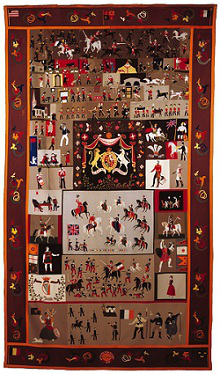

This remarkable table cloth, measuring eight feet by four and showing 250 different figures in 31 panels of inlaid felt patchwork, is the work of one man over 20 years. Stephen Stokes was born in Plymouth in 1802 and enlisted in the army as a boy. In 1819 he entered the 63rd Regiment, then stationed in Ireland, transferring to the 1st Royal Dragoons in 1826. On leaving the army in 1836 he joined the newly formed Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), initially as a sergeant. He retired as inspector of mounted police in 1855 and became superintendent of the Turkish baths in Lincoln Place. He died in 1900 at the age of 98.

Stokes seems to have been self-taught and presumably began his project to stave off the boredom of barracks life. His patchwork evolved into a panorama of political, military and even cultural affairs. At the centre are Queen Victoria and Prince Albert reviewing the troops, the royal coat of arms and a vivid depiction of the capture of a French standard at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 by the 1st Royal Dragoons, presumably described to Stokes by colleagues in the regiment who were veterans of that epic clash.

The real fascination of the patchwork, though, lies in its scenes from ordinary military life and from very different aspects of Irish affairs. Running across the width of the cloth, there is a funeral procession for a dead dragoon. Another sequence shows soldiers being punished for breaches of discipline by having to break rocks or march with a heavy wheelbarrow, all supervised by a provost marshal with an enormous pipe. A later panel shows a member of the DMP mounting a white horse—possibly Stokes himself.

There are contrasting scenes from Irish life. One is of Donnybrook fair, a proverbially riotous annual gathering south of Dublin. Another is the visit of the celebrated ‘Swedish nightingale’, Jenny Lind, to the Theatre Royal in Dublin in 1847. For the following year, however, Stokes depicts ‘The Irish Constabulary and the Boys of Ballingarry’, representing the abortive 1848 rebellion of the Young Irelanders. This group, a violent breakaway from the mainstream repeal movement, had serious ambitions and approached the French revolutionary government. After two of its leaders, John Mitchel and Charles Gavan Duffy, were arrested, about 100 members engaged in a desultory skirmish with 40 policemen in Co. Tipperary, an engagement derisively known as ‘the battle of the Widow McCormack’s cabbage-patch’. William Smith O’Brien, Terence Bellew McManus, Thomas Francis Meagher and Patrick O’Donohue were sentenced to death but were instead transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1849.

Stokes’s depiction of the ‘battle’ is striking for two reasons: he shows the rebels as giants compared to the diminutive policemen; and he gives prominence to a very early depiction of the rebels’ flag: a tricolour of green, white and orange. Brought from Paris, where it was displayed to show the Young Irelanders’ affinity for the French revolution, it symbolised, said Meagher, the hope that ‘beneath its folds the hands of the Irish Catholic and the Irish Protestant may be clasped in generous and heroic brotherhood’—an aspiration yet to be fulfilled.