THE FRENCH MÉTIS TAKE ACTION

The Red River Resistance began on July 5, 1869. Prior to this the Métis Nation had been passionately debating how to protect its rights and existence as a nation. Now they began to take action. It began when the French Métis in St. Vital and St. Norbert found men from Canada’s road project, including Charlie Mair, staking claims on their lands. The Métis ordered them off and began to send out regular mounted patrols with orders to protect Métis lands from the speculators. The Métis patrols evicted squatters, chased away claim-stakers, removed stakes and signs of occupation, and filled in any wells they found. They chased lii Canadas to lands near Portage la Prairie.

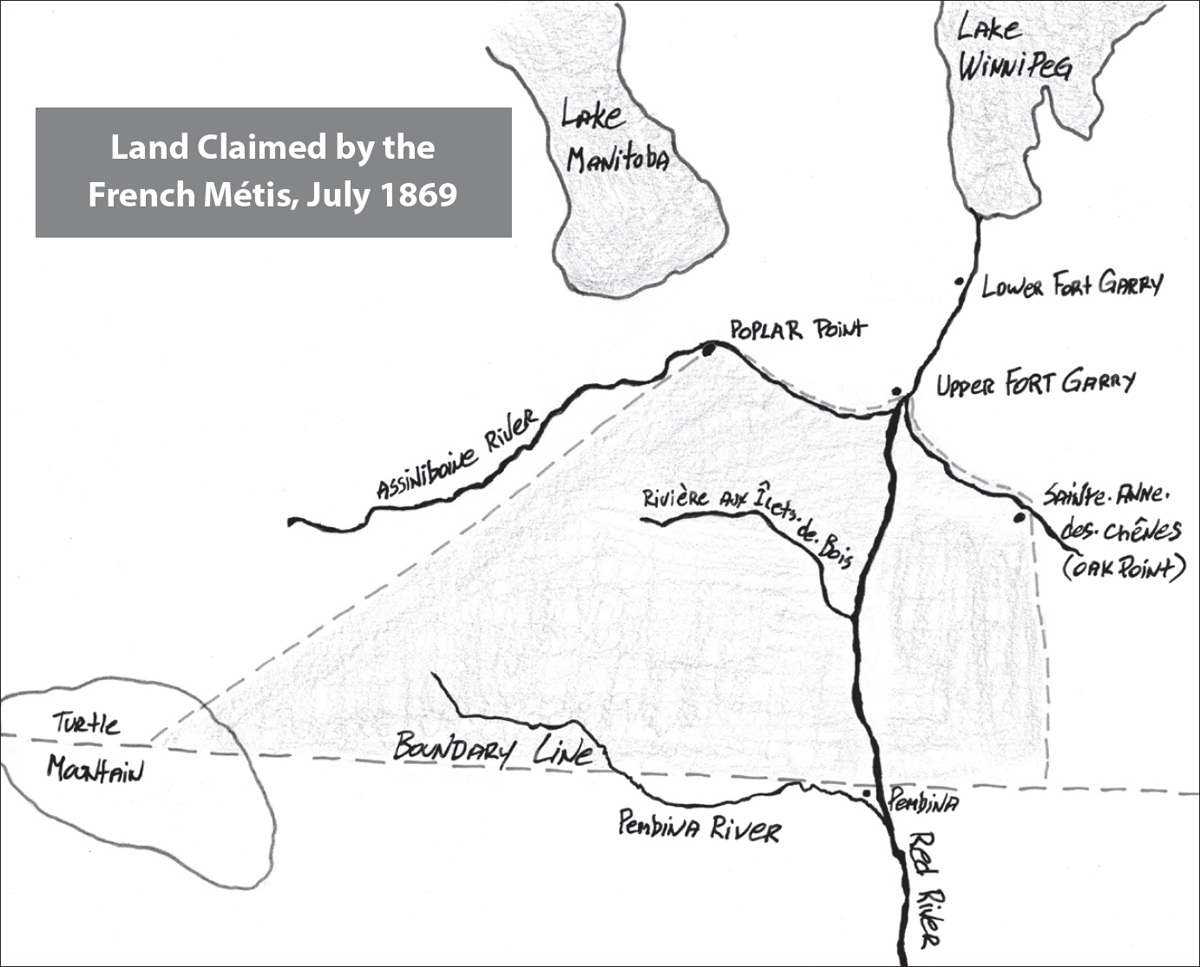

They also claimed a specific territory, which they described as their collective lands, recognized by the custom of the people or by agreement of their nation.1 They expressly excluded strangers. At this point, July 1869, the French Métis marked out only their own territory. They did not include the English Métis parishes.

While the French Métis were taking action to identify and protect their territory, the Canadian Party was trying to drum up support for annexation to Canada. Some prominent Métis traders such as William Dease, Georges Racette and Pascal Breland stood to gain a great deal from more customers and new markets for their goods. Dease had particularly ambitious plans. In addition to annexation he wanted to overthrow the Council of Assiniboia, be named governor and appropriate the £300,000 Canada was paying Great Britain for the North-West. He announced his grand plan at a public meeting on July 29, 1869. It didn’t go well.

The Métis were ready to listen to someone with a plan. But they didn’t like his. They were suspicious of Dease’s connections to the Canadian Party, and they knew that overthrowing the Council of Assiniboia could not be done without them. If the Canadian Party, via Dease, could get the Métis to overthrow the council, Company rule would collapse like a house of cards. The resulting chaos would open the way for ambitious men to claim land and make fortunes. It was a classic example of what Naomi Klein calls “the shock doctrine,” where planned chaos provides opportunities for speculators. Overthrowing the Company government would have benefited the men of the Canadian Party and perhaps a few traders like Dease. It would be of no benefit to the Métis. Schultz and his ilk didn’t believe the Métis had rights, but they knew the Métis claimed them. This would be a cheap and easy way to overthrow the Company and use its money to buy off the Métis.

Dease’s proposal was particularly shocking because he was a Métis representative on the Council of Assiniboia, an appointed member of the very government he was now proposing to overthrow. Those in attendance had no objection to demanding the money from Canada. There was nothing to be lost by such a demand, and who knew, maybe they would get something. But they objected to everything else Dease proposed. John Bruce, an English Métis, rose to object. Bruce was a man of some stature in the Métis community. So when he expressed his disapproval, the people listened and most agreed.

The Métis Nation has never made its decisions by consensus. They are prepared to argue passionately for a long time in the decision-making process, but in the end, they always vote and the majority rules. They vote often and on even the smallest decision. So Dease’s proposal went to a vote. A few supported Dease, but the majority, by a long shot, were opposed and left the meeting considering a petition to publicly condemn Dease. Dease’s attempt to become the governor of Red River and the leader of the Métis Nation failed.

The Métis would not go down the route Dease had mapped out, and for good reason. The problem didn’t lie with the Company, which the Métis saw as a spent force. The problem was Canada. Overthrowing the wrong target would be foolish. And the Métis were not prepared to follow a leader who urged them to act in what was so obviously his own self-interest. Dease left the meeting ashamed, “like a fox caught by a hen.”2 The French Métis in St. Norbert and St. Vital continued protecting their territory with their mounted patrols, and they continued meeting to make their own plans.

THE SURVEYORS ARRIVE

The next step toward colonization of the North-West began in July 1869. Canada still had no legal right to do anything in the North-West until after the land was transferred from Great Britain to Canada on December 1, 1869. But the legalities didn’t trouble William McDougall. After all, he had sent in the road crew with only a mild protest from the Company. Anticipating no resistance from it, McDougall sent in surveyors.

The surveyors, led by Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, arrived in Red River in August 1869 and, like the road relief crew before them, immediately took up with the Canadian Party. This made the Métis suspicious of their survey objectives. Augustin Nolin sent Dennis a letter telling him not to come out to Sainte-Anne-des-Chênes if he wanted to keep his head on his shoulders. Despite the warning several surveyors began staking out claims at Sainte-Anne-des-Chênes, again boasting that such claims would be recognized by Canada. Nolin and his men forcibly removed them and obliterated any signs of their claims.

The French Métis saw the survey as a move by Protestant Ontarians to take their lands and to interfere with their rights. Their worry about the vulnerability of their lands was not misplaced. The draft plan for bringing the North-West into Canada provided no protection for the Métis Nation or its lands. Canada’s plan proposed to recognize and confirm only the titles conferred by the Company before March 8, 1869. But most Métis lands had not been conferred by the Company. Their lands were held according to their customary laws. Canada’s proposed law left the Métis Nation in Red River feeling very vulnerable.

It is not an exaggeration to say the survey project set the North-West on fire.

CANADA BLUNDERS ALONG

On September 28, 1869, William McDougall was appointed lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territories, an appointment that was to take effect after the transfer on December 1, 1869. The appointment of McDougall was a blunder, much like so many of the previous appointees to Red River. McDougall was known, not affectionately, as Wandering Willie—a moniker earned as a result of his constant and blatant search for political opportunity. In Red River he already had a bad reputation. It was McDougall who had sent in the road relief project and the hated surveyors. Both groups had tried to claim Métis land. These were facts.

Rumours painted McDougall as a priest killer. He had had a run-in with Jesuits and Ojibwa at Manitoulin Island a few years before, but the rumours were exaggerations with respect to the priests. He hadn’t killed them. Still, the Manitoulin incident provided insight into the kind of ruler he would be. At Manitoulin McDougall had imposed a law to remove Ojibwa access to an important fishery. Under the new law only those licensed could fish. The Ojibwa were not granted licences and suddenly had no right to use their traditional fishery. According to McDougall this was “the majesty of the law.”3

The Métis Nation feared the same legal sleight of hand would obliterate their lands and resources. McDougall, a prominent member of the Canada First movement, was anti-Catholic, anti-French and anti-Métis—everything the French Métis feared from Canada. He would be in a powerful position to favour everyone in the settlement but them. He would have the power to grant their lands and resources to newcomers and then claim the majesty of the law, as he had done in Manitoulin, thus making the Métis criminals for trespassing on their own lands, and thieves for accessing their own resources. They warned McDougall that if he showed himself in the country, he would be told to go back to Toronto.

At the time, the Métis may not have known the prime minister’s exact plan for Red River, but they were beginning to get the drift. They were expendable in the coming scheme. Indeed John A. Macdonald did have a plan for them. He was going to “keep those wild people quiet. In another year the present residents will be altogether swamped by the influx of strangers who will go in with the idea of becoming industrious and peaceable settlers.”4

The appointment of McDougall provoked the French Métis leaders to increase their meetings, and they began to discuss asserting their collective identity as the Métis Nation as the means of resistance to the coming invasion from Ontario. They were already taking action against the Canadian Party attempts to claim their lands. Unfortunately, their leaders were unable to harness the discontent and gather a consensus about what to do about the coming annexation.

The younger generation of Métis were not content to sit and wait for Canada to come in on its own terms, and they were not going to follow the lead of men like Dease. Perhaps these men were seen as too connected to the Canadian Party. Perhaps they were seen to be acting in their own personal interests. Perhaps they were seen as old codgers unable to connect with the younger generation. Likely it was a combination of all of these factors.

It was in this milieu that Louis Riel—a young, articulate, well-educated Métis, with no connections to the Canadian Party, who was not seen to be acting in his own interest, and the son of a deceased but well-respected Métis leader—emerged as the one man who could organize and lead the resistance of the Métis Nation.

STOPPING THE SURVEYORS

The French Métis, especially the young men, began to listen to Riel and to ask his advice. He was educated and he spoke English, so they asked him to find out what the surveyors were doing. Riel met with Colonel Dennis, who assured him that the intention was to survey “all the lands occupied and to give the parties in possession of lands Crown deeds free.”5 Riel listened politely, but what he heard was not reassuring.

It was the “parties in possession” part that was worrisome. When the Métis spoke of the lands they possessed, they meant their lands held under paper title or pursuant to Métis custom. They also considered the lands they possessed to include their access to common lands. The commons was part of their traditional land-use system, and it worked perfectly for their small farms, which required access to the riverfront, land for a house and garden, plus access to commonly held lands for hay and wood. The surveyors were treating the common hay lands and woodlots as vacant.

Once the survey was completed, the land use in Red River would change forever. The new system would ignore Métis land knowledge and their systems of common land use. The surveyors, newly arrived, certainly saw the existing system, but they made no attempt to protect it. There was no room in their survey system for commonly held land.

Since July Métis patrols had been stopping any attempts to stake, build or dig wells in their claimed territory. On October 11, 1869, Major Adam Clark Webb was running survey lines on Edouard Marion’s hay privilege in St. Vital. A Métis patrol encountered Webb’s party and attempted to stop the survey. But the patrol was made up of French-speaking Métis, and Webb and his men spoke only English. The patrol sent for Louis Riel, and on his arrival eighteen unarmed Métis confronted the survey party.6 There was no violence. Riel simply ordered the surveyors to stop running the lines and “to leave the country on the south side of the Assiniboine, which country the party claimed as the property of the French Half-breeds, and which they would not allow to be surveyed by the Canadian Government.”7 Janvier Ritchot stood on the survey chain first and then the rest of the Métis party did the same. There would be no more surveying on Métis lands.

THE RIFLES

Riel and the Métis went unarmed to challenge the surveyors. That was before they found out about the rifles—a Canadian government shipment of one hundred Spencer carbines and two hundred and fifty Peabody rifles all equipped with bayonets and accompanied by eight to ten thousand rounds of ammunition.8 Word of the rifles spread through Red River before they even arrived. No goods or people arrived in the North-West without the knowledge of the Métis. The new governor was coming with rifles—lots of rifles. Why would a new governor come with any arms at all, let alone so many? Who was going to be armed?

This then was what the Métis understood in October 1869. Canada was sending a well-armed governor. The surveyors were military men, with military titles such as major and colonel, and packed uniforms in their luggage. There were more ex-soldiers in the road relief crew. All these men had been sent into Red River by Canada. Canada was no longer just a political threat, something that could be talked out. It was now a military threat. Canada was taking over and it gave every indication that it was going to use force.

For the Métis Nation, knowledge of the rifles changed everything. The idea of joining Canada was not the problem. But the terms of the new relationship needed negotiation so that unity would be achieved for the right reasons—voluntary inclusion, equal participation and mutual compromise—thereby achieving a collective endorsement of what would become new and inclusive principles and institutions of Canada. That’s what everyone in Red River wanted.

What Canada thought it was doing is difficult to fathom. Canada made no attempt to understand or to encompass the vastly different principles that guided the people of the North-West. Herein lies the root of all the discord between the Métis Nation and Canada that was to follow in the North-West. Even on the most basic political level, it would have made sense for Macdonald to make new friends and not alienate future voters. He had just negotiated Confederation. He knew that even small provinces have demands, one of which is respect for their jurisdiction and power. Nova Scotia in particular had resisted Confederation, at least in part, because of the lack of consultation.

Why would Macdonald think the North-West was different? In 1870 the population of Red River was approximately twelve thousand. Eighty-five per cent were what we now call Métis. Almost eight thousand were under the age of twenty-one. The four thousand adults were almost equally divided between French and English. It is difficult to avoid concluding that it was because Macdonald didn’t consider the adult inhabitants of Red River, overwhelmingly Métis, capable or worthy of consultation or negotiation.

The Métis stepped on the survey chain on October 11, 1869. No Métis went to that confrontation armed. But when they learned about the stash of rifles and ammunition and put that together with the Canadian military men already in Red River, the French Métis reached for their arms and started to organize more seriously. They created the National Committee of the Red River Métis with John Bruce as president and Louis Riel as secretary.

The National Committee was charged with instituting not British law but their own Métis Nation laws—the laws they had developed since 1816, the Laws of the Prairie. They began with their usual organization, the same one they had finely honed during many years of buffalo hunts. It would be a stretch to call the Métis organizing efforts at that stage a government, but they were well organized, they were reinforced by men with quasi-military skills, and they had specific goals.

The Métis in the English parishes were not far behind. They met a few days later in St. Andrews. They agreed that Red River should enter Confederation on equal terms with the other provinces and that they were fully competent to manage their own affairs. They also thought they should have their land title and access to resources protected. They too were angry about not being consulted and were concerned about the military nature of the incoming envoy from Canada.

At this point the English Métis differed from the French Métis only in tactics. The French Métis believed that immediate direct action was required before Canada could be allowed to come into the territory. The English Métis were prepared to let Canada in first and hope it would all work out. Despite the fear that Canada was about to use force, everyone in Red River held meeting after meeting to peacefully debate the future. They demonstrated an astonishing faith in democracy in the face of Canada’s obvious lack of the same.

LA BARRIÈRE

The French Métis didn’t wait for the English Métis to come around to their way of thinking. They didn’t want to lose the initiative. On October 17 they made their third move. André Nault took forty men to construct what would soon come to be known as “La Barrière” across the road at Rivière Sale.9 The barrier was constructed to prevent McDougall and “other suspicious persons, entering the Red River Colony . . . who might be carrying weapons or other objects considered to be dangerous to the peace.”10 By this time there were almost three hundred armed French Métis gathered at St. Norbert.

The rifles suggested that McDougall was arriving with an army. So the National Committee mounted a military expedition to stop him. When they learned that McDougall’s party was an unarmed entourage that included women, they set aside their military expedition. Instead they sent a letter to McDougall warning him not to enter the colony without the express permission of the National Committee of the Red River Métis.11

On October 24 the Canadian Party sent Dease and Georges Racette to St. Norbert, hoping to persuade the French Métis to dismantle La Barrière and clear the way for McDougall to enter. Dease squared off against Riel. After a long argument they did what the Métis always do; they voted. The question put to the vote was whether it was necessary to protest against the way Canada was going to impose its governance on the country. The vote carried unanimously. Even Dease and his followers agreed on the necessity of protesting. They also agreed to step aside and not hinder the efforts of the activists.

RESISTANCE NOT REBELLION

The Council of Assiniboia sent for Bruce and Riel to warn them of the potential consequences of their actions. Bruce and Riel were polite but firm. They understood the risk. The Métis Nation was not out to make an enemy of the Company, but the North-West was theirs and they would not be pushed out. Riel assured the council that the Métis recognized its authority and was not rebelling against the queen or against the Company. Riel argued that Canada was a foreign power, so resistance against Canada was not a rebellion.

Riel’s argument, that the Métis action was not a rebellion against Canada, was sound. Canada was a foreign country. But was it a rebellion against Britain? According to British law, Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were British lands and subject to British law and rule. Under British law the actions of the Métis Nation could be considered a rebellion or at the very least as unauthorized activity.

British law did not recognize any sovereignty in the Métis Nation and recognized native title to the land as a mere property right that was only affirmed at the precise moment it was extinguished. It has always been a convenient legal argument. Britain assumed that its assertion of sovereignty legally displaced Indigenous sovereignty. This bald assertion of sovereignty, which amounts to saying “because we said so,” is the sole basis of Canada’s claims of ownership and jurisdiction. One American senator put his finger close to the reality button when, with reference to Panama, he said, “It’s ours. We stole it fair and square.”12 For the Métis Nation there was never anything fair or square about Canada’s acquisition of the North-West.

On the ground in Red River the two world views were on a collision course. Canada and Britain were cutting a deal and didn’t think they had to stoop to negotiate with the riff-raff on the ground. When the Council of Assiniboia could not dissuade Bruce and Riel from their path of resistance, they were called “malcontents who could not be reasoned with.” With classic condescension the Métis were said to have “excitable temperaments, which it was impossible to control”—meaning that the French Métis could not be persuaded to remain quiet and passive.13

After Riel’s departure the council asked Dease and Goulet, two Métis who sat on the council, to collect “the more respectable of the French community” to head to the St. Norbert camp to “procure their peaceable dispersion.”14 Goulet would have nothing to do with it. When Dease took the request as carte blanche to arm his supporters, the Council of Assiniboia quickly rescinded its order. Nevertheless, Dease rode with eighty men to La Barrière, where he squared off once again with Louis Riel.

Dease was hardly the best or an honest broker for the Council of Assiniboia in light of his attempt to overthrow it just a few short months ago. At La Barrière he argued that it was best to let McDougall in and negotiate afterwards. Riel argued that it was crucial to negotiate terms before Canada entered and took control. The issue again went to a vote, and the majority—a large majority—voted against Dease. For Dease it was a humiliating loss. He had set out for the meeting with eighty men. He returned with sixty. Twenty of his men had defected to Riel on the spot. Dease’s confrontational style succeeded in rallying even more Métis to Riel’s side. Not a man to give up, Dease approached McTavish and then Colonel Dennis, offering to go and get McDougall if they would supply the guns and ammunition for a party of fifteen. McTavish and Dennis both said no.

Meanwhile rumours ran wildly through Red River. It was said that hundreds of armed men had come from all over the country, which was a fact—the Métis were gathering and there were hundreds of them. Another rumour, not based in fact, spoke of a major battle that had been stopped in its tracks by fear of the souls of dead Métis who had risen from their graves to aid their brothers at La Barrière.

THE MÉTIS LAWS OF THE PRAIRIE AND THE RED RIVER CODE

Every effort to stop the French Métis activists had the opposite effect. Their numbers grew every day. Métis tripmen as far away as northwest Saskatchewan deserted their brigades and went to Red River when they heard of the resistance led by Riel. As they grew in size and purpose, Riel knew they needed laws. They resolved to organize not according to British or Canadian culture, but according to their own culture. They resolved to codify the Métis Laws of the Prairie, which would remain in place until supplanted by another authority. On October 30, 1869, at a large Métis assembly at La Barrière, a Red River Code was proclaimed and adopted.15

In four short months the Métis Nation had gathered its forces, evicted strangers off their lands, taken up arms, enacted their own laws and elected a Council of the Métis Senate to act as their representatives. They did all this in a democratic manner and with the support of their people. By November 1, 1869, the St. Norbert camp had over five hundred Métis in arms. All swore an oath of fidelity and to refrain from drinking alcohol. The camp was a model of discipline with everyone obeying the new laws. The Métis Nation now had an operating government.

THE MÉTIS EXPEL MCDOUGALL

Meanwhile Canada’s would-be governor was faring rather poorly. When McDougall arrived at the international border on October 30, Governor McTavish ordered him to stay put. So McDougall’s party was stuck in Pembina living in sod huts with winter fast approaching. Colonel Dennis tried to raise a party from the Scottish and English settlers to escort McDougall into the settlement, but the settlers declined, saying bluntly that they mostly agreed with their Métis friends and neighbours.

McDougall was staying at the Company post in Pembina on the Canadian side of the international border. But Riel wanted him out of the country, so on November 1 Ambroise Lépine rode to Pembina and ordered McDougall to move south of the border onto American soil. When McDougall demanded to know who sent him, he replied, “The government.” McDougall asked, “What government?” Lépine answered, “The government we made.”16

McDougall tried to laugh it off and flourished his papers, which likely looked impressive and official with signatures and seals. But Lépine proved immune to fancy props, simply saying he was there to execute Riel’s orders and McDougall would leave whether he liked it or not. At that point it seemed to have finally dawned on McDougall that he was powerless, isolated and vulnerable. His party left in such a hurry they forgot one of their horses and had to come back to beg for it. The request was cheerfully granted with a display of Métis gallantry.

McDougall had been outmanoeuvred. He was a would-be governor, not wanted by anyone, with no place to go and nothing to govern. The Métis had turned McDougall into an international joke. Everyone poked fun at his helplessness, his dreams of grandeur and even his furniture. Apparently he had packed two thrones. One was said to be finer than the throne in Ottawa. The other, hitherto unknown in Red River, was a toilet, which Pierre Falcon sweetly satirized in “The Ballad of the Trials of an Unfortunate King.” Everyone had a good laugh at McDougall’s expense. Sir John A. Macdonald laughed, and so did the American press: “A King without a Kingdom is said to be poorer than a peasant. And I can assure you that a live Governor with a full complement of officials and menials from Attorney-General down to cooks and scullions without one poor foot of territory is a spectacle sufficiently sad to move the hardest heart.”17

TAKING FORT GARRY

Rumours continued to swirl throughout the settlement. One rumour was that the Canadian Party was planning to take control of Fort Garry from the HBC. The Métis could not allow that to happen because the party in control of the Upper Fort controlled Red River. The Council of the Métis Senate and the Métis Nation’s war council authorized a detachment to capture Fort Garry and to stand guard in Winnipeg. André Nault, in command of a small Métis force, captured the fort. It was easily done; the gates were wide open with no one on guard. The Métis simply walked in and took the fort. Shortly after their arrival Nault reported that he saw the Canadian Party men approach and then retreat when they realized the Métis were in occupation.

The Métis began to patrol the settlement at night. They had guards on the roads coming in and out of Winnipeg, in Winnipeg itself and in Fort Garry. There were now an additional sixty guards, equally selected to represent St. François Xavier, St. Norbert, St. Boniface, Ste. Anne and St. Vital. The discipline and sacrifices of the Métis guards made an impression on Alexander Begg, who wrote:

Some idea may be formed of the earnestness of these French people when it is stated that at this moment some of them have been eighteen days on guard—sleeping at night on the snow with no tents or other covering except their ordinary clothes and this without the least prospect of pay—the food they eat is the only thing they get and that is furnished them by the more wealthy among their own people.18