Until the late-nineteenth century, Corleck Hill, in the Co. Cavan townland of Drumeague, was the site of a Lughnasa festival held on the first Sunday of August. Lughnasa was one of the great quarterly feasts of the old Irish year, and it also retained millennia-old memories of the Celtic god Lugh. The Lughnasa festival, which continues to be celebrated in Ireland to this day, ran over three days, echoing the idea of a tripartite deity. (It is now celebrated on the Sunday closest to 1 August, with the most celebrated event being the annual pilgrimage to the top of Croagh Patrick in Co. Mayo).

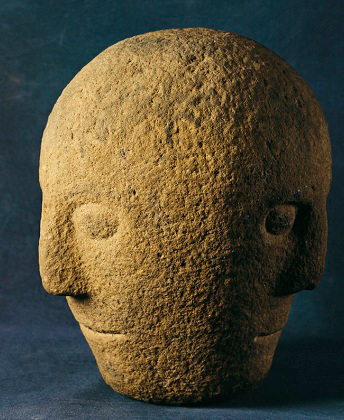

This potently enigmatic stone head was found c. 1855 near Corleck Hill. Carved into a 32cm-high piece of rounded sandstone are three broadly similar faces, all with narrow mouths, bossed eyes and remote, implacable expressions. A small hole in the base of the head suggests that it was secured to some kind of pedestal. One of the mouths also has a small circular hole, a feature that links it to several carved heads from Yorkshire. This link to Roman Britain reminds us that Ireland is, at this time, on the cusp of the Roman world. Even if the Corleck Head represents a new variant in religious practice, however, it also speaks to us of an astonishing continuity.

The head is often taken to represent an ‘all-knowing god’, who can see all dimensions of reality, but its three faces also link us back to much older traditions of the three-natured goddess. The ‘power of three’ is an important theme of Celtic art and is represented in the common symbol of the triskel, or triskelion: three interlocked spirals. It relates to the triple nature of the great goddess, the Morrígan: sovereignty, fertility and death; it is also common in Romano-British art, through the figures of the Matronae, the three ancestral mothers, representing strength, power and fertility. The Corleck Head, which is neither obviously male nor female, and which can be seen to unite old Irish and new Romano-British cults, touches all of these nerves.

In the context of the Lughnasa festival, the head may represent the old god Crum Dubh, who was buried for three days with only his head above ground, so that the young Lugh could temporarily take his place. Máire MacNeill, in her classic The Festival of Lughnasa, suggests that there was a custom of bringing a stone head from a nearby sanctuary and placing it on the top of the hill for the duration of the festival. The head looking in different directions may be…looking propitiously on the ripening corn-plots.That something of this ritual survived in modern Ireland (and into Brian Friel’s play ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’) is spine-tingling but not entirely illogical. The Corleck Head may represent a late expression of pre-Christian religion, but it also points forward to a religion that was beginning to spread from the Mediterranean—the one with three persons in one God.