johnny had longed for. The world Zaakir Ally had promised me. It was then, in my first senior year at high school, that I came to know Themba Dlamini. The man who taught me the on-drive.

Before Themba came to work for us, he used to work as a gardener and all-round handyman for the Singh family. The Singh’s were the rich family on our street. They lived in an elegant double-storey house, on a little hill overlooking our shop. There was Pappa Singh:

‘People, my friends, we have to stop the deterioration of our town. Together. How can we let it become so filthy, so uncared for? Our grandparents must be turning in their graves. This is our home. Let’s make it beautiful again.’

Pappa Singh always spoke like he had a giant carrot up his arse. Nobody liked him. When he ran for local councillor, he only got six votes. He was one of those who called the ANC terrorists in the old South Africa, but in the new South Africa, he told everyone they were a great party. (Pause)

Then there was Mamma Singh:

‘Hello ladies. Reena, stop staring at my panjabi like that. You’re embarrassing me. Yes, yes ladies. I got it on my last trip to Dubai.’

Mamma Singh didn’t say much. She just glided from boutique to hairdressing salon. And occasionally our shop. (Illustrate) People thought she was gorgeous, especially when she batted those eyelids. But I didn’t like what I saw in those eyes.

And then there was their only child, Manesh. Golden, they called him. He was a snotty-nosed little shit.

‘My father is an engineer. Your father is just a shopkeeper. You’ll only got one shop. We own three factories. But never mind. You can still play cricket with me.’

Mamma and Pappa Singh sent their Golden child to every extracurricular activity they could find. Piano lessons, karate school, drama classes. (Illustrate) But he was useless at everything. Except cricket. He could bowl fast. And make me jump around. When we played behind the shop. (Illustrate the extravagant actions of both boys.) And his father would peer over their fence sometimes, egging Golden on.

‘That’s right son. Push him back. And then pitch one up. Yes, bowled him! No, no Golden. Don’t give him such a nasty sendoff. Be a gentleman. The boy is trying.’

Now the Singhs also had two dogs – Bruno and Deeno. Bruno was a hotshot – the district’s top dog. He was devoted to the Singhs and ferocious to strangers. (Illustrate Bruno’s actions.) When he jogged down the street, the district’s dogs sprinted into their kennels. They showed no such fear for Deeno. Deeno the dunce, we called him. He was fat and lazy. Little puppies used to creep up on him, scratch him and then dare him to chase them. But he never moved. He didn’t give a shit about the Singhs. But he loved Themba. He always managed a little wag of his tail when he was around him.

‘Deeno, tomorrow we will walk to the station. My cousin is coming to stay with me for three days. He is going to cut Mr. Pillay’s grass. And Mrs. Govender’s. Hey Deeno – you’re looking bad. I think we must leave very early if we’re going to make it to the station on time. Don’t worry my boy. Your day will come too.’ Themba seldom spoke. But there was much wisdom when he did. And he worked tirelessly. Everyone was so envious that the snobbish Singhs had such an outstanding gardener. But then one day it all suddenly ended. After a big family function, some of the Singh’s jewellery went missing. Pappa Singh was pissed off. But who could he blame? He didn’t have the balls to accuse his relatives. So he did the thing that many people in our district did – he blamed the maid and the gardener. Conspiracy, he said it was. And fired them both. I found Themba sitting in our hut later that evening.

‘Aw, sorry Sunil. Please don’t tell your father. Er, Mr. Singh, he chased me away. You know, he fired me. And he say I can’t stay in his outbuilding anymore. So I don’t have anywhere to go now. I just want to wait here for a short while.’

He ended up staying for a long time. My dad and Uncle Johnny hired him as their all-round assistant. And let him make the hut his home.

And so I came to spend every Friday afternoon and evening with Themba. You see Themba loved cricket. And he had gained much knowledge about the game over the years – through talking to people, listening to commentary, watching games on his portable TV. And now he was my cricket mentor.

‘Aw, aw, come on now Sunil. You are not moving your feet. Is there glue on the crease? Because you are stuck there. Come on. Come on. He’s bowling slow spin. Dance down the wicket. Hey, I’m going to have to teach you to dance like a black man. Then you’ll skip down the wicket.’

Themba, the man of few words, certainly had a lot to say about cricket. But I listened to him. He was a smart coach. And though we were just playing behind our shop, it seemed like there was some magic there now.

Hey, come on bowl, Selvin. (Sunil puts on an Aussie accent.)Right, Selvin Moodley it is. In he comes. It’s short. Mohan smacks it for six. Oh look at that. It’s over the Singh’s fence. (He drops the accent as he realises where the ball has gone.) Oh shit. Hey Manesh, pass the ball. I know you’re there. Come on, pass it Manesh. Where the hell are you throwing it? Look at that idiot. Hey Deeno, stop the ball. Oh, come on. It’s gone into the drain. Hey Deeno. The ball was just in front of you and you couldn’t stop it. What a lump. (Pause) Yes, Deeno seemed to have moved from the Singhs with Themba. But that’s all the moving he did.

Every Friday afternoon – cricket with the coach. And every Friday evening – traditional dinner with the Zulu chef. The hut where I had savoured my mother’s murkoos, was now filled with the delicious smells of sausage and pap. And after supper Themba would tell me stories of his village.

‘Hey Sunil, every Friday night in our village, everyone will come together on the hill. And each one will bring the bit of food he can afford. To share with the people. And the Chief will bring the beer. He will make a speech but no one will listen. They are waiting for the young men to beat the drum, and the young ladies to dance. And then everyone will join in, even my gogo. Dance till Saturday morning. (Pause) You know, you used to have something like that in Reoca. I don’t know why it stopped.’

That whole year, I couldn’t wait for Fridays. (He plays a few cricket shots and we hear sounds of crowds cheering.)

Then one day our special gift from my aunt in India – a good luck token which was an ornamental crystal prism, went missing from the shop.

‘I can’t believe it. Who would take our crystal ornament? And why? How did they sneak into the back office? (He thinks for a moment.) Oh no, wait. I left the door open for a few minutes when I was talking to Mrs Singh. But who could sneak in… what Sharmilla? (Pause. Then he lowers his voice.) No, no, don’t gesture towards Themba. He didn’t do it. Come on Sharmilla. Themba’s been with us for over a year. There’s nobody more honest than him.’

Sunil is spinning his cricket ball as he talks to Themba.

I know what you’re thinking Themba. My employers don’t accuse me of stealing their precious ornament, but deep down they think I might have done it. And you’re angry because it’s the birth of the new South Africa, but these Indians think black men are thieves. But honestly, nobody thinks you stole it Themba. We all believe in you.

‘I wasn’t thinking what you are saying Sunil. I was thinking, the shop is going well now. It’s not needing me too much. And Bongani is here now. (Pause) Plus, you are good in cricket now – aw, school captain. I mean, you are not as good as that Ishaan boy from over the other side of Reoca, but hey that one no one can beat. You are very good. You don’t need me no more. (Pause) You know, my sister told me our ma is sick, so I think I must go help her take care of her.’

I’m sorry about your ma, Themba. But you can visit her for a while and come back. To help me prepare for the inter-school championship. (He holds his head.) Ouch! It’s that idiot Manesh – he hit another one of his balls here! You know, since his father stopped him from playing here, he deliberately hits those balls here. No, it’s true Themba. He wants me to go fetch for him. He’s a sick shit. Hey Manesh, I’m not chasing after your ball. It’s rolling down the road. (He hides the ball behind his back. Then looks at it carefully.) Hey, it’s the new Allan Donald ball. With the markings to help you with the different grips. Lucky shit. Hey, I’m going to teach him a lesson. I’m going to keep this ball. Don’t look at me like that Themba. He doesn’t deserve it. (He contemplates.) Er, look, I’ll just keep it for a while. Then I’ll give it back. Hey Manesh, your ball is gone into the drain. Sorry mate. (Pause)

I can still remember that look on Themba’s face – don’t do it Sunil. You are not a thief. You don’t need the rich boy’s toys.

But I ignored him. And I occasionally played with my new toy. Who could catch me? Manesh wasn’t allowed to play with me anymore. His father seldom walked this way. And his mother wouldn’t know it was his ball. (Pause) I didn’t reckon with Bruno the dog. He knew his master’s toy. So one day he began barking ferociously at me. As fate would have it, Pappa Singh and Golden were walking the beast on a different route that day. Bruno raced at me, dropped me on my back and grabbed the ball.

‘What are you doing boy? What’s that? (He examines the ball.) Hey, this is my ball. My Allan Donald ball! You stole it! Thief!’

No, I didn’t steal it. It’s mine. I’ve had it for months.

‘Look here. M.S. My initials.’

‘Well, well. Like coach, like pupil. What’s the matter boy? You couldn’t wait for your father to buy the ball for Christmas? You had to have it now. And you dare to exhibit it. You couldn’t even play with it secretly. You arrogant swine!’

I found it lying next to the drain. Manesh must have hit it over. I didn’t know it was his. I didn’t steal it. (Pause)

And then I noticed that my father had come to the back. I could see he didn’t believe me. He looked ashamed. (Pause)

I’m sorry. I just wanted to use it for a while.

‘Well, what are you going to do, Mr. Mohan? Your son is a common thief! You know I should press charges. Then you’ll really learn a lesson. Thief!’

‘Sunil is not a thief. I am the thief. I found the ball. I knew it was Manesh’s ball. And I told Sunil I just found it, and he must keep it. So I stole your son’s ball. Just like I stole your jewellery. And just like I also took Mr. Mohan’s ornament. So there’s no need for your two families to fight. Themba did it. Ja, the boy did it. I will pay both of you back. But please don’t take me to the police. I’m leaving Reoca now.’

And as Mr Singh moved towards Themba, a cruel glint in his eyes, something amazing happened. Deeno sprang out of nowhere and pushed Mr Singh over. Then he galloped up the road, moving like I’d never seen him move before. Everyone was stunned. Then everyone began speaking at once. Mr. Singh hurled abuse at Themba. My father tried to play detective because he didn’t believe Themba’s confession. Uncle Johnny heard the commotion and came to play peacemaker. And then a few minutes later, we saw Deeno sprinting towards us, holding something in his mouth. Behind him, shouting at the top of her voice was Mrs Singh.

‘Stop that mutt! He took something from the house. From Manesh’s room. He’s a thief, just like his friend.’

And then Deeno dropped what he had ‘stolen’ from Manesh’s room. It was our crystal prism ornament. Mr Singh was stunned.

‘Is this from Manesh’s room, Sunitha?’

‘Er, yes, I think it is. Yes, it is. Oh God. It’s Manoj’s.’

‘You took this Manesh? You took this boy?’

‘I… we… we don’t have that. How come they have it? I… I just liked to look at it.’

Mr Singh unleashed a terrific slap across Manesh’s face. But then Bruno barked ferociously and threw himself at Deeno, tearing into him. I wish I could tell you that Deeno fought the good fight. And eventually won. But he had already played his part. We tried to pull Bruno away, but when we eventually did, he had already delivered the killer bite. Deeno the dog, the lazy mutt, who had leaped to his true master’s rescue, who had sprung the truth upon us, was dead.

Pause.

There was no more punishment that day. The sons acknowledged their wrongdoing. The fathers agreed to deal with it privately. Themba buried Deeno and then left Reoca. But he came back a few times. To visit Deeno’s grave. And to watch me play some cricket matches. (He waves in acknowledgement.)

Themba Dlamini. Who didn’t ask that democracy give him a BMW and a house in Umhlanga. Just a fair chance to be who he could be. Now he runs a garden service company with his cousin and he’s the groundsman for the top cricket club in Phoenix.

And what of the Singhs? They’ve become one of the revered families in Reoca. No more mocking the rich folk from the mansion on the hill. No. Mr Singh gives so generously to charity. Mrs Singh campaigns against the abuse of women and children. And Golden is the local G.P. Everybody knows the Singhs. Only a few people remember Themba. Nobody remembers Deeno.

Lights fade to blackout.

Lights come up on Sunil on centre stage. He is looking at a photo album.

Johnny Naidoo. I’d forgotten how many photos I had of him. So many memories. Ja, Uncle Johnny. A man of many guises. Teacher, advisor, political activist, butcher shop owner. (Pause) He had inspired me to become a teacher.

‘You’ll never feel more complete than the moment you see that spark in a child’s eyes. And you’ll know it was not the media, the internet, even the child’s parents who stimulated the magic. It was you. Your ideas, your compassion, your little nudge. Be a teacher, my boy. Start another fire.’ Then there was Johnny the mutton man.

‘No aunty, I think you must be mistaken. If there’s one thing I know better than poetry, it’s meat. When I sell you mutton, it’s mutton, not lamb and not goat. It must be the masala you are using. Don’t worry, Saturday afternoon I’ll come to your house and make you a nice hot mutton curry on the open fire. Then you’ll make the taste out. In the meantime I’ll give you this cut and cleaned running fowl for free. Ask the ladies about my fresh chicken.’

And of course the ladies would all shout their approval. For them, Uncle Johnny could do no wrong. They were charmed by his wit and grace. As I was. In fact the only time I didn’t want to be around Uncle Johnny was when he bragged about his days as a sportsman.

‘You name the game and I played it. Football, cricket, tennis, gooly-gunda. I used to do high jump too – jump over my mother’s clothes line. Plus long jump – one time I jumped from our yard into my neighbour’s yard and right on top of their fowl-run. Hey, nobody could match me man. But there was no opportunity for Indians in those days. Otherwise your’ll would have been reading about my great feats.’

But there was one side to Uncle Johnny that no one knew about – a side that I was to discover in the early days of the new millennium – Johnny the romantic.

Now romantic gestures were not exactly put on public display in Reoca. I mean, this was a little Indian town. But a few years after his wife had passed on, I noticed Uncle Johnny displaying some extra charm whenever the widow, Aunty Mina, visited the butcher shop.

‘Ja, thanks for your support Mina. No, no the money is correct – I put half a kilo extra for free. I know you like my sausage… er, I mean that chicken sausage. (Pause) Er, you know the other day I got some nice sardines at a good price. I was going to make it this weekend – you know my son and daughter-in-law are going away. But my friend Bobby can’t join me – he’s got a family function. It’s a pity – such lovely sardines – too much for me to eat alone. Er, you got any weddings, er birthday parties, funerals to go to this weekend?’

But the learned Uncle Johnny just couldn’t get around to making an unequivocal invitation. So when he invited me for a secret cigar in our hut one day, I thought he wanted my romantic guidance.

‘I had to get out of the house. Things are getting unbearable there now with my daughter-in-law’s rules. Especially on Tuesdays and Thursdays… when she goes to temple. Then she’s always over-hyped, you know, like she’s getting trance. Hey, I can’t take that woman for long. Leave your shoes outside before you enter the lounge. Don’t watch football after 8pm. You must only walk the dog on Saturday mornings. Don’t do the dishes – your method is all wrong. Hey! I rather run away here and smoke my cigar in peace. I mean, I’m a prisoner in the house I built. I should never have signed it over to them when my wife died. That’s when all this nonsense started. As for my son – he’s a big porte.’

And so Uncle Johnny and I began to meet every Tuesday and Thursday evenings – to eat some hot pizza and smoke a few cigars. And he’d tell me stories – about incidents at the shop, about his adventures with Uncle Bobby, about a world he felt was now fading.

‘Hey Sunil, you should spend some time with Uncle Bobby. I tell you that old man got energy, hey. And he’s a naughty balie too. He used to like to sit on the shop verandah and watch the aunties. This one time, after he just had a heart bypass, he heard Aunty Selvie’s sexy voice. Hey, in a few seconds he went from comatose to pantihose. But she gave him one look and his heart slowed down very quickly. But even he can’t keep up with this other balie, Mr. Arjun. Hey, this uncle is a heavy ou. His vrou’s two sisters came to visit one day. And they stayed way for good. People say they are like extra aunties for the uncle. You know, we call his vrou ma, then her younger sister kitchen ma – cos she’s twenty-four hours in the kitchen, and then the youngest sister, sitting-room ma – cos whole day she only sits and paints her nails.’

Hey, this Mr. Arjun seems like he’s an uncle who wants an aunty for every room in the house. (He chuckles.) Uncle Johnny, what happened to the monthly community gathering your’ll used to have? I can remember going when I was a boy. You know, it was really cool. I remember your’ll used to do lamb on spit and play chutney music. Everyone used to come.

‘Ja, I don’t know why we stopped that. I suppose the next generation didn’t care as much. A lot of things are changing now in the new millennium. Even our shop is not as popular as before. You know Sunil, the Hindu scriptures say this is a bad time – Kaljuk they called it – when children turn against their parents. Many cultures predict this is a bad time.’

But bad time or not, romantic love always finds a way to reveal itself to the world. And so one day, Uncle Johnny and I were interrupted by the laughter of young couple Jason and Jayshree.

‘Hey, stop that kissing now. What you think – this hut is a motel? Jason, I know you’re a naughty boy, but Jayshree, I’m surprised at you.’

‘No, Uncle Johnny, it was just one innocent kiss. We just needed a place to talk. And so I could read my poem to Jayshree. You see our parents won’t let us see each other. No, not because I’m coloured and she’s Indian. But because I’m Christian and she’s Hindu. In fact, her father said that if I don’t stay away from his daughter, he’ll chop off my limbs and screw my legs to my shoulders and my arms to my butt. Just look at me Uncle Johnny. I don’t think I could walk on my hands.’

‘Shut up boy. You talk too much. Let me see your poem. (Johnny reads silently.) Hmm, not bad. A couple of grammatical errors. And your spelling is influenced by American culture. But your words and thoughts are beautiful. Jayshree, do you love this boy? Hmm. I can tell from your look that you do. Spare me the details. Right, Sunil and I are going for a walk. Your’ll can sit in the hut and talk. When we come back in fifteen minutes, your’ll must be gone.’

And they were gone when we returned forty-five minutes later. They left a sweet thank you note. And so we invited Jason and Jayshree back the next Thursday. And the Thursday after that. And after that… They became our special guests in our new pizza hut. Uncle Johnny served the pizza and I provided the entertainment. (Excerpt of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, as Sunil lipsyncs and dances.)

But one day somebody told on us. And their fathers came to our hut. They swore us, and dragged the young lovers away.

‘They’ll find a way to be together again. In time. Nothing can stand in the way of true love. Their parents will have to bow to its majestic power and beauty.’

You know Uncle Johnny. I think its time that you bowed to love’s majesty. I’m tired of seeing you almost being decisive with Aunty Mina. I think it’s time we took this matter from the front of the shop and brought it to the back. I mean, we can’t just let our pizza hut close.

‘Hey Sunil, don’t you try any of your tricks. Or there’ll be no more cigars for you. (Pause) You see Sunil, I can’t be with Mina. She’s very close to her son, Nishaal, and he doesn’t want us to be together. I see how he looks at me when I talk to her in the butcher shop. And Uncle Bobby told me he overheard Nishaal tell his cousin that we shouldn’t be together. Because she’s Hindi and I’m Tamil.’ The old Hindi/Tamil thing. I thought at least that prejudice was starting to disappear. And what a hypocrite Nishaal is. I mean, he’s always talking about how Indians must be united on his cultural programme on TV. (Pause. Sunil becomes more animated.) Nishaal was something of a local celebrity, because he was a presenter on an Indian cultural programme on TV. He always presented in an over-hyped way, in an Anglicized accent which he had picked up while studying overseas. Quite disturbing on a Sunday morning.

‘And so the Maharajs have taken their cultural contribution to a new level. It was not enough to build a temple. Not enough to build a hall. No. Now they’re building a cultural precinct. And yours truly will be administering it. Rest assured, that no one will be left out. Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Gujarathi – we will promote all the languages. Hinduism, Islam, Christianity – all our religions will be respected. We will show the world we are one – way beyond the 150 year celebrations. This is the Indian soul.’ (He does a short, extravagant dance to Bollywood music.)

But I wasn’t going to let Nishaal’s hypocrisy stop my plan. Romance had to return to pizza hut. So I tricked Aunty Mina to come to the hut, telling her my mum urgently needed her advice about a delicate matter. And I told Uncle Johnny I had obtained some Cuban cigars. (Pause) They were so awkward at first – like nervous teenagers. And on the menu tonight, we have chicken tikka pizza and iced tea. Uncle Johnny flashed a ‘I’ll deal with you later’ look at me. And Aunty Mina just said:

‘You’re a naughty boy Sunil. I always knew you were a naughty, beautiful boy.’

And so the old Hindi aunty and the old Tamil uncle came together. But just for three pizza evenings. And then our local culture vulture disrupted our dinner party.

‘It’s a disgrace. My father must be turning in his grave. Go home mother. Before you soil my image of you further. And you Sunil – I can’t… You know when I told Jason and Jayshree’s parents what you were allowing them to do here, I thought their reactions might shock you and make you take stock of yourself. But now you’ve sunk even lower. What are you – a pimp?’

You fucking hypocrite. The only reason you disapprove of your mother seeing Uncle Johnny is that he’s Tamil. Don’t try to put yourself in a morally superior position. This is a simple and beautiful situation.

‘You are interfering with the order of things, little man. This is our way of life in Reoca. A tradition and value system that spans generations. How dare you impose your contaminated beliefs on us? What do you know of culture?’

What do you… But he was not going to listen to me. He grabbed his mother and man-handled her into his car. I rushed after him, determined to show him some very basic culture. (He clenches his fists.) But Uncle Johnny grabbed me in a surprisingly strong grip.

‘Leave it Sunil. There’s another way. A quieter way.’ I wriggled out of Uncle Johnny’s grip. But I still couldn’t move forward. The world became completely silent. I felt my body become light. Suddenly I saw the Hindu Gods smile gently at me. And I saw Angels dance around them. I felt a light inside me. (Sunil falls to his knees and trance like music plays for a few seconds.)

Uncle Johnny’s quieter way included him continuing to talk to Aunty Mina when she visited the butcher shop and to have dinner with her in our pizza hut the next year, on exactly the same day that I had first arranged it – the 22nd of September. And they did it the following year on the 22nd. And again in 2003. And each year Nishaal would somehow be called to Joburg to shoot something for TV on exactly that day.

I didn’t support Uncle Johnny and Aunty Mina’s quiet way. I wanted them to tell Nishaal to get lost. I wanted them to show the world that petty prejudice could not stop sweet love. But I didn’t interfere. I remembered what I saw, and what I felt on the day Nishaal interrupted my scheme. And anyway, my own gung-ho approach to love had brought me little romance and a lot of deception.

And then one day, in 2004, Nishaal got a breakthrough with Zee-TV and moved to Dubai. Aunty Mina refused to leave Reoca. A few months later, she and Uncle Johnny were married. (Pause) So balie, it worked out, hey? You got the girl.

‘Jason will get his girl too. So will you, in time. Sometimes you have to turn around and walk back. Lie down for a while. Let the world rush by. Then you can run again.’

Uncle Johnny Naidoo. The man of many parts. A leader in our community. And my friend. (Pause) He and Aunty Mina still live in their pretty little house in Reoca. And the whole neighbourhood looks to them for guidance. Hindi and Tamil people. They keep the old man busy in his retirement. But on the 22nd of September, he finds some time to meet me in the old hut. To eat some pizza and smoke a few cigars.

Lights fade to blackout.

Lights come up as Manoj is clearing up at the end of the day.

‘Okay, that’s the last customer for today. Phew! What a long day. (He looks outside.) Sharmilla, everyone is gone home. Time to close up. Thanks for staying longer today, love. (He looks around poignantly at the shop and slowly removes his apron.) It was a good day. Another good day. (He steps behind the counter and bends to put away his apron. When the actor rises he is then portraying Sunil. Sunil comes forward.)

Manoj Mohan – the shopkeeper. (Pause) A couple of snotty-nosed kids in the district, including Manesh Singh, used to sometimes tease me: ‘Your father is a shopkeeper, your father is a shopkeeper. He wears an apron. He wears an apron.’ (Pause) Sometimes I think that there are white people and black people who tease their Indian colleagues in another way when they are out of earshot. ‘That ou don’t have to worry. If things don’t work out here, he can go work in his father’s shop.’ Like every young Indian man has a father who owns a convenience store. Or an uncle who owns a take-away. I wonder what they’d say if they knew how it began for us. In our little hut. (Pause)

I haven’t completed this story about my father yet. (Pause) It was in the middle of the recession. After the first two robberies. Uncle Johnny had closed his butcher shop, and advised my dad to do the same. But Manoj Mohan plodded on. After a lull in the first year of the new millennium, business had really picked up again. But then the global economic crisis made its impact on little Reoca too. Still, my father persisted. I remember Uncle Johnny saying one day:

‘Your father is a brave man Sunil. I felt I had to close the butcher shop. But he’s still keeping our special place going. You know, that man is the heart and soul of Reoca.’

The heart and soul of Reoca. I know that the people love my father. But they see him as the kind-hearted uncle who stands behind the shop counter. And listens to their life stories while selling them groceries and goodies. The man who helped create the light of Reoca. They don’t know that he was a biology whiz-kid at school. That he wanted to go to varsity but his parents couldn’t afford to send him. They won’t know how ferociously he defended his son when cynical Uncle Bimal said:

‘You wanna become a teacher. Go to varsity. You won’t make it. Were you can study? You’ll end up a drop-out like your cousin Vinesh. You must just work in your father’s shop.’

‘Get out of my house, you pompous shit! How dare you insult my son? You know nothing about him. You get out and keep your filthy comments to yourself. If anyone in the family tells me you insulted my son again, I’ll make sure that’s the last time you can open your mouth.’

And what if I told our townsfolk he bought flowers for my mum every Friday afternoon. Would they believe me? And I mustn’t forget his Amitabh Bachan impression. At every major family function, after a couple of whiskeys, Manoj the star entertainer emerged.

‘Alright, who’s the lucky lady today? Who’s going to dance with Amitabh?’ (Short Amitabh dance to film music.)

It was the morning after one of these great parties that we discovered my mum had breast cancer. She battled it with that indomitable spirit which always flowed through her veins. And we battled to pay all the bills. My sister tried to help even though she and her husband had just moved to Joburg and were barely making ends meet. I contributed a part of my teacher’s salary. That’s what you did if you came from Reoca. And then the third robbery happened.

‘I gave you everything from the office. And the hut. This is everything left in this shop. Take it. But please don’t beat me up again. (He blocks.) Ow! Stop it! What’s the point? I gave you everything. (He ducks again.) Ja, punish me for not having enough. You idiot!’ (He screams.)

I stood with Uncle Johnny looking at my parents in their hospital beds.

‘You must tell your father to close the shop Sunil. Too many robberies now… well, maybe just for a while at least. I will help you take care of things. This is my old friend. And that’s my sister.’

Don’t worry Uncle Johnny. I mean… you’ve got payments on your new house now… it’ll be okay. We’ll find a way out of this. (Pause) And we did. Dad went back to the shop. And mum went back to doing everything. (Pause)

But then one day she phoned me, very concerned about my father.

‘It’s happening every Friday night Sunil. For the last two months. He runs away for two, three hours. He keeps telling me he’s going to play thunee with Gonaseelan and his friends. But I don’t believe it. I know he’s going to gamble in the casino. I asked Gonaseelan’s mother and she told me Gona is passed out in his room every Friday night. And one time, Francis said he saw your father in the casino. I mean, I know the shop is not doing well, and we got so many bills to pay. But trying to get money by gambling in the casino is crazy. You must talk to him Sunil. I didn’t mind when he sometimes bet on the horses. That was just for fun. But this is unacceptable. You have to talk to him Sunil.’

‘Your mother is getting paranoid. We play thunee on Fridays. Gonaseelan joins us when he’s not pissed. As for Francis, I don’t know what he’s talking about. I think he must have seen my ghost in the casino.’ (Pause)

But he seemed uneasy. And my mum was seldom wrong. A couple of weeks later and I couldn’t resist the pull anymore. On Friday evening, I drove to Reoca and stayed out of sight. Then as my father pulled out of the driveway, I followed him. A few minutes later, he pulled up at the shop, and then walked to the back. I waited for a bit, but he didn’t return to his car. What could he be doing at the back? Wait. Maybe he’s playing an illegal poker game in the hut. No dad. I got out and surged to the hut. I could hear a woman’s voice. I threw open the door. And I saw… I saw Mrs Singh hurriedly dressing. My father had barely managed to put on his shorts. You whores! You filthy whores! This is what you’ve been doing on Friday nights. Doing this bitch! (To Mrs Singh.) You don’t speak! Just get out of here, you hussie! (Motions to grab his father by the hair and pull him out of the hut.) And you get out of my mother’s hut. (To Mrs Singh.) Start running, you whore. And you, you stay down there, you dirty old man. (Pause)

I knew he wasn’t a dirty old man. He was getting old. And he’d been dirty many times. Dirtying his hands. Dirtying his knees. Soiling his old shoes. Always to take care of his family. And up until that moment, he was the best man I’d known. (Pause)

I never thought I’d see you with another woman. You hear about it all the time. So many extra-marital affairs. But I never thought you’d… So old man? Why? Come on. There’s no one else here. There’s just you and me. And God. Why? (Pause)

He didn’t answer me. When I drove off that night, I thought I might never speak to him again. We didn’t speak – face-to-face or in any other way, for about a month. Then one day he did an old-fashioned thing. He sent me a letter. (Sunil reads the letter, but the actor morphs into Manoj and reads it aloud.)

‘I came to your house the other day but you weren’t in. And you’re not taking my calls. So I thought I should write. I didn’t answer you that day. Because I didn’t have an answer. I still don’t know why I went with that moment on that day. Or why I went back to see her again at the hut. I wish it hadn’t been at the hut. But the first time – she had just asked me to meet her to discuss her marital problems. I didn’t know where else to go in Reoca. I can offer excuses, like many men do. I can say that your mother was recovering from her illness, or that the stress of the robberies made me want to escape. But I think that I just wanted to feel different. And for the first time in a long while I didn’t just feel like a shopkeeper. The old beauty queen of the district desired me. And she felt different – not just the rich, dutiful housewife. I think we both wanted to throw away our aprons for a while. I’m sorry son. There’s no justification for what I’ve done. I wish you’d remember me as that crazy guy who’d chase his family around the park on the many picnics they enjoyed together. I think that was the best of me.’ (He stops reading. The actor transforms to Sunil again.)

I met with him, behind the shop. A few days later. He wanted to dismantle the hut and burn it cos he had soiled my mother’s legacy. Don’t burn it. Let it stand. I’ll always cherish the other things that happened in there. So much of my life story resides there. (Pause) Would you have continued to see her if I hadn’t found out?

‘No son. It was fading. My head had stopped spinning. And I began to feel only darkness.’

Darkness in the light of Reoca. That was the last we spoke of it. But not the last time I thought of it. Sometimes I feel enraged.

Sometimes I feel he is weak, pathetic. I say if I had someone special, I would not betray her. And then sometimes I see him dancing with my mum. And she’s holding the flower he gave her every Friday afternoon. I told him he had to tell my mum one day. But not now. (Pause.)

I don’t think I can tell you this story, Mr. Rajpaul. It’s not complete anyway. Maybe I can tell you part of it. (Pause. He walks to the window.) When you write about my father, write about how he was the best shopkeeper in the business. But write also about how he made people laugh with his clever jokes. About how he worked till six pm every day in a shoe factory before we opened the shop. About his dream to visit his sister in India again. About how he held my mum’s hand every night until she fell asleep when she was in the worst days of her illness. Tell the people that he did something. He brought his own light into Reoca.

(Pause)Get well dad. The world is waiting for you.

Lights fade to blackout.

Lights come up on Sunil on centre stage. He folds the newspaper that he was reading.

Thank you, Mr. Rajpaul. It’s a good article. Very honest. (Pause) So may I answer the question which you pose at the end? Hmm – ja. (He opens the newspaper and reads aloud.) ‘Will the Mohan’s return one day to Reoca and will Mohan’s Superette reopen, bringing the townsfolk back to their old meeting place?’ (Pause. He folds the newspaper.)

We’re not running away Mr. Rajpaul. It’s time for a change. My parents have run the shop for twenty-two years. They’ve lived in their little house for nearly forty years. The place needs a complete make-over. Look, I just want them to come live with me for a while. Then they can decide what they want to do. Maybe they’ll be back in Reoca in a year. Maybe Mohan’s Superette will open its doors again sometime in the future. We’ll never completely leave Reoca. How can I never fish again in our river? Hey, Mr Rajpaul? With Uncle Johnny telling me tall tales all day. And I have to come here for the most juicy mangoes in the world. What you say, Mr. Rajpaul? Delicious hey? (Pause) Ja you can tell the people – no one can completely chase away the Mohans from Reoca. (Pause) You know, it’s funny, my parents, like so many Indians, are moving to a formerly white suburb. But the other day, I saw a white couple moving into Reoca. And two black families moved here last year. Now this side is that side; our side is their side; their side is everybody’s side. There are no boundaries. That’s why I said to my ma yesterday – Ma, it’s time for you to be the Murkoo Aunty again. I’m taking our hut and putting it in my backyard. Let it be the hot hut again. Let a new town taste your treats for a while Ma. And let those people’s children meet the Sweet Uncle.

And my dad said to me:

‘I think our ancestors have spoken to you, my son. That’s what your great, great grandfather, Areendum Mohan Rastogi did. He built a little stand and sold his food from there. Chappaties, mielie-meal roti, all kinds of fritters. He sold to his people. And to his oppressors. He never got the shop he wanted. But he carried on anyway. He was a great man.’ (Pause. Sunil is visibly moved.) I can see the light again, Mr. Rajpaul. I can feel it. Oh, it’s beautiful.

Lights brighten, then fade to blackout.

Special on Areendum on far right stage. The set must be manipulated so that the store and the hut have been cleared and it now resembles a room with a bed. The positioning of this scene away from the space of the shop suggests a shift of position for Areendum. He is tending to Biswas. He looks at him for a second, then stands up and turns away.

How can you say your life has meant nothing, Biswas? What is your legacy? I’ll tell you what. A legacy of hope. You cut cane with me every day. And held me when I felt weak. You helped me build a stand. And you made the food with Pallavi and I. So that now we have some freedom. (He points outside.) I am looking at our friends. I can see some smiles. Some of them are walking with purpose. You helped do that Biswas. Your life has created hope for your son. And for my daughters.

We must shout it to the world – I, Areendum, with my wife Pallavi, and my friend Biswas, came to this unknown land. We were fooled by selfish, savage people. They tried to make us forget who we were. But we didn’t forget. We survived. We grew. We dreamed. And we did something. This is our home.

Poignant Indian music plays.

Lights fade to blackout.