The Battle of the Grand Coteau

In 1849 about three hundred Métis relocated to Pembina, adding to the existing population of five hundred hunters and their families. The Pembina group also spread out to a new location farther west, St. Joseph. This was just the beginning of what was to become a western migration following the buffalo as the herds receded farther and farther away from Red River.

For years the Sioux and the Métis had been sparring. Large Métis hunting parties now moved regularly into lands the Sioux regarded as its traditional territory. The Métis moved with caution, always ready for an encounter with the Sioux, but the large size of their hunting parties, their shooting skills and military discipline allowed them to penetrate farther and farther into Sioux territory. The Sioux hated the Métis coming into their territory, and they were further angered when Iron Alliance hunting groups included Ojibwa hunters.

The Ojibwa were the close relatives of the Métis but a bitter enemy of the Sioux. The animosity between the two traditional enemies was of long standing. The Sioux believed the Métis and the Ojibwa were trespassing, and they were prepared to kill both on sight. Peace broke out occasionally between the two tribes, and some Métis married Sioux and lived among them, including the influential Bottineau family. But these were small islands in the general animosity that characterized the relationship between the Sioux and the people who made up the Iron Alliance—the Assiniboine, the Ojibwa, the Cree and the Métis Nation.

Cuthbert Grant had a complicated relationship with the Sioux. He was the Warden of the Plains and it was part of his job to keep the peace in Red River. The Sioux were a constant source of worry for Red River and Pembina. In 1822 the Sioux killed twelve Métis. In 1834 the Sioux sent a delegation under one of their chiefs, La Terre Qui Brule, to the Forks. They wanted the Company to set up a post at Lake Traverse in Minnesota to provide competition to the American Fur Company. Hearing that the Sioux had appeared in the settlement, Cuthbert Grant, as he had in 1821, sprang into action. This time the encounter turned into an ugly standoff, which was defused with difficulty. All parties stood down, and fifty English Métis and settlers eventually escorted the Sioux out of the colony. It turned out the Sioux had been escorted into the settlement specifically in order to avoid an Ojibwa attack. If so, it was a poorly executed plan.

The Sioux were a large and magnificent group of warriors. They were well armed and mounted. The possibility that the Métis Nation and the Sioux would join forces was a constant worry for Governor Simpson, who was at Red River when another large Sioux delegation arrived in 1836. In 1839 the Métis travelled to Devil’s Lake in North Dakota to make peace with the Yankton and Sisseton Sioux of Lake Traverse. But the peace was fleeting. One of the problems was that although peace would be made with one group of Sioux, another group would not feel bound by the peace agreement, especially if family members had been killed. In that case deadly retribution was practically guaranteed, and this rough justice prevailed between the Sioux, the Ojibwa and the Métis. In 1844 there was a deadly confrontation between some Métis and the Sioux. Cuthbert Grant brokered the peace through an exchange of letters with Sioux chiefs.

This peace lasted for only a few years. In 1848 there was another large battle between the Red River Métis and the Sioux near present-day Oglala in South Dakota. The Métis captain of the hunt was Jean-Baptiste Wilkie, and the hunting camp was made up of eight hundred Métis men and two hundred Chippewa men. They all had their families, horses and over one thousand Red River carts. One final and decisive battle between the Métis and the Sioux, the Battle of the Grand Coteau, took place in 1851. It has remained an important story for the Métis Nation.

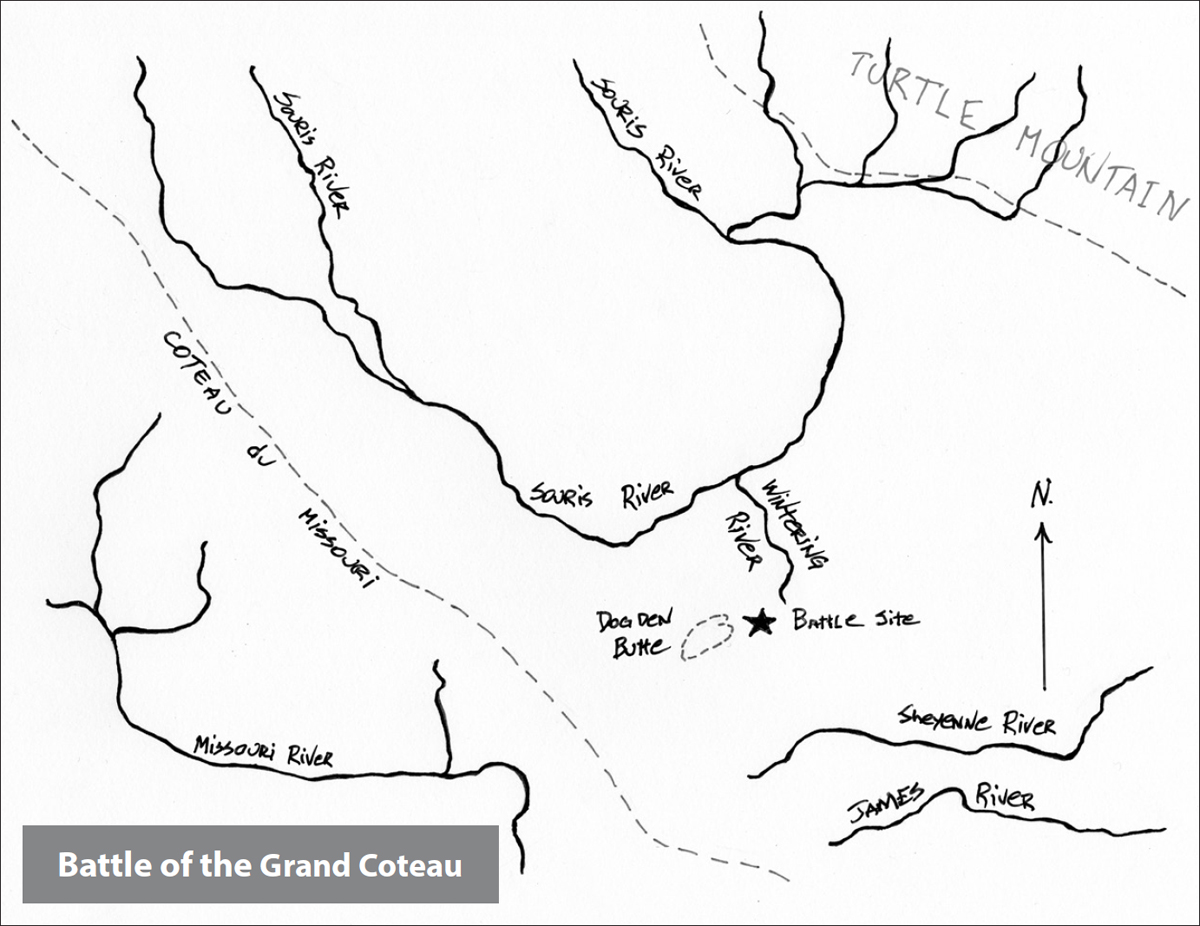

The Grand Coteau du Missouri is a stony plateau. At its foot flows one of the great bends of the Missouri River. The battle took place northeast of Maison du Chien, or Dog Den Butte, a very conspicuous butte that is visible for miles. It has a dark, sinister and dangerous air to it. At the time it was a well-known ambush location for the Sioux.

In 1851 the Métis hunters departed for the annual hunt as usual from the Forks, Pembina and the White Horse Plain. On June 15 the Pembina group and the Forks group merged at the rendezvous south and west of Pembina. Together they numbered about 318 hunters. With the women and children, the camp numbered thirteen hundred people in eleven hundred carts. The White Horse Plain group arrived with a smaller party.

When the White Horse Plain group arrived at the rendezvous, a general council was held and Jean-Baptiste Falcon, from the White Horse Plain group, was elected chief captain of the hunt.1 The groups decided to proceed in two columns. Separated by a few miles, the columns kept in contact and travelled in a generally parallel course. In fairly short order the White Horse Plain group encountered a Sioux camp, and not a small one. There were eight thousand Sioux against two hundred Métis carts with only sixty-seven men. Gabriel Dumont, who would become one of the great Métis hunters and their famous general, was in the Métis group. He was thirteen years old.

Scouts were immediately sent off to the larger Métis group, but the Sioux captured them before they could get very far. The Métis, with the precision of a veteran army, went into military defence mode, circling their carts, digging protective pits, readying their ammunition and guns, and settling in for a protracted siege.

The Sioux attacked. So sure were they of an easy victory and anticipating spoils, they brought women and children in tow. They brought the three hostage scouts closer to taunt the Métis. Two hostages took the opportunity to make a run for it. One made it to the Métis camp unscathed. One made it wounded. The third hostage was killed.

The Sioux thought the Métis would surrender when they saw the thousands of men attacking them. They were wrong. The Métis had no intention of surrendering. They vowed to fight to the death and fully expected that to be their fate. The Sioux were so surprised that the Métis didn’t scatter, they tried to scare them into flight. Their shots were not aimed at the Métis hunters, and they were more engaged in making noise and threats than in actually shooting to kill or disarm. The Métis had no such scruples. Their discipline and military prowess came to the fore, and they held up under six hours of sustained attack. Isabelle Falcon, sister of the captain of the hunt, was an impressive warrior.

[W]hen Jean Baptiste Falcon was going around acting as captain, his sister Isabelle was fighting in his place. She never left him alone during the three days battle, she would force him to rest and during that time she would shoot and she was a good shot too. Every time they would shoot, it was sure a Sioux would fall. And they would shoot from sunrise to sunset everyday.2

The Sioux withdrew to their own camp for the night, and under cover of darkness, the Métis sent two men to the other Métis caravan for help. The next dawn brought a renewal of the battle. The Sioux pressed harder but after five hours made no dent in the Métis defence. Then, to the surprise and relief of the Métis camp, the Sioux quit. They gave honour to the Métis as victors, gathered their dead and withdrew. It is estimated that by the end of the battle, the Sioux had lost between eighty and ninety warriors. The Métis lost one man.

That was the last such battle. Thereafter the Sioux acknowledged the Métis as “Masters of the Plains” and would fight them no more. The Métis Nation had fully come of age. No longer was this the gang of 1816 who claimed to be a nation. Generations had grown up in the belief that the Métis were a nation. Their organizational and military skills garnered them a victory that no one expected. The Sioux, the terror of the Plains for decades, had been defeated. The Métis had acted as a disciplined army, protected their interests as a collective and were victorious as one.

The Métis Nation had now carved out a place for itself. By marriage they were kin with the Assiniboine, Ojibwa and Cree. They travelled and hunted together and in mixed parties, and they were part of the Iron Alliance. According to the Assiniboine, the Métis were born on the same soil and had the same blood in their veins. “These we cannot and will not harm, they have the same right on these prairies as ourselves.”3

Now the Métis were a nation in fact, not just in aspiration or name. In 1816 they had proclaimed the Métis Nation and now they had made it so. They celebrated their victory over the Sioux with songs and dances that carried on for days.