Stanzi—Thursday—Another Frog Dissection

1. Place frog in tray, ventral side up.

2. With forceps, lift the skin of the lower abdomen. Cut with scissors.

3. Slide scissors into the opening and cut to below the lower jaw.

4. Cut the sides just posterior to the forelimbs and anterior to the hind limbs.

This is my seventh frog dissection this year. Mr. Bio lets me help with the freshmen if they’re dissecting. I am the best frog surgeon he knows. That’s our joke. I bet he’d make me a name tag that says BEST FROG SURGEON if he could, but he’s not very artistic. I’m his assistant, and I help hand out the forceps and scalpels while the students get into their lab coats and put on their goggles. I can’t actually hand out the frogs, though, because I’m always surprised by how dead they are.

Gray-green.

Bred so we could cut them open and find their livers and draw them for points in a notebook.

Mr. Bio told me in ninth grade, “You’re going to make an excellent doctor one day.”

“That’s the plan,” I said.

“It’s a good plan.”

“I want to help people,” I said.

“Good.”

“I know I can’t help everybody, but even if I can help just one person, you know?”

“Yep,” he said.

“I’m thinking about going into the army,” I said.

Mr. Bio made a horrible face. “Why?”

“Did you ever watch M*A*S*H?” I answered. M*A*S*H is a late-twentieth-century TV show about a mobile army surgical hospital unit during the Korean War. It reruns on cable a lot. The main character is Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce. He’s a surgeon from Maine.

“Of course,” Mr. Bio said. “I grew up with M*A*S*H.”

“That’s why,” I said. I didn’t tell him Hawkeye Pierce is my mother. No one would understand that. Hawkeye Pierce was a man. A fictional man. Most people would think he couldn’t be anyone’s mother. Except he’s mine. He puts me to bed every night. He makes my dinner. He teaches me about the world and he’s always honest.

Mr. Bio put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You should stay away from that recruiter.”

“It wasn’t the recruiter,” I said.

“Well,” he said. “There are better ways to pay off med school loans. We’ll talk about it once you get closer to graduating.”

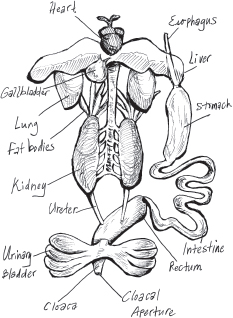

We did. Talk about it. I am now sixty days from graduating. Mama and Pop don’t think going into medicine will be good for me. They think I should be a forest ranger. I have no idea why, especially on days like today when my scalpel knows just where to go. Especially on days like today when I don’t even have to refer to the drawing to locate the heart, the stomach, the liver, the urinary bladder.

Mama tells me that being a forest ranger will be quiet.

She says, “Trees help us breathe, you know.”

This morning, the school administration got a letter. The letter claimed to be from a student who was going to blow us all up before testing week. Nobody is supposed to know this, but I know. You want to know how I know, but I can’t tell you that yet.

The point is: Somebody sent a letter and nobody knows who it was.

But I might.

He or she could be here with us today, scalpel in hand, and from here behind your plastic goggles you’d never know he or she could write that and send it.

He or she is not what you think.

I don’t think they ever are.