LII CANADAS

The Métis Nation settled into a pattern after the Sayer trial. They had successfully asserted their rights as a nation, as a collective force to be reckoned with in Red River. They continued to assert their existence as a “Native” nation, distinguishing themselves from First Nations and Euro-Canadians.

But there was a sense that change was coming. The leading minds of the Métis Nation could see that Britain’s interest in the North-West was waning. And men of a different ilk were beginning to arrive in Red River. Before 1850 the Métis Nation had known mostly fur traders and Selkirk Settlers. But the population of Red River was growing, and by 1856 there were 6,523 people.

The newcomers were different. They were aligned with the Canada First movement in Ontario. They had two goals: ensuring that Canada became British and Protestant, and annexing the North-West to Canada.1 The Canada First movement campaigned for exclusively British immigration and championed the idea of an Anglo-Saxon, Protestant northern race with superior values and institutions. Ontario premier Edward Blake and the Conservative minister of public works William McDougall were both members of the Canada First movement. Their point man in Red River was John Christian Schultz, the founder of the Canada First branch in the North-West, which he named the Canadian Party. Schultz was a shady manipulator and fraud artist.2 Many years later when he died, it was said, “Pity we knew him.”3 Unfortunately, we will get to know him quite well. The Métis called these men lii Canadas, the Canadas. It wasn’t a compliment.

The Canadian Party established a newspaper in Red River, called The Nor’-Wester. Although the term “yellow journalism” would not be coined for another thirty years, The Nor’-Wester was an early practitioner of this sensationalist style of reporting. Facts and integrity were not entirely absent in The Nor’-Wester, but the slant of the message was more important than inconvenient facts. The Canadian Party was in the newspaper business so they could control messaging to their target audience, Ontario. But their main interest was land. They wanted Canada to annex the North-West so the land could be opened up to the market. As the earliest opportunists on site, they dreamed of fortunes—a dream that required a significant investment in time and effort.

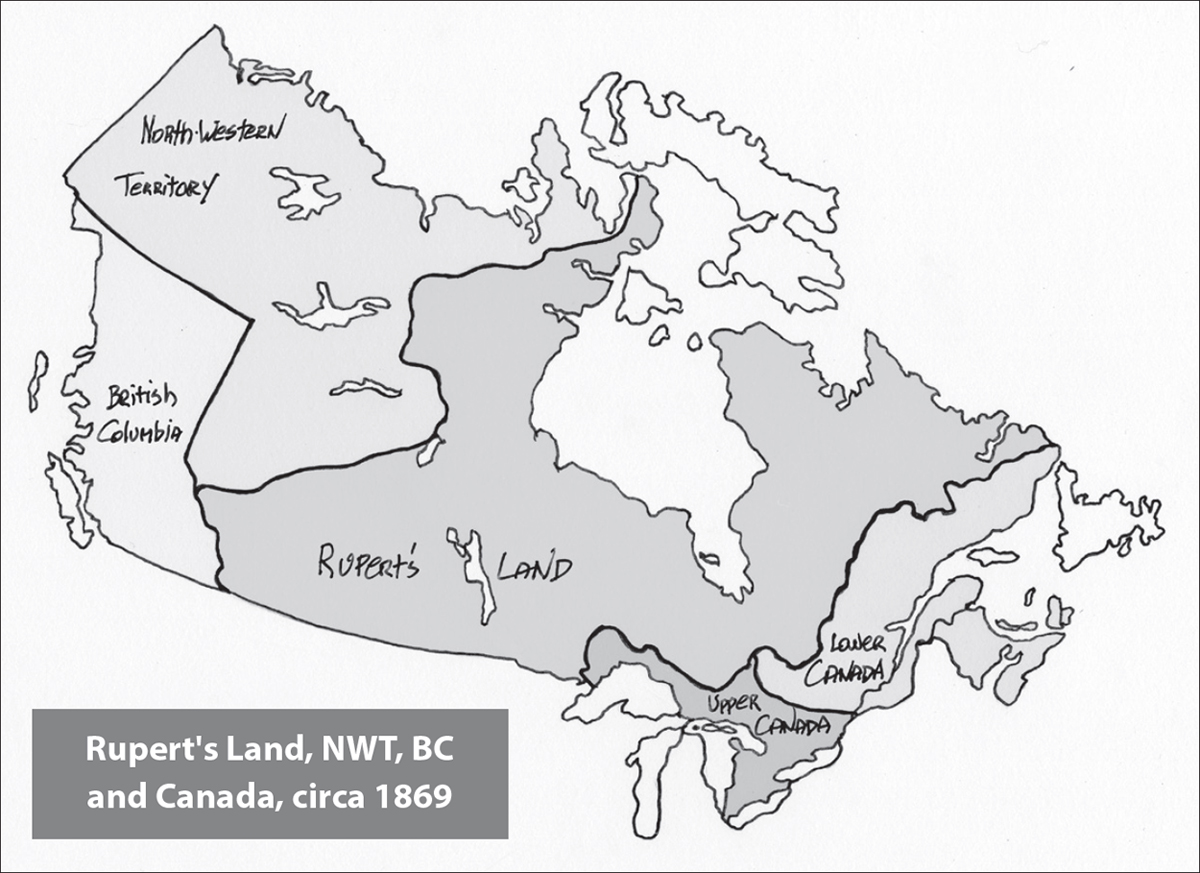

Converting the lands of the North-West into a market was a multi-step process. The North-West would have to change hands four times before the Canadian Party men could turn a profit. First the Hudson’s Bay Company would have to transfer Rupert’s Land back to Britain. Then Britain would have to transfer Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory to Canada. Once the entire North-West (Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory) was annexed to Canada, the Canadian Party speculators could buy plots of land. Then they needed people. Hence the message of the Canadian Party newspaper to Ontario, praising the glories of the North-West. They wanted mass immigration of a very specific kind—farmers, preferably white, Protestant, English-speaking people from Ontario. When the proper kind of Ontario immigrants arrived, the speculators could sell them land and only then realize a profit.

Step one was to eliminate the Hudson’s Bay Company, the owners of Rupert’s Land. Using their newspaper, The Nor’-Wester, Schultz and his party mounted an assault on the Company. They had great supporters in Ontario and in the Canadian government, but they also needed to convince the residents of Red River of their plan. In particular they wanted to convince the Métis Nation leaders, men like Pascal Breland and Jean-Louis Riel, that annexation to Canada was good for Red River. Jean-Louis Riel seemed like a natural ally because he had been one of those who led the charge against the Company in the 1840s. So, Schultz and his party set up an annexation meeting and asked Riel to chair it. The Canadian Party came out in full force and the meeting quickly descended into a bash-the-Company session. Seeking to provide some balance, Riel invited Father Bermond to speak in support of the Company. But the Canadian Party men were not subtle practitioners of the art of persuasion. They heckled Bermond and shouted him down. The meeting ended in disarray. If the Canadian Party called the meeting to persuade the Métis of the benefits of annexation, it cannot be considered a success.

The meeting sparked the Métis Nation to respond. Jean-Louis Riel took to contradicting the Canadian Party claims that dissatisfaction with the Company was universal, stating flatly that among his people there was no such dissatisfaction. It was an interesting change of position for the Métis Nation. A decade before they were the ones haranguing the Company. But since the Sayer trial, they were less inclined to fight the Company.

Things had changed. The Métis were included in the governance of Red River through their representatives on the Council of Assiniboia. They were trading freely and they were co-operating with the company court when it suited them. Perhaps more to the point, the Métis were less dependent on the Company. Many Métis were spending more time away from Red River as their buffalo hunts took them farther west for longer periods of time. They were fostering a trading relationship with the Americans and building their own wintering settlements on the Plains. Because the Company no longer ruled every aspect of Métis lives, their attitude toward the Company had mellowed.

It was the Canadian Party, trying to set up at Red River, that felt the bite of the Company’s monopoly over governance (from which they were excluded) and its court (which more than once found against Schultz). And it was these newcomers who created the insecurity everyone in Red River now began to feel about their land title. In taking the first steps to create a market for land, they drew attention to the fact that most land in Red River was held under Métis customary law. Very few Métis had paper title from the Company proving their ownership. It drove the Métis Nation to hold a large meeting in 1862 to assert their native claim to the land.

WEATHER, DISEASE AND INSECTS

Floods, fires, drought, disease and insects all took a toll on the Métis Nation during the 1860s. There was famine in 1862 and 1864, and scarlet fever, typhus and dysentery in 1864 and 1865. In 1865 the French Métis parishes in Red River buried three people a day. Floods in 1865 and 1866 brought clouds of mosquitoes in 1867. And then the grasshoppers appeared. In the course of destroying the crops, the insects laid their eggs, and in the spring of 1868 a new generation appeared. The grasshoppers stripped the woods and fields bare and devoured every last leaf and head of grain. The entire country looked and was destitute. The loss of all vegetation meant the buffalo kept a wide berth. The hunters arrived back in the settlement starving, their hunt having failed. The fisheries failed and even the rabbits and pheasants disappeared. Many people died from the collective toll taken by the floods, fires, drought, disease and grasshoppers. Famine stalked the North-West.

There were celebrations in eastern Canada for the first birthday of the country on July 1, 1867, but few celebrated in Red River. Canada’s reputation in Red River was, to say the least, not good. As Louis Goulet said, “These émigrés from Ontario, all of them Orangemen, looked as if their one dream in life was to make war on the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Catholic Church and anyone who spoke French. In a word, as my father put it, the devil was in the woodpile. The latest arrivals were looking to be masters of everything, everywhere.”4

The Canadian Party was sowing seeds of racism, bigotry and religious conflict. The Canadian Party and the insects were both wreaking havoc. At least the grasshoppers ate and left. The Canadian Party stayed, thrived on the conflict it sowed, and gave the Métis Nation its first indication that it had something to fear and a lot to lose by joining Canada. The conflict began with a road.

THE ROAD RELIEF SCAM

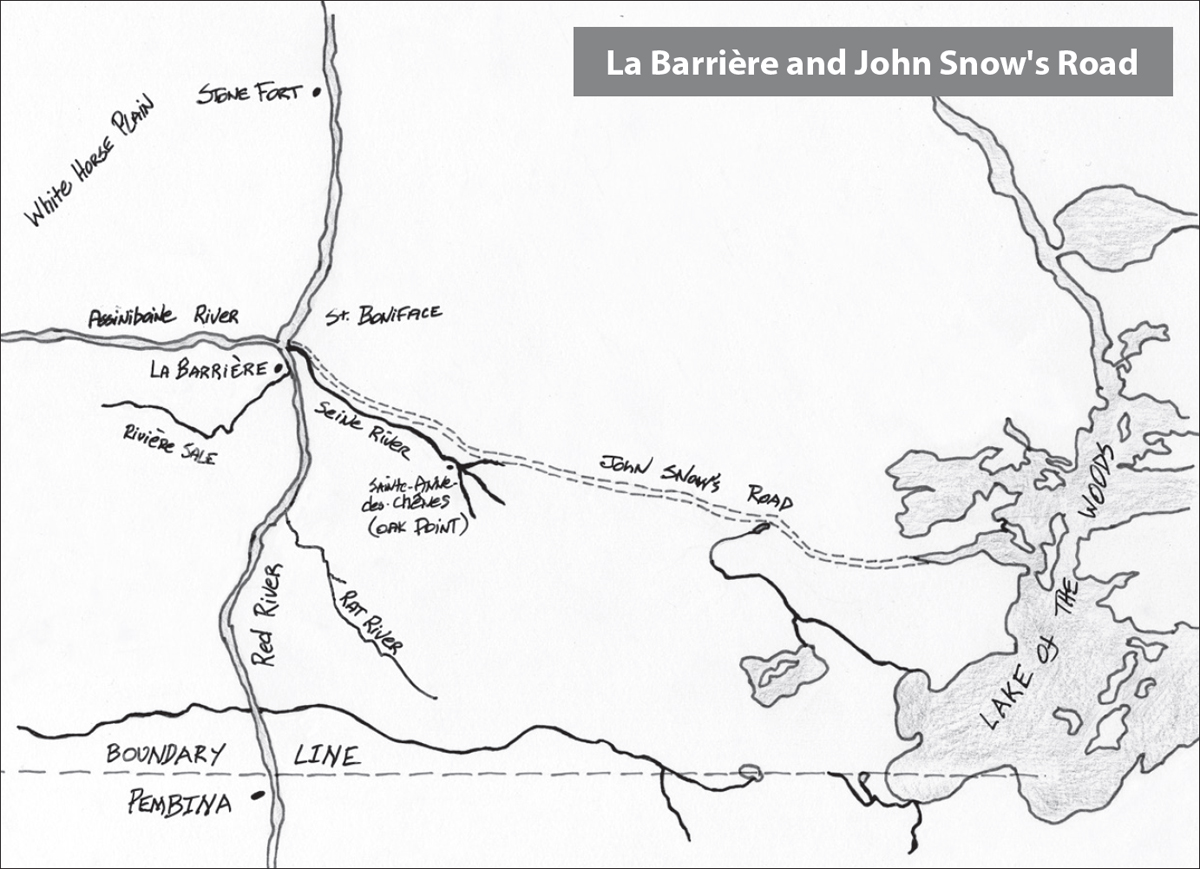

Since Confederation in 1867 Canada had been preparing to accept the North-West from Great Britain. In 1868 the complicated negotiations began. Until the North-West was officially transferred, Canada was a foreign country with no rights or claims west of Ontario. But Canada was lusting after the North-West, and the famine in Red River provided an opportunity for Canada to send men to the North-West. Under the guise of a work relief project and with no prior permission from the Company, Canada authorized the construction of a road between Lake of the Woods in Ontario and Red River.

The project was a Conservative Party boondoggle. John Snow, the lead surveyor, arrived in Red River in September 1868 with his paymaster, Charles Mair. Mair was one of the founding members of the Canada First movement. Both men fell into a natural alliance with Schultz and the Canadian Party. Their Canada First brother, who was the Canadian minister of public works, McDougall, provided $30,000 for the road relief project, money that was supposed to benefit the people of Red River who were suffering from the famine. Most of that money stayed in the hands of the Canadian Party.

Schultz opened up a store in the Métis community of Oak Point (Sainte-Anne-des-Chênes).5 Road workers were paid in goods from Schultz’s store, where provisions cost more than the men earned. Shopping at Schultz’s store was particularly galling to the Métis workers on the road project because Schultz made no secret of his utter contempt for the Métis.

Snow and the Canadian Party then developed a scheme to buy land nearby. Snow sold liquor to the Ojibwa and then held a meeting at which they, under the influence, “agreed” to sell their Aboriginal title. Snow’s men plowed out claims for large tracts of land. They boasted that as soon as Canada took possession, their claims would be secured. The road workers broke into Métis houses and took them over for long dancing and drinking parties. The terrified women and children were held prisoner and prevented from escaping for help. The Métis leader in Sainte-Anne-des-Chênes was Augustin Nolin, and he was not a man who would complacently accept any interference with his family, his land or his relatives, the Ojibwa. Nolin seized Snow and brought him to Fort Garry to be dealt with by the Court of Assiniboia.

From these events we can learn two things: First, Métis leaders were prepared, as always, to take action to protect their family and their rights. Second, this was the kind of case they were confident could be dealt with by the Court of Assiniboia. If Nolin threw Snow to the Court of Assiniboia for justice, it was because in this situation, at this time, he believed justice could be found there.

After this episode Snow made peace with Nolin, which turned out to be a smart move. The road project never ran smoothly and experienced labour unrest all through its construction. It is here, on the relief project, that we first catch sight of Thomas Scott, the man who would cause so much trouble over the next three years. Scott was one of the road workers on the relief project. After a wage dispute, Scott and his road worker buddies tried to drown Snow, and it was Nolin who came to Snow’s rescue.

Hudson’s Bay Company governor William McTavish eventually registered a mild complaint about Canada’s trespass in building the road on Company land. McDougall justified the trespass by claiming that Canada felt obligated to provide assistance because the Company had done nothing for the starving people of Red River. This was blatantly false, but McDougall saw the road as an opportunity to get into the North-West. He wanted to see just what future opportunity and fortune Canada was about to purchase.

The road became a symbol for the Métis of what could be expected from Canada: corruption, violence and land swindles, all accompanied by a racist, anti-French, anti-Catholic, anti-Métis agenda. The first view of what it would mean to become Canadian was bleak. It was slightly less offensive for the English Métis. Though they were held to be inferior because of their Indigenous blood, they were more acceptable because they were Protestant, more invested in agriculture and spoke English. The French Métis had three strikes against them. They were “too Indian, too Catholic and too French.”6

ANNIE MCDERMOT BANNATYNE AND LOUIS RIEL

In addition to his Canada First activities, the paymaster of the road relief project, Charlie Mair, was something of a literary man. His letters, published in the Toronto Globe, claimed the Métis were making undeserved claims on the Red River Famine Relief Fund. They were, he claimed, “the only people here who are starving. Five thousand of them have to be fed this winter, and it is their own fault—they won’t farm.”7 Mair was living off the proceeds of the so-called famine relief project, so his comment about the Métis irritated everyone in Red River.

Many Métis did farm, but farming saved no one from the grasshoppers, which were equal opportunity pests, affecting the entire community. Most people needed help. In fact the starvation faced by the Métis hunters in the settlement was unusual. The hunt seldom failed; the crops failed regularly. Generally, it was the hunters who came to the rescue of the farmers. The Canadian Party may have appreciated Mair’s wit, but his letters wouldn’t make him friends in a community where the Métis formed over three-quarters of the population.

Mair’s published literary efforts also included a gossipy snarl aimed at the Métis women. “Many wealthy people are married to half-breed women, who, having no coat of arms but a ‘totem’ to look back to, make up for the deficiency by biting at the backs of their ‘white’ sisters.”8 Given that almost no Canadians looked back to a coat of arms, Mair’s comments were snobbish in the extreme. His British Protestant superiority influenced him to commend the hospitality he had received from Governor McTavish and his brother-in-law Andrew Bannatyne, but in the next breath he commented on the “deficiency” in their wives, the Métis sisters Annie and Mary Sarah McDermot.9

Annie McDermot Bannatyne is remembered rather fondly in Métis lore because she took on Charlie Mair. When by chance Annie met Mair at the local store, she took her horsewhip to him. Everyone in the settlement was delighted with Annie. They appreciated her method of administering what they saw as a well-deserved public humiliation of a man who had abused their women. Mair kept his opinions on Métis women to himself after this public chastising. But of course the whipping didn’t change his contempt for the Métis.

Jean-Louis Riel’s son Louis raised his voice in public for the first time and challenged Mair in the press. In a letter to the editor of Le Nouveau Monde, Riel pointed out that the famine struck members of all segments of Red River society and that Mair had his facts wrong. Riel gave voice to the Métis’ low opinion of Mair: “[I]f we had only you as a specimen of civilized men, we should not have a very high idea of them.”10

Riel had been away in Quebec and in the United States. He arrived back in Red River on July 26, 1868. He was twenty-four years old and came home to find his people obsessed with the coming transfer. They were all talking politics. The Métis Nation’s political force, always simmering, was starting to boil up again. In the past the Nation had faced off against the Selkirk Settlers and the Hudson’s Bay Company. Now it was facing a new threat: Canada as represented by the Canadian Party. Riel’s letter marked his first foray as the voice of the Métis Nation, and with it he burst onto the Canadian consciousness. The comet had appeared in the sky.

Louis Riel (Glenbow Archives NA-47-28)

SOLD

It occurred to no one in the government of Great Britain or of Canada to inform the Métis or anyone in the North-West about their plans. To the extent that the Canadian government gave it any thought at all—and it really didn’t—the scattered nomadic First Nations and the Métis were not considered worth the effort. Canada gave no legal credit to the Hudson’s Bay Company charter and dismissed its government, the Council of Assiniboia, as a nonentity. As far as Canada was concerned, the North-West was a vast and empty land, theirs for the taking.

Canada knew there were Indigenous people in the North-West, although they didn’t know who, where or how many they were. To Canada’s way of thinking, the only issue was the extinguishment of Indian title, a matter they considered a mere administrative detail that could be dealt with later by treaties. The idea that there was such a thing as a collective Métis people, the Métis Nation, never entered their minds. The poet e. e. cummings’s line “down they forgot as up they grew” captures Canada’s convenient memory lapse perfectly.11 Canada had forgotten the 1816 battle at the Frog Plain and succumbed to the propaganda published by the Canadian Party.

Both Britain and Canada proceeded as if only land were being transferred. Britain hoped it could transfer the land without Canada looking too deeply into the fact that the natives in the North-West had proven themselves restive in the past and could likely be counted on to behave so again. Britain also wanted to avoid any legal battle over the legitimacy of the three-hundred-year-old Hudson’s Bay Company charter. Canada was urged to keep its eye on the main issue, the land, and just cut a deal. In the end Canada decided it could overlook the legitimacy of the charter. A bargain was made—and a bargain it was: 1.5 million square miles for £300,000 ($1.5 million). To put it in perspective, the United States had recently paid Russia $7.2 million for nearly 600,000 square miles when it purchased Alaska.

Both Britain and Canada were warned about the rising discontent in the North-West. All warnings were dismissed. Canada purported to be fully aware of everything it needed to know about the people and issues in the North-West and had everything entirely under control.

THE MÉTIS NATION FORCE BEGINS TO STIR

The Métis Nation was worried about the security of their motherland, and they suspected, correctly, that they would be excluded in the new government. Their objections were published in the The New Nation, a newspaper printed in Red River between January and September of 1870 that generally supported the Métis:

They aver that they do not belong to Canada, and have never been made over to that Dominion. That although the Canadian Government has given £300,000 to the Hudson Bay Company for certain territories which belonged to the latter, they are not included in this bargain, seeing that they never were an appendage to the Hudson Bay Company; that Canada could not buy what it was not the company’s to sell; that, in any case, they ought not to be transferred to a third power without their leave and consent; that, if they have been a British settlement hitherto, they have as much right to be consulted as to their disposition as were the people of Prince Edward’s Island, Newfoundland, and British Columbia, all of whom have been invited, but have declined, to enter the Confederation, and yet whom the Canadian Government has never pretended to have the right to coerce, or to bring within the Union, whether they would or not. The people of the Red River territory, in fact, decline to be sold as a chattel of the Hudson Bay territory . . . and they protest that, if they are British subjects at all, they are the subjects not of Canada but of England; that they are a colony of England, and not “a colony of a colony.”12

Their worst fears were confirmed in June 1869 when Canada revealed its plans for governance of the North-West. Canada would henceforth have its own Crown colony in the North-West with a lieutenant-governor and a council appointed from Ottawa. The lieutenant-governor was to be the “Paternal despot, as in other small Crown Colonies, his Council being one of advice, he and they, however, being governed by instructions from HeadQuarters.”13

The proposal was a great step backwards for the people of the North-West. While the Council of Assiniboia was not an elected government, it did contain appointed members recommended by the residents, and it had learned to ensure that the various sectors of the colony were given voice in the council. This is why Jean-Louis Riel had confidently stated that the Métis had no complaints about the Company. Canada’s proposal of a government composed only of easterners accountable to, appointed by and directed from far away was unacceptable to the Métis Nation.

The English-speaking population of Red River, largely made up of English Métis, was concerned about its future but inclined to believe that everything would be fine and there was no need to get involved. The French Métis were not so complacent. Everyone had heard the Canadian Party boast that they “would take up arms and drive out the half-breeds.”14 They “would all be driven back from the river & their land given to others.”15 There was no way the French Métis were going to sit quietly and let this happen.