Riel was held under tight security. The soldiers were afraid the Métis would attempt a rescue. But Riel was not focused on rescue. His mind was on his wife, Marguerite, and his two children. Marguerite was sick with tuberculosis, she had no home, she was pregnant and she was now the sole support for their two children. Louis’s brother Joseph went to Saskatchewan to pick up Marguerite and the children. He took them back to St. Vital, where the Riel family cared for Marguerite and eased the fears of Louis’s two children—each now a war child with all the trauma and scars that war leaves on a child’s body, heart and mind. It eased Louis’s heart that his family would be cared for.

Louis also worried about the Métis left back in Batoche. When he heard that Gabriel Dumont had escaped, he was pleased. But he had no idea what was happening to the rest of the people. The truth is it was bad there. The Métis combatants who were captured were transferred to Regina. Twenty-four men were charged with treason felony.1 The other men fled, mostly to the United States. The women were left in houses that had been burned or shelled or looted by the army. Money, horses, cattle and food were stolen and fields were destroyed. The women back at Batoche lived in the ruins. Nine of the women of Batoche died shortly after from consumption, flu or miscarriages. Madeleine Dumont died shortly after joining Gabriel in the Montana Territory in 1886. Younger widows had to depend on other families for shelter and sustenance, or else they had to remarry. One woman found a job teaching at Vandal School near Fish Creek, but the only job available for most of the women was as a domestic servant. Josephte Tourond, Marguerite Caron and Marie Champagne rebuilt and managed their family farms.

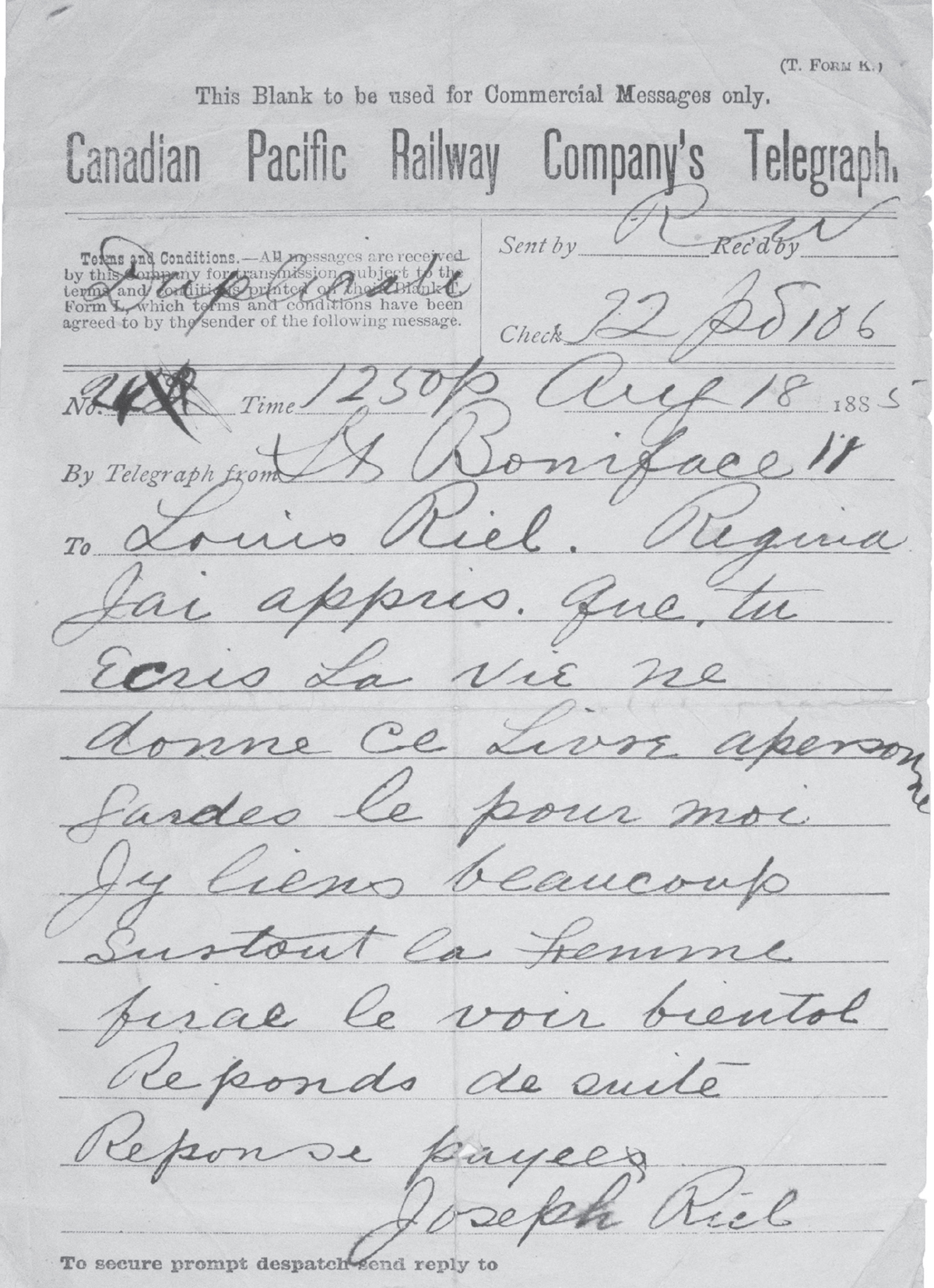

Louis Riel was transferred under heavy guard to Regina. On July 6, 1885, he was charged with high treason. Friends in Montreal put together a legal defence team, and the matter moved quickly to the courts. Knowing that lawyers were coming to represent him, Riel began to write. He saw the trial as his chance to speak, to justify what the Métis had done. He was being watched carefully and his writing became the subject of intense speculation. His brother Joseph was anxious to preserve his writings.2 But Riel’s immediate purpose in writing was not for his family or for posterity. It was meant to educate his lawyers. Knowing they were coming from Quebec and not fully versed in the issues, he wrote his justification for the North-West Resistance.

His lawyers thanked him for his efforts. At this point they were still humouring him. They arrived in Regina with a fully formed agenda, and nothing Riel said or did was going to change that. They had already decided on an insanity defence, and they were going to ram that through the court whether Riel liked it or not. He didn’t. He was adamant: if he was to die, it would not be as a madman.

Joseph Riel’s telegram to Louis asking him to save the book for him (Teillet family papers)

RIEL’S SANITY

Riel’s sanity is a touchy issue. The Riel family has never believed that Louis was insane. Joseph Riel firmly believed that Louis only pretended to be insane. Members of the Riel family to this day insist that Louis was not insane and that he only feigned insanity.3 Despite these claims there is evidence that Louis had periods in his life when he suffered from mental depressions, hallucinations and emotional disturbances. He suffered from depression after his father died in 1864. From 1875 to 1876 he was placed in an asylum under the name of Mr. David in Longue-Pointe, Quebec. Fearing the vengeance of the Orange Lodge, Dr. Howard later transferred Riel to the Beauport asylum.4 There is evidence that while Riel lived at Beauport, he was able to come and go freely and had several visitors. He met people in other villages and towns, such as Trois-Rivières. He even met with Wilfrid Laurier. Whether he was a voluntary inmate or not, Riel remained at Beauport until January 21, 1878.

The Riel family was not alone in its assertions that Louis was only feigning insanity. Three doctors who were his physicians over the years signed sworn affidavits attesting to the fact that notwithstanding “Riel’s peculiar views upon religious subjects which so strongly impress the ignorant and unreflecting with an idea of his madness,” he was perfectly sane.5

Was Riel insane or was he feigning insanity and seeking asylum from the Orange Lodge in the asylum? Riel’s own words likely provide the best insight into his mental state during the late 1870s:

I had come to believe myself a prophet. It seemed to me that the papacy should leave the moth-eaten soil of Europe for the new world. I saw the light of civilization grow from the Orient, the Euphrates, Palestine, Rome. It seemed to me that it was America’s turn, and I believed that I had an important role to play in the new order of things. By pen and sword I tried to make converts.

However, one day tired of fighting opposition, I asked myself if I was right or if everyone else was right. At that moment, the light came to me. Today I am better, I laugh myself at my hallucinations of my brain. I have a free spirit, but when one speaks to me of the Métis, those poor tragic people, the fanatic Orangemen, of the brave hunters who are treated like savages, who are of my blood, of my religion, who have chosen me as their leader, who love me, and whom I love as brothers, ah, alas! My blood boils, my head gets on fire, and it is wiser if I speak of other things.6

Riel’s sanity has never been an issue for the Métis. But it is an obsession with Canadian historians. The Métis Nation knows that, but generally finds the whole issue irrelevant to what the man did, what he stood for and their reverence for him. This is not to say that all Métis have always been without criticism of Riel. Some thought everything he did was wrong, and some thought everything he did was right, only he should have done more of it. Some wish he had given Dumont more freedom to direct the fighting in La Guerre Nationale. Some wish he had never been brought to the Saskatchewan at all.

But for most Métis, Riel continues to be their saint, aen saent, an intensely religious man who saw, talked and walked with God, the angels and the souls of the dead. They saw and continue to see his mysticism and visions as evidence that he was a man of God. They have generally thought the best of Riel, and the best of him includes, and has always included, his connection with God in his everyday world. Indeed, it is that very connection that recommends Riel to the Métis. Because of it, he was seen as being above corruption and above the commonplace world of opportunity.

The Métis also see the Canadian focus on Riel’s sanity as a double standard. They often point out that Sir John A. Macdonald was a drunk who disappeared for great periods of time into the bottle. During those times Macdonald was non-functional. It was a serious problem for the governance of the country, but no one tried to dismiss everything Macdonald did because of it. No one dismisses the political party he led or the people of Canada because Macdonald was a binge alcoholic.

At bottom, the Métis Nation wants Riel to be judged for his actions only. By that they mean one simple fact: Riel fought for them and he died for them. He was a mystic and deeply religious. He believed he had a mission from God. The Métis do not see any of this as evidence of insanity. They will not judge Riel by the mental illness standards of others. For the Métis, Riel’s actions amount to a grand gesture of defiance. Riel was their prophet, their inspiration and their leader. He died for the Métis Nation, for their rights, their lives, their lands and their very existence. Like him or not, think him insane or not, in the end all that matters is that Riel stood up for the Métis over and over again. That is what they remember him for. That is what they revere him for.

What Canadians remember Riel for is something quite different. French Canadians see Riel as the defender of their language. For others he is the voice of western alienation. He is a great Indigenous leader. All of these aspects can be critiqued in fact and in theory. All of them have been critiqued. They will likely continue to be part of Canada’s ongoing dialogue. But insanity—that is the obsession of Canadians and it is what got Riel hanged. At Riel’s trial the defence lawyers ran their insanity defence, and it was their insanity defence. It certainly wasn’t Riel’s chosen defence. The lawyers ignored Riel’s objections.

The injustice of the trial, including how it was conducted and its result, has always been a major source of discomfort for the Métis, and indeed for the entire country. So much so that there are conferences about the defence of Riel, and several books and journal articles, one of which was written by the former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Beverley McLachlin.7

The essential elements of what is still considered unfair break down into four issues: (1) the charges; (2) the venue, judge and jury; (3) the denial of time for defence to prepare; and (4) the lawyers.

Macdonald and the justice minister, Sir Alexander Campbell, decided to charge Riel with high treason under the 1351 Statute of Treasons. Why did the Crown proceed under a statute that was over five hundred years old when there were other options?8 The answer is simple: Macdonald wanted Riel to hang. He needed a statute that would guarantee a death sentence with no other option. If there was one thing Macdonald did not want, it was Riel alive and in prison. The only available statute with a mandatory death sentence was the 1351 Statute of Treasons. Both of the other statutes offered options of life imprisonment.9

Why did Macdonald want to hang Riel? There are several reasons. First, he needed to justify the massive public expenditure and the use of the army to put down what was really a small, localized incident that should have been dealt with by negotiation or political means. Second, Macdonald wanted a permanent solution to the problem of the Métis. They had been a thorn in his side for decades and he wanted them eliminated.

But there was great sympathy for the Métis generally, especially in Quebec, which left Macdonald without the option of a mass execution. The Liberal opposition was loudly blaming the government for causing the uprising in the first place. Macdonald needed to distract public attention away from the government’s role in instigating the war. He also needed to undermine the opposition claims that the Métis had legitimate complaints. For both Church and state, blaming everything on Riel was the perfect solution. Hang Riel and they would cut off the head, the voice and hopefully the heart of the Métis Nation. Macdonald thought it was the perfect and permanent solution to the Métis problem.

There remains a curious irony that Riel, a man who lived every moment of his life with fear and love of God, was charged with being “moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil” and not having “the fear of God in his heart.”10 He faced six counts of levying war against the queen—two charges for Duck Lake, two for Fish Creek (Tourond’s Coulee) and two for Batoche. The duplicate charges for each battle reflect the uncertainty about Riel’s citizenship. The first three charges presumed he was a Canadian citizen. The last three charges presumed he was an American. In fact, Riel had become an American citizen in 1883, making the duplicate charges inapplicable. The statute under which he was charged—and hence the fact he was facing a mandatory death penalty—became clear only partway through the proceeding.

The trial was initially going to be held in Manitoba. There, Riel would have been tried by a jury of twelve composed of six francophones and six anglophones. Other protections extended by law to defendants would have been available to Riel. But Macdonald changed the venue to Regina. In Regina Riel would have a lesser justice in the form of a jury not of his peers and a political appointee instead of an independent judge. His jury was composed of six white Protestant men and a judge who got his job by an appointment from Macdonald, and who could be fired if he didn’t deliver the judgment Macdonald wanted.

Judge Hugh Richardson didn’t speak French, which put Riel and all the francophones at a severe disadvantage. He denied all of Riel’s lawyers’ motions—seeking more time to prepare, to call witnesses and to obtain evidence. His conduct over the Métis trials showcased the patronage system that got him appointed. His decisions provide enduring evidence that he was not a highly skilled lawyer or judge.

Riel’s lawyers were respected members of the bar and they worked conscientiously, but not on his behalf. Instead it appears they were working at the behest of the Quebec men who retained their services, and they reported to the priests. If they had worked for Riel, they would have respected his wishes as to how to conduct the defence. They would never have run an insanity defence over his objections, and they would have called to the stand at least some of the thirty Métis witnesses who were jailed next door. Instead they called no one and they resolutely resisted Riel’s objections to the testimony put forward by the witnesses. This behaviour is highly problematic. It was 1885, but a lawyer was still obligated to represent the client’s wishes, even if it would result in a guilty verdict. Every person has the right to determine his or her own defence, and no lawyer has the right to override that wish. But that is what happened to Riel.

There was a fundamental disconnect between Riel and his legal team as to how the trial should be conducted. Riel wanted a justification defence. His defence team viewed that as a legal non-starter. Riel’s wish to run a justification defence was the only defence on the merits of the case. None of the other defences—insanity, questions about jurisdiction or breaches of his procedural rights—touched on what had actually happened to the Métis on the South Saskatchewan. Riel wanted nothing to do with any of the procedural defences. He wanted to defend himself based on the merits of the Métis cause. That, after all, was what the North-West Resistance had been all about.

Riel’s mistake was to believe that justice in the Canadian system was available to him. He never wavered in his wish to present the Métis case to the court. But no one would allow the Métis case to be heard in the court—not the judge, not his lawyers and certainly not Macdonald. Riel was allowed to make his statement, but it was not evidence that could be considered by the jury. Perhaps Riel was insane—to believe he could get justice for the Métis in a Canadian court.

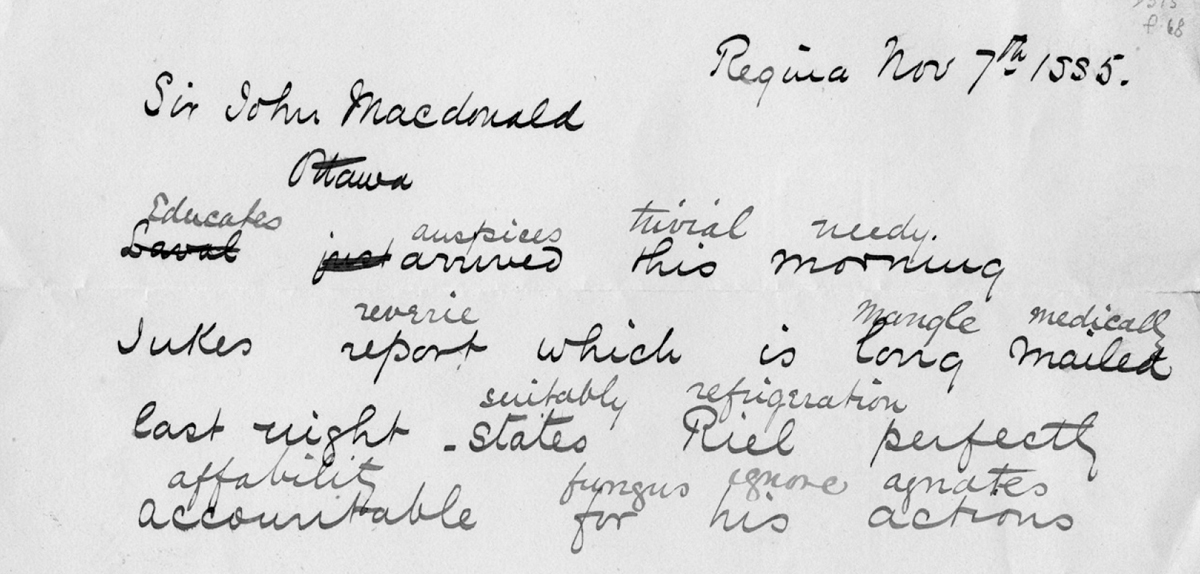

The jury found Riel guilty but recommended clemency. Richardson sentenced Riel to hang. The Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench dismissed the appeal. The Privy Council upheld the dismissal. The ball was then squarely in the court of Parliament. The prime minister, under pressure to at least appear neutral, appointed a medical commission to inquire into Riel’s sanity. Dewdney confirmed Riel’s sanity in a coded telegram to the prime minister. No one was surprised when Parliament confirmed Riel’s sanity and rejected the jury’s plea of clemency.

Riel’s code name is “refrigeration” in Dewdney’s coded telegram to Macdonald confirming Riel’s sanity (Glenbow Archives M-320-1482)

THE PETITIONS

Thousands petitioned the government about Riel.11 The Orange Lodge immediately registered its demand that the sentence be carried out and clemency of any kind be refused: “[I]t is the sweetest savor of their nostrils to annihilate us [the English-speaking people in Canada] . . . but with the blessing of God we will yet conquer the blood-thirsty Indian and all his abettors . . . if this Riel, who is all of French and Indian instinct, will receive the gallows, then the English-speaking people might be more secure of their lives.”12 But most of the petitions sought clemency for Riel. There were fifty-seven petitions and telegrams from those who wished Riel’s sentence to be commuted. They came from France, Great Britain, the United States, Quebec, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. They were signed by one person, or by hundreds, or by almost two thousand.13

The petitions raised various reasons for clemency. Some claimed that Riel’s actions were the result of his aberration of mind, which raised a doubt as to his legal responsibility. One petition frankly called Riel a crank lacking the intellect necessary to be held responsible for his acts. Many of the petitions pointed to the lack of a fair trial.

Over eight hundred people from Chicago signed a petition saying that Riel’s cause was that of all the Métis of the North-West, and his execution would be a refusal to do justice to a great portion of the population of Canada, with consequences. Some petitioners said the cause of the insurrection was the refusal of the Canadian government to grant to the French population of the Saskatchewan District their just rights and privileges that had been promised to them in 1874 by Lieutenant-Governor Morris. Petitioners from Quebec claimed:

[T]he offence of which the said Louis Riel has been found guilty is purely political, and is shared in by a great number of Her Majesty’s subjects and . . . the cause of Riel is that of all the . . . [Métis] of the North-West, of whom he was constituted the defender; that the rights of these people cannot be ignored without refusing them that justice which is due to every free citizen . . . and the execution of Riel . . . might become a cause, much to be regretted of dangerous conflicts and might drive to despair respectable and peace-loving people.14

Some of the petitions wanted the sentence to be delayed until a special commission had inquired into the nature of the troubles in the North-West and made a report. Two thousand people from Quebec drew attention to the many petitions sent by the Métis before they resorted to arms. Others argued the Métis had only taken up arms to defend their rights. The American under secretary of state urged clemency, noting that the causes that “provoked the revolt of the North-West, the extraordinary proceedings which characterized the trial . . . [and] the ill-feeling generated by these facts” were some of the many powerful reasons to commute the sentence.15

Americans pointed out that if their revolution had gone the other way, Washington, Franklin, Hamilton and Adams would have ended their days upon the scaffold. They quoted Burke’s argument that “you cannot frame an indictment against a people.”16 Nor can you, they said, inflict capital punishment on one man for participation in public or quasi-political movements in which large bodies of people took part or sympathized.

The Métis from all over the North-West petitioned for Riel’s life. The Métis of Red River sent fifteen petitions signed by Riel’s relatives, supporters and friends, including his comrades in the Red River Resistance, André Nault, Elzéar Lagimodière and August Harrison.

And finally, from the only petition not signed by men: “A woman begs Canadian authorities pardon Riel.”17

HIS SOUL GOES MARCHING ON

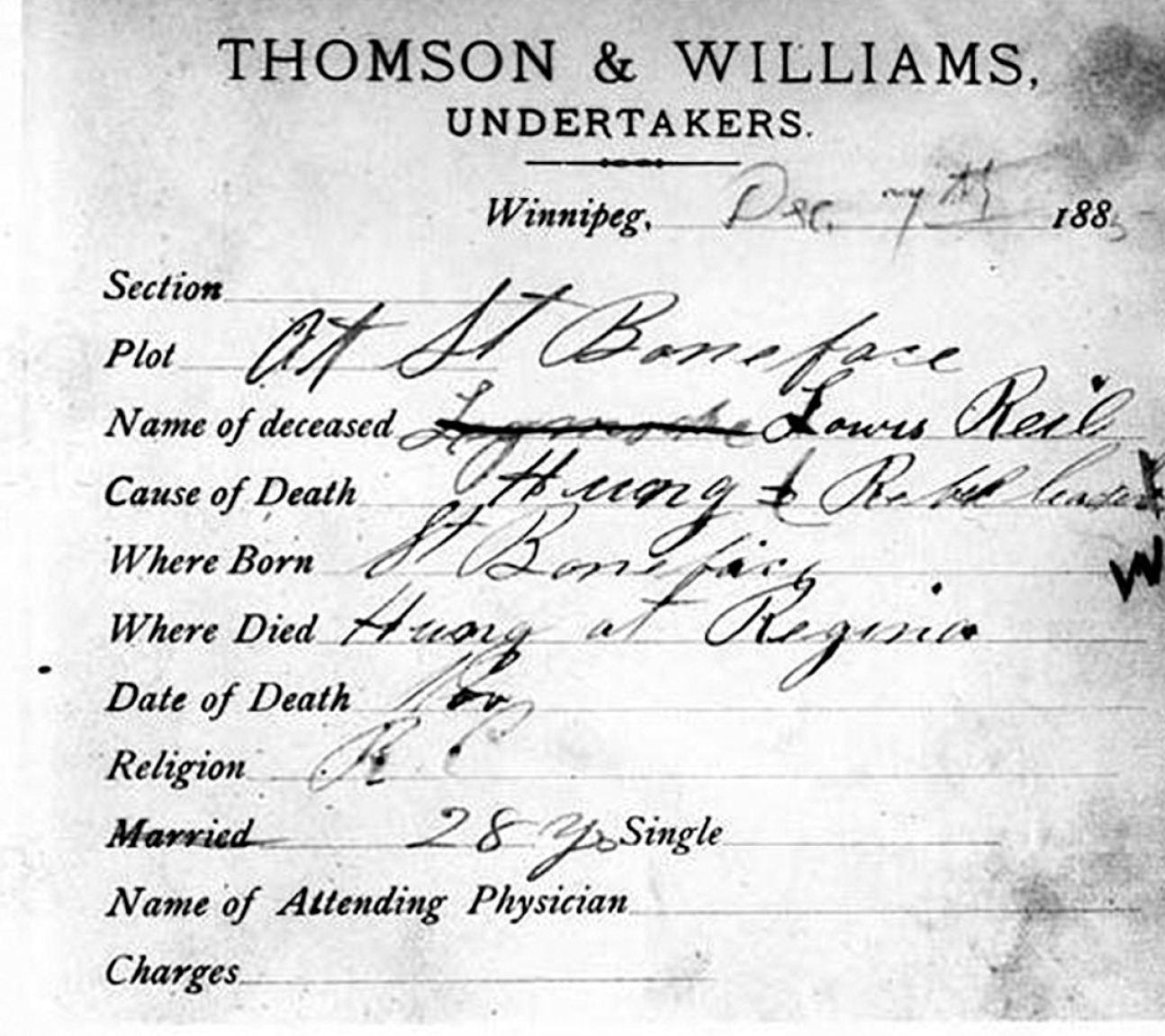

On the morning of November 16, 1885, the rising sun revealed a stunningly beautiful hoar frost coating the grasses, the trees and a brand-new gallows in Regina. It was the morning Louis Riel was to be hanged. By all accounts, Riel met death with great dignity. He made no final speech to justify his actions. He simply prayed and gave his soul, heart and body into the keeping of the God he had loved and served.

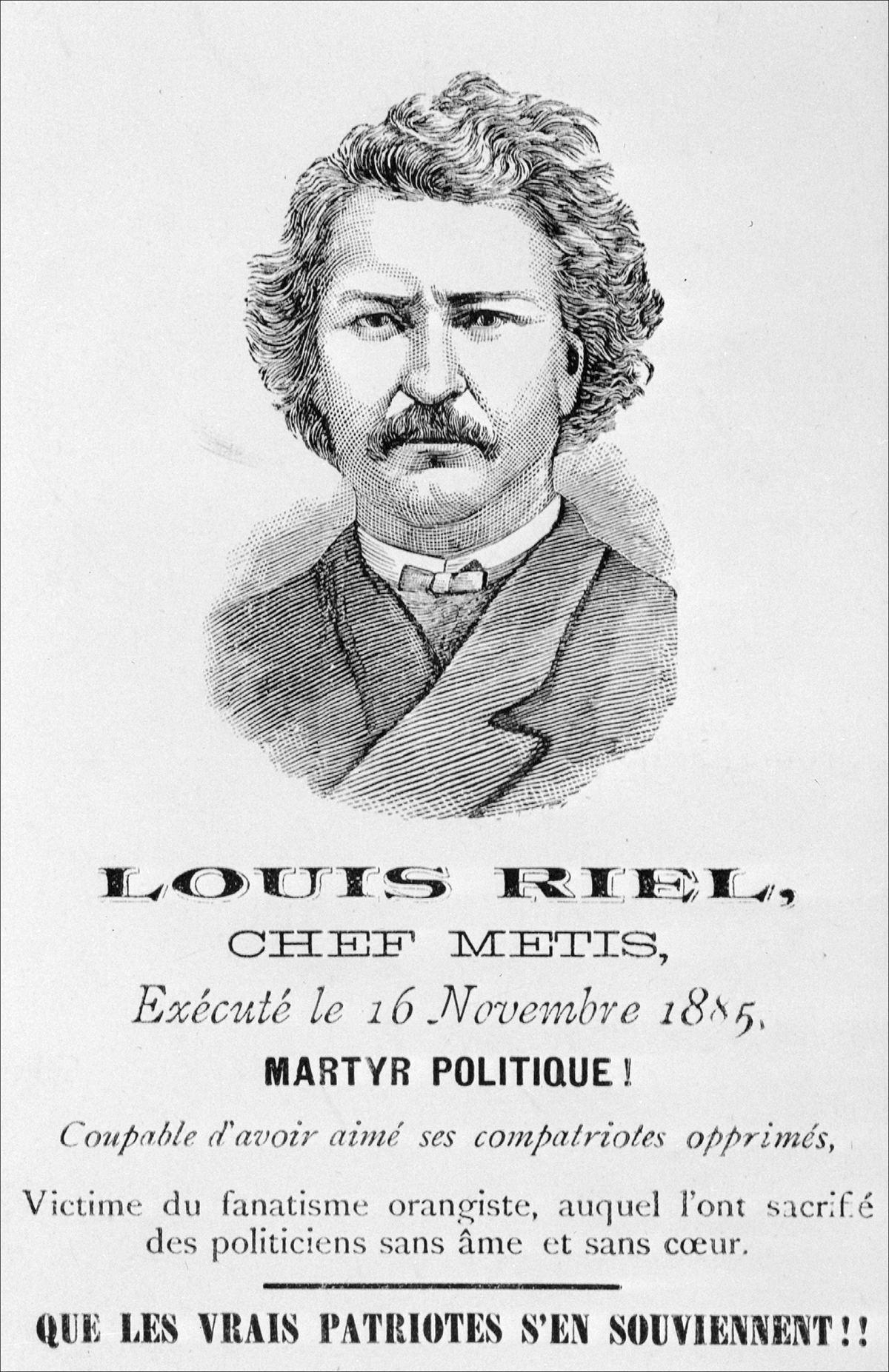

This quiet but profound gallows scene was not mirrored in the world outside. There the world was shrill with vitriol. Fifty thousand marched in the streets of Montreal, crying for Prime Minister Macdonald’s head, while the newspaper headlines in English Canada crowed with victory at the death of the hated Riel. The excuse for hanging Riel was the North-West Resistance. But English Canada really hanged Riel as revenge for Thomas Scott.

Comparisons between Riel and John Brown arose immediately. John Brown and a small band of men had raided Harper’s Ferry to rouse Americans against slavery. The opinion of the day was that John Brown was a crank. When Riel was hanged, Americans were quick to see the parallels between two men who were in the vanguard of what they called a “revolt against tyranny.” Americans, no fans of the British, opined that it would be “difficult to find a place, no matter how inhospitable, where the blasting breath of British tyranny does not make itself felt.”18

Louis Riel’s death certificate (Teillet family papers)

The Métis Nation did not die with Riel on that day in 1885. The Nation had suffered a blow, but within two years the Métis were already gathering their forces and forming a new organization. Riel was dead, but his soul became the spark that kept the flame of the Métis Nation alive. Like John Brown’s movement, Riel’s ideas would permeate the North-West and become a magnet around which Métis Nation rights and title would galvanize and begin to take more substantial form in the laws of Canada. Riel gave up his life for the Métis Nation and its rights. He has never been forgotten, and eventually, Canadians began to recognize the justice of the cause he fought for.

To this day Macdonald is remembered for slandering Riel and Quebec all in one ugly sentence when he said, “He shall hang though every dog in Québec bark in his favour.”19 But in hanging Riel, Macdonald ensured that Riel would live. On that fateful day in November 1885 when Riel was hanged, Macdonald created exactly what he sought to extinguish: a martyr and a movement. Both march on.

“Riel—Martyr Politique!” This handbill was printed, circa 1885, by l’Union, St. Hyacinthe, Quebec. (Library and Archives Canada C-018084)