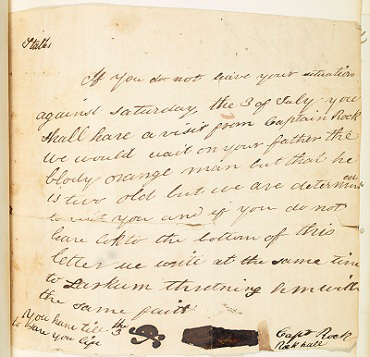

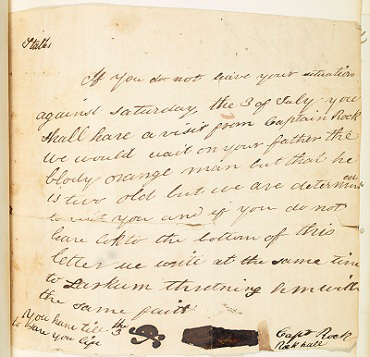

One of the great hidden objects of Irish history is the threatening letter. For a burgeoning population of very poor tenants, Daniel O’Connell’s campaigns for Catholic emancipation and repeal of the Act of Union had less urgency than matters that bore on their immediate survival: rent, land tenure and the tithes that were extorted from Catholics to pay Church of Ireland clergymen. For much of the nineteenth century, the most violent resistance of the anonymous poor was personified in a single, mythical figure, Captain Rock, whose name was appended to thousands of threatening letters, like this one sent to Thomas Larcom, the chief surveyor of Ireland, in 1842.

Secret, oath-bound societies, generally known as Ribbonmen, survived the repression of the 1798 rising. Liberal republicanism was largely eclipsed in their ideology by a millenarian and sectarian fervour crystallised in an exotic word: Pastorini, the pen name of Bishop Charles Walmesley, whose reading of the Book of Revelation led him to predict in the 1770s that God’s wrath would punish Protestant heretics in 50 years time. During an outbreak of famine and fever in 1817, condensed versions of Pastorini’s prophecies began to circulate among rural Irish Catholics. The idea that Protestants would be wiped out by 1825 gained a powerful hold.

A Co. Limerick blacksmith called Patrick Dillane, distinguished in the art of throwing rocks, was ‘christened Captain Rock by a schoolmaster…by pouring a glass of wine on his head’. The name became a code for the sense that, as a Rockite puts it in a story by William Carleton, ‘we’ll have our own agin’.

Rockism swept through Munster and south Leinster between 1821 and 1824, with savagely violent attacks on landlords, agents, tithe collectors, and middlemen. More than 1000 people were murdered, mutilated or badly beaten. The millenarian fervour was evident in threatening letters containing phrases like the exuberantly apocalyptic ‘Vesuvius or Etna never sent forth such crackling flames as some parts of Donoughmore will shortly emit’. (The letters were not at times without a certain grotesque humour: ‘In compassion to your human weaknesses and in consideration of the enormous weight of your corpulent fraim [sic], I mean to rid you of these inconveniences by a decapitation’.)

At its height in North Cork, Rockism could bring thousands of men and women into open insurrectionary action against troops and yeomanry. The Rockites won no military victories, but their campaign of arson and murder did succeed in cowing local magistrates, stopping the collection of tithes and lowering rents. The intimidation of witnesses and ‘informers’ created a period of virtual legal immunity.

It took large-scale military occupations, mass hangings, transportations and the introduction of the brutal Insurrection Act, suspending civil liberties (most of those sentenced were accused of nothing more than breaking the curfew), to end Captain Rock’s three-year reign of terror. Even then, the memory of the violence was evoked in subsequent decades, as this letter shows, to threaten unpopular landlords or officials with a name that remained charged with ferocity.