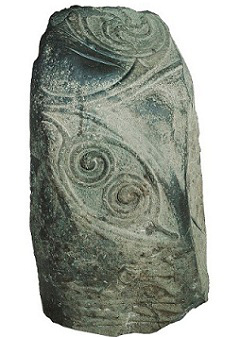

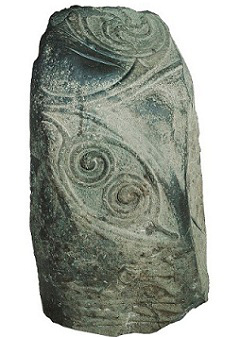

When a castle at the Hill of Mullaghmast in south Kildare was being demolished, this limestone boulder was found being re-used as a lintel. The spiral carvings, which are close in style to those found on metal dress-pins and brooches of the period, date it to the sixth century ad, after the mission of St Patrick. What is intriguing, however, is that its symbolism reminds us that in Ireland the arrival of Christianity did not mark a sudden break with the past. Instead, the stone speaks of a remarkable continuity of one of the so-called Celtic rituals that resonates even today: the sword in the stone.

The idea of the true king being the one who can pull a sword from a stone is central to the British legends of King Arthur. Conor Newman of NUI Galway has noted that many sacred stones that functioned as ‘icons of tribal and cultural identity’ have straight, narrow grooves on their surfaces. These marks have generally been dismissed as results of vandalism or ploughing. But Newman has pointed out that they occur far too often and are far too regular for this to be the case.

The Mullaghmast Stone is one such stone. It almost certainly stood at where the Uí Dúnlainge kings of Leinster were initiated. In itself, it is notable that such an important ritual object has no Christian symbolism. ‘There is little doubt that this is the inaugural stone of the Uí Dúnlainge’, says Newman, ‘and there’s nothing in the ornamentation that you could describe as Christian’. This does not necessarily mean that those who first used the stone were clinging to the old religion, but it does show that in Ireland, Christianity was often another layer on top of older traditions that survived and thrived. Rituals of kingship in particular retained their broad shape for another thousand years after the emergence of Christianity; the idea of the ‘sword in the stone’ seems to have lasted at least from the fifth or sixth centuries to the twelfth.

The Mullaghmast Stone has four blade marks on the left-hand side and two very deep ones on the top. The new king, it seems, would have struck or sharpened his sword against the stone as a key part of the inauguration ritual. The persistence of such rituals may be rooted in the paradox that emerging local chieftains, with new wealth gained from the exploitation of the collapse of Roman Britain, needed to disguise the novelty of their power. These arrivistes, says Newman, ‘still have to legitimate their power. If you are an arriviste, the first thing you do is buy a house and fill it with antiques. There is a very keen awareness of the rituals surrounding that moment of taking your place in history’. These rituals may have been self-consciously archaic, used by upstarts to claim the authority of antiquity.