La Guerre Nationale ended on May 12, 1885, and the Métis fled. The combatants, the women, the children, the sick and the elderly, fearing for their lives, abandoned everything they had and headed for the Minitinas Hills south of Batoche, eighteen miles away. There they hid for three days. They had no food and many were sick or injured. Some were pregnant, including Louis Riel’s wife, Marguerite. Josephte Tourond had just given birth.

The men did their best to come to their aid. Always avoiding the soldiers who were searching the area, Gabriel Dumont scrounged for hides and took the time to make moccasins for barefoot children. He found food and blankets and distributed them among the sick, the young and the old. Louis Riel visited his wife and their two children three times.

The question for the men was whether to surrender to Middleton or to head to the United States. Most of the women wanted their sons, fathers and husbands to go to the United States. There the men would be safe and the women might be able to join them later. The women wanted their men alive, even if that meant they were far away. They didn’t want their men imprisoned and they didn’t want them executed. There was no blame for their men. Blame was reserved for the government they felt had pursued and mistreated them. But in the immediate aftermath of the war, it wasn’t a question of blame. There was bitterness and anger to swallow, but the immediate need was survival. It would be better for the men to go over the line.

The women would manage, somehow. They were not afraid to stand up for themselves when they needed to. When Marguerite Caron saw the medical officer on one of her best mares, she marched straight up to the horse, unsaddled it and took it away. The soldiers were so stunned, they didn’t say anything. In the midst of the battle and the men who were dying, Josephte Tourond gave birth in the cold and the snow. The women helping her were afraid light would attract bullets, so they only lit a fire during the final moments of the birth. After May 12 the English soldiers started looting and helped themselves to all manner of Métis goods. They stacked up their loot in a big pile. Madame Tourond searched the collection, and when she saw her own case, she tried to pick it up. Some soldiers shoved her away. But Madame Tourond spoke fluent English and took them to task for their rudeness. She demanded they hand over her case. Fortunately, an officer came to her assistance and when she told him that she had just given birth and the case contained clothes for herself and her new child, the officer kindly gave her the case and reprimanded his soldiers. It is one of the few stories that show any kindness on the part of the soldiers toward the Métis. In Edmonton the families of Garneau and Vandal, who were still in prison, were left destitute. Cree chief Papaschayo fed and cared for them.

There are many stories of wanton theft and destruction by the soldiers. Two of those stories are “The Bell of Batoche” and “Bremner’s Furs.”

THE BELL OF BATOCHE

After the Battle of Batoche, the soldiers looted the town, stealing money, furs, horses and anything they fancied. They burned and destroyed farms, houses and stores. Middleton’s soldiers stole a church bell, which ended up in Millbrook, Ontario, as a trophy of war. Quite a bit of pressure was put on the town to return the bell. But Millbrook was staunchly Orange and there was no way they were going to give back a trophy they thought they had earned. A letter to the editor of The Port Hope Evening Guide provides the attitude of the day:

What are you giving us about the bell that our Boys brought from the North-West rebellion? You say that the Bell was stole . . . The Bell was not stole. It was taken from the church where the rebels got together to arrange to shoot our brave boys—or at least that is where the priest said service and preached to them, and I don’t see much difference. Mr. Ward [the local MP] need not come out to Millbrook to coax the bell away from our Hall so as to hang it up in a Catholic steeple again. I tell you the boys ain’t going to give it up . . . I tell you we would have a Catholic bell in every Orange Lodge in Durham, and we wouldn’t have to go as far as Frog Lake for them too. It’s time us Protestants got together and put a stop to all this talk about stealing a bell from the Catholics. That kind of people have no right to have a Bell to ring in this country. I’d put a stop to it and take all their property from them and divide it among the true men of this country who are all Orangemen. You needn’t fret your gizzard about the Catholics and the Bell . . . No, sir, we mean business now, both about keeping this Bell that our boys got in the North-West and everything else about Protestantism, and you can yell the wind out of your carcass until you have none left and we will keep the Bell . . . and don’t you forget it.

No Surrender

Millbrook, July 7, 18881

The bell remained in Millbrook, first hidden in a farmer’s field, then used in the local fire hall and finally displayed in a showcase in the Legion Hall. A hundred years later, in 1990, the Saskatchewan Métis sent a letter to the Millbrook Legion requesting the return of the bell to Batoche. The response from one Millbrook Legion member was, “We got it. You tried to wreck the country and we stopped ya. And we got the bell. It’s ours. Can ya get it any plainer than that?”2 As far as Millbrook was concerned, nothing much had changed since 1888.3 But the bell has now been reacquired by the Métis Nation of Alberta.

BREMNER’S FURS

The soldiers also stole Métis furs. The loss and wanton destruction of furs was a financial disaster for the Métis. The wealth of the community didn’t come from farming. What they could grow on their farms provided subsistence food only. Their economy depended on their hunting and trapping. And since the buffalo were gone, they now trapped fur-bearers.

The soldiers destroyed any furs they found in the villages. Baptiste Boyer, one of the best trappers, had been storing his large stash of furs in his attic. The soldiers took his furs and cut them into shreds as they travelled away from Batoche. Bits and pieces of beaver, otter and mink pelts were scattered over twelve miles. Madame Fisher reported that Middleton had his men dig a large hole in front of Batoche’s store, where they buried thousands of dollars of furs.

The soldiers also helped themselves to Charles Bremner’s furs. Bremner was not one of the Métis insurgents. He had arrived from a Protestant, English-speaking Métis parish in Red River and settled on the Saskatchewan.4 While the Métis were engaged in their battles at Duck Lake and Tourond’s Coulee, the Cree had been engaged in their own battles. Many others, including those like Bremner who identified as “half-breeds” and did not support Riel and Dumont, were caught in the middle. Bremner’s family and other settlers were taken hostage by Chief Poundmaker’s Cree band and forced to move as the camp moved. Finally, on May 23, 1885, Poundmaker’s band surrendered. Throughout his captivity with Poundmaker, Bremner had carefully guarded his furs. They were worth between $5,000 and $7,000, and Poundmaker had honoured Bremner’s property.

When the soldiers captured Poundmaker’s band, they simply did not believe that Bremner’s group were captives. Bremner was a “half-breed” and to the soldiers, all such people were rebels. All were sent to Regina, where Bremner was taken into custody and charged with treason felony. When his case finally came to trial, the Crown admitted that it had no evidence against him and Bremner was discharged on his own recognizance.5 But Bremner wanted his furs. He needed them to rebuild his farm.

It was General Middleton and two men on his staff who stole some of Bremner’s furs. The rest of the furs were handed out to other officers. All of this was done under signed orders from General Middleton or Colonel Otter. The theft of Bremner’s furs is what brought Middleton down. The articles of war stated that property could only be confiscated by judicial or legislative action, and even the property of a man convicted of treason devolved to his children. Middleton was a general and he knew the law. But he testified that he thought he could do pretty much as he liked.

Bremner pressed for compensation for five long years. Eventually, a committee of inquiry found the general’s appropriation of the furs highly improper. In Parliament, Macdonald went further and said it was an illegal act that could not be defended. By this point some members of the House were out for the general’s blood. They insisted that Middleton compensate Bremner and be dismissed from his command of the military force in Canada. Finally, the House unanimously adopted the conclusions of the inquiry. It was May 16, 1890.

During the inquiry, after five years of denial, Middleton finally admitted he had ordered the furs confiscated for himself and his staff. He also promised to indemnify Bremner. But he claimed the furs had mysteriously disappeared, that he never received them and never profited from his order. Middleton resigned in July 1890, bitter about his treatment in Canada. He felt he had risked his life for Canada and that he was sacrificed for the French vote. He warned that the Canadian press would be sorry and left the country in disgrace. Once safely in England, Middleton refused to pay Bremner.

Bremner continued his fight for compensation. It took him until 1899 to get payment for his furs from Canada. Canada finally paid him because they were sick to death of the stubborn man and the only way to make him go away was to pay him for his stolen furs.

THE AFTERMATH

After Batoche many of the Métis fled south of the border. There they joined the four Métis settlements in Montana and North Dakota—St. Peter’s Mission, Lewistown, Poplar River Agency and Turtle Mountain. The Canadian government sent spies to follow them. One of the spies reported that thirty Métis from the South Saskatchewan arrived in Lewistown, Montana, in the fall of 1885 and spent the winter there. This is where Gabriel Dumont and his family landed.

According to the spies, the general feeling in Montana was against Riel, though it seems support for Riel depended on whether one was a Republican (for Riel) or a Democrat (against Riel). By the end of December 1885, the spy’s assessment was that there was no danger of a future rising from the Métis living south of the line, and if there was one, it would come from Turtle Mountain, where Gabriel Dumont intended to settle in the spring.

There are stories that Dumont tried to organize a rescue for Riel, but if that is so, it came to naught. When his wife, Madeleine, died in the spring of 1886, Dumont was at loose ends. He accepted an offer to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. Along with Annie Oakley, he performed trick shots for audiences throughout the eastern United States. He began a series of speaking engagements at meetings of French-Canadian nationalists in Quebec, where they were eager to hear about the North-West Resistance. The nationalist movement of the Métis Nation resonated with their Quebec nationalist aspirations. But Dumont was not Riel. He was not erudite like Riel and he was bitterly critical of the Church. It was not what the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal wanted to hear. They dropped him as quickly as they had picked him up. The idea of the mighty Métis hunter of the Plains who had fought for the Métis Nation was much better than the man in person. The Canadian government granted the participants in the North-West Resistance amnesty in 1886. After his brief stint as a showman and the unsuccessful attempt at public speaking, Dumont went back home to Batoche.

Some Métis men fled south of the border, some surrendered and some simply went home and waited to see whether they would be arrested or not. The Métis leaders who stayed were all arrested. Some who surrendered began to work for the soldiers. There was no rhyme or reason to how they were treated. Patrice Fleury, despite being a captain of the scouts and participating fully in the battles, was hired to take the police to Qu’Appelle and got paid well for his work. Damase Carrière suffered a broken leg during the battle of Batoche. He died after soldiers tied a rope around his neck and dragged him. The soldiers thought he was Riel.

The relationship between the Métis and the priests was irreparably damaged. The priests had used all their energy to undermine Riel and denounce the Métis recourse to arms. They had actively worked to stop Métis in other settlements from joining their brothers. Archbishop Taché had ordered Father St-Germain to Wood Mountain to quiet the Métis there. In the Métis settlement at Green Lake the priests threatened excommunication from the Church if the men went to join their brothers in arms at Batoche. The priests were both afraid of a general Métis uprising and panicked that their missions would be destroyed. They abandoned their mission at Île-à-la-Crosse in a wild fear that Riel held them responsible for his sister Sara’s death and would order the massacre of the nuns there. In fact the only action the Métis took with respect to the Church was to confine Fathers Végréville and Moulin and six nuns at Batoche. The Métis did not pillage any missions.

But they knew that the priests had been in constant communication with the soldiers during Batoche and always believed that was a betrayal. Middleton knew they were short of ammunition because of Father Végréville. When Father André told the imprisoned Métis they got what they deserved, Patrice Tourond turned on him angrily and said, “When we wanted to go to confession on the eve of the Battle of Batoche, you refused. My two brothers were killed and they had been refused that sacrament. Now that we don’t need you, you spend all your time trying to get us to confession. We don’t want you.”6

Despite the animosity, the priests tried to salvage their relationship with the rank and file Métis. Father Lacombe sent a long letter to Public Works Minister Hector Langevin, providing a character reference for many of the Métis prisoners. This was accompanied by a plea for leniency.

The priests began working with the one-man-to-blame theory. Father Lacombe blamed it all on Riel and claimed that the Métis were just “poor ignorant people”7 who had been duped and exploited by Riel. Father André provided a long deposition as to the character of the Métis in the trial of Joseph Arcand. He declared that with the exception of Gabriel Dumont, Napoléon Neault and Damase Carrière, the Métis were the poor deluded dupes of Riel.

The one-man-to-blame theory of the Métis national war continued and has persisted ever since. According to Father Lacombe, Riel forced the men to take up arms. The priests spread this story, but they knew it wasn’t true. They knew the Métis were defending their lands, their women and their children. The priests knew this was the reason the Saskatchewan Métis sent for Riel in the first place. Still, the priests claimed they pitied the poor Métis, who would never have done this if it hadn’t been for Riel. The priests saved their hostility—and there was a great deal of it—for Riel.

According to the priests Riel had usurped their role as intermediaries with God. He had manipulated the Métis and terrorized them. He was an agent of Satan. Riel alone deserved to be punished. The priests found a way of neatly framing the story: Riel was insane and therefore not responsible for his wild religious beliefs. But it was a temporary fit of insanity because Riel reconciled with Father André just before his death. It was a convenient argument that allowed the priests to sweep the participation of hundreds of Métis under the carpet.

The Métis of Batoche were not the only ones who repudiated the priests after 1885. The Métis of Green Lake accused the priests of deceiving them and provoking Riel to revolt. The Métis of Lesser Slave Lake accused Father Lacombe of selling their lands to the government. Father Moulin in Batoche complained that the Métis were not going to confession anymore. The Métis in St. Laurent stopped attending vespers or taking communion regularly. The Métis no longer introduced themselves to priests and they no longer took the priests’ political advice. The young people absorbed the new antagonism to the Church. After Batoche, the relationship between the Métis and the Church was strained almost to the breaking point. Tourond was not the only Métis who decided he no longer wanted or needed the priests or the Church.

In the first brutal days after Batoche, Riel and Dumont tried to maintain contact with their families and avoid capture at the same time. Dumont was better at this than Riel, and he was defiant. He would not surrender and he didn’t want Riel to surrender either. Middleton sent Moïse Ouellette with letters for Dumont and Riel. The letters were surrender demands. Dumont took the letter and asked what it said. The letter promised justice, Ouellette said, justice that would be granted in exchange for Dumont’s surrender. Dumont didn’t believe in that kind of justice. Justice in the hands of Canada meant one thing only: death at the end of a rope. He continued to evade the search parties. Father André basically laughed when the Mounties asked him where Dumont was: “You are looking for Gabriel? Well, you are wasting your time, there isn’t a blade of grass on the prairie he does not know.”8 Father André was right. No soldier had the skills or knew the land well enough to find Dumont. Dumont continued to search for Louis. He remained defiant, saying, “I will not lay down my arms—I will fight forever . . . never to be taken alive . . . I will not surrender, but I will keep searching for Riel—not to make him surrender, but escape. If I find him before the law does, I won’t let him surrender.”

Riel had different ideas. Unlike Dumont, Riel had already tasted the bitterness of exile in the United States. He knew exactly what it would be like. He would always be looking over his shoulder for the next attack. This time there would be no amnesty, no way to quietly visit his family in St. Vital. He would have no way of making money and no supporters. Riel knew they wanted him more than any of the others. Perhaps if he surrendered, they would be lenient with the men. Maybe the Métis would have a chance to get some justice if he could present their case. Maybe they would be happy with his head.

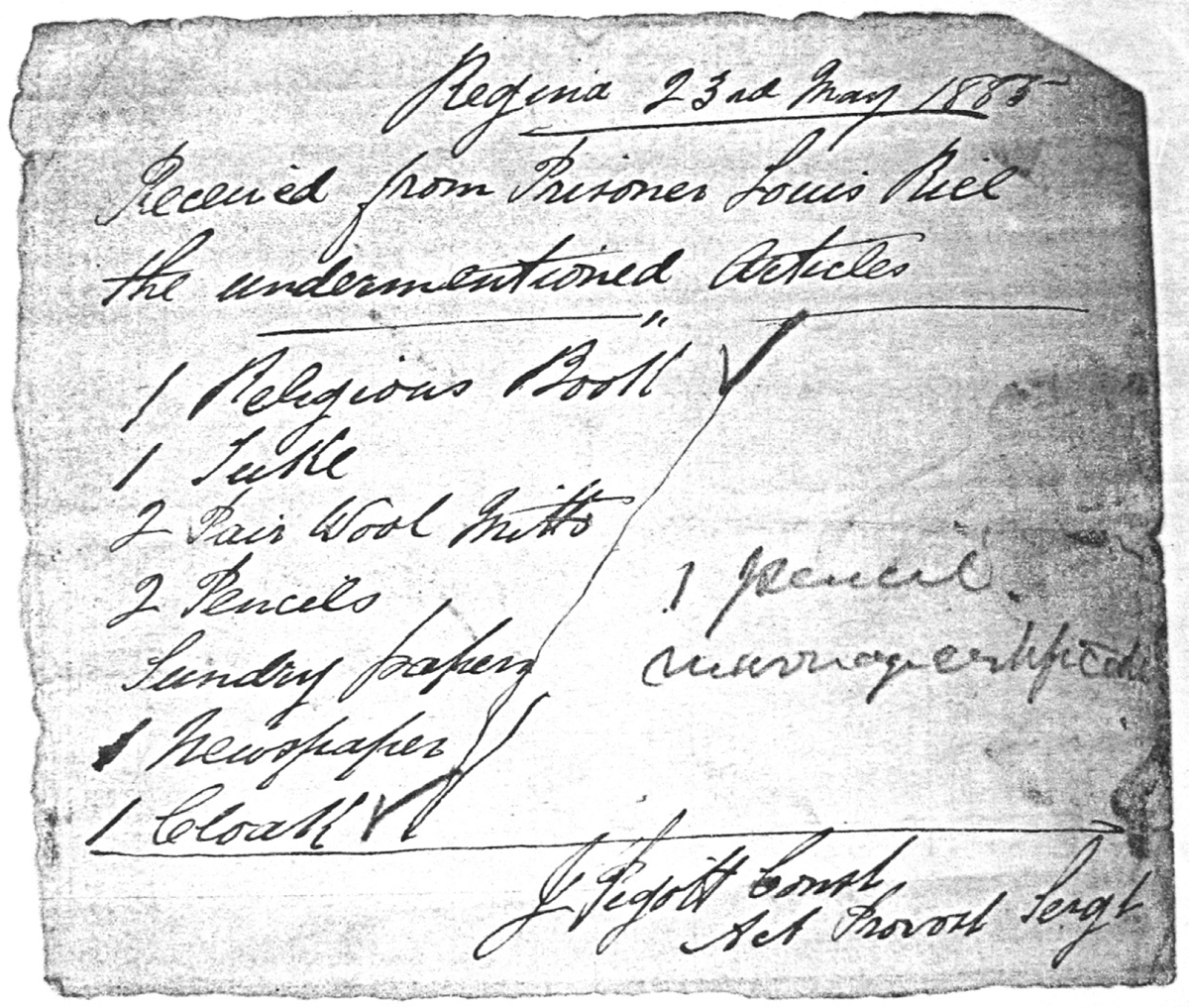

Riel and Dumont had hidden in the Minitinas Hills south of Batoche for three days. After assuring himself that his family was cared for, Riel spent most of the time praying. The soldiers were scouring the hills in search of the combatants. By May 15, 1885, Riel had decided. He walked up to a soldier, introduced himself and surrendered. Other than the clothing on his back, Riel had nothing but a bible, some papers and pencils, and his marriage certificate.

List of the items Louis Riel had on his person when he surrendered (Teillet family papers)