Ego Patricius, peccator rusticissimus et minimus omnium fidelium et contemptibilis sum apud plurimos… ‘My name is Patrick. I am a sinner, a simple country person, and the least of all believers. I am looked down upon by many…’

These artfully humble words mark three immense moments in the development of Irish culture. First, along with Patrick’s Letter to Coroticus, it is the oldest surviving piece of prose writing done in Ireland, and so signals one immense change: the arrival of literacy. Second, Patrick is the first person in Ireland who can, through these texts, be positively identified as an individual with a known life story. This, in other words, is the moment when prehistory ends and Irish history begins. Third, of course, Patrick’s ‘Confession’ speaks to us of one of the most paradoxical but profound developments in that Irish history. On the one hand, it is a dramatic narrative of the collapse of the Roman Empire. As he relates it, Patrick, son of a noble Romano-British family, is kidnapped at the age of sixteen and enslaved as a herdsman by Irish raiders who no longer fear the might of Rome. On the other, just as Roman power is vanishing, Patrick brings it to Ireland in another form: Christianity.

Patrick was not the first Christian missionary to Ireland. Palladius, probably from Auxerre, in France, was sent in 431 as the first bishop to ‘the Irish believing in Christ’—a pre-existing Irish Christian community. Some of these early Irish Christians may have been, like Patrick himself, slaves captured in Britain.

Patrick, however, as he says in the Confessio, preached the Gospel ‘unto those parts beyond which there lives nobody’. Tradition places the hub of his mission in Armagh. Patrick claims that in Ireland, where they never had any knowledge of God but, always, until now, cherished idols and unclean things, they are lately become a people of the Lord, and are called children of God; the sons of the Irish and the daughters of the chieftains are to be seen as monks and virgins of Christ.

This overstates the speed of the movement from the old religion to the new, but it reflects the reality that Patrick played a key role in the spread of Irish Christianity.

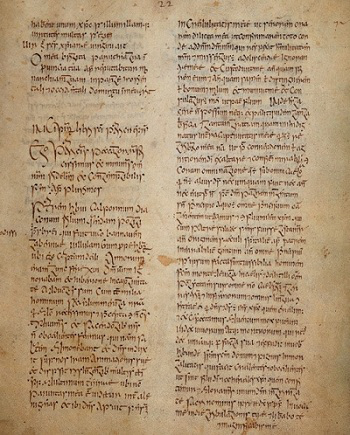

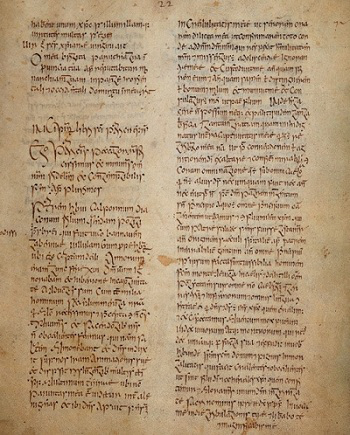

Pictured is the earliest surviving manuscript copy, made around 807 by the scribe Ferdomnach in Armagh. (Its opening words appear on folio 22r of the Book of Armagh, which is displayed with the Book of Kells at Trinity College Dublin.) It leaves out those parts of the ‘confession’ in which Patrick mentions his own failures and weaknesses: for the later monks who were involved in establishing his cult, it was important to show him as a powerful worker of wonders. Most probably, while he was alive, it was his humility and simplicity that made Patrick so attractive and persuasive.