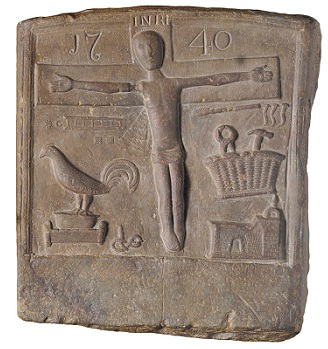

In 1950, during rebuilding works on an old house in Summerhill in Co. Meath, this rough piece of sandstone was found behind a blocked doorway. It had been in a window recess of a secret, sealed-up chamber. On its face is a carving of the Crucifixion, with the symbols of Christ’s Passion and the date 1740. The imagery is vernacular and earthy: the rope used to tie Jesus’s hands, the cock that crowed to mark his betrayals by Judas and Peter, the dice thrown by the Roman soldiers, the hammer and pincers used in the Crucifixion and the temple of Jerusalem. The shape of the cross suggests it was based on those sold to pilgrims at Lough Derg.

The stone was clearly used for secret Catholic worship, and its date coincides with one of the first attempts by the state, in 1739–40, to enforce laws penalising Catholicism. It speaks both to the severity of attempts to repress Catholicism and to their failure. Irish Jacobite resistance, and hopes for a reversal of the transfer of lands from Catholics to Protestants, ended with the Treaty of Limerick in 1691, which seemed to secure Catholics’ existing property and religious rights. It promised the same level of tolerance

as they did enjoy in the reign of King Charles the second: their majesties...will endeavour to procure the said Roman Catholics such farther security...as may preserve them from any disturbance upon the account of their said religion.

Catholic members of the landed gentry who swore allegiance to the new regime could keep their lands.The Irish parliament refused to comply. Instead, a series of penal laws against Catholics was put in place. The Protestant ascendancy did not regard itself as secure: France remained a threat, as did the papacy’s continuing support for the Stuart cause. Some former Jacobites remained active as ‘rapparee’ or ‘tory’ outlaws. In 1695, the parliament passed laws prohibiting Catholics from bearing arms without a licence, owning militarily useful horses or travelling to the Continent to be educated.

Gradually, concerns with security became a more nakedly religious project of penalising Catholicism. Laws ‘for the suppression of Popery’ passed in 1697 and 1703 required bishops, deans, vicars general and friars to leave the country and remaining clergy to register with the authorities; other laws excluded Catholics from parliament, corporations, the army and navy, the legal profession and civic offices; and prevented Catholics from buying land, leasing it for more than 31 years or running schools.

The laws helped to underpin Protestant domination of landholding. The Catholic share of the land fell from 14 per cent in 1702 to 5 per cent by 1776 (many landowning families were converts or crypto-Catholics). In general, the laws were a failure. The majority of the population remained Catholic, and sporadic persecution failed to stop the training of Irish priests in continental seminaries. Catholic worship continued, albeit, as this stone shows, discreetly. The penal laws were evaded, flouted or, if necessary, endured. They did not ‘suppress Popery’.