Gilbert McMicken ran an undercover operation for Sir John A. Macdonald. During the 1860s his efforts were concentrated on the Fenian organizations in the United States. He was appointed Dominion Police commissioner in 1869, and in September 1871 he was sent to Winnipeg to establish several federal government offices. In addition to his role as Dominion Police commissioner, he served as the agent of the Dominion Lands Branch and assistant receiver-general in Manitoba. He was also appointed the immigration agent and a member of the Intercolonial Railway Commission. With these many offices to hand, he played a major role in the disposition of Métis land claims.

McMicken arrived in Red River fully supportive of the Ontario position on Riel and the Métis. His recommendations caused many of the delays in land distribution, and he was long suspected of inappropriate involvement in Métis land transactions. He inserted himself easily into the Ontario Anglo-Saxon takeover of Red River and reported to Macdonald for years on the results of his endeavours to pressure the Métis to leave. In 1873 he wrote:

The Métis are very uneasy at present. They are expressing themselves as greatly dissatisfied with the Canadian Government. Chiefly in regard to the lands not being given to them and alleging that injustice has been done to Riel. That good faith has not been kept with them in respect to him. There has been something said about a number of them having intention of moving up on the Saskatchewan and the Plains of the northwest.1

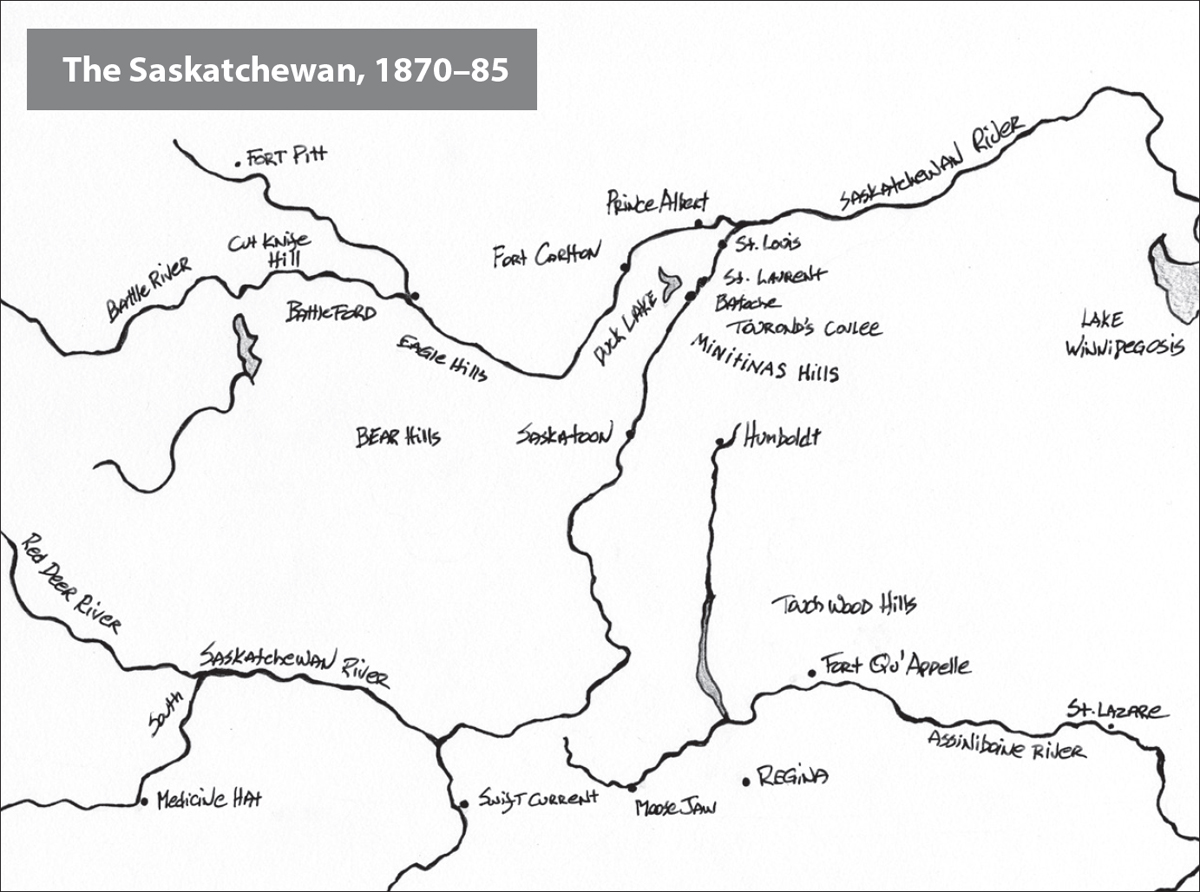

The Red River Métis diaspora began in the 1870s. Many of the people moved out onto the Plains, and from then on they would winter at Wood Mountain, Touchwood Hills, Cypress Hills, Qu’Appelle or other wintering sites in Saskatchewan, Alberta or Montana. Some of the departing Métis families went north into the boreal forest.2 Some went east to join Chatelain in the Lake of the Woods/Rainy Lake area.3 Many went to the South Saskatchewan River.

Métis settlement, Wood Mountain, 1873 (Library and Archives Canada C-081758)

The reign of terror and the broken promised amnesty forced almost one thousand Métis to flee. That was the first wave of the diaspora. It took away approximately 8 per cent of the population of Red River—no small number of people to leave the settlement. Many Métis winterers decided that Red River was now a violent place to be avoided. Their absence affected Red River’s economy. If you were Métis, especially if you were a vocal Métis nationalist, Red River in the early 1870s was a bad place to live. It wasn’t a good place to visit either. Métis leaders were in exile, and their people now started to join them—exiled from Manitoba.

Each wave of Métis emigration grew larger. The first wave was from 1871 to 1876; the second and larger wave was from 1877 to 1880. The largest wave was from 1881 to 1884. The total number who fled the violence and the land swindle was more than four thousand Métis. Many thought, at least at first, it was a temporary absence. Those who stayed faced the new civic powers in Winnipeg.

MARIE TROTTIER

Marie Trottier provides a sad early example of how Métis women would be treated in the newly installed Canadian courts. Marie was a witness in an abortion charge against a local doctor, somewhat ironically bearing the name Dr. Good. It was 1881 and she was so ill that she had to be carried into court on a stretcher. According to police testimony Trottier had been pressured by her partner to purchase an abortifacient from Dr. Good. She was seven months pregnant. After miscarrying, she began to hemorrhage. When her own doctor refused to treat her, a friend informed the police, who subsequently laid charges against Dr. Good.

Dr. Good brought seven doctors to testify that Trottier was an immoral woman. One wonders how one indigent Métis woman could have possibly known or even come into contact with seven doctors. The court never questioned this strange volume of character evidence. The judge concluded that the good doctor had not provided an abortifacient to Marie Trottier. Dr. Good would remain, in the eyes of the public, good. Marie was ordered to leave town within forty-eight hours.4

THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN

Where do you go when Red River is denied to you? That’s what the Métis now asked themselves. The need to go was apparent now. It was becoming increasingly clear that there was no place for the Métis as a nation in Red River. If they stayed, they faced a brutal, hateful regime that would not let them in and would barely let them live. Some claimed new identities as French, which allowed them to hide in the French parishes. Others became English and kept their heads down in the English parishes. Very few of those who stayed in Red River publicly retained their Métis identity. It was easier to identify as a member of the Métis Nation elsewhere.

The Saskatchewan beckoned. That is what the Métis called the lands on the South Saskatchewan River in what is now the district of Prince Albert.5 There, the Métis were far away from the hatred in Red River, and there was plenty of land. They knew this land and had hunted and lived there for decades.

Since at least the 1840s, the Métis had set up their nick-ah-wahs (wintering camps or hivernants) at Wood Mountain, Touchwood Hills and Cypress Hills. The Métis hunted in the area around what is now the city of Saskatoon throughout the 1850s. They tented in summer and built small winter cabins near the elbow of the south branch of the Saskatchewan. They traded at Fort Carlton and occasionally went to Red River.

By the late 1860s Métis wintering camps on the Saskatchewan were evolving beyond seasonal use. The camp at Petite-Ville later became better known as St. Laurent, an area that included Batoche, St. Louis, St. Laurent de Grandin and Tourond’s Coulee. In 1866 Patrice Fleury moved to Batoche with a number of Métis families from Red River. They settled at the St. Laurent settlement and began farming and freighting. In the early 1870s more Métis hunters and winterers began to settle on the South Saskatchewan.

The troubles in Red River and a smallpox epidemic in the wintering camps convinced the Métis of the need to look for more permanent residences. On December 31, 1871, a group of Métis who were wintering near the St. Laurent de Grandin mission met to choose a site for a new community.6 The decision was not made lightly or quickly. The patriarchs spoke eloquently about the need to work together, give up their reliance on the buffalo hunt and change their way of life. The Métis patriarchs knew of a good country for the people to settle in: St. Laurent.

ISIDORE DUMONT DIT AICAWPOW: [He] had been all his life a prairie hunter. He could remember when vast herds of buffalo covered the prairies from the foot of the Rocky Mountains to Fort Garry. Now they were only to be found in the Saskatchewan, and as the country got peopled the buffalo would disappear. He was an old man and could tell the young people that the decision they had come to was good, they must . . . cultivate the ground . . . He knew a tract of country between Carlton and Prince Albert which he thought would answer their purpose, it was good country, good soil, plenty of wood for building and fuel and wild hay in abundance. The grasses were good for the horses and the spot not too far from the buffalo country.

LOUISON LETENDRE DIT BATOCHE, SR: The young people could not lead the same lives as their fathers. The country is opening out to the stranger and the Métis must . . . not be crushed in the struggle for existence. What Ecapor [Isidor Dumont dit Aicawpow] said of the country was true, he knew the place and he thought it the best situation for their colony.

JEAN DUMONT DIT CHAKASTA: He agreed with all that had been spoken. The Métis must join together like brothers and work like men, he was seventy-five years old and had seen great changes in the country, but the greatest of all was at home. The buffalo would disappear . . . They will do well to til the soil and make a home for themselves amongst their friends . . . where his friends went he would follow.7

So there the Métis settled, just as they had at Red River, in rangs fronting the river, and they took up small-scale farming. By 1872 there were 250 Métis families living at St. Laurent. As word got back to Red River, more Métis arrived from St. Norbert, St. François Xavier and Baie St. Paul.

The situation on the South Saskatchewan in the 1870s was an eerie echo of Red River before the Resistance. The Hudson’s Bay Company was still a force to be reckoned with. The Company was the only store and the only source of a job or money. The Company hired Métis as freighters and still bought their pemmican. But the Company was also a new beast. It was still a fur-trading corporation, but it had other interests now, including real estate. So, when the Métis decided to establish a settlement close to one of the Company’s main posts, the chief factor’s support would have been important.

Lawrence Clarke was the chief factor for the Company in Prince Albert. Clarke was a two-faced Janus. Some people had his measure. Edgar Dewdney, the lieutenant-governor and Indian commissioner, certainly didn’t trust him, and the Qu’Appelle Métis said Clarke had “fine words and flatteries,” the better to “deceive” afterwards.8 Unfortunately, Gabriel Dumont and the Métis in St. Laurent didn’t see through Clarke until much too late.

Clarke gave his support for the Métis’ choice to settle in the vicinity. Having a permanent community providing a secure source of freighters and pemmican was a win-win for the Company. A growing Métis population would increase competition for freighting, which would allow Clarke to drive down wages. Clarke expected the new labour force would replace two-thirds of the permanent staff with short-term contract labour and thereby save the Company “by the lowest calculation two thousand Pounds sterling per annum.”9 By 1874 the Company was paying its Métis freighters and hunters only in goods at inflated cost, sometimes jacked up by as much as 100 per cent.

Clarke was also working with Donald Smith to “avoid the necessity of again trusting to French halfbreeds.”10 This was retaliation for the Métis on the La Loche brigade abandoning four boats of goods in Grand Rapids to assist their nation during the Red River Resistance. Smith and Clarke resolved to cut out the small boats, and they started to freight goods from Fort Carlton to La Loche. When the SS Northcote arrived at Carlton House in 1874, it put the La Loche brigade out of business. The Métis began to sink under the weight of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s rule.

It was worse for the freighters than the hunters. The hunters could take the meat to Red River or they could just keep it for their own food. This gave the Métis some leverage against Clarke. But the growing scarcity of the buffalo scared them all. The Métis relied on the buffalo for their major source of protein, and the Company’s northern fur-trade routes still ran on pemmican.

To make matters worse, the Company was also the law. Technically, the South Saskatchewan was governed by the North-West Council and the lieutenant-governor. But both had their headquarters a long way away in Winnipeg.11 Despite its name, the North-West Council concentrated on Indian treaty–making and otherwise paid little attention to the North-West. There was no government, and the only way of administering Canadian laws was via the Hudson’s Bay Company, which meant that Lawrence Clarke, as chief factor for Fort Carlton, was the magistrate for the South Saskatchewan. Sound familiar? It should. It was the same system that had been in place in Red River prior to the Provisional Government of 1869–70.

THE LAWS OF ST. LAURENT

Canada had asserted its sovereignty in the North-West but still had little idea of what and whom it had sovereignty over. The assertion of sovereignty meant that Canadian law was in effect in the North-West. That was the theory. On the ground there was no Canadian law. No one knew what the Canadian laws were, no one referred to them and no one enforced them. Clarke might be the official representative of Canadian law in Fort Carlton, but the Company enforced laws selectively, usually when there was a transgression against its interests.

The Métis didn’t initially see this as a problem because they had their own laws, the Laws of the Prairie. The Métis Nation Laws of the Prairie were adopted with accompanying ceremonies. The ceremonies took place at a gathering of the people on the hunts, in Red River and in St. Laurent. The leadership took an oath before a priest to act in good faith and according to good conscience. They swore on the Bible to abide by and enforce their laws. Their first codified laws were the Laws of the Hunt, and the existence of that code was well known.12 The Laws of the Prairie also included codes adopted throughout the North-West, such as the Red River Code (1869), the Qu’Appelle Code (1873) and the Laws of St. Laurent (1873).13

None of this law-making was done secretly or in defiance of Canadian law. In fact, wishing to be seen as loyal Canadians, the Métis of Qu’Appelle promptly informed Lieutenant-Governor Morris that they had formed a governing council in Qu’Appelle. They acted to fill a legal vacuum because, as far as they could see, there were no laws in place. So, they said, “We make a law, and that law is strong, as it is supported by the majority.” They sent messengers and received votes of support from “all the Métis of the North-West.”14

The Qu’Appelle Métis also expressed great anxiety about how, in making a treaty at Red River, “the people of Red River being our own people,” were maltreated. Sadly, they knew they would be treated the same. “Bright promises” were made but broken. More specifically, they noted that Schultz and Dennis, the main instigators of the reign of terror, had achieved good positions “in order to give them a chance of annoying the people of Red River.” Finally, they asked for a general pardon for Riel and the other principal men, and noted that even in 1873 it was still too dangerous in Winnipeg for Métis to appear “without being molested and ill-treated by strangers and also by soldiers.”

All of the Métis knew the Laws of the Hunt, but the codes that began to appear in 1869 were more sophisticated. With the Métis diaspora from Red River, it is quite likely that the Red River Code formed the template for the Qu’Appelle Code and the Laws of St. Laurent. George Woodcock, in his biography of Gabriel Dumont, credits the priests in St. Laurent with the idea of a governing council and the laws.15 There it is again—the belief that all ideas about governance and law, anything seen to be civilized, are to be attributed to the priests or to outsider men. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, especially the Métis history of the Laws of the Prairie, the baseline belief was that Métis were not sophisticated or civilized enough to come up with such ideas. Woodcock acknowledged that Dumont was the leader, but he seemed to assume that because Dumont did not read or write, he could not have come up with the idea for the Laws of St. Laurent.

Most people who gain experience with Indigenous people develop a deep respect for the knowledge and memories of those who live in an oral culture. Even today it is possible to witness the near-perfect recall of men and women who recite complicated agreements that had not been looked at for months or years. They remember the language and details far better than those who rely on the written word. They are tolerant of the poor memory skills of those who live in reliance on writing, flick their fingers at papers, smile, and urge that the conversation be written down—for those dependent on written words that is, not for them. They have no need to write it down. With great accuracy they remember what has been said, when, who said it and often where it can be located in the document they cannot read.

So, the idea that the Métis in Red River or Qu’Appelle or St. Laurent needed the priests to imagine a governing council or laws is condescending to say the least. By 1873 the Métis had a long history of self-government and their Laws of the Prairie. It seems more likely that Gabriel Dumont dictated the Laws of St. Laurent to the priest. Dumont was a chief captain of the hunt, charged for years with enforcing the Laws of the Hunt. He was in Red River during the Resistance, so he would have known the Red River Code. One can imagine him flicking his fingers at the papers, smiling and suggesting the priest write it down so the priest would remember. Dumont would have had no problem dictating the terms of the Laws of St. Laurent. He spoke seven languages. Memory, words and ideas—even legal ideas—were not challenging for him. Since most of the Métis, including Dumont, could not read, the oral version of the Laws of St. Laurent, spoken to the people in a large public meeting solemnized by ceremony, was far more important than a written version most had no need of and would never look at.

On March 10, 1873, the North-West Council in Winnipeg resolved that the criminal laws in force in the rest of Canada would now apply in the North-West Territories. The council appointed several justices of the peace, usually Hudson’s Bay Company officers. Lawrence Clarke was appointed for Carlton. Those justices of the peace were in office for a full year before the North-West Council acknowledged that they didn’t know the law. If the justices of the peace were ignorant of Canadian laws, it seems safe to suggest that the people would not know of them either.

This was the gap the Qu’Appelle and St. Laurent Métis were trying to fill by enacting their own laws. The St. Laurent Métis met in a public assembly on December 10, 1873, in their winter camp. They elected a council of eight with Gabriel Dumont as president. As in Red River in 1869, they took an oath to act honestly and to support their president.16 The reaction from Canadian law enforcement was anything but supportive. Lieutenant-Governor Morris was emphatic that the laws of England were in force in the North-West and there was no other council than the North-West Council, which sat in Winnipeg.

Lawrence Clarke, the chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Carlton and the local justice of the peace, clearly had his nose out of joint. He made it his mission to undermine the Laws of St. Laurent, in particular a section called “Laws for the Prairie and Hunting.” These laws regulated when the buffalo hunt would commence in April and strictly forbid anyone from leaving for the hunt before the fixed date. There were penalties for breaking these laws—fines, equipment confiscation or both. The laws were designed as a conservation measure and to protect access to the herd for everyone in the community.

The first violators of the Laws for the Prairie and Hunting were acting under the directions of a Hudson’s Bay Company employee named Peter Ballendine. In reality the order came from Lawrence Clarke. In the spring of 1875, Ballendine’s group left for the hunt before the fixed date. Gabriel Dumont reacted to the violation quickly. He led an armed party to stop Ballendine’s group and informed them that they could join the Métis hunt and the matter would be forgotten. Otherwise, there would be a penalty. Ballendine and friends were having none of it. They would not submit to the authority of the St. Laurent Métis Council. Dumont confiscated their equipment and carts, imposed a twenty-five-dollar fine and promptly left for the spring hunt.

Clarke complained to Lieutenant-Governor Morris and practically demanded a protective force. Morris sent for the North-West Mounted Police, and in August fifty Mounties arrived to investigate the Ballendine incident. Major-General Edward Selby-Smith found, contrary to rumours, that the “mighty Half-Breed hunter named Gabriel Dumont”17 had no pretension to undermine Dominion authority. The Mounties, the lieutenant-governor and the secretary of state all knew that Clarke had engineered the entire incident. But they didn’t stop Clarke from charging, trying and fining Dumont and his men.

Dumont and his council knew nothing of Clarke’s role. But the incident undermined the St. Laurent Council and also destroyed the Métis attempt to implement conservation measures to protect the buffalo. Clarke’s next move was to send out professionals to hunt buffalo. The meat was appropriated to the Company stores and then sold to their newest customers: the police detachments now stationed at Fort Carlton and Duck Lake. It was another win-win for Clarke. The loss of Métis hunting rules didn’t mean Canadian laws of conservation were put in place. It encouraged Clarke’s men to leave for the hunt earlier than the Métis. What followed for the Métis was famine.

Canada’s only act of governance was to stop Métis self-government. But there was no other government in the North-West to fill the gap. Canada was like a dog in the manger. It didn’t govern the North-West, but it would not allow the Métis to do so. This was not good governance. It was exactly what the Métis had fought about in Red River. The government was hundreds of miles away and appointed by men even farther away. The facade of governance was what it was. It didn’t exist on the ground.

The Métis who were on the North-West Council—Pascal Breland and later Pierre Delorme and James McKay—did nothing for the South Saskatchewan Métis. That’s not to say they worked against the South Saskatchewan Métis, just that their main interests were trade and Red River. The St. Laurent Métis petitioned for a representative but were considered too untamed for such civilized responsibilities.18 Even when the seat of government was transferred from Winnipeg to Battleford, there was no representative for the South Saskatchewan Métis.

With the arrival in 1878 of another fifty Métis families, St. Laurent numbered over five hundred people. More than 75 per cent of them came from Red River or the environs of Pembina and St. Joseph in North Dakota. By 1878 the Métis in the Prince Albert area numbered about twelve hundred souls with more coming every day. By 1883 there were fifteen hundred Métis on the South Saskatchewan River around St. Laurent and Duck Lake.

THE BONE PICKERS

The Métis are a stubborn lot and they held on to their life on the Plains as long as they could. They loved it. Family and friends travelled together. The food was fresh, plentiful and delicious. The camps were safe, friendly, social and filled with music and dancing. All the Métis described it as a life of beauty. For them, a life on the Plains was no hardship. They saw nothing better in a life on a farm. They held on to their life of movement as long as they could. Marie Rose Smith thought it was wonderful and said, “Oh but that was the life! Free life, camping where there was lots of green grass, fine clear water to drink, nothing to worry or bother us. No law to meddle with us . . . We always travelled with different families, whenever we would camp it would be like a nice village.”19

For a hundred years the Métis travelled throughout the North-West, trading and hunting. They were always on the move. Then one by one, the economies that had sustained their mobile lifestyle for a century began to crash in the early 1880s. It was the end of the buffalo that forever transformed their lifestyle.

The Métis said that, toward the end, some buffalo died of an infectious bacterial disease called black-leg. Hundreds of dead buffalo were seen on the Plains. In a vicious effort to starve out its Indians, U.S. soldiers burned the Plains, slaughtered buffalo and paid a bounty for each skull recovered. The disease and the American scorched-earth policy took a huge toll on the herds. The buffalo died from a combination of over-hunting, disease and deliberate slaughter. By 1882 all that was left of the magnificent herds were millions and millions of bones, hooves and horns. The Plains were covered with large, sun-bleached white bones and skulls highlighted by ebony hooves and horns lying in the midst of the skeletal remains.

For the new settlers the bones were a pain. Land had to be cleared and broken, and the bones had to be removed. The Métis did most of it. They became bone pickers. Bones were gathered onto Red River carts and hauled off to markets. The bone pickers were paid by the ton. It took one hundred buffalo skeletons to make a ton of bones. The price per ton varied over time from three to twenty-three dollars, but by the end of the nineteenth century, a ton of bones fetched about eight dollars.

The bone trade was big business. Bones were piled in ricks, some a quarter mile long and thirty feet high. Old bones became bone meal fertilizer, a pigment called bone black, and the bone in bone china, and were used to decolour sugar. Horns were made into buttons, dice or even toothbrushes. By the end of the 1880s, the business began to dwindle, but Métis were still picking buffalo bones in quantity in Canada until 1893.

A rick of buffalo bones in Saskatoon (Saskatoon Public Library LH-2823)

The bone picking removed the last physical remains of the buffalo from the Plains. And then the Plains themselves began to change. The massive herds of buffalo had played a huge role in the formation of the Plains. They fertilized the grasses, kept them nibbled down to size and packed the earth with their weight. Their presence kept the trees from encroaching. The herds were a moving ecosystem that included all the other creatures that fed off the buffalo—humans, wolves, birds and insects. When the buffalo were gone, tree saplings began to encroach, and the prairie grasses changed.

Most Métis stopped picking bones by the early 1890s. But George Fleury and his father were still gathering buffalo bones from the riverbanks around Ste. Madeleine, Manitoba, in the 1950s. The Fleurys got a hundred dollars for a wagonload of bones.20 By that time the bones were mostly buried and you couldn’t just pick them. You had to dig. The Métis say that the buffalo bones can still be found if you know where to look for them.