THE ORANGE LODGE

We come now to the second battle in the war between the Canadian Party and the Métis. Louis Riel had won the first battle. The Métis had executed Thomas Scott and forced Schultz, Charlie Mair and the other leaders of the Canadian Party out of Red River. Schultz was down, but he was not out. He made the rounds in Ontario, stirring up hatred—and he did have to stir it up, because initially Ontario was quite indifferent to the affairs of Red River. Schultz and his friends had to work their own people.

They began to hold a series of indignation meetings in Ontario in early April 1870. Their first meeting resulted in resolutions to send forces to Red River and a demand that Macdonald refuse to receive the Red River delegates of those who had “robbed, imprisoned and murdered loyal Canadians.” The headline of The New Nation article reporting on the meeting read, “Schultz & Mair and their Associates Advocate Mob Law at Toronto to Lynch our Delegates.”1 The headline was accurate.

The plan was pretty basic. Schultz wanted to go back to Red River, but he needed an army to confront the Métis forces. So he raised his own army with lies, fear and the aim of revenge. He lied when he claimed his fortune had been wiped out and that his wife was a Métisse. But his lies gained him public sympathy for his financial woes, and claiming his wife was a Métisse created the illusion that he had no personal axe to grind against the Métis. The fear he spread was based on what would happen if the Fenians and the Métis, both Catholic peoples, joined forces. It was a potentially deadly combination to be sure and one that would have been offensive to the Protestant Orange Lodge. But Riel had long aligned himself and his men with Canada. There was virtually no danger that the Fenians and Métis would join forces. Schultz had an advantage in this game, though, because no one in Ontario knew anything about Red River. No one would fact-check Schultz about his lies or the fear he spread. He peddled revenge for the execution of Thomas Scott.

At indignation meetings throughout Ontario, Schultz and Mair called for Riel’s head again and again. They made a saint of Thomas Scott. Schultz in particular had a dramatic bent. He liked props. He’d wave a piece of rope he claimed had been used to bind Scott’s wrists. He even carried a small bottle said to contain Scott’s blood. Schultz and Mair were very good at whipping up the crowds with anti-Riel and anti-Métis sentiments. Everywhere they went they passed the same resolutions and sent them on to Ottawa.

The Canadian Party, especially Schultz, wanted the riches of the North-West, and the Métis Nation was the only real obstacle to obtaining those riches. The Métis were a serious obstacle because they were a large, cohesive group, they were determined to protect their lands, and they were armed and organized. The only way to eliminate the Métis obstacle was for the Canadian Party to raise its own army. The men for this army were to be found in the Orange Lodges in Ontario.

The full name of the Orange Lodge was the Loyal Orange Association of British America. It was a society characterized by its penchant for violence and secrecy. Its members viewed Catholics and French as disloyal and culturally inferior. By 1860 there were over twenty lodges in Toronto alone. It is estimated that fully one-third of all Protestant men over twenty-one in Canada were members of the Orange Lodge.2 In the late nineteenth century, Toronto was known as the “Belfast of Canada,” a reference to the Orange influences in municipal government. The Orange Lodge permeated all levels of the English-Canadian establishment.3

Schultz offered the Orange Lodge what it wanted most: the blood of Papists, Frenchmen and the Métis. Papists and the French were the usual targets for the Orange Lodge. The Métis Nation in the North-West, previously unknown to the Orangemen in Ontario, was a new target. But Schultz and Mair needed something to activate their rage. Revenge was the perfect tool, and for Schultz’s purposes, it was not a dish best served cold. Schultz and Mair needed their revenge to burn hot. Revenge for the execution of Thomas Scott turned out to be just the ticket.

The Orange Lodge made no secret of its intention to go to Red River on a mission of vengeance for the death of Thomas Scott. The Lodges passed dozens of resolutions similar to the following:

Whereas Brother Thomas Scott, a member of our Order was cruelly murdered by the enemies of our Queen, country and religion, therefore be it resolved that . . . we, the members of L.O.L. No. 404 call upon the Government to avenge his death, pledging ourselves to assist in rescuing Red River Territory from those who have turned it over to Popery, and bring to justice the murderers of our countrymen.4

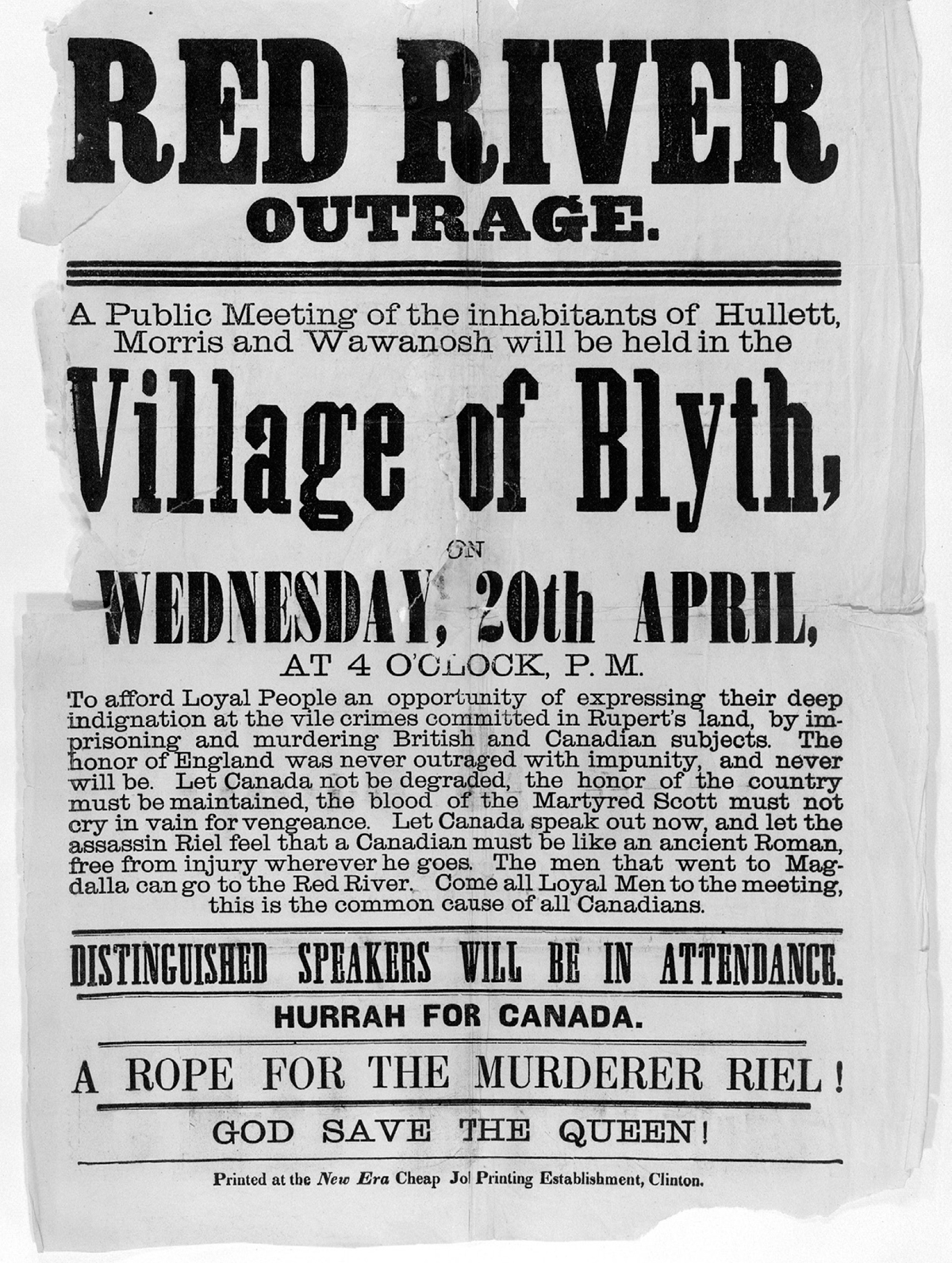

An Orange Lodge poster calling for a rope for Riel (Manitoba Archives P7262A/6)

By August 1870 the city of Toronto and villages throughout southern Ontario were full of inflammatory notices that read: “Shall French Rebels Rule Our Dominion?”, “Orangemen, is Brother Scott Forgotten Already?” and “Men of Ontario, Shall Scott’s Blood Cry in Vain for Vengeance?”5

The Canadian Party continued to make the rounds in Ontario. At first they thought they would need an amnesty for their own participation in the killings of John Hugh Sutherland and Norbert Parisien. And that should have been the case. But they soon realized that Ontarians had not even heard about Parisien, which was perfect for them. They didn’t have to defend their responsibility for his death. They could continue to raise a vendetta against the Métis for the death of Thomas Scott.

The Ontario press, especially The Globe in Toronto, loved it. Schultz and Mair had always had the sympathy of the Ontario press. Nothing had changed there. The press in Quebec, while not sympathetic to the Orange outrage, was also not much inclined to inquire too deeply into what was happening in Red River. The New Nation was the only paper to challenge the obsession of the Ontario press with avenging Thomas Scott: “Three lives have been lost . . . Yet those very men who have been lionized and lauded by the Globe and its partisans, are the primary murderers of Sutherland, Parisien and Scott.”6

THE CANADIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

There was no public announcement about why Canada and Great Britain were sending the army to Red River. The silence allowed some to think the force was symbolic and others to think the purpose was punitive. The Orange Lodge insisted that the purpose was to implement what they called “justice” in Red River and turned it into an election issue. At least in part because of the Orange votes, the Conservative government in Ontario fell. Thereafter Macdonald made soft noises about the peaceful mission of the Expeditionary Force but stayed silent when Orange Lodge members enlisted with their well-known goal of vengeance.

Two-thirds of the 1,051 non-commissioned officers and men in the Expeditionary Force bound for Red River came from the Orange Lodges of Ontario. They freely admitted that the desire to avenge the death of Scott was one of their inducements to enlist. Some admitted that “they had taken a vow before leaving home to pay off all scores by shooting down any Frenchman that was in any way connected with that event.”7

What happened next was entirely foreseeable. Sir John A. Macdonald knowingly sent into Red River an Expeditionary Force embedded with the dogs of war. These angry men from the Orange Lodges of Ontario would rape and assault, pillage and then plunder Red River. Once let out, the dogs were not easily contained. Macdonald’s correspondence provides evidence of his intentions and his motive. Before the Expeditionary Force left for Red River, Macdonald wrote that the Métis were “wild people,” “miserable” and “impulsive half-breeds.”8 He wanted the Métis to be “put down,” “kept down” and “kept quiet.”9

As he wrote those sentences, Macdonald was actively trying to engage Britain to send a force to Red River, and he was planning the commission of boats to ship an army out there. We know that he intended to use force because he wrote of using a “strong hand,” and that he contemplated the use of excessive force because he would happily give the head of his army “the chance and glory and the risk of the scalping knife.”10 So, Macdonald’s intention to use force against the Métis was clear, and these statements were all made before Thomas Scott was executed and before the Expeditionary Force was established. There is no indication that Macdonald ever backed away from these statements, and the facts show his intentions were fully carried out.

Sending troops didn’t make practical sense at the time. It was expensive. And by the time they set out, everything was peaceful in Red River. Although there was a sentiment that Canada had to send a force to put down the Métis rebellion, there was nothing to put down and no need for an army in the summer of 1870. Canada and the Red River negotiators had come to an agreement. Parliament and the Provisional Government in Red River had approved the terms. If the political problem in Red River had been solved, why send in the army? The reason is that solving the political problem in Red River didn’t solve the political problem Schultz had created for Macdonald in Ontario. The many voters in Ontario far outweighed the few new voters in Manitoba.

The evidence suggests that Canada had always planned to take over the North-West by force. We need only recall the shipment of rifles and ammunition sent out to Red River with the would-be Lieutenant-Governor McDougall in 1869 and the survey party bearing military titles and packing uniforms. Everyone wanted an armed force in Red River. McDougall, Donald Smith, the prime minister, and the Anglican bishop of Rupert’s Land all wanted troops.

Only Britain was reluctant. It had experience with native unrest in its colonies and knew the dangers of sending in an army to “put down” the natives. Britain was not eager to send an armed force against the Métis, and they didn’t want to rile the Americans either. The American Civil War had just ended, and there were a lot of American men roaming around that could quickly be gathered into an army. Britain didn’t want to put troops on the U.S. doorstep.

But Macdonald was committed to the idea of sending an armed force to Red River. By the end of January 1870, he had boats ready to transport the troops across the Great Lakes. By February his correspondence to London was more strident. A Canadian Expeditionary Force was to set sail as soon as the Manitoba Act received royal assent on May 12, 1870. Great Britain, bending to Macdonald’s insistence, agreed to send its own men, but only for the journey into Red River. Britain was the delivery agent for Macdonald’s dogs of war. The Expeditionary Force received its standing orders on May 14, and by May 25 Wolseley’s force was at the western edge of Lake Superior. There they waited until the Manitoba Act came into effect on July 15. The force left the next day, overland, for Red River. They went overland because the United States refused to allow a Canadian army or its equipment passage over American soil.

On the old voyageur route, the troops complained about the weather, mosquitoes, road conditions, and the difficulties of lugging cannon and equipment 435 miles from Lake Superior to Red River. There were still many old voyageurs in Red River. One can almost hear them laughing when they heard about the complaints.

Wolseley was supposed to be on an errand of peace. But immediately upon arrival in Red River on August 24, he dropped even the pretence of a peaceful mission. Thereafter he spoke of protecting the settlement from the tyranny of the “banditti.” Wolseley was in outright defiance of his orders to be a force for peace. He even published stories about his activities. He refused to discipline his men or to use his power and influence to deter the violence perpetrated by his men. In a weird revival of the Hudson’s Bay Company authority, he asked Donald Smith to become the acting head of state until Lieutenant-Governor Adams George Archibald arrived. Smith claimed that he refused to issue warrants against Riel and Lépine during his twelve-day “rule.” But Lieutenant-Governor Archibald stated, under oath, that warrants for the arrest of Riel, Lépine and O’Donoghue were issued and in the hands of constables before his arrival.11

The volunteers were frustrated and angry because they could not lay their hands on Riel and Lépine, who had fled to the United States. That anger never abated, and the troops went on a vicious rampage that would last two and a half years. The prime minister, so anxious to use force to put down, after the fact, what had essentially been a non-violent political movement, did nothing to stop the violence.

FEAR

There were over ten thousand people in Red River when the Expeditionary Force arrived. Eight thousand were fairly evenly split between English and French Métis. But the arrival of the troops, just over one thousand men, established the emotion that was to dominate the population for the next two and a half years—fear.

On August 24, 1870, the British Imperial Force escorted the first wave of the men into Red River. The civilian authority, Lieutenant-Governor Archibald, arrived on September 2. The British troops shipped out on September 3, and Schultz arrived on September 6.

The Expeditionary Force, officially under the command of Colonel Wolseley, was readily available to carry out the revenge envisioned by the Orange Lodge, and for that purpose it was under the virtually unopposed command of Schultz. One of Schultz’s supporters summed up their goal: “The pacification we want is extermination. We shall never be satisfied till we have driven the French half-breeds out of the country.”12

On the first day, Wolseley claimed to have “captured” Fort Garry, which in point of fact was unoccupied. His Expeditionary Force looted the stores of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the house Riel had used as a headquarters. They shot a horse out from under Father Kavanagh, injuring the priest from the White Horse Plain. Wolseley also claimed to have captured two “spies.” In reality his men assaulted and then imprisoned two elderly Métis men, members of the Provisional Council, who were peacefully wending their way home. One was sixty-year-old Pierre Poitras, a famous buffalo hunter, a nephew of Cuthbert Grant, and a man who had fought at the Battle of the Grand Coteau in 1851. Poitras was seriously injured in the attack. That is how the Red River occupation began.13

The Métis were acting on fear even before the Expeditionary Force arrived. As word of their violent intentions spread throughout Red River, some Métis left for the Plains. Within days of the troops’ arrival, many more Métis quietly gathered their families and slipped out of Red River.14 Those who stayed quickly became immobilized and demoralized: “Our people cannot visit Winnipeg without being insulted, if not personally abused, by the soldier mob. They defy all law and authority, civil and military.”15

Forced to live under an occupying army hell-bent on revenge, the Métis began to avoid Fort Garry. Social connections with relatives and friends in other parishes were severed. English Red River and French Red River became completely isolated from each other. For the French Métis there were serious economic consequences. Fort Garry was the trade centre and the main store. For the majority of the French population, trade was disrupted and everyday purchases at the fort became difficult if not impossible: “I do not feel safe. Certainly I would not take any money and walk between Winnipeg and Fort Garry after ten o’clock . . . I do not believe that any village was ever in so short a time so thoroughly demoralized as Winnipeg, since our arrival—for Riel, with all his faults—kept up an excellent police force.”16

Whether they had business or family there, everyone who had even been remotely connected to Riel and the Métis cause was now afraid to “cross the river.”17 Two years later it was still not safe to cross the river.18

Most of the former leaders of Red River were gone. French Métis leaders such as Riel, Nault and Lépine were living in exile in the United States. The English leaders—Ross, Begg and Bannatyne—who had worked so hard to bring the people of Red River together in order to negotiate with Canada found good reason to absent themselves from Red River. The absence of leaders meant that the population had to fend for itself. Chaos was the result. The young Métis men tried to stand their ground and fight back. There were many brawls on the streets between the volunteers and young Métis. As the volunteers became increasingly violent, civil society, safety, and law and order for the French, the Catholic and especially the Métis became non-existent.

Métis women hid in their parishes and at home with their children and their elders. But nowhere was safe in the colony. While most Métis were afraid to cross the river into Fort Garry, that didn’t stop the troops from crossing over into the Métis parishes. Soldier vigilante squads began to raid Métis homes.19 No one was safe, not farmers in their fields, not women in their kitchens, not people trying to purchase goods at the fort and not those on their way to and from church.

Schultz and the Canadian Party published their intentions and broadcast them throughout the town. They took control of the press, and the Métis were not the only ones who objected. “The man [Schultz] who encourages lawlessness in a soldier . . . is not only a public enemy but a scoundrel of the deepest dye. There are such men in Canada today, and unfortunately they have control of the columns of newspapers.”20 Schultz and his men disabled the presses of The New Nation, the only newspaper unsympathetic to their goals. They invaded the editor’s home and whipped him at gunpoint. That same day the Telegraph reported, “[A]lready their vigorous and not unnatural detestation of Riel, and those connected with him, has commenced to work . . . It is very probable that some rough-and-tumble work will take place here, for a Nemesis is stalking abroad here, and the friends of Riel are in a perilous state”21

Members of the Provisional Government and the Métis guards were the “friends of Riel” and the particular targets. Thomas Bunn would likely never have described himself as a friend of Riel. Still, he had agreed to act on the Provisional Government and had worked hard to enable the negotiations with Canada. Placards with a picture of a hanging man accompanied by a statement that this was the proper fate of Thomas Bunn were posted about town. They threatened to tar and feather him.22

The soldiers rarely resorted to arrest and imprisonment, likely because that was an official action with authorized supervision. They were not interested in that. “Disorder reigns in the town and in the vicinity since the arrival of the troops . . . and nobody intervenes . . . Colonel Wolseley says that he did not come here to act as a policeman.”23

The Expeditionary Force did exactly the opposite of what the Métis did. Except for the execution of Thomas Scott, there were few incidents of violence perpetrated by the Métis during the period when the Provisional Government was in power. They certainly did capture and confine.24 They did not engage in random acts of revenge and violence. But the Expeditionary Force did.25

The press announced that the soldiers planned on “burning the houses of some obnoxious people” and they did. They burned the house James Ross was building and the home of Maurice Lowman, a Métis supporter.26 Soldiers dragged Alfred Scott, one of the negotiators sent to Ottawa, through the mud by his heels. A dozen soldiers seized Landry, tied a rope around his neck and dragged him. He was saved only by the actions of Romain Nault and his son, and for his pains Nault was also assaulted. The soldiers were clear about why they were assaulting these men. It was revenge for Thomas Scott.

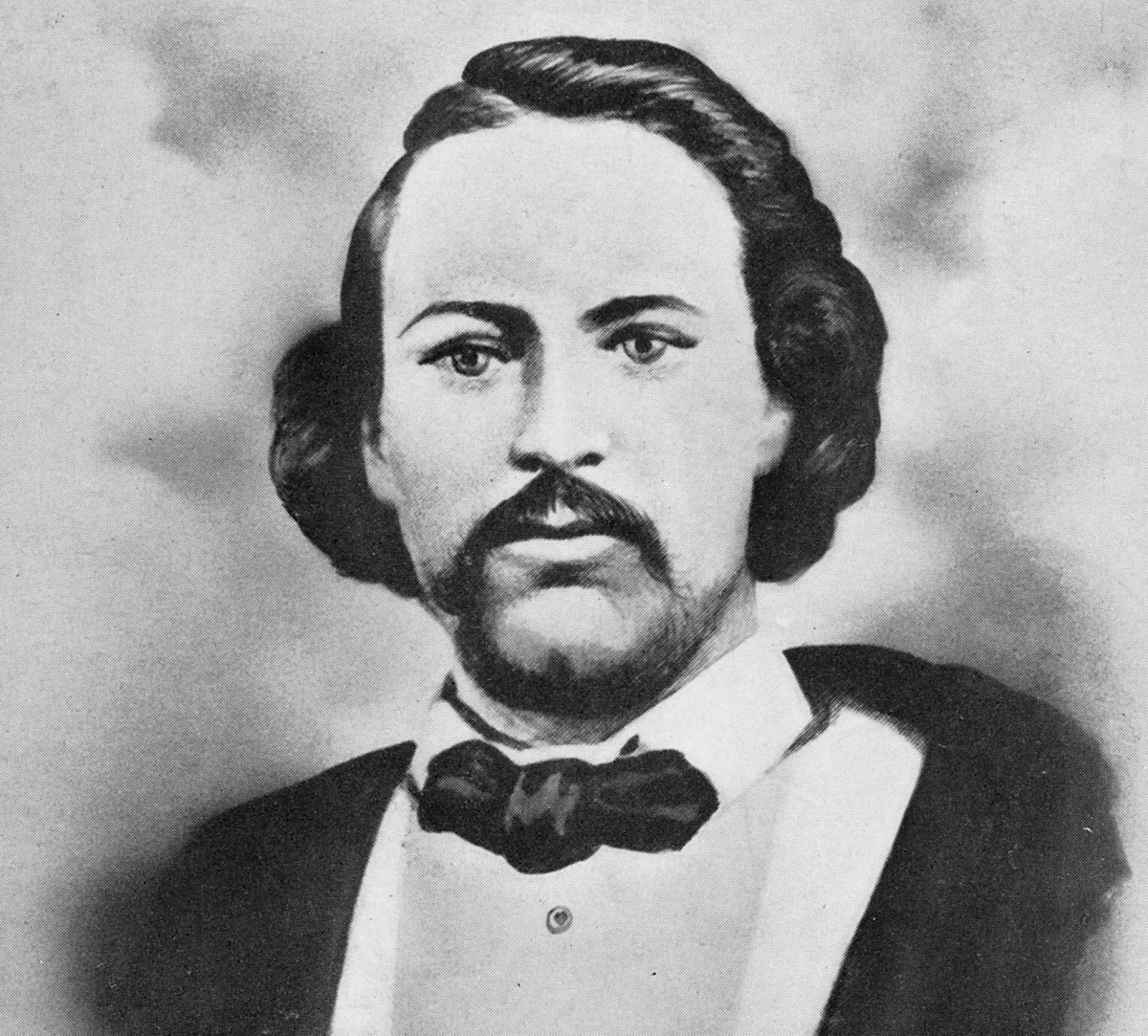

ELZÉAR GOULET

Elzéar Goulet was the first Métis man to die at the hands of the Expeditionary Force. He was murdered on September 13, 1870. Through both birth and marriage, Goulet was connected with the leading families of Red River.27 He was one of the leaders of the Provisional Government and he served on the Scott trial. Schultz’s father-in-law, James Farquharson, and three members of the Expeditionary Force were identified as the men responsible for Goulet’s death. They chased Goulet into the river and pelted him with stones until he sank. His body was recovered the next day.

Judge Francis Johnson reported to the lieutenant-governor that there was insufficient evidence to prefer a charge of murder. The British Colonial Office was decidedly not of the same opinion and was not shy about criticizing Johnson for diminishing a “felonious intent to kill” to mere “drunken mischief.”28 The office noted that any man must be horribly frightened to take to the river and didn’t accept drunkenness as an excuse for the soldiers’ murderous actions. The British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Kimberley, certainly thought there was material enough for a trial and wanted a prosecution to take place: “[I]f no evidence is forthcoming which would justify a conviction of any offence known to the law still the Govt will have done all in their power to vindicate the administration of justice and accordingly I am of opinion that legal proceedings should be taken, as suggested by the law Officers.”29

Elzéar Goulet (Société Historique de Saint-Boniface 03598)

But Judge Johnson refused to issue warrants against men who were members of the Expeditionary Force. It would cause a mutiny and a riot. The volunteers believed that Schultz had brought them to Red River to kill the men who were responsible for Scott’s death. Elzéar Goulet was one of the men they wanted dead, and they were unrepentant. Schultz’s order, which now governed the settlement, was vengeance, and vengeance has no room for justice. No one was ever charged for Goulet’s murder.

Goulet’s funeral was the first opportunity for the Métis to gather in public since the Expeditionary Force had arrived. They came from far and wide to pay their respects. Riel and Lépine came back from their exile in the United States to attend prayers, though they didn’t dare appear at the funeral. Despite the personal risk they could not let their friend and brother go without saying goodbye. It was a solemn and sad affair. Prayers were whispered throughout the evening. The Métis Nation shed many tears for the loss of their good man.

Men were assaulted if they spoke publicly or voted in a manner Schultz didn’t like. Frederick Bird, a member of Manitoba’s first legislative assembly representing Portage la Prairie, was kicked and thrown into the mud because supporters of Schultz didn’t like the way he voted. Reverend James Tanner was killed after leaving a political meeting at Poplar Point. James Ross and other Métis men who left moments later were attacked with clubs, stones and snowballs. It took an exceptionally brave man to attend a public political meeting, to vote or to speak up. The Métis held their own meetings in secret.

Archibald may have carried the title of lieutenant-governor, but he did nothing, perhaps could do nothing, to restrain the wild troops, who at this point outnumbered the population of the town. According to the U.S. consul, Archibald was a virtual prisoner of the volunteers. Archibald may not have been able to stop the pogrom, but he did what he could. He offered the shelter of his home to Edmund Turner (one of Thomas Scott’s guards and a witness at his trial) when the soldiers chased and threatened him—an act that did not endear him to the Expeditionary Force, Schultz and the Canadian Party.30 The U.S. consul thought they were beginning to secretly plot the expulsion of Lieutenant-Governor Archibald.

The sheer brutality and volume of assaults was shocking in a community that had seen nothing of the kind before. Initially many people thought the newspaper accounts were exaggerated, but they weren’t. David Tait and two companions were found half-dead. Louis (Henri) Hibbert, a Métis winterer who had recently arrived in Red River, was beaten with belts so savagely that an eyewitness was sickened by the brutality of the attack. Hibbert would have been killed if two women had not intervened. The witness, a man recently arrived from Ontario, reported that he had not really believed the violence was so bad until he saw it with his own eyes. The Canadian Party and the Hudson’s Bay Company shrugged it off. The general thought seemed to be that the Métis should not give vent to “Vive mon Nation!” or “La gloire de tous ces Bois-brûlé” in public.31

It took six weeks for The St. Paul Daily Pioneer to put a name to the violence. This was the North-West and it was no stranger to violence. For the St. Paul paper to name it a “reign of terror” so quickly gives an indication of the level of violence in Red River. The St. Paul Daily Pioneer wrote that the troops intended “to drive out by threats or actual violence” all the French Métis.32

Soldier vigilante squads roamed throughout the settlement, and Schultz’s father-in-law, Farquharson, ran one of them. He was implicated in the murder of Elzéar Goulet, and he brutally assaulted one of Riel’s most brilliant cavalry officers, Jean Cyr. In December 1871, Farquharson and a gang of men invaded the Riel home. They threatened Riel’s mother and sister at gunpoint, demanding to know where Louis was. They swore they would kill Riel. When the Métis heard about it, they were outraged and sent a petition to the lieutenant-governor.33 They wanted the men who had invaded the Riel house punished.

But no one was punished for any of the violence. The Métis thought it was because Macdonald and Schultz were working in collusion. “Collusion” may be too strong a word. It suggests a secret pact. There appears to be no evidence of such a pact. But both men and the Orange Lodge, of which Macdonald was a member, did have a common goal: ascendancy, or complete control by white, English-speaking Protestants.34 So, far from being punished for their criminal activities, some of the men involved in the reign of terror later “ascended” to high office. John Ingram attacked and beat up Joseph Dubuc. Ingram became chief of police in Winnipeg.35 Francis Cornish was involved in the invasion of the Riel home and led a gang that liberated his fellow perpetrators from jail. He became the first mayor of Winnipeg. Macdonald and Schultz may not have been acting in collusion, but they didn’t need a pact; they were acting in lockstep.

In January 1871 the soldiers murdered another member of the Provisional Government, Bob O’Lone. They also murdered François Guillemette, the man who had administered the final shot to Thomas Scott. Even living in exile in the United States provided no safety. Quite by accident Riel overheard men in Pembina discussing a plan to assassinate him, and he was able to evade them. André Nault was not as lucky and was attacked by fifteen soldiers. He attempted to run across the border to escape, but the soldiers caught him, bayonetted him and left him for dead. Nault recovered, but no one was charged with the attempted murder.36

The Métis didn’t take all this lying down. The papers regularly described fights between the soldiers and the Métis. In the spring of 1871, there was an escalation in the level of violence. The hunters were back in the settlement, and the number of Métis on the streets rose dramatically. As their numbers increased, the Métis had less inclination to avoid confrontations with the troops. The violence also increased that spring because many of the volunteers were now free of the constraints of military life. They had signed up for two-year contracts in the spring of 1869, and they were now free to continue their rampage unrestrained by officers. The minimal restraints exercised by the officers had certainly done little to stop the violence, but now even that small restraint was gone.

Women and those who tried to protect them were particularly vulnerable. Soldiers invaded Toussaint Voudrie’s home and propositioned the women in the family. Voudrie successfully evicted the men, but they returned soon after with reinforcements and Voudrie was almost beaten to death.37 Soldiers also invaded Andrew McDermot’s home, severely beat one of the servants and threatened the two daughters that their house would be burned down if they called the police.38 A dozen soldiers attacked the home of Madame Goulet. When the occupants tried to defend themselves, they too were beaten.39

When a soldier raped Marie La Rivière, his punishment consisted only of being confined to barracks. Soldiers also raped Lorette Goulet, the seventeen-year-old daughter of Elzéar Goulet. Though the men were identified to Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Peters Jarvis, the commander of the Ontario force and later an inspector in the North-West Mounted Police, his response was that rape by his soldiers was none of his business.40 No one was charged for the rapes.

Often one soldier would initiate an assault, and if he was unsuccessful, others, sometimes as many as thirty men, would pile on. When a Métis named Bourassa successfully defended himself against a volunteer who assaulted him, other soldiers jumped in and stoned and whipped him in revenge.41 On their way to see Lieutenant-Governor Archibald, Maxime Lépine, Pierre Léveillé and André Nault were threatened by a soldier. When they complained and the man was arrested, Lépine, Nault and Léveillé had to run a gauntlet of thirty angry volunteers armed with clubs.42

Le Métis ran several editorials that described the assaults as odious and brutal, and decried the violent deaths of Parisien, Tanner, Goulet, O’Lone and Guillemette, all at the hands of the people from Ontario and orangistes.43 In June 1871, when the U.S. consul, James Wickes Taylor, was attacked by the soldiers, The New York Times ran a story with the headline “Military Reign of Terror.”44 Taylor was firmly on the side of the French and Métis and wrote a report on his assault in which he said, “Outrages upon the French population are of daily occurrence—often most flagrant and cowardly in their character, and so far this incident has tended to identify me with this long-suffering population. I do not regret it.”45

Métis who had not sided with Riel because they thought him too radical, and other residents who had stood aloof during the resistance, now thought as one. The violence united the residents of the settlement together against Schultz, the orangistes and the Canadian Party.

Despite its success in murdering members of the Provisional Government and friends of Riel, the Canadian Party was still frustrated. They had not succeeded in getting Riel himself. So, they put out a $1,000 bounty on Riel’s head. Not to be outdone, Ontario upped the ante by putting a $5,000 bounty out for those concerned with the death of Scott.

Wolseley had promised that justice would be “impartially administered to all,” that there would be “equal protection” for everyone’s lives and property, that “the strictest order and discipline” would be maintained and that if anyone suffered an injury “by any individual attached to the force his grievance shall be promptly enquired into.” The Métis reminded the lieutenant-governor of that promise of justice. They petitioned and wrote letters and begged assistance in personal meetings. Nothing happened. The state in Manitoba, rapidly becoming the Orange state, made virtually no attempt to administer law and order for the protection of its Métis citizens. Riel and Lépine expressed the dismay of the Métis Nation when they wrote:

Wolseley entered the Province as an enemy . . . he gave up to pillage . . . [he] allowed to be ill-treated by his soldiers, peaceable and respectable citizens . . . The conduct of Wolseley was a real calamity. It produced its victims . . . and [the perpetrators] have lived . . . in impunity under the eye of the authorities . . . [M]urder was also left unpunished . . . The inhabitants of the settlement generally have been attacked in their persons . . . by a large number of the men belonging to the militia. And the Canadian authorities leave us to be crushed . . . These facts are supported by affidavits of honest witnesses still living. We could cite many similar facts, but these . . . show how great an injury the policy of the Government of Canada inflicts upon us . . . During the last Federal election we . . . were attacked in every possible way, even by shots . . . As for these disturbers of public order, they can all, whoever they may be, move about freely and defy the law everywhere in Winnipeg. They can show themselves even in our courts of justice . . . to laugh at our laws and show clearly in the eyes of the world that we . . . [are] plunged in the horrors of anarchy . . . The Government at Ottawa acts towards us as an enemy . . . [and] causes us to suffer frightfully and has occasioned for more than two years a public strife . . .46

The crimes cited here represent only a small portion of the pogrom. The bulk of it went unreported. But this account does provide the flavour of the early days of Canada’s reign in the North-West. The reign of terror in Red River lasted for two and a half years. Canada ignored the reign of terror when it was happening. That attitude continues. In 2018 Canada announced that the Red River Expedition of 1870 would be honoured with a new national historic designation. In the backgrounder accompanying the announcement, the minister of environment, who is responsible for Parks Canada, stated that she was “very proud” to recognize it as one of the events that “shaped our country.” She called the Red River Expedition a “vibrant symbol of Canadian identity.” Their story, said the minister, was one that tells us “who we are as a people,” one that will “inspire us towards new endeavors and adventures.”47 After the Métis Nation objected, the minister agreed to redraft the backgrounder.

The reign of terror has left a visceral anger, resentment and sense of injustice deep in the heart of the Métis Nation, specifically about the role played by Sir John A. Macdonald.

SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE REIGN OF TERROR

The Métis Nation has always cried out against the perpetrators of the crimes committed during the reign of terror. The Métis Nation knows and continues to honour the names of the victims. The Métis Nation also continues to insist that the individual who bears the primary responsibility for the crimes should be named. They say that name is Sir John A. Macdonald.

During the reign of terror there was no language to describe a deliberate campaign of crimes committed by government forces against its own people. But the language came into use shortly thereafter. Today we would call such a campaign “crimes against humanity,” defined as multiple, intentional acts committed by state actors, with the knowledge of the state, as part of a systematic attack directed against a civilian population. The description fits the reign of terror perfectly.

In Canada decisions as to whether to deploy the military, where the military is to be deployed and the appointment of senior military officers rest solely with the prime minister.48 If the prime minister chooses, he may bring the matter before Parliament. But if he does, it is merely an exercise in political discretion. So, when it came to the authorization of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the appointment of Colonel Wolseley, the decision to deploy the force to Red River and the decision not to discipline, correct or remove Wolseley, Sir John A. Macdonald made the decisions and bears the responsibility.

As prime minister, Macdonald also had a constitutional duty to protect the citizens of Canada, and that included the Métis Nation citizens in Red River. In fact he had two duties: one was to refrain from authorizing or approving crimes against his own citizens. The second duty arose once he had knowledge that such crimes were being committed. He had a duty to stop his army from continuing to commit the crimes. He failed in both duties. Macdonald knew about the violence and the deaths while they were taking place. Although he had two and a half years to stop the reign of terror, he did nothing. By wilfully remaining silent in the face of his knowledge, he approved and encouraged the crimes to continue.

It is no excuse to say that such crimes were part of the attitudes and practices of the times. Long before the phrase “crimes against humanity” was coined in the early part of the twentieth century, there was well-established international law that governments and state actors—especially those holding the highest office in the land—have an obligation to protect their citizens and not subject them to violence and death. Those responsible could not, even in those days, shelter behind their office or claim that they were enacting state policy. Common notions of justice, upheld for centuries, reveal such excuses to be flimsy and offensive. Sir John A. Macdonald cannot claim ignorance, innocence or immunity for the crimes. The Métis Nation says that for all of history Sir John A. Macdonald must answer at the bar of public sentiment for the crimes committed during the reign of terror against the Métis Nation, a people whose lives and fortunes were entrusted to his care.

THE FAILED FENIAN INVASION, 1871

Despite the horrors being perpetrated on them by the state during the reign of terror, the Red River Métis made a deliberate decision to remain loyal to Canada and proved it when Manitoba faced the threat of a Fenian invasion in the fall of 1871.

Based in the United States, the Fenians were an Irish republican organization trying to pressure Britain to withdraw from Ireland by attacking British targets in Canada. During the Red River Resistance, one of Riel’s close advisers, William O’Donoghue, was suspected of being a Fenian. After the Resistance Riel and O’Donoghue went their separate ways. But in late 1871 O’Donoghue reappeared in the United States as one of the leaders of the Fenians threatening to invade Manitoba. The past connection between the Métis and O’Donoghue raised the spectre that the Métis would support the Fenians. The possibility that Manitoba could be lost if the Métis chose to support the Fenians was not something that could be easily dismissed, especially in light of their military skills, numbers and present resentment against Canada during the reign of terror.

Rumours that the Fenians were planning an invasion into Manitoba first surfaced at the beginning of September 1871, when the U.S. consul, Taylor, brought the news to Lieutenant-Governor Archibald. On September 28 twelve Métis met at the Riel house in St. Vital.49 Louis Riel, on a clandestine visit home at the request of the Métis, set out five questions for the men to discuss:

- Does the Government fulfil sufficiently its pledges toward us?

- If it has not yet done so, have we reasons to believe that it will fulfil them honestly in the future?

- Are we sure that O’Donoghue is coming with men?

- If he is coming, what is he coming to do?

- At all events, what conduct must we follow respecting him and respecting Canada?

The answer to the first question was an unequivocal no. The reign of terror and the lack of a general amnesty made the question barely worth discussing. The second answer followed logically on the first. Judging by Canada’s actions to date, the Métis had no reason to believe Canada would honestly fulfill its pledges. Their minutes of the meeting reveal a profound disappointment in Canada “especially if one considers how the Government dodges in the presence of the Ontarian [op]pression which is contrary to us.”50 Still, they decided to delay answering the second question.

The discussion on the third question was revealing. The Métis were widely supposed to be in league with O’Donoghue and the Fenians. But not one of the Métis leaders in attendance had communicated with O’Donoghue directly, and no one knew for sure if he was even coming with the Fenians. They had all heard the rumours and believed them, but no one had any solid information. According to the rumours the Fenians were going to arrive at Pembina. If the rumours were true, then the logical conclusion was that the Fenians would use Pembina as their foothold into Manitoba and were indeed coming to attack the province.

The last question was the crucial one. What were the Métis going to do, if anything? Whatever position they decided to take—be it to side with the Fenians, stay neutral or defend the province—they wanted their Métis people to be united behind them. They knew O’Donoghue would try to drag them into it. Perhaps he even presumed their co-operation because of his support for them during the Red River Resistance and the terrors that were going on. But the Métis leaders were determined to make the decision themselves and not be pressured by O’Donoghue. They decided to send out feelers into the various Métis parishes to find out whether their people would unite unanimously in favour of the Manitoba Act they had negotiated. They had not seen the advantages of it yet, but still they advocated loyalty and moderation.

They met again on Wednesday, October 4. By that time O’Donoghue had indeed contacted them and asked them to meet him near Pembina. Baptiste Lépine and André Nault went to see what O’Donoghue wanted and how many men he had. They also wanted to see what their brother Métis around Pembina were thinking. The meeting minutes note that the Métis in the parishes were very excited by these events. No one seemed to want to actively join the Fenians, and neutrality might be the best option if they were to stay united. In light of the terror they were being subjected to, asking them to unite and act to defend the government was anything but a foregone conclusion.

The next day, October 5, thirteen Métis leaders met again in the evening, still with no particulars about O’Donoghue and the Fenians. Nault and Lépine had not yet returned from Pembina. They voted on whether to remain neutral or to act in favour of the government. They did not even consider the option of joining the Fenians. Twelve voted to stand with the Manitoba government. Only Baptiste Touron voted for neutrality, and this was directly because of the injuries he and his family had suffered at the hands of the Expeditionary Force.

On October 6 at 9:00 AM they met again to hear from Nault and Lépine, who had arrived late the night before. Nault and Lépine had met with O’Donoghue on Tuesday night (October 3), left Pembina first thing in the morning on October 4, and ridden hard for the better part of two days to bring the news. They reported that O’Donoghue claimed he had sufficient men and money, and needed the Métis “for the success of the declaration of the country’s independence.” O’Donoghue intended to take Fort Pembina on Wednesday morning.51 What Nault and Lépine did not know, because they were already on their way back, was that O’Donoghue and the Fenians did indeed take Pembina.52 News of the fort capture had not yet reached Red River when the Métis met on October 6.

Nault and Lépine then learned of the previous day’s vote of loyalty to Canada. But that was a vote of the Métis leadership. Where would the people stand? The general opinion of the leaders in attendance was that their people would have to be persuaded to stand in favour of the government. They agreed to hold meetings in their respective parishes. Some of the Métis leaders at the meeting said they would plead in favour of the government at the meetings. Others said that while they themselves were in favour of the government, they must move cautiously in advocating that position because of the angry mood of the people against Canada.

The meetings began and continued in all the French parishes over the next day. In St. Vital the answer was that the people “wish that what Riel shall say shall govern.”53 Riel’s response was to separate the injustices they were currently experiencing from the need to support the government against the Fenian invasion.54

On October 7 the leaders reconvened to bring the responses from the parishes. White Horse Plain, St. Boniface, Sainte-Anne-des-Chênes, Ste. Agathe, Pointe-Coupée, St. Norbert and St. Vital all voted in favour of the government. Each parish had also appointed captains and seconds to lead their men into battle to defend Manitoba against the Fenians. Riel wrote to Lieutenant-Governor Archibald later that same day to say that the Métis believed it their duty to respond to his call to arms that had been issued on October 4.

May it please Your Excellency: We have the honour to say to you that we . . . [will] respond to your call . . . Several companies are already organized and others are being formed . . . we, without having been enthusiastic have been devoted. As long as our services shall continue to be required, you can rely on us . . .

It was only after the Métis offered their assistance to Lieutenant-Governor Archibald that news arrived of the Fenian attack on Pembina and that it had subsequently failed. The Fenians captured Fort Pembina the morning of October 5, and the Americans recaptured it later that same day. O’Donoghue escaped into Canada but was captured by two Métis that same evening and turned over to the Americans. The news did not arrive in Red River until two days later. But Red River was still on edge. Most believed that the attack on Pembina was only a feint and that the main incursion would come from St. Joseph.

The Métis had gathered a force with some cavalry and awaited orders. It was during this period of uncertainty that Lieutenant-Governor Archibald crossed over to St. Boniface to review the Métis force and shake hands with the Métis leaders, including Louis Riel. Archibald was clearly thankful for the Métis support and stated, “If the Métis had taken a different course, I do not believe the Province would now be in our possession.”55

The danger faced by Riel and the other Métis leaders—hunted men with a price on their heads—should not be underestimated. In the absence of a general amnesty, the Métis leaders wanted assurances from the lieutenant-governor that if they appeared publicly to urge their people to stand with Canada, they would not be arrested. The lieutenant-governor assured them that “pour la circonstance actuelle” they should not be arrested.56 But arrest was the least of the worries for Métis leaders. They were more at risk of being assassinated than being arrested.

Despite the danger to their persons, they came back into Manitoba to organize the Métis to resist the Fenians. They came to the defence of Canada, a country that had forced them into exile and whose armed forces were terrorizing their people and daily trying to assassinate them. Riel in particular revealed his solid commitment to Canada. The risks they took to loyally defend Canada helps us to understand today why it hurts the Métis Nation so much to have its resistance movements labelled as rebellions.

Lieutenant-Governor Archibald appreciated the loyalty of the Métis. But he was the only one. With the gracious act of shaking the hand of Louis Riel, his days as lieutenant-governor were numbered. The Canadian Party was outraged. Schultz led a campaign to have Archibald dismissed, and he eventually succeeded in hounding him out of office. Macdonald danced to Schultz’s tune.

Archibald wrote to Macdonald warning him that Schultz was a dangerous man: “Anything in the world for self, cheat, lie, steal, friend or foe as opportunity offers—ready is he at all time.” According to Archibald, Schultz and his cronies had been “prominent in every trouble we have had.”57 The Volunteer Review, a militia magazine, called Schultz a “scoundrel of the deepest dye” and said he had done “his best to bring disgrace on the military service of his country.” Macdonald didn’t listen; he kept his alliance with Schultz and kept rewarding him.

THE BROKEN PROMISED AMNESTY

The promise of amnesty first came to Red River via Bishop Taché when he brought Governor-General John Young’s proclamation to Red River in March 1870. Young’s proclamation predated the execution of Thomas Scott, but Taché believed, and assured Riel, that an updated general amnesty was on its way.58 The List of Rights the delegates took to Ottawa stated the case for an amnesty: “that none of the Provisional government, or any of those acting under them, be in any way held liable or responsible with regard to the movement or any of the actions which led to the present negotiations.” For Ritchot the success of the negotiations depended on “being satisfied that the Royal Prerogative of Mercy would be exercised by the grant of a general amnesty.”59

Ritchot and Taché both believed an amnesty had been promised.60 They did not misunderstand the promise. It was the politicians who began to retreat from their promise. The amnesty passed back and forth between Canada and Great Britain a few times, but by August 6, 1870, Britain had made up its mind. It would not touch the question of amnesty. Canadian politicians began to deny they had ever promised an amnesty.

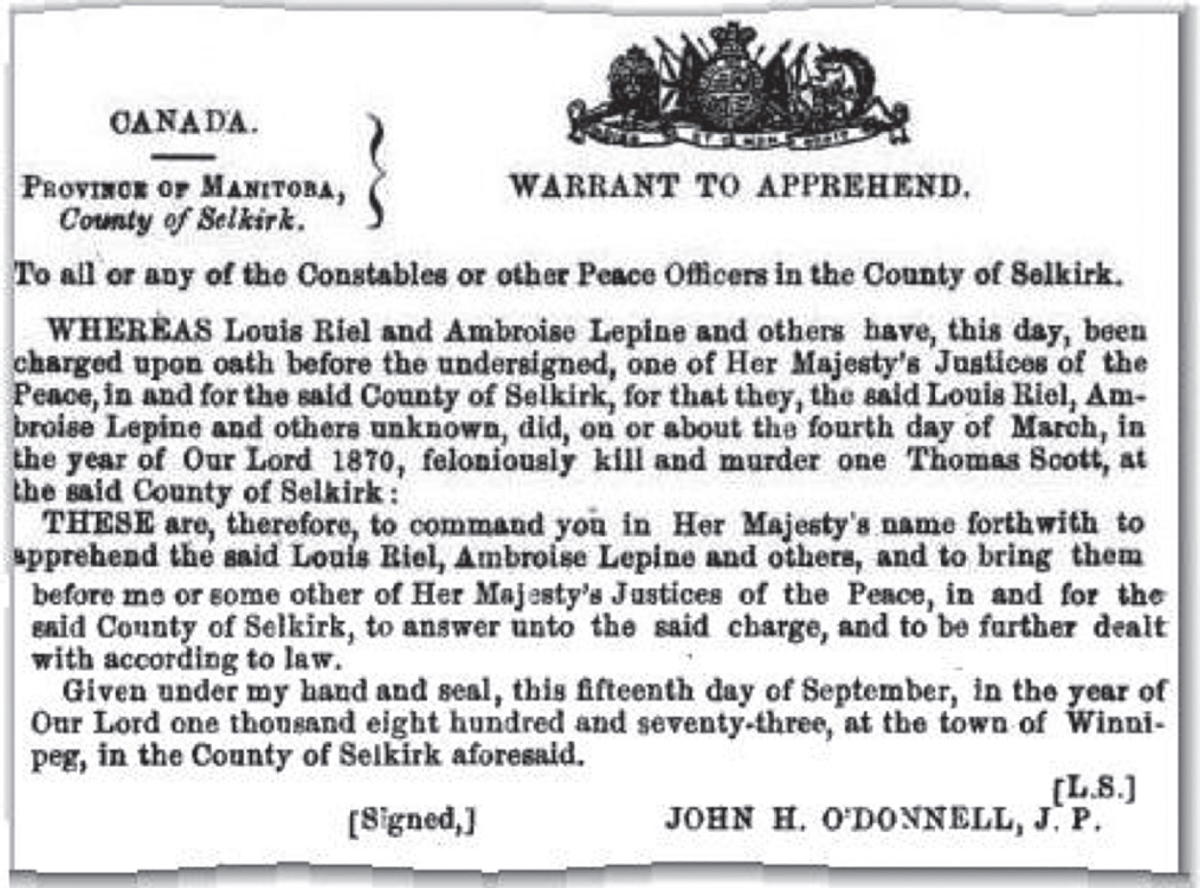

Then new warrants were issued for Riel and Lépine. Lieutenant-Governor Archibald worried about what would happen if Riel and Lépine were caught. He knew the Métis would fight hard to save them. It would be bloody. Everyone in power, the Canadian government, Bishop Taché, Father Ritchot and Lieutenant-Governor Archibald decided that the solution was for Riel and Lépine to disappear and stay away, preferably for a long time. No one in power gave a thought to what the absence of the leaders would mean for the Métis Nation in Red River.

The Métis would not let go of Riel or Lépine and kept begging them to come back. Men made constant trips to visit Riel in the United States. They kept asking for Riel’s advice. So, Riel and Lépine didn’t disappear. They couldn’t. They just kept their heads down when they came back home, which they did, often. In exile Riel questioned his own judgment. He had believed in Taché, Ritchot and Cartier, and he had wanted to believe in the amnesty. He had allowed himself to be blinded. The amnesty was not coming. Taché also felt betrayed, but he continued to push for the amnesty. Young, Macdonald and Cartier, however, were practised manipulators, and Bishop Taché was never a match for them. They played the bishop like a puppet.

Warrant for Riel and Lépine (Wikipedia Commons)

Ontario fully believed that the Catholic clergy were behind all the problems and that they were intent on making the West “another hot-bed of Jesuitism and treason.”61 Ontario considered the very idea that the Métis would bar the way to “the onward progress of British institutions and British people” unthinkable, a joke.62 It was to appease Ontario that Macdonald and Cartier refused to grant an amnesty.

The people of Red River, of all persuasions except for the Canadian Party, hated how Ontario was interfering in their local affairs. They especially hated the $5,000 bounty that Edward Blake, Ontario’s premier, had put on Riel’s head. With the passage of the Manitoba Act, 1870, Manitoba now had a legislative assembly. In 1872 it passed resolutions asking for amnesty. In 1873 Macdonald suggested an amnesty for all actions except murder. This was useless. What was needed was a general amnesty and that was not forthcoming from Macdonald’s government.

RIEL IS ELECTED TO PARLIAMENT

Despite the warrant issued for his arrest and the lack of an amnesty, Riel decided to run for a seat in Parliament. He began to campaign for election in the district of Provencher in June 1872 but was persuaded, largely by Bishop Taché, to give up his seat to Cartier, who had been defeated in his own riding. When Cartier died shortly after being elected, Riel won the by-election in October 1873. The reign of terror was mostly over by then, but there was still a bounty on Riel’s head. He remained a hunted man and it was simply impossible for him to take his seat in Parliament.

He was elected for the second time in the general election of February 1874. This time he decided to symbolically take his seat. March 30, 1874, was the first day of the new Parliament, and Riel made no secret of his presence in Ottawa. It was a public sensation. Crowds gathered outside the Parliament buildings, and there were soldiers on the grounds to keep the crowd under control. Even the governor-general’s wife, Lady Dufferin, made a special appearance at Parliament just to catch sight of the famous Riel.

Riel was there, but in disguise. Two sitting members of Parliament traditionally witnessed the oath of a new member and his signing of the register. Dr. Jean-Baptiste Romuald Fiset and Alphonse Desjardins accompanied Riel to the clerk’s office in the main corridor of the old Chamber of Commerce. Riel took up the Bible. The clerk read the oath and Riel repeated it. Then he signed his name in the register. The clerk was horrified when he saw the name Louis Riel, but before he could do anything, Desjardins and Fiset whisked Riel away and off to Montreal.

Parliament was outraged. They expelled Riel and ordered a by-election. In September of 1874 the good people of Red River promptly voted Riel right back in again. Riel appreciated the support, but it was still far too dangerous for him to take his seat.

Then, on the basis of new warrants, the Canadian Party men in Red River arrested Ambroise Lépine.

THE TRIALS OF AMBROISE LÉPINE, ANDRÉ NAULT AND ELZÉAR LAGIMODIÈRE

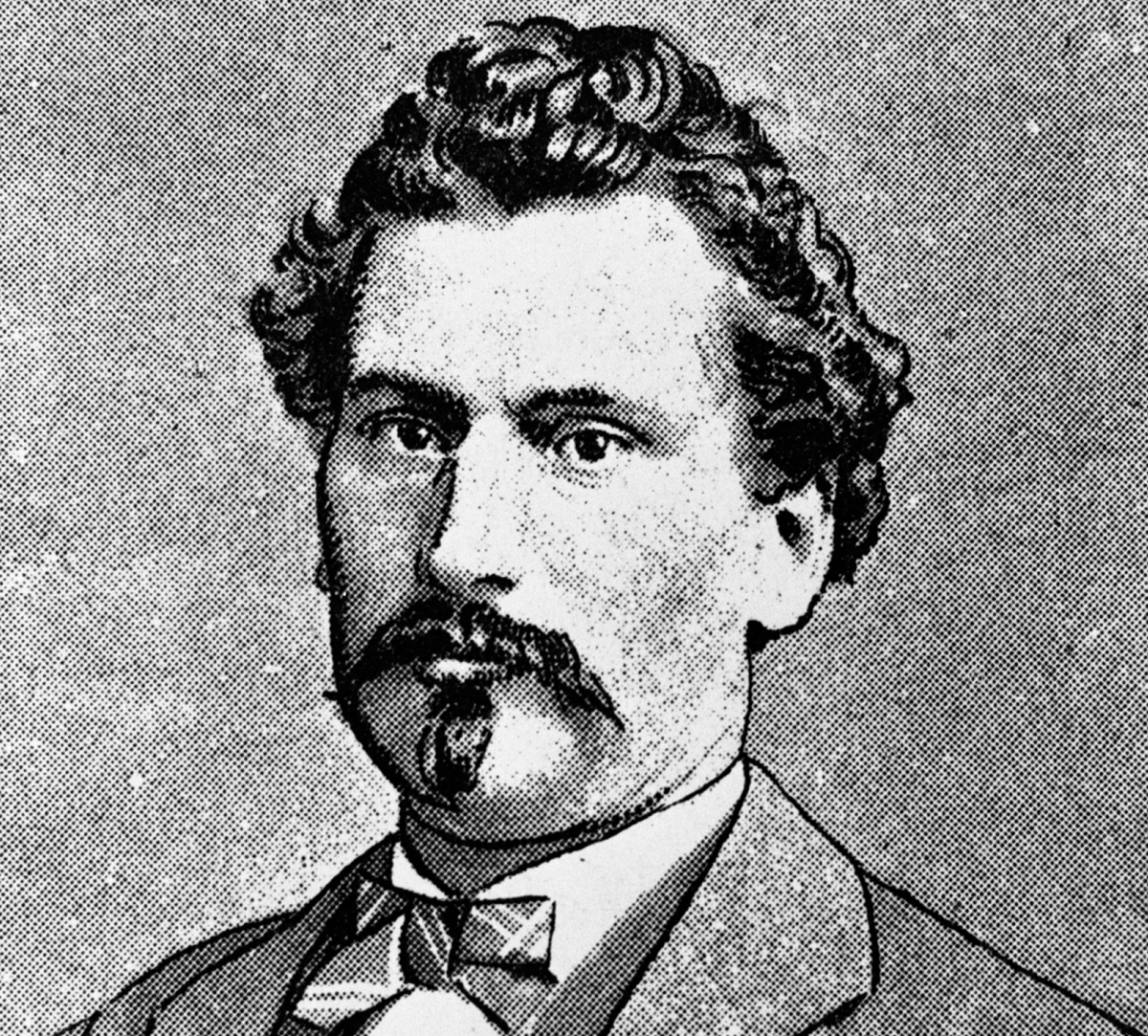

On September 17, 1873, Ambroise Lépine was arrested. Francis Cornish was the man behind the arrest. He was an Orange lawyer recently come from Ontario, and a drunk, a brawler and a vicious bigot. Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris wrote to Macdonald that “Cornish is lost to all social restraint, and his orangeism gives him a [pass] for evil.” He naturally fell in with Schultz and the Canadian Party. Cornish and his thugs invaded Riel’s mother’s home and tried several times to capture Riel. He couldn’t get his hands on Riel, but he could and did arrest Lépine. He then acted as prosecutor at the trial, and for his efforts he was awarded $400 from Ontario premier Blake’s $5,000 bounty.63

A grand jury was convened on November 12, 1873. Justice McKeagney heard the testimony, mostly in French, although he could not speak the language. The grand jury indicted Lépine, who was forced to sit in jail for six months until the new chief justice arrived in June 1874. Chief Justice Edmund Burke Wood’s appointment was a reward for helping Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberals to bring down John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government over the Pacific Scandal. On arrival Wood immediately fell in with Schultz.64

Ambroise Lépine (Glenbow Museum NA-47-29)

Wood was a scoundrel of the first order and a rude drunk. He was accused of multiple incidents of inappropriate judicial behaviour, and within six months of his appointment, the prime minister was inquiring into his financial problems. The chief justice also presided over a scheme to traffic in Métis land grants. This is the man who was the judge on the Lépine trial. The manner in which he conducted the trial was anything but impartial. So, it was no surprise that the jury found Lépine guilty. The jury recommended mercy, but Chief Justice Wood saw no reason for mercy and sentenced Lépine to hang.

The Quebec Legislative Assembly passed a unanimous motion for a pardon. Ottawa received 252 petitions with 58,568 names asking for amnesty for Lépine. The Liberal cabinet refused. Finally Governor-General Lord Dufferin stepped in over the objections of cabinet. Four days before the scheduled execution, on January 15, 1875, the Colonial Office commuted Lépine’s death sentence to two years in prison with a permanent forfeiture of political rights.

After Lépine’s trial, in November 1874, André Nault and Elzéar Lagimodière were also tried for the murder of Thomas Scott. The evidence and argument were similar to those at Lépine’s trial, but the jury simply could not agree on a verdict. Chief Justice Wood sent them back twice, demanding they come to agreement. Finally, the foreman told Wood they didn’t agree and never would. The chief justice had no choice but to declare a mistrial. Stubbornly, he held Nault and Lagimodière in prison, denying all bail applications. It was months before Chief Justice Wood permitted the attorney-general to enter a nolle prosequi, which is Latin meaning “we shall no longer prosecute.”

Parliament finally passed a motion for a full amnesty for Riel and Lépine in February 1875. The price was five years of banishment from the country. Riel accepted. Lépine refused and served out his sentence.