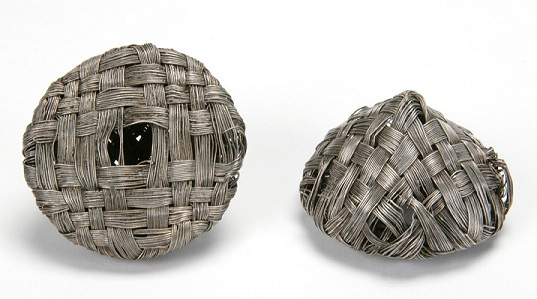

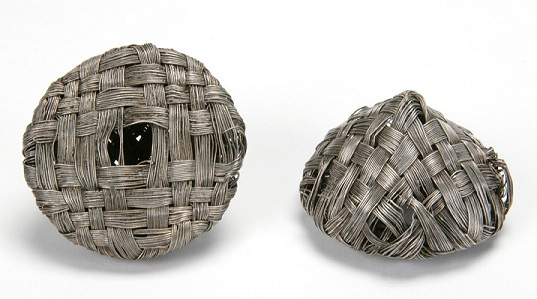

The slave chain is at the brutal end of the spectrum of Viking Ireland. This gorgeous cone of woven silver wire is, physically and symbolically, at the other extreme. It sits in the palm of the hand as lightly as a confection of spun sugar. It speaks of delicacy and delight, of complex conception and marvellous execution. It is hard to think of anything further removed from the idea of brute force.

‘When I look at this’, says Andy Halpin of the National Museum, ‘the first question that comes to my mind is, How do you make it? From a technological point of view, it is an extraordinary thing’. There are three separate interwoven bands of silver, each composed of between fifteen and eighteen wires. Yet, Halpin says, it is very hard to find where any of these wires ends. The visual effect is that of a single thread turning endlessly around itself. There are traces of some kind of organic material inside the cone, possibly a wax shape around which the wires were woven. The visual imagination and the physical deftness required to do so are of the highest order.

This cone is one of the largest of a group of eighteen found in 1999 in the limestone cave at Dunmore, just north of Kilkenny city. The cave was well-known in early mediaeval Ireland, and the annals refer to a great slaughter perpetrated there around 930. The cones were found with coins that indicate a later date for their deposition—about 970.

The larger cones like the one pictured are unique objects, but the smaller ones in the hoard have parallels in Viking burials on the Isle of Man and Iceland. What we may have, then, is a development in Ireland of a general Norse form. The possibility that the cones were made in Dublin points to a very high level of distinctive craftsmanship in the new town by the mid-tenth century.

What were the cones for? A border of silver wire to which they seem originally to have been attached was found with the cones. More exciting was a small, unpromising-looking remnant of textile that turned out to be very fine silk. It seems that this was an elaborate silk garment with a silver wire border and cones that functioned either as tassels or as buttons. The silk itself may have been more valuable than all the silver put together. It had come, almost certainly, from either the Byzantine empire or the Arab world. The dye used to colour it was either red or purple. If it were the latter, the dress was truly amazing: purple dye was breathtakingly expensive. Either way, the woman who originally wore this garment must have made a dazzling spectacle. For the display of female wealth and status in tenth-century Western Europe, glamour does not get much more fabulous than this.

Who this woman was is as mysterious as the presence of this extraordinary example of Viking power-dressing in Co. Kilkenny. All we know is that someone had a garment worth a king’s ransom, shoved it in a crack in a cave, perhaps in a moment of panic, and never came back for it.