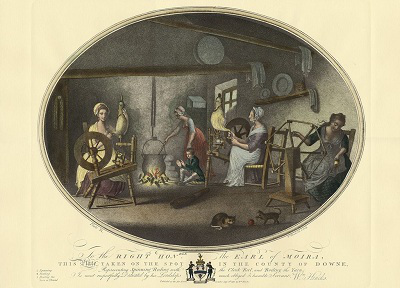

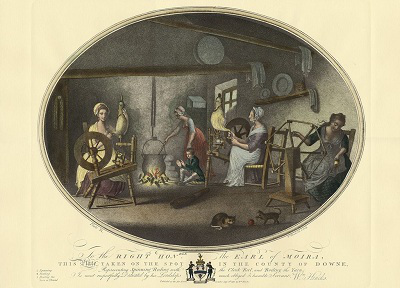

This engraving, one of a set of twelve by Irish artist William Hincks, is a rare artefact: it acknowledges the work of women. It is, as the title explains, a view ‘taken on the spot in the County of Downe, Representing Spinning, Reeling with the Clock reel, and Boiling the Yarn’. The work was hard, but the relative prosperity of the cottage depicted in the engraving hints at the enormous impact the linen trade had on Irish standards of living in the eighteenth century. Irish people had been growing flax and making linen since the Bronze Age. With Ireland largely pacified in the early-eighteenth century, the authorities promoted the development of linen as the primary Irish industry. The wool industry was discouraged to avoid competition with England, and linen was an unthreatening substitute.

The Linen Board was formed with public money in Dublin in 1711 to regulate the growing industry. In the second half of the century production expanded dramatically, and by 1800 linen exports had risen to between 35 million and 40 million yards. Early linen production was not industrialised. It centred on farm-family units, with the whole household involved in planting and harvesting the flax, the women and girls spinning it into yarn and the men weaving the yarn into cloth.

Linen had a particularly dramatic effect on the economy of Ulster, transforming a hitherto poor province into the most prosperous in Ireland. Initially, the trade was centred on the Linen Hall, which opened on Dublin’s north side in 1728; the Ulster origins of much of the cloth was acknowledged in the surrounding street names: Coleraine, Lurgan, Lisburn. Gradually, however, Ulster traders took control of the export business and Belfast Linen Hall opened in 1783. In the ‘linen triangle’ between Lisburn, Dungannon and Armagh in particular linen drapers formed a new entrepreneurial nexus, typically Presbyterian and often open to radical ideas, especially during and after the American Revolution.

Linen transformed Ulster in other ways too. Hunger for land to grow flax led to the destruction of the last of the great Ulster forests that had terrified Tudor armies: the last wolf in the Sperrin Mountains was killed in the 1760s. The population rose rapidly: between 1753 and 1791 the number of households paying hearth tax in Ulster doubled. Market and estate towns such as Banbridge, Downpatrick and Newtownards were redeveloped. This rapid change produced new social tensions, including militant protests in 1771–2 by groups called the Hearts of Oak and Hearts of Steel, enraged by bad harvests, taxes and rent rises. Emigration to Colonial America peaked in the 1770s; in the 1780s sectarian tensions rose, especially in Co. Armagh, now the most populous county in Ireland, where the Protestant Peep O’Day Boys and the Catholic Defenders engaged in low-level warfare. These tensions were fuelled, ironically, by the very success of the linen trade, as Catholic and Protestant weavers competed for business.