Stanzi—Wednesday—We’re Very Lucky

AP physics class will be held under the black walnut tree from now on. The spring weather has everyone in T-shirts and better emotional disposition. “At least this way, we can get something done,” Gustav says. “At least this way, we aren’t always in a state of drill. In. Out. In. Out. In. Out. Sniffed by dogs.”

AP bio students make a circle next to a nearby holly bush and talk about our ancestors’ hair and eye color. I didn’t have time this morning to ask Mama and Pop about the family medical history, but I’m pretty sure they would have lied to me about it anyway.

Mr. Bio asks me which traits in my family are most common and I say, “Brown eyes and dark brown hair.”

He nods and moves on to the other students. I don’t listen. Instead, I watch a bird deep in the holly bush, calling out. Surrounded by us. Trapped. Calling out for help, perhaps. Calling out in fear. Calling out about spring.

Good-bye, cold and snow!

Good-bye, hunger!

I look over to the black walnut tree. Gustav is talking to Lansdale Cruise again. Her hair hangs down to below her knees, and she fiddles with it as if it’s a magician’s medallion. She swings it and hypnotizes everyone. All of us, under a spell.

Lansdale has a reputation. When she talks about sex, we know she’s never had it. When she gets letters from the bush man, we know she lied somehow to attain them. She is like Pinocchio except her hair grows, not her nose. A mixed-up fairy tale. Pinocchapunzel. I guess she’s beautiful if you think beautiful people lie that much.

I note that Gustav looks uncomfortable talking to Lansdale. He looks past her. He looks at me. I can see inside his brain and this is what it looks like:

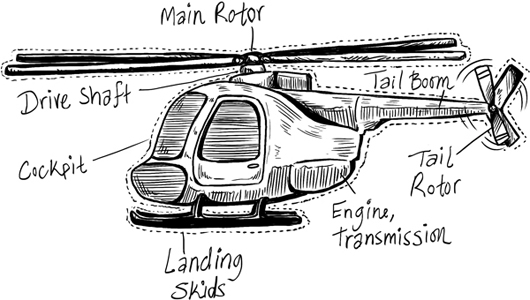

I asked him once where he’s going to go in the helicopter. He told me he couldn’t tell me yet, but I knew from his eyes that there is a destination. When I see him trying to talk to Lansdale, I wonder if he pictures the place in his head every day as he builds. I wonder if it’s so far away that I might never see him again.

When AP-bio-at-the-holly-bush is over, I’m approached by the principal. She asks me to follow her back into the building. She sits me in a blue upholstered chair in her cluttered wood-paneled office and asks me to wait until someone else arrives.

I guess who someone else could be. My parents, the guidance counselor, Mr. Bio, Gustav, China, Lansdale?

I guess maybe she’s found out about the man in the bush. Maybe she wants me to testify against him, though he’s never done anything wrong to me. Then I guess I’m being too negative, and since it’s spring, maybe I won a scholarship or something. I applied for two.

The principal returns with the superintendent.

I smile at them both as they close the door and sit down. They ask me, “Do you know who’s sending these bomb threats?”

I answer, “Yes and no.”

They say, “Don’t be coy.”

I say, “I’m not being coy. I don’t want to speculate.”

The principal says, “Didn’t you dissect a frog last week?”

I say, “Yes. Many of us did.”

The superintendent opens a box. It contains about five frog livers, dehydrated. It also contains lug nuts, a condom still in its wrapper, a small bottle of red food coloring, a lock of Lansdale’s long, lying hair, and a hinge from a saxophone key.

I don’t know what to say, so I say, “That’s an interesting boxful of things.”

She says, holding up a frog’s liver, “Do you know what this is?”

I say, “Did you know that the liver is the only organ that can regenerate itself? Isn’t that amazing?”

The principal frowns. “Are those your frog livers?”

I say, “I don’t have any frog livers, to my knowledge.”

We all look at each other. The superintendent looks tired. She has black rings around her eyes. I wonder if she’s slept since the bomb threats started.

She says, “Are you sure you don’t know?”

I say, “I’m sure that I’m not sure. But I can keep trying to figure it out for you. I’ve been investigating since the first one. I’m close, but I can’t be certain.”

She nods.

“Did you get any fingerprints from the bomb-threat boxes?” I ask. “Or the letters?”

“No.”

“Did you get traceable IP addresses from the bomb-threat e-mails?”

“No.”

“Could the police trace the bomb-threat phone calls to any single number?”

“No.”

“Looks like we are dealing with a very smart person,” I say.

They stare at me.

Maybe they think I’m smart enough to do all these things.

I’m flattered.

That night at home, Mama is there in place of the Gone to bed note because Pop has a late eye doctor appointment. While she takes a nap before dinner, I watch an episode of M*A*S*H where an unexploded bomb lands in the middle of the 4077th hospital compound. Hawkeye Pierce has to try to defuse it. It’s high drama, but in the end it’s just a bunch of funny flyers about the Army/Navy football game that explode into the sky.

A joke bomb. Just like ours.

I wonder what our joke-bomb letters would say.

English 12.……………A

Calculus………………B+

AP Biology……………A

AP World History..……B+

Physical Education.……C-

Dear Mr. & Mrs. ____________, Your son/daughter has been selected to serve as a square of human confetti in the science wing one day this year. Please sign this permission slip and return by tomorrow. Our condolences.

While we make enchiladas and line them up in the glass dish, Mama asks me how the drill was today. “Nice day to be outside,” she says. “Spring has definitely sprung.”

“I watched a bird in a holly bush,” I say.

“What kind of bird?” she asks.

“Eremophila alpestris,” I say.

She pretends I’ve said nothing.

“A horned lark,” I say.

“Well, that’s nice,” she says, but she’s already fastened into the TV news playing on the kitchen set. Something about a man who kept teenaged girls locked up in his basement for ten years. She’s swallowed by the story, even though she knows all about it already. They’ve been looping it for days.

“The superintendent thinks I’m the one sending the bomb threats,” I say.

“That’s ridiculous,” she says, not taking her eyes off the screen. “Of course it’s not you.”

“Of course,” I say. “Or it could be. Nobody knows,” I add, just to see if she’s listening.

“How’s Gustav?” she asks.

“I’m going to see him after dinner,” I say. “But I have to finish my bio worksheet first. Can you tell me if we have any history of cancer, heart disease, or autoimmune disease in our family, and if so, who had it?”

She lowers her brow to think, then cocks her head toward me and claims we are a 100% perfectly healthy family that has never had any diseases.

“If more people were like us, then there’d be no need for health insurance!” she says. “If more people were as lucky as us, then the world wouldn’t be so crazy!” she says.

“Yes,” I say. “We’re very lucky.”

When I fill in the bio paper, I write that my maternal grandmother had cancer and my paternal grandmother has high blood pressure. I say that Pop’s father is fighting dementia right now and that Mama’s father has struggled with multiple sclerosis for the last five years.

When Pop gets home, we eat dinner together. It’s a welcome break from the TV dinners I feed myself most nights. I tell Mama and Pop I can’t seem to write my poem for English class. I tell them I still haven’t heard back about the scholarships. I tell them I got an A on my statistics project.

Mama says, still watching the set with the sound muted, “Isn’t it awful what that man did to those girls?”