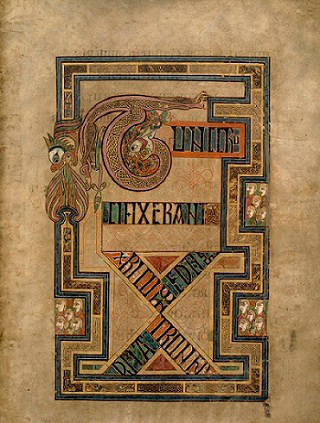

It has been called the Irish equivalent of the Sistine Chapel, and the analogy is not ridiculous. The Book of Kells is not merely the greatest work of Irish visual art, it belongs among the great creations of Western art.

One big difference between the Book of Kells and the Sistine Chapel, however, is that the manuscript is also funny and playful and combines its grand religious vision with a homely humanity. Everywhere there are touches of comedy: a letter extended to form a monk’s tonsure, a word broken in two by the paw of a cat. This is not to say that the task of making the book was anything but serious. It required the skin of 185 calves to make the vellum pages. The range of pigments used for its colours—orpiment, vermilion, verdigris, woad and, perhaps, folium—is far greater than that of other contemporary books. There may have been one guiding visionary leading the team of monks, as it is clear that on many pages the script and the images were created by the same hand.

There have long been arguments about where the book was made, with suggestions ranging from Spain to (more plausibly) the great monastery at Lindisfarne, in Northumbria. The consensus is that it was probably made on the island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland, whose heavily Irish monastery was founded by St Colmcille in 563. It may well have been intended to honour his memory: from early on it was known as ‘the great book of Columcille’. Iona was raided by Vikings in 802 and 806, and many of its monks retreated to a new base at Kells. The probability is that they brought at least the bulk of the book with them: some subsequent work on it may have been done in this new monastery in Co. Meath.

Whatever its precise history, the book can be securely placed within Irish culture. The contorted animals, highly stylised humans and fabulously ornate initial lettering are rooted in the La Tène tradition of ‘Celtic’ art that by the ninth century had been alive in Ireland for 1,000 years. Many of the animal and bird images are comparable to those created by the great Irish metalworkers, but, in a way that is also typically Irish, the book is fed by many cultural streams, from Pictish sculpture in Scotland to Visigothic and Carolingian design in Spain and France, and even to the Coptic art of the North African church.

It seems that the monks who created the book paid more attention to the sumptuous visual art that decorates it than to the sacred text: there are numerous spelling mistakes, and at one point a whole page is repeated. This suggests that the book was never intended for practical use in readings at Mass, but rather was regarded from the beginning as an extraordinary object. The book’s richness lies in what art historian Roger Stalley has called: the constant humour and vitality of the ornament, the freshness of the pigments, the unwavering beauty of the script and the haunting ambiguity of the religious imagery. Its genius is that it is sacred but never solemn. The vividness, vibrancy and constant, joyful invention make it seem almost a living thing.