SOCIAL GLUE

Glue. That is what we need to find in order to understand the beginnings of the Métis Nation. Not the white glue children use to paste pictures in school. This is a search for social glue, the circumstances, values and dreams that bound individuals so tightly that they began to see themselves as a separate and distinct collective entity. The social glue that originally bound people together to create ancient cultures is often buried deep in history and predates our written accounts and historical memories. This is not the case for the culture that named itself la nouvelle nation in 1816 and now calls itself the Métis Nation. The social glue that originally bound these people together has not been lost in the mists of history. It can be traced directly to the voyageurs—not all the voyageurs, but a subset of the voyageurs, the men of the north who married First Nation women and then “went free” in the Canadian North-West with their new families. This is where we find the social glue that created the Métis Nation.

The men of the north are the voyageur fathers of the Métis Nation. They occupy a rich and romantic spot in Canadian history. They are depicted as larger than life, courageous and powerful men who braved wild animals, freezing waters, abominable weather and starvation. They boldly voyaged where no Euro-Canadians had gone before.

The voyageurs were their own best promoters. They were famous for their stories and songs. Around the campfires at night, they would boast about their horses, canoes, friends and dogs. In their songs and stories, they celebrated their exploits, tragedies and famous deeds. Storytelling was a voyageur tradition, and exaggeration played no small part in those stories. So, the wolves and bears were gigantic, vicious monsters handled with cool expertise. Storms were always hurricane force, and any loss was a tragedy of such magnitude that it moved them all to tears. No matter that they had heard all the stories before. No matter that one man claimed to be the hero in a gallant deed one night and another man claimed the same part the next night.

This story tradition was consistent with the oral traditions of other peoples around the world. The voyageurs knew what this was all about. They never confused their tales with fact, but as consummate actors they believed them passionately during the performance. Other observers, especially the English, were cynical about the voyageur storytelling tradition, thought it all childish lies and failed to appreciate the art. But for the voyageurs, the telling of their stories, and especially the performance of them, confirmed their traditions, their uniqueness and the essence of who they were. They were voyageurs. As they said, they lived hard, slept hard and ate dogs.1

The term “voyageur” originally described all the explorers, fur-traders and travellers in the North-West. Later it came to describe only the boatmen and canoeists. The mangeurs de lard or pork-eaters (named after the main food they ate) were the voyageurs plying the large boats on the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. Les hommes du nord, the northmen, paddled smaller craft into the lands northwest of the Great Lakes. It is the northmen who are of interest to this history.

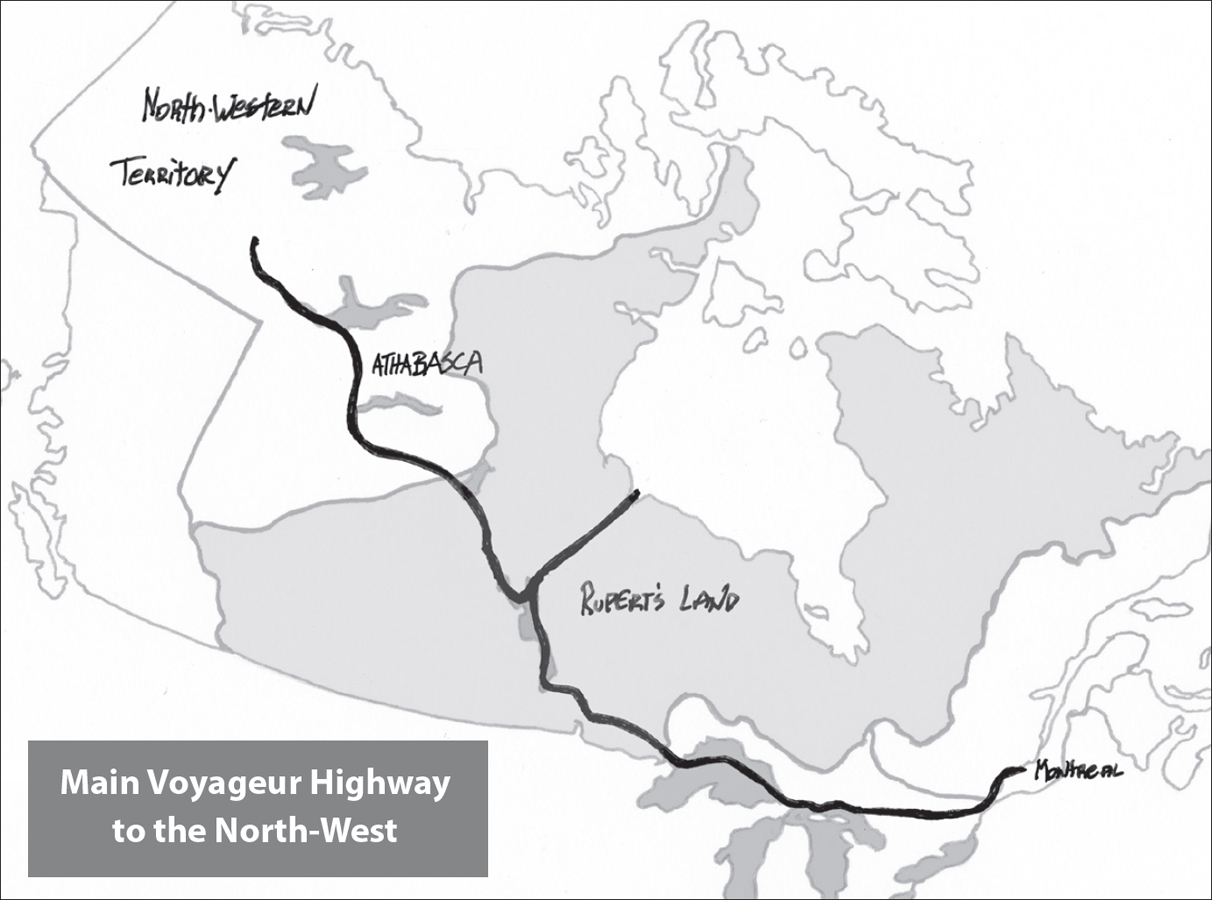

THE VOYAGEUR HIGHWAY

The routes the voyageurs travelled are called the “voyageur highway.” The voyageurs gradually pushed the highway up the St. Lawrence River and into the Great Lakes region. Until the 1780s the Great Lakes area and what is now northern Quebec and Ontario supplied many of the furs. At that time there were approximately thirty thousand people in the Great Lakes. As the voyageurs intermarried with the Great Lakes Indigenous peoples a new group of Métis, dedicated to the fur trade, began to appear. By the 1790s, the areas surrounding the upper Great Lakes had been trapped out. The Nor’Westers relocated their main trade depot to the western edge of Lake Superior. Now the North-West began on the height of land west of Lake Superior. It was on this height of land that a voyageur took a vow of loyalty to his brothers and was baptized into the elite of the voyageurs—the northmen.

The period between 1790 and 1821 was a time of great change. The War of 1812, a new American border, over-trapping in the lands surrounding the Great Lakes, and an American law prohibiting anyone other than an American citizen from trading in the United States caused a great reorganization of the peoples of the Great Lakes. In 1821 the two great rival fur trade companies merged. Since 1670 the Hudson’s Bay Company had held a British charter of incorporation. For years its employees, mostly Orkneymen, “slept by the bay”—the Hudson Bay that is—and waited for Indigenous people to bring furs to them. They moved inland to seek out furs only in response to competition from a group of Montreal traders who eagerly ventured out into the North-West. The Montreal traders were loosely organized and generally known as the North West Company or the Nor’Westers. The two companies engaged in a vicious fur-trade war, which only ended in 1821 when they were forced to merge under the name of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

These events caused trade patterns to shift and people to relocate. By 1820 those who wanted to continue the life of freedom and independence offered by the fur trade had begun to leave the Great Lakes. Métis families like the Nolins, originally from the Great Lakes, relocated to Red River.2 Some Métis men, the Sayers and Cadottes, traded in and out of the North-West, but the numbers of men who moved between the Great Lakes and the North-West dwindled.

From the 1790s until the merger in 1821, men travelled regularly from Montreal to Red River and beyond. But the merger changed everything. After the merger the new Hudson’s Bay Company shipped through Hudson Bay, and the voyageur highway no longer criss-crossed the Great Lakes. Red River began to assume more importance, and the connections between the North-West and the Great Lakes, once so solid, rapidly deteriorated. Within a few years the portages were overgrown and some could barely be found. Ships began to replace canoes, and the days when the voyageurs’ songs could be heard on the Great Lakes were ending.

Rainy Lake, on the west side of the height of land and closer to Red River, became the eastern gate of the North-West. Its original importance arose because the Athabasca brigades simply could not make it to Lake Superior and back before the winter ice made canoe travel impossible. The brigades came southeast as far as Rainy Lake, where they were met by voyageurs coming west from the Great Lakes. There they exchanged furs from Athabasca for fresh supplies. The post also served as an employment centre and a source for wild rice and fish. After the merger, Rainy Lake’s role in the Athabasca supply route diminished. Instead it became the focus of intense competition for wild rice, a critical food for the traders. Wild rice, geography, family ties and proximity to Red River kept Rainy Lake on the voyageur highway, in the North-West and within the boundaries of the Métis Nation.

The voyageur highway played a crucial role in the development of the Métis Nation. It was the artery that connected the people to the land and to each other.

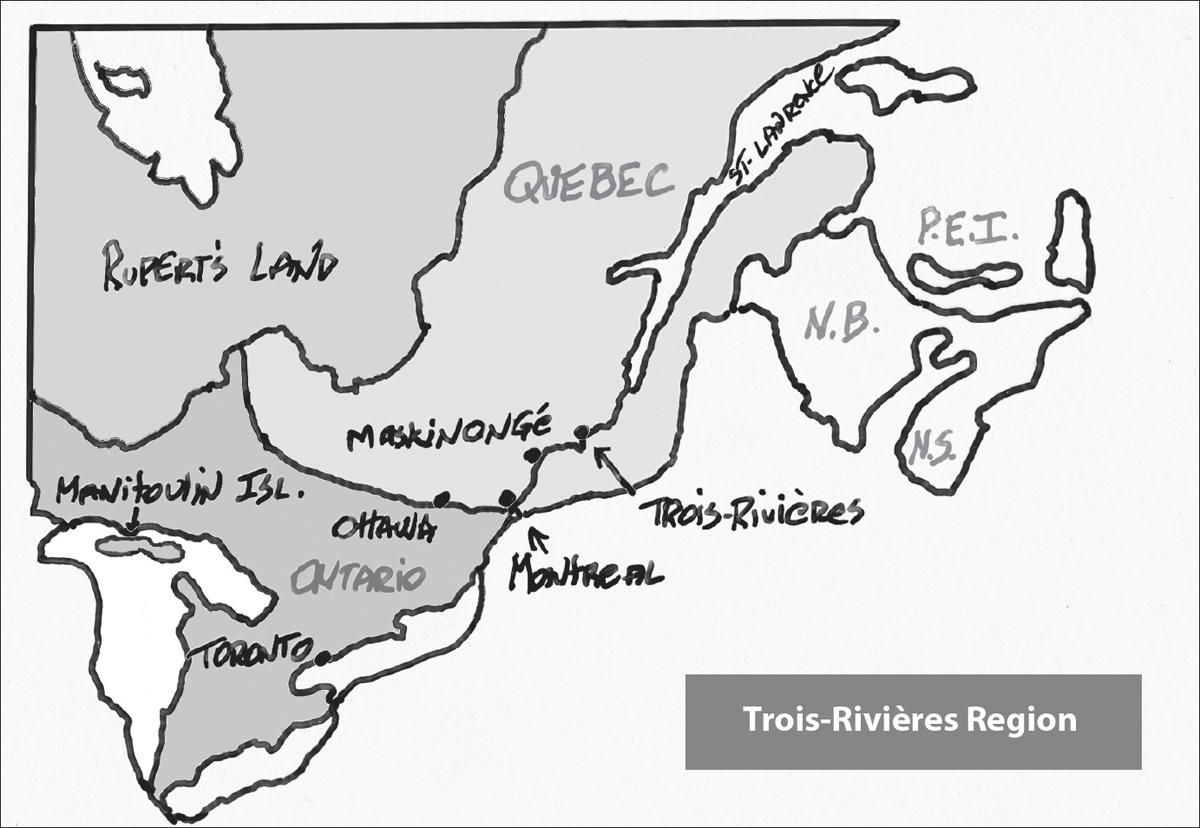

At their peak, before 1821, there were over five thousand voyageurs. They were a culture unto themselves, and although it may seem too obvious to point out, the culture was all male; there were no female voyageurs. The voyageur brotherhood was Catholic and French Canadian, mostly from the parishes between Trois-Rivières and Montreal. When they first signed up, they were usually single, young, and for the first time in their lives, away from the oversight of their parents and their priests.

The voyageurs bonded through shared adventures. Thrown together for months or years at a time, they formed the bonds of wayfarers who share celebrations and ceremonies, abundance and deprivation, hard work and danger. Washington Irving captured their bonds of brotherhood well:

The lives of the voyageurs are passed in wild and extensive rovings . . . They are generally of French descent, and inherit much of the gaiety and lightness of heart of their ancestors, being full of anecdote and song, and ever ready for the dance. They inherit, too, a fund of civility and complaisance; and, instead of that hardness and grossness which men in laborious life are apt to indulge towards each other, they are mutually obliging and accommodating; interchanging kind offices, yielding each other assistance and comfort in every emergency, and using the familiar appellations of “cousin” and “brother,” when there is in fact no relationship. Their natural good will is probably heightened by a community of adventure and hardship in their precarious and wandering life.3

Through it all they learned to appreciate and depend on each other. They competed in sport and harmonized in song. The bond thus formed was constantly reinforced by their values of sharing, equality and liberty. This bond and these values, forged by the voyageur northmen, were the social glue that enabled the creation of the Métis Nation.

THE SONGS

The voyageurs paddled into the North-West, where they met new peoples, but until they learned the Indigenous languages, they were able to speak only to their brothers. While they were initially limited in their conversation partners, their songs filled the North-West. Their stories may have been heavily embroidered, but their songs were simple. Everyone who encountered the voyageurs remembered their songs and the emotions the songs elicited. Robert Ballantyne, a Hudson’s Bay Company employee whose writing later influenced Robert Louis Stevenson, provided a vivid description of the beauty of the voyageurs’ songs:

I have seen . . . canoes sweep round a promontory suddenly, and burst upon my view; while at the same moment, the wild, romantic song of the voyageurs, as they plied their brisk paddles, struck upon my ear, and I have felt the thrilling enthusiasm caused by such a scene . . . when thirty or forty of these picturesque canoes . . . half inshrouded in the spray that flew from the bright, vermilion paddles . . . with joyful hearts . . . sang, with all the force of three hundred manly voices, one of their lively airs.4

The voyageurs sang all day. They sang to mark the timing of their paddle strokes, to lift their mood, to increase their speed, to give themselves energy and sometimes just for the sheer joy of the sound. A voyageur with a good singing voice might be hired because of his voice and paid more than other voyageurs. They even tracked their days by the number of songs they sang. A really good day was a fifty-song day.

They sang romantic French ballads, lamentations (complaintes), work songs, and their own compositions, which they called chansons de voyageur. The chansons were improvised, long and repetitive, and much influenced by the lands the voyageurs were paddling through. If there was an echo off a rock wall in a canyon or their voices carried unusually in the mist, notes, a rhyme or a word would be repeated in variations, and the voyageurs were delighted with the effect. The sound of a word or its rhyming capacity caught their ear and their fancy as much and sometimes more than the word’s actual meaning. Some songs were jazzy improvisations of the sounds of the water or the land. John Bigsby, a doctor and member of the commission established to confirm the international boundary in the early 1800s, provided a description of the voyageur improvisational tradition:

[He] sang it as only the true voyageur can do, imitating the action of the paddle, and in their high, resounding, and yet musical tones. His practised voice enabled him to give us the various swells and falls of sounds upon the waters driven about by the winds, dispersed and softened in the wide expanses, or brought close again to the ear by neighboring rocks. He finished, as is usual, with the piercing Indian shriek.5

Song tempos were fitted to the speed of the canoe or boat. The pork-eaters in the large canoes and boats on the Great Lakes with their larger paddles or oars sang slower songs, chansons à la rame. The northmen in the canots du nord sang songs with livelier tempos, and the small express canoes called for the quickest rhythms of all.

Some of the songs chronicled the history of the voyageurs and were handed down from father to son. Complaintes were composed as eulogies for those who died en voyage, or memorialized a well-known event. Sometimes the songs were survival, teaching or warning songs. One of the most famous songs, “Petit Rocher” (“O Little Rock”), told the story of Jean Cadieux, who died after defending his family from an Iroquois attack. He diverted the Iroquois while his family escaped. This part of the song may even be true. Certainly, early relations between the Iroquois and the voyageurs were not always peaceful. But the poignancy and tragic romance of the song comes in the last part. Exhausted by hunger and fear, Cadieux lay down on the rocks, too weak to call out to the search party that passed him by on the river. Days later Cadieux was found dead, lying in a grave he dug for himself. In his dead hands he held the words to “Petit Rocher.”

The voyageur songs gave satisfaction to everyone who heard them. To be sure, each passenger in the boats was a captive audience, but many commented on how the songs allowed them to endure the rain and the tedium of the long voyages, during which they had to sit for hours, unable to move even the slightest bit. Thomas Moore, the Irish poet, was entranced by the songs.

Our Voyageurs had good voices, and sung perfectly in tune together . . . I remember when we have entered, at sunset, upon one of those beautiful lakes . . . I have heard this simple air with a pleasure which the finest compositions of the first masters have never given me; and now, there is not a note of it which does not recall to my memory the dip of our oars in the St. Lawrence, the flight of our boat down the Rapids, and all those new and fanciful impressions to which my heart was alive . . .6

While the discipline of the work provided needed structure to the lives of the voyageurs, their daily working conditions were demanding and dangerous. The physical demands were beyond belief to those who witnessed their work.7 An early American treaty negotiator, James McKenney, described a voyageur day as follows:

At seven o’clock, and while the voyageurs were resting on their paddles, I inquired if they did not wish to go ashore for the night—they answered, they were fresh yet. They had been almost constantly paddling since three o’clock this morning. They make sixty strokes in a minute. This, for one hour, is three thousand six hundred: and for sixteen hours, fifty-seven thousand six hundred strokes with the paddle, and “fresh yet!” No human beings, except the Canadian French, could stand this.8

Their dress was distinctive and a unique combination of Indigenous and Canadian influences. It included a short, striped cotton shirt, a red woollen cap, a pair of deerskin leggings that went from the ankle to just above the knee and were held up by a string secured to a waist belt, an azōin (breech cloth), and deerskin moccasins without socks. Some kept their thighs bare in summer and winter. Others wore cloth trousers. In winter a blue capot made from a blanket tied with a brightly coloured ceinture fléchée (sash) completed the outfit. From the sash hung a knife, a cup and a beaded sac-à-feu (tobacco pouch).

The voyageurs loved feathers. Each northman, on getting hired, received a red feather for his cap. Northmen were distinguished from pork-eaters by the colour of their feathers. They also decorated their canoes with feathers, one in the stern and one in the bow, which was a signal that the canoe was a seasoned and worthy vessel. Before pulling into a fort, the voyageurs always stopped out of sight to tidy themselves up. They landed in their own unique style, all decked out with feathers and beads, in full song and with a merry mood.

While the voyageurs are mostly known for their canoeing, that was only their means of travelling during the good weather. These were men of the Canadian North-West, where winter held sway for six months or more. The voyageurs were not idle during those frozen months. They continued to travel by dogsled and snowshoe.

Four dogs could pull up to six hundred pounds on a narrow oak sled and travel up to seventy miles a day. The men followed on snowshoes or rode. It was a balancing act between riding, which was restful but cold, and running, which was warm but tiring. The dogs were huskies. They were left behind in summer, and Red River was known to have at least one dog hotel that housed up to one hundred dogs. The voyageurs loved to dress their horses and their dogs. Often the dogs wore fringed or embroidered saddlecloths with small bells and feathers. They also had shoes. If the rough ice cut into their paws, the dogs would lie on their backs whining and pawing, hoping the voyageurs would bring out their leather shoes, which were tied on with deerskin thongs.

The voyageurs began to create a new language. In their attempt to communicate with First Nations and to describe their unique work and situation, they created new words and embroidered their native French with First Nation words and phrases, mostly taken from Ojibwa and Cree. This is the foundation for the Métis Nation language that would later be called Michif. According to linguists, teenagers develop most new words, and Michif was no different. Its origins began with the young voyageurs.

The fact that the voyageurs were young accounts for some of the Métis traditional practices. If one can attribute a character to the voyageurs and later the Métis Nation, it is the wolf, which does actually grace one of their flags. The young voyageurs were very physical. They loved to howl, wrestle, play and hunt. They lived and travelled together like a pack. They were exuberant young male wolves, and this character fertilized the Métis culture from the beginning. The voyageur life fed an appetite for risk, exploration and novelty. In a time when there were no professional sports teams, being a voyageur was the ideal profession for a young man who liked physical challenges and wanted to travel, hang out with the guys and compete with other men. Once this lifestyle was hard-wired into their developing brains, many gave their lives to it. Despite the gruelling labour, it seems that only the rare voyageur did not love the life. One old voyageur said, “I should glory in commencing the same career again. I would spend another half-century in the same fields of enjoyment. There is no life so happy as a voyageur’s life; none so independent; no place where a man enjoys so much variety and freedom as in the Indian country.”9

Independence and freedom were their most treasured values. They sought their freedom in the wilds of the North-West, and they were willing to endure any hardship to keep their liberty. Officially they may have been servants, but when the master was a thousand miles away, the voyageurs were able to taste freedom and independence.

While outside observers uniformly thought the voyageur life was more akin to drudgery, it appealed to these young Canadiens whose future otherwise offered a different kind of drudgery, endlessly the same: working on a small family farm. In addition to the physical challenges of the voyageur life, the exciting possibility of danger and the adventure of travelling into the unknown, there were other inducements to entice a young man, including pleasures largely unavailable to a young farm boy in Quebec living under the eye of his priest: smoking, gambling, drinking, wrestling and girls.