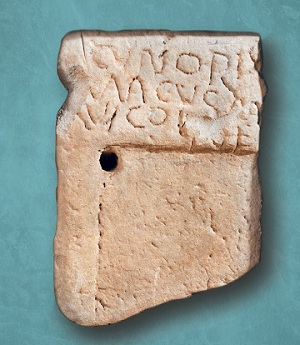

It is a broken gravestone, with a crude inscription: cvnorix macvsma [q]vico[l]i[n]e. The slab, found in 1967, had probably been re-used from someone else’s burial. Yet it is resonant of the way Irish invaders and raiders took advantage of the collapse of Roman Britain.

The slab was found in Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury in the western English county of Shropshire. This village was once Viroconium, the fourth-largest city in Roman Britain, a thriving hub of 5,000 people—about the same size as Pompeii. After the Roman legions were withdrawn from Britain, in 410, even places as far inland as Viroconium became vulnerable to attack from Irish raiders. The significance of this gravestone is that the inscription is in a partly Latinised version of the Irish language. It means ‘Hound-king, son of the tribe of Holly’. Cunorix was Irish, and the existence of the stone suggests that he had become a powerful figure in this part of England.

From the fourth century ad the Romans were building forts on the west coast of Britain (at Holyhead and Cardiff) to defend against the Irish raiders they called ‘Scotti’ (the name survives as Scotland). We know from the Roman writer Ammianus that diplomatic relations had been established with the Scotti but that in ad 360 the breaking of a treaty led to devastating raids from both Ireland and Scotland. The ability to mount major seaborne raids suggests a resurgence of wealth in Ireland, connected to the expansion of agriculture and the building of huge numbers of stone ring-forts. As Roman power collapsed entirely, Irish raiders were followed to Britain by Irish settlers. The most important colony was at Dyfed in southwest Wales, but Argyll in western Scotland, the Isle of Man and parts of southwest England were also colonised.

This expansionary drive had huge consequences in Ireland. The Romans had done deals with, and helped to keep in place, the old kingships in Ireland. The new money that both funded and resulted from attacks on Britain, however, allowed the formation of numerous small tribal units, or túatha. ‘There were’, says Conor Newman of NUI Galway, ‘new kids on the block in these centuries. Before the fourth or fifth centuries you have five great royal sites. It is not coincidental that Roman material has turned up at all of those sites. Afterwards, the country is fragmented into 150 smaller túatha. Something pretty radical has happened. I think it is the impact of the collapse of the Roman Empire on Ireland. Britain becomes an open cash register for Irish raiders. Things are being robbed—and so are people. The status quo is undermined’.

For the existing British population, much of this was deeply unpleasant, but the colonisations did result in much closer ties between the two islands and a stronger British influence on Irish culture. Ironically, one long-term result was the spread from Britain to Ireland of what had become the official Roman religion.