16

Reverence for the Archetype

Finding and expressing the genius of place in city, countryside, and cosmos today.

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

Alexander Pope, eighteenth-century poet and translator of Homer’s Iliad, wrote the poem as a letter of advice to his west London neighbor Lord Burlington who was creating a garden for his new English Palladian villa. In counseling him to call upon the “genius of the place,” Pope was referring to the ancient Greek belief that in each person, place, and object there resides a daemon, a genius, a guardian spirit containing the essential nature of that to which it is attached. While not coterminous with the object of its protection, the genius (plural genii) exemplifies and exposes the true inner nature of that to which it is joined. Recognizing the genius meant understanding the essence, identifying the archetype. To know one’s own genius requires contemplation and meditation. “The unexamined life is not worth living” and “Know thyself” are attributed to Socrates, but the ideas probably have even more ancient roots. Finding and understanding one’s genius was to the Greeks evidence of wisdom.

The genii were to be cultivated and propitiated through worship and sacrifices lest their spirit punish the ones they were meant to guide and protect. Throughout the ancient Greek countryside temples were erected in sacred places where a genius was perceived to be at home. The natural site around the temple was not altered, the temple signifying that it was a holy place. Mountains, springs, seascapes, islands all had their genius loci—genius of the place—and were especially revered locations.

Consult the genius of the place in all,

That tells the waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’ ambitious hill the heav’ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the vale;

Calls in the country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks, or now directs, th’ intending lines,

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

—Alexander Pope

The Greek temple builder and later landscape designers sought to probe the meaning of a place to determine the character and true nature of the resident genius. Historian William Howard Adams wrote, “Only after the spirit was divined could the architecture itself be introduced into a holy partnership with the existing features of the topography.”

The Greeks were not the only people to seek the unique nature of a site. Creators of ancient pyramids, henges, and mounds put their knowledge of the workings of sun, moon, and stars into a particular place. In recalling these practices, Alexander Pope was enjoining gardeners to seek, like the ancients, the unique qualities of a site.

Contemporary landscape architects have looked back to archetypal land forms and forward to present-day places, events, and ideas to find genii. They also look within, for there is a genius not only in the place they are to design, but within themselves. Each has his own inner spirit to call upon and uncover. Each brings his own time and place—the historical moment—and his own life history. It is the genii of site and person that make landscape design an art form.

You, too, proceed! . . .

Call forth th’ ideas of your mind,

(Proud to accomplish what such hands design’d)

Bid harbours open, public ways extend,

Bid temples, worthier of the God, ascend.

Chicago, Illinois

Carl Sandburg’s poem captures the essence of the brawny city of Chicago. So does Lurie Garden, part of Millennium Park, a short walk from the west shore of Lake Michigan, across the street from the new modern wing of the Art Institute of Chicago and adjacent to the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Like Sandburg’s poem, Lurie Garden pays tribute to the great midwestern hub, America’s third largest city.

The largest green-roof garden in the world, Lurie models sustainability. Sitting atop underground parking garages, the two-and-a-half-acre garden uses a minimal amount of water in its water feature and for its hardy perennials, sixty percent of the plantings native to the state of Illinois.

The competition held to select the garden design was won by Kathryn Gustafson, landscape architect, whose work in public parks in Europe includes the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain in London’s Hyde Park. For Lurie, Gustafson worked in cooperation with lighting and set designer Robert Israel and Dutch plantsman Piet Oudolf. Together they set about discovering the genius of Chicago and expressing it through their art.

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders.

—Carl Sandburg

A first problem to be addressed was the proximity of the garden site to the great lawn of the music pavilion where large audiences gather for summer music. How might Lurie Garden be protected on concert nights from the thundering herds seeking to stake their claim for a place to sit? From Sandberg’s poem, Chicago has become known as “the city of big shoulders.” Gustafson used an enormous evergreen hedge shaped like shoulders to separate the pavilion and lawn from the garden. Planted within a black steel frame, it gives a sense of enclosure at the north end and west side of Lurie Garden.

The fifteen-foot-high “big shoulder” hedge of both needle and broadleaf evergreens separates the great lawn of Millennium Park and the music pavilion from Lurie Garden. Boardwalk and runnel bisect the garden diagonally.

Piet Oudolf and his wife, Anja, welcome visitors for open days at Hummelo, their home and native plant garden in the Netherlands where Michael Garber photographed him.

The garden is divided by a “seam,” a five-foot-wide runnel with periodic pools, a narrow wood pathway almost at water level for sitting and, on a summer day, dangling feet. Slightly higher is a wide boardwalk leading the stroller diagonally across the garden and up the slight incline from southwest to northeast. It traces the path of a subterranean seawall that once was the boundary between the marsh at Lake Michigan’s shoreline and the city.

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I

have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer Yes it

Is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the

faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

To the east of the boardwalk lies the Dark Plate, a raised garden bounded by native limestone walls. It is planted with trees and shade-loving plants including ferns, angelicas, and broad-leaved species, chosen by Oudolf to recall the marshy beginnings of the city. But what visitor could fail to be reminded of Chicago’s past of corruption, crime, gangland killings, and the grinding poverty?

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing

so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on

job, here is a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities. . . .

Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse,

and under his ribs the heart of the people,

Laughing!

The Light Plate on the west side of Lurie looks to a bright future.

Lurie Garden harbors at least twenty-seven species of birds. Here, in the Dark Plate, a sparrow is well disguised.

The Light Plate looks to the future. Without trees, the sun highlights the amsonia, asters, bee balm, bottle gentian, butterfly weed, coneflowers, eulalia, fountain grass, goldenrod, little bluestem, prairie dropseed, northern sea oats, rattlesnake master, skullcap, and switch grass which are among the thirty-five thousand perennials in 240 varieties in Lurie Garden.

Lurie Garden has won various awards for its adherence to the best principles for sustainability and as a public space. It might also win a design award for uncovering, as did Sandburg, the genius of the place, Chicago.

National September 11 Memorial

New York City, New York

Recently out of college, Welles Crowther had his first real job as an equities trader when he put to use another set of skills that he had long been cultivating. As a child he had set his heart on becoming a fireman. Acquaintances knew of his dream and of his attachment to the red bandanna his father had given him as a child. Ever after, Welles kept a bandanna in his pocket. In high school, he volunteered with the local fire department, learning firefighting and rescue techniques. On September 11, 2001, when the World Trade Center in New York was attacked by terrorists, he courageously put those skills into practice, guiding people from the building’s upper floors to the street below. He died in that effort. Soon after, survivors came forth to tell their story of the young man wearing a red bandanna across his mouth and nose who, it was later learned, led eighteen people to safety.

Peace for those who witnessed the imploding towers would not be easily won. The acts that killed almost three thousand and brought down the nation’s symbol of ingenuity, skill, and financial strength left survivors angry, despondent, and immeasurably sad. The memorial planned for the site would have to speak deeply, profoundly, and realistically to the city, nation, and the world as people from every continent, many religions, cultures, and belief systems had died. Grieving visitors to the memorial would bring their widely varying thoughts and feelings. The instructions to those submitting designs for the competition were that there be open, public space equal to that of the memorial itself.

Architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker won the competition. Arad, an Israeli citizen educated in the United States and living in New York where he was designing police stations, was in his early thirties. Peter Walker was over twice his age, bringing his education at the University of California Berkeley and the Harvard School of Design and over forty-five years of design experience to the task.

They submitted a plan that called for a large forest in the midst of which lay two large reflecting pools on the footprints of the destroyed Twin Towers. Set thirty feet below the surface plane, the two one-acre pools are filled by water flowing down the sides of the pits, creating the largest man-made waterfall in the United States. In the center of each pool a square funnels the water farther down into what appears as a void, as if, beyond human sight, to the center of the earth, expressing the depth of sorrow. Around the parapets of the pools the names of those who perished are incised in bronze.

Rushing water spilling through the weirs flows down the sides of the reflecting pool into the abyss below.

In what are called “meaningful adjacencies,” the names of those who perished are grouped by the communities through which they were joined in life and, most probably, in death.

Peter Walker’s landscape design called for densely planted swamp white oak trees (Quercus bicolor) which grow to a height of fifty to sixty feet. Native to northeastern America, they are durable street trees. As they mature, they will in summer provide shade, reduce the heat absorption by the plaza, and through the transpiration of the leaves, cool the air. The memorial grove is planted so that looking in one direction it appears as a natural forest; in the other as an allée. In September the trees turn a golden orange, making peaceful the colors of fire. The park and the edges of the pools are on a flat plane and the surface of the park allows for a variety of activity from quiet rest to public gatherings including the annual reading of the names of those lost.

The Arad and Walker design is named Reflecting Absence, and it is absence that visitors experience as they remember the void of Ground Zero and think of those who are gone. The design is minimalist like abstract Japanese Zen gardens, the elements calling forth to the reflective person image after image, allowing the individual to explore a wide range of feelings and ideas.

The design team chose three elements universally experienced and fundamental to human understanding of life. The forest is a place of danger but also a source for shelter, food, and fuel, home to sometimes kindly, sometimes avenging gods. Water, too, is elemental. From the womb humans know its healing and cleansing powers, use it in religious ritual, and follow its natural paths. But water, too, can wreak destruction. The third element is the geometric shapes, ancient vehicles for spiritual guidance. The pyramids of Egypt and Mexico and prehistoric sites such as Stonehenge, Newgrange, and the spiral mounds of Ohio are among the man-made structures that point to the heavens, its planets, and stars. At the National September 11 Memorial the reflecting pools allow us to look down and simultaneously through the reflection look above, into the depths of sorrow and to the heavens for hope.

The proud towers are gone as are many who came to them to work. Like legendary heroes, they have disappeared, leaving behind the stories of their lives. The National September 11 Memorial calls the visitor from New York City or afar into the mysteries and sadnesses of life, but also into its hopefulness. Its simple dignity expresses nobility, heroism, and compassion as characteristics of the genius of this place and of the people remembered here including Welles Crowther.

The curves of the surrounding mountains are echoed in the designed contouring, the meadow forms, and the paths.

Mountainville, New York

Storm King was begun with the idea of bringing together the wonderful landscape of the Hudson Highlands with the paintings that made the area famous. The Hudson River school of painters who contributed to the social revolution that was occurring in the valley early in the nineteenth century had, with their art, made people aware of America’s natural beauty. But in the end the wedding at Storm King was with another visual art form of a different period. The five hundred acres of forest, hills, lake, and fields have become the largest sculpture park in North America, ideal for displaying the huge abstract pieces that, at mid-twentieth century, were being created. At Storm King Art Center the surrounding tree-covered mountains and hills are the walls, the fields the floor, and the sky the ceiling of this outdoor museum. But to show the art to full advantage the landscape itself required sculpting.

Hearing the sound of thunder rolling down the river in a Hudson Valley summer storm, local residents say the giants are playing ninepins. Mark di Suvero’s Mother Peace might be among them.

In 1958 businessman Ralph E. (Ted) Ogden purchased a Normandy-style stone château at the top of a hill near Storm King Mountain. With the encouragement and help of his son-in-law H. Peter Stern, Ogden made his first purchases of sculpture, Henry Moore’s Reclining Connected Forms and thirteen David Smith pieces. Other sculpture was acquired so that by the end of the 1960s Storm King was known to the creators of monumental sculptures as a desired location for their work. Few museums had space for pieces their size, the number of building atria and public plazas was limited, and almost no place could accommodate more than one piece.

Mark di Suvero was one of the artists pleased to have his work chosen for Storm King because his sculptures, made of steel beams and girders, are gigantic. However admired he is as an artist, his sculptures would appear crowded in most locations and might even have been left homeless. At Storm King his pieces, seen from a quarter of a mile away, have ample room, giving the impression that they were born in their spot.

Supreme among the advantages of Storm King for artists is that the location of a sculpture and its surround can and will be altered to create the best possible site. Landscape architect William A. Rutherford Sr., working closely with the sculptors, designed and engineered the contouring of earth to show a piece to full advantage. He saw the wisdom of using no plinths or artificial platforms so that the works appear rooted as part of the natural setting. In some places land was leveled to provide a firm base, while a hill was created for Alexander Calder’s stabiles to march upward. For di Suvero, who prefers his pieces to be seen from above, Rutherford removed trees to create the wide spaces necessary for viewing from close-up or afar.

For Isamu Noguchi, the request from Ogden and Stern that he create a site-specific piece proved irresistible as he was allowed to choose his spot and his subject with the promise that the land would be shaped to his creation. He selected a rise near the château, and for this site he sculpted his Momo Taro. Made of Japanese striated stone, the forty-ton work is based on a Japanese fairy tale of a child who comes to a childless couple from the inside of a peach pit. The large hole in the sculpture, suggesting the now vacant center, allows visiting children to climb in and out as Noguchi intended, perhaps pretending they themselves are the dearly wanted child.

Sculpture is not just placed on the grounds of Storm King, but rather becomes one with the landscape. The genii of the place and of the artworks are joined. Throughout the valley, farmers have cleared their fields of loose rocks by constructing dry walls. Artist Andy Goldsworthy made such a wall 2,278 feet long, his serpentine shape winding through a grove of trees, slithering like a snake into the water, then emerging on the other side as if it had continued on the bottom of the pond, and ending at the New York State Thruway that passes nearby.

Artist Maya Lin has made a landform at Storm King that makes the landscape and the art form completely one. Most famous for her Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. which cuts into the earth, here she created Storm King Wavefield, raising the “waves” from the ground, thereby making the contoured earth not a setting for sculpture but the sculpture itself.

Today Storm King Art Center holds over 125 pieces and is surrounded by more than two thousand acres protected from development. The concept for the sculpture park developed over the years from that of providing a setting for large sculpture to that of commissioning site-specific works and finally of using the earth itself as the artist’s medium. Peter Stern reports that many visitors commenting on the beauty of the natural setting refer to God’s handiwork. Stern reminds them that the landscape architect should receive credit as well. Bill Rutherford shares with Capability Brown both the landscape park style and the experience of having his work mistaken for that of the Creator.

Now called Storm King Wall, the original title of the Goldsworthy piece was The Wall That Walked Into the Water.

Maya Lin sculpted the earth itself for Storm King Wavefield.

Toronto, Canada

Prodigy Yo-Yo Ma began playing Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello as a young child. At midlife when he had become a word-famous cellist he conceived the idea of uniting various art forms. He invited artists in different media to explore the meaning of the Bach suites and imagine how they might interpret them in their own art. For landscape design, he approached fellow Bostonian Julie Moir Messervy, whose book Contemplative Gardens had intrigued him. She reports listening again and again to his recording of the First Suite before writing down her thoughts. “The whole notes feel like a stopping place in a garden, the eighth notes and sixteenths feel like a path,” she wrote in her initial response to Ma. Her combination of curved and straight lines in the Toronto Music Garden would echo those seen in the cello itself.

Soon the project began to take shape. As her ideas crystallized, Yo-Yo Ma and Julie Messervy found an interested mayor in David Miller of Toronto. Having already begun developing as a park a two-and-a-half acre sliver of land on the harbor, he saw the role that a music garden might play in the needed revitalization of the Lake Ontario waterfront and how it might shape the city’s culture and future. He understood that Yo-Yo Ma’s idea embodied in Julie Messervy’s design would create no ordinary park but rather one that would attract both city residents and tourists. As the garden developed, it seemed that music had always been a characteristic of the site’s genius.

Bach choose for the First Suite five dance forms, allowing him to display a great mélange of musical forms. Messervy in turn created a garden of rooms, one for the Prelude and another for each dance, providing a medley of landscape styles in a small space. Granite boulders with trill-like veins of red feldspar from the Canadian Shield, rounded from constant tumbling in glaciers ten thousand years ago, unite the various sections. Three hills allow harbor views as garden visitors move upward and downward step by step just as do the notes in a Bach composition.

The visitor may rent audio equipment to hear, while touring the garden, the Bach cello suite played by Yo-Yo Ma. The Prelude begins at a short waterfront walk beside a meandering stone brook. Two lines of straight native hackberry trees suggest a staff of music. The path, with spirals brushed into the concrete, winds upward. Rocks are hugged with matting plants, the “music” punctuated in spring with tall lupines and irises.

To the left is the Allemande, a seventeenth-century French court dance taken from a German folk tune. In the garden, the main trail backed by birches leads steadily uphill to a clearing where stones appear as a group of whole and half notes. Small curves off the main path, like steps of a dance, are enlivened by seasonal plantings—daffodils in early spring, foxgloves and meadow rue in late spring, alliums and balloon flowers in summer, and asters and grasses in fall.

The lively Courante would entice even the most devoted office worker to quit his desk.

Turning right, the visitor comes to the sprightly Courante. Hearing the Courante in Bach’s First Suite, Messervy’s daughter imagined “a meadow of colorful wildflowers filled with hummingbirds and buzzing bees.” Here two paths spiral uphill to a maypole with ribbons that, although made of iron, appear to flutter in the wind, meeting in the center as “dancers clasping hands.” Here real flowers— artemisias, asters, buddleia, coneflowers, and Russian sage—enliven the scene, as colorful as the costumes of the imagined dancers.

The Sarabande is next, a contrast to the energetic Courante. As a musical form, the sarabande, in triple meter, is stately and accompanied a popular dance form in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The walls of the Sarabande garden room are mainly evergreen with a few deciduous trees of blue, bright green, and plum. At its enclosed and quiet center are flat-topped rocks for resting, reading, and contemplation.

The Menuett crowns the highest hill and is the location for larger musical performances. At its center is an iron pavilion with tendril-like decoration. Roses line either side, with native crabapple trees defining the circular space. On either side framing the pavilion, two weeping trees appear as dancers bowing to each other.

Finally the Gigue’s terrace stairs lead downward to the water’s edge. Children especially dance down the grass steps, as if doing a jig, the dance form on which the Gigue is based. At the base of the steps is another venue for music, the steps providing seating. A huge weeping willow lends a wistful note, for gardens, like music, are fleeting, their ephemeral nature making the experience all the more cherished.

Shakespeare Garden at Vassar College

Poughkeepsie, New York

Matthew Vassar, founder of the college that bears his name, would not have been surprised that, in 1916, the then-women’s college began a garden planted with flowers and herbs mentioned in works by Shakespeare. He believed that students should be immersed in all forms of art and had collected Hudson River school paintings for their edification. And he had worked with Andrew Jackson Downing on landscape design, hiring Downing for Springside, his own home and surrounding property in the mid–Hudson River Valley. The idea of students learning simultaneously about the history of garden design, horticulture, and literature would have won his nod of approval. How pleased he would be that through a garden, the genius of Shakespeare has had an altar at Vassar College for over a century.

Students and faculty have worked in the Shakespeare Garden since its inception, including in the 1940s.

The idea for the garden came from Henry Noble MacCracken, the college president and distinguished professor of English. Having written a scholarly commentary on Shakespeare, he wanted a way to recognize the 1916 tercentenary of the bard’s death. And the idea of bringing together for the project two disciplines fit with his progressive ideas, similar to those of his contemporary, the philosopher, psychologist, and education reformer John Dewey. Both believed that school and life experience, study and action, should be of a piece, each informing and reinforcing the other.

The students in Miss Winifred Smith’s class in Shakespeare drew up a list of all the plants mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. Miss Emmeline Moore, who taught botany, took charge of receiving alumnae contributions of bulbs, roots, plants, and seeds, making sure each donation was on the list. In addition they obtained seeds from the Shakespeare garden at his birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Their work, the Shakespeare Garden at Vassar College, was to be the second such garden in the United States, opening three months after that in Central Park. In the century following, the Vassar garden went through periodic renovations as all gardens must. In the 1920s redesign was part of a campus-wide landscape remodeling. In 1977–78 under the direction of a botany professor, students planted 3,700 bulbs, a professor of English attesting that all were mentioned in the Shakespeare corpus. At the bard’s four hundredth anniversary in 2016, the garden was in the midst of a renovation and extension after the construction of a new building nearby.

The site chosen for the Shakespeare Garden and where it remains today is adjacent to Fonteyn Kill (stream) that runs through the campus. It was undoubtedly chosen with Shakespeare’s famous passage from Hamlet in mind, in which Gertrude describes Ophelia’s drowning to her brother, Laertes:

The Vassar College Shakespeare Garden today, backed by willows “aslant a brook,” is designed as would have been an Elizabethan garden.

There is a willow grows aslant a brook

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream.

There with fantastic garlands did she come

With crowflowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cold maids do “dead men’s fingers” call them.

Other flowers and herbs adorn today’s garden. Culinary and medicinal herbs in neat squares are labeled with quotations from the plays. The garden’s expansion now includes plants grown in England in the seventeenth century as well as those mentioned by Shakespeare. The square and rectangular raised beds of brick are consistent with gardening practices in Tudor England, as are the topiary spheres, wooden arches framing entrances, and patterns in the brick walks. The newest plan calls for knot gardens, smaller than but similar to those at Hatfield House, Queen Elizabeth I’s childhood home. Bay, basil, chives, fennel, fig, mint, oregano, pansies, purple sage, rosemary, strawberries, summer savory, tarragon, and thyme are among the plants in the extended garden.

For the Shakespeare aficionado, thyme recalls Oberon’s memory in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “I know a bank where the wild thyme blows.”

A sign in the garden reminds the visitor of Salisbury in Shakespeare’s King John who reasons that “To guard a title that was rich before . . . / To gild refined gold, to paint the lily. . . / Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.”

The Shakespeare Garden is a peaceful place for students, faculty, and visitors to read or stroll and is itself a source of learning. Matthew Vassar and President MacCracken would have agreed that the addition of history in today’s garden further enriches education, appropriate for a location that has been and remains a temple of learning and scholarship.

Dumfries, Scotland

The revelations of modern physics and biology may seem unlikely to inspire the design of a garden, but Charles Jencks did not think it so. In the images generated on computers in the last quarter of the twentieth century and those seen through the Hubble Space Telescope, he saw new ways of understanding the universe. Whether too minuscule to be seen even with the aid of a powerful microscope or galaxies light years away, these images challenge any notion that may remain that the universe is static and linear. What they showed to Jencks is a wavy, squirmy, jumping, leaping, romping, ever-moving, ever-changing world. He would honor this newly perceived truth, this genius, in his garden.

In addition, advances in science raise anew age-old questions about life, its origins, and its meaning. Does the universe have purpose or is it directionless? Was it created and is it governed by laws or accident? These are questions asked by modern science and by Charles Jencks in the Garden of Cosmic Speculation. Ironically, in creating a garden expressing these new concepts and old questions, Jencks was following in the footsteps of his seventeenth-century predecessors, notably André Le Nôtre. Although Jencks’s view of the universe opposes that of the linear and static vision of Enlightenment thinkers, he asks in his garden the same questions as they did, using contemporary science just as the geometric designers used the science and mathematics of their day.

All of this might seem ponderous but the garden is certainly not so. Just as many true scientists find childlike delight in new discoveries, the Garden of Cosmic Speculation dances with charm and wry humor as it presents the newly seen world.

The yew and arborvitae hedges of Cosmic Speculation are trimmed in various ways to suggest the wavy, moving universe. The boar is the work of Elizabeth Frink.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Jencks graduated from Harvard and then, in the period after the innovations of Walter Gropius, the Harvard Graduate School of Design. From there he moved to London where he studied architectural history at University College, earning the PhD. He wrote about contemporary architecture that broke with the modern style and was an early theorist and operative in postmodern design. An analyst of the contemporary world, he saw before most others the changes in our culture and what they meant. It is not surprising that his garden reflects the newest knowledge and theories of cosmology while posing eternal questions.

The plan of the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, by Charles Jencks, updated in 2010, shows twenty areas designed around “cosmic and other ideas of a public nature.”

Charles Jencks, left, and head gardener, Alistair Clark, confer on the next garden project.

In creating his garden Charles Jencks had skilled partners and aides. His wife, Maggie Keswick, was a garden connoisseur. As a child she was shuffled back and forth between the United Kingdom and China where her father was a business tycoon. She wrote a definitive book on Chinese gardens and wove her interest into the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, giving Chinese garden tradition a new twist. From Jencks’s description of the way they collaboratively examined concepts, each sketching how the ideas might look when realized, it is clear that the conversation between them was as lively, intellectual, and amusing as the garden they created.

Highly trained horticulturist and skilled gardener Alistair Clark has worked with Jencks since the 1980s. Renowned scientists and architects have explained and advised. Skilled craftsmen have fashioned gates and sculpture, working their aesthetic magic for the Garden of Cosmic Speculation.

When Charles and Maggie decided to make Scotland their home, they moved into Portrack, her parents’ home, a white Georgian farmhouse built in 1815, near Dumfries, southeast of Glasgow. Much of the property was a natural swamp, a challenge for any gardener. But Maggie, perhaps thinking of Capability Brown at Blenheim, began by creating lakes. Never far from her China upbringing, Maggie saw in the shapes of the lakes and the curving contours of the land the mouth of a dragon about to ingest a snake. In 1989 the Garden of Cosmic Speculation began to take shape and has continued its evolution ever since.

As Charles turned to modern science, he and Maggie also looked backward to the dawn of human landform-making, molding archetypal forms at the garden’s heart. A snail mound reminds visitors of, says Jencks, “the poetics of going slow.” Below, a spiral extends from the land into the lake, the curving lines fit within the divided and subdivided golden rectangle and demonstrating how humankind has stylized natural forms. The quiet bodies of water with their curved and fluid crescent shapes convey peacefulness, as do the moon ponds at Studley Royal.

The double helix appears in a section of the garden that celebrates dna and the senses. Organized in geometric patterns, each of the squares bounded by box hedges highlights one of the five senses. Charles and Maggie also added a sixth sense, woman’s intuition. The brick-lined pebble paths separating the sections have a Chinese feel in their patterns. In one called the Drunkard’s Walk the pattern careens from side to side as if arguing a cosmic question.

Countering the Garden of the Six Senses is a copse that Charles and Maggie named “Taking Leave of Your Senses.” In its midst The Nonsense, a steel frame of a building, was inspired by a structure at Bomarzo and is similarly disorienting. The stairs here lead only to frustration as a beam prevents reaching the view at the top. Jencks calls his structure “a hybrid medium somewhere between sculpture, literature, architecture, and landscape,” a style that he would later label “cosmogenic art.”

“Taste” at the bottom of a double helix is exhibited with Warhol- or Lichtenstein-like lips rising above the ground that is planted with luscious red strawberries.

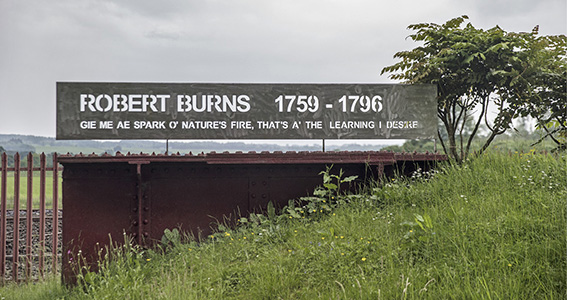

Scotland’s national poet “Rabby” Burns is remembered with his words, “Gie me ae spark o’ nature’s fire, that’s a’ the learning I desire.”

The red Jumping Bridge is actually two bridges rising above the stream like traditional Chinese bridges, here appearing to leap over the water. The walkway connecting them tilts, giving the walker a brief Sublime thrill of imbalance.

The bridges lead to the Temple of Scottish Worthies. On one side, following the railroad line that runs through Portrack, is a series of metal signs with cutouts of the names, dates, quotations, or accomplishments of great Scots, including Robert Adam, David Hume, James Hutton, Walter Scott, Adam Smith, Thomas Telford, and James Watt. In the line of trees opposite hang long red metal banners with the names of other Scottish notables beginning with Agricola, the Roman general who brought Britain into the Roman Empire. That his is also the name given to a mind-challenging board game whose object is to build the best well-balanced farm makes him especially appropriate for inclusion in the Garden of Cosmic Speculation. The temple is both a serious reminder of the Scots who have contributed significantly to the world’s intellectual and artistic legacy and a satire of the solemn eighteenth-century Temple of British Worthies at Stowe, just south of the border in England.

Scientific references and representations abound throughout the Portrack landscape. There is a black hole, a fractal garden, a copse of quarks, a display of the Standard Model with the Higgs boson, soliton waves and gates, and Einstein’s theory of relativity. A bench bears a quote from Linnaeus—“Nature does not proceed by leaps”—with the added words of Jencks, “but by cometary jumps.” And there is humor: a stumpery of look-alike tree stubs named Dragon Teeth, lines of turf strips alternating with gravel that make Broken Symmetry, and a bench with an Art Nouveau look that has no straight lines titled Non-Euclidian Furniture. Jencks identifies the Universe Cascade, portraying the “inflationary” universe as understood by modern science as the garden’s heart. Its steps emerge from the brown quantum foam at the water table below the pond, widening as they reach the top to represent the latest expansion.

The two parts of the Jumping Bridge and walkway give a little when walked upon so that the visitor not only sees but feels the moving universe.

All of this and more is in a setting using both geometric forms and the planned natural style. Consistent with Alexander Pope’s advice, Jencks and Keswick consulted the genius of the place, incorporating and reinforcing by their design the natural contours of the Scottish hills, ridges, and lakes, perhaps even thinking of the serpent that legend says lives in the not-too-distant Loch Ness. Jencks says of the garden he and Maggie created that its speculation about nature and our nature is “to celebrate the beauty and organization of the universe, but above all resupply that sense of awe which modern life has done so much to deny.” “Perhaps,” he concludes, “in the end neither man nor the universe is the measure of all things, but rather the convivial dialogue that comes from their interaction.”

The water chain at Villa Lante tells of man’s progress from primordial beginnings to civilization. The Universe Cascade depicts theories of the birth and life of the universe. The structure at left recycles “dark energy down its membranes” into the quantum foam, “the seed for galaxies.” The ever-broadening steps, center, represent the universe “expanding faster than the speed of light.”

When Maggie Keswick died of cancer in 1995, mourners climbed to the top of the mound, leaving flower offerings there.

Wiltshire, England

It was only a small house party. Three people who had collaborated for twenty years gathered at Shute House in the summer of 1992 to toast the achievement that they now declared complete, an achievement the gardening world had declared a masterpiece. Sitting that evening at the head of the water cascade, they recalled the garden’s evolution and relished its success in capturing the ideas that Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe had developed in his long and distinguished career as architect, landscape designer, and intellect. “Like the portrait painter, the landscape designer needs to be a psychologist first and a technician afterward. He needs to dig into the subconscious,” wrote Jellicoe of his design concept.

Artist Michael Tree and his wife Lady Anne were the owners of Shute. He had known Jellicoe since childhood when the landscape architect designed his parents’ gardens at Ditchley Park. She, a Cavendish of Chatsworth, would be the plantswoman for Jellicoe’s design. Even when they were considering the purchase of Shute House in 1968, the Trees called Jellicoe for his assessment. Jellicoe, born in 1900, had just retired, but his walk around the Shute property convinced him that residing in the neglected, overgrown, and undistinguished property was a genius that his now mature concepts, if made concrete, could reveal.

The original plaster herms have been temporarily replaced with busts of Zeus, Apollo, and Neptune until finer representations of the original authors can be found.

His career had been rich and varied, and he was recognized as Britain’s foremost landscape architect. As a student at the Architectural Association School of Architecture he had traveled to Italy with J. C. (Jock) Shepherd where they studied Italian gardens and wrote their book Italian Gardens of the Renaissance. He later returned to the British School of Rome and traveled extensively in Europe, writing a book on Baroque gardens. His other seminal works included the three-volume Studies in Landscape Architecture as well as Water: The Uses of Water in Landscape Architecture and The Landscape of Man, the last two with his wife, Susan Jellicoe. He was always studying the fine arts, especially painting, and served as a trustee of the Tate Gallery.

As a landscape architect, Jellicoe had won important commissions including for the surroundings of the Royal Shakespeare Theater at Stratford-upon-Avon and the John F. Kennedy Memorial at Runnymede. He was named principal of the Architectural Association School of Architecture, elected president of the Institute of Landscape Architects, appointed cbe, and then, while working on Shute House, was knighted.

When he began work at Shute, he was able to bring all of these interests and experiences into his design—and something more. It was the theory of Carl Jung that would provide Jellicoe with the integrating principle. Jung had taken his place beside Sigmund Freud as one of the two most influential psychologists of the twentieth century. Jung theorized about the motivations of and influences on human behavior, giving the name the “collective unconscious” to shared human experience. Jung believed that centuries upon centuries of archetypal images have entered our subconscious and there reside. Jellicoe’s concept was to bring the ideas and history of mankind’s molding of his environment to light, not on the analyst’s couch but in a garden. He knew that realizing such a concept would take years. Michael and Anne Tree assured him he would have the needed continuity. Shute would be the laboratory for his dreams.

Jellicoe was drawn to Shute by the plentiful water and by the site that recalled his formative time in Italy. The house, atop a ridge with the land easing downward on either side, allows views out to the surrounding countryside, as at the Villa Medici at Fiesole.

Abundant springs would allow him to use water as the central and binding element just as in the Villa Lante, his favorite Italian garden. There Ovid’s myths telling of the rise of human civilization from primordial beginnings are united by water. Educated as he was in classical literature, Jellicoe understood the use of water in its various forms as symbol and metaphor and he acknowledged the place of water in our subconscious. “Whether we are watching the ceaseless movement of the waves on the seashore or the eddies on the surface of a pool, or reflection on a calm day, the fascination of water seems endless,” he wrote.

The sound of the treble chute is joined by the alto, tenor, and bass as the formal stream tumbles downward.

A nineteenth-century canal is the first body of water to come into view. At the far end in the enclosing hedge Jellicoe sought to embed herms of Ovid, Virgil, and Lucretius, commanding attention and reminding the pilgrim of their works: Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Virgil’s tale of the journey of Aeneas from Troy across the Mediterranean to arrive at last at the site of Rome, and the cosmology described by Lucretius in his extensive poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things).

From the canal, the water divides into two streams, the one formal, the other free-flowing in the style of the English landscape park. Here classicism and Romanticism point to the critical juncture of landscape design in Western history, summoning our collective unconscious. To carry the water downstream in the formal garden, Jellico used a rill punctuated by geometric forms, vaguely suggestive of the ancient Court of the Lions at Alhambra although instead of circles Jellicoe used for his basins a square, a hexagon, and an octagon.

Copper undulations set in concrete make the descending water sing. The theory is that the more the water is broken up the higher the notes will be. The “dimples” are reduced in number at each cascade, making music in a lower tone at the bottom of the cascade. The goal was to create a harmonic chord. Just as Jellicoe admired the many clever water features at the Villa d’Este including the organ fountain that played music, d’Este’s designer Pirro Ligorio would surely have applauded Jellicoe’s musical cascade at Shute.

The Romantic planned natural branch of the stream is lush and gently curved. Rhododendrons and weeping willows soften one bank and are reflected in the water. Here nature appears released from any straitjacket of geometric lines, fostering emotion over reason. Capability Brown would have been pleased with the look that included turf on the opposite bank kept clear of any plants at the water’s edge. Jellicoe described a Brown landscape as a pure abstract form, “empty of an idea beyond the primary concept . . . universal and dateless.”

The two streams reunite at the bottom of the incline as they near the bog garden. Here Jellicoe employs Edmund Burke’s concept of the Sublime with a touch of the mysterious, releasing the imagination to explore and feel the unknown. He described the purpose of the Shute garden as that of replenishing the mind itself. By bringing together the divergent ways of seeing and handling landscape in the past, he has made apparent and conscious the genius of past land-shapers and their effect on our experience of land and nature.

Boughton House

Northamptonshire, England

Landscape architect Kim Wilkie called his book Led by the Land, but he named his design at Boughton House Orpheus, after the musician sublime who, Virgil said, “led the trees.” Seeking to reclaim his beloved Eurydice from death, Orpheus was almost alone among mankind in voluntarily braving the underworld with the hope of returning to earth. With his enticing lyre he persuaded the god Hades and his winter wife, Persephone, to release Eurydice from captivity. But leading her upward to the world of light and life, Orpheus could not obey Hades’ simple injunction to look ahead, not back, and in his act lost his beloved forever.

When Lord Dalkeith called on Wilkie in 2004 to renew the long-neglected landscape at Boughton, the designer turned to this ancient legend and to the primordial land forms that had become his trademark. A man of wide-ranging experience and education, Wilkie grew up first on the edge of the Malaysian jungle, then in the Middle East where his father was posted. There he had the opportunity to see the ancient ziggurats and to contemplate how early civilizations left their mark on the earth. His family returned to England and settled in Hampshire where again he lived with earthworks including ancient stone circles, barrows, tumuli, burial mounds, henge, trough and furrow, ramparts, and even redoubts.

Wilkie credits the computer with the precision of the cuts made in the earth to realize his design at Boughton House.

At Oxford he read modern history. Then, as he reports, at age twenty-one he learned there is a profession of landscape architecture. He was ecstatic for “I could hardly believe that everything I loved could be wrapped in one profession: people, land, biology and drawing.” He went to the University of California Berkeley to study for his now-chosen career. As a student and then young professional he found himself returning to mankind’s ancient myths and landforms, seeing in them a yearning for meaning and spiritual expression.

At Boughton House Wilkie was presented with a wonderful old landform, conceived and built in the 1720s. A truncated pyramid twenty-three feet high, it was intended by the eighteenth-century owners of Boughton House as the foundation for a family mausoleum similar to that at Castle Howard, but the mausoleum was never constructed. The designer was Charles Bridgeman, a leading landscape architect of the time who also worked at Castle Howard, Stowe, and other eighteenth-century English estates. Bridgeman’s pyramid at Boughton was part of a geometric design. Like Studley Royal, it retains the formal lines of the older French Baroque style.

A rill delineating the golden spiral begins on the far side of Wilkie’s reflecting pool, each successive golden rectangle itself divided by the golden mean until the golden spiral emerges.

Pointing to the pyramid, Lord Dalkeith asked of Wilkie, “So, what would you do with this?” Without hesitation, Wilkie suggested creating a mirror image, replicating the lines of the eighteenth-century pyramid base but in reverse, so that the old mound rises as Mount Olympus, and his sunken ziggurat points to the earth’s center. Like Vignola at the Villa Lante, William Kent at Rousham, and Henry Hoare at Stourhead, Wilkie told a classic and classical story with his plan.

As he began the landscape design, Wilkie discovered the brilliance of Bridgeman’s geometry. He looked out over the canals, avenues, and grass terraces created between 1685 and 1725 and saw the lines and proportions extolled by the Greeks and used brilliantly by André Le Nôtre in his French Baroque gardens. In what he calls “the axial rhythm” of squares and rectangles, Wilkie recognized the golden rectangle, the “harmonic proportions” created by each division of the rectangle through the imposition of a square within it.

Wilkie created on the ground plane adjacent to the mound and his inversion of it a golden rectangle with squares interposed. It would remind the viewer of human civilization between the heights of Mount Olympus and the depths of the world beneath. In particular it would celebrate mankind’s knowledge and accomplishments: the golden ratio or golden mean, the great myths of classical Greece, and Boughton’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century roots. Today musical performances are held in this remarkable setting as if Orpheus has always resided in this place where Wilkie’s “temple” expresses the musician’s genius.

Kim Wilkie says of his work: “Each place has its own special character and identity—a continuous conversation between the physical form and the lives lived and shaped within it. As a landscape architect, I try to understand the memories and associations embedded in a place and the natural flows of people, land, water, and climate.”

So also have the designers of these one hundred gardens drawn upon their time and place, their cultural roots, their beliefs and values—the intersection of their life history and the historical moment. And so it will be in the future as a new generation of landscape designers takes up their art, revering the archetype and discovering the genii of the place and of themselves.