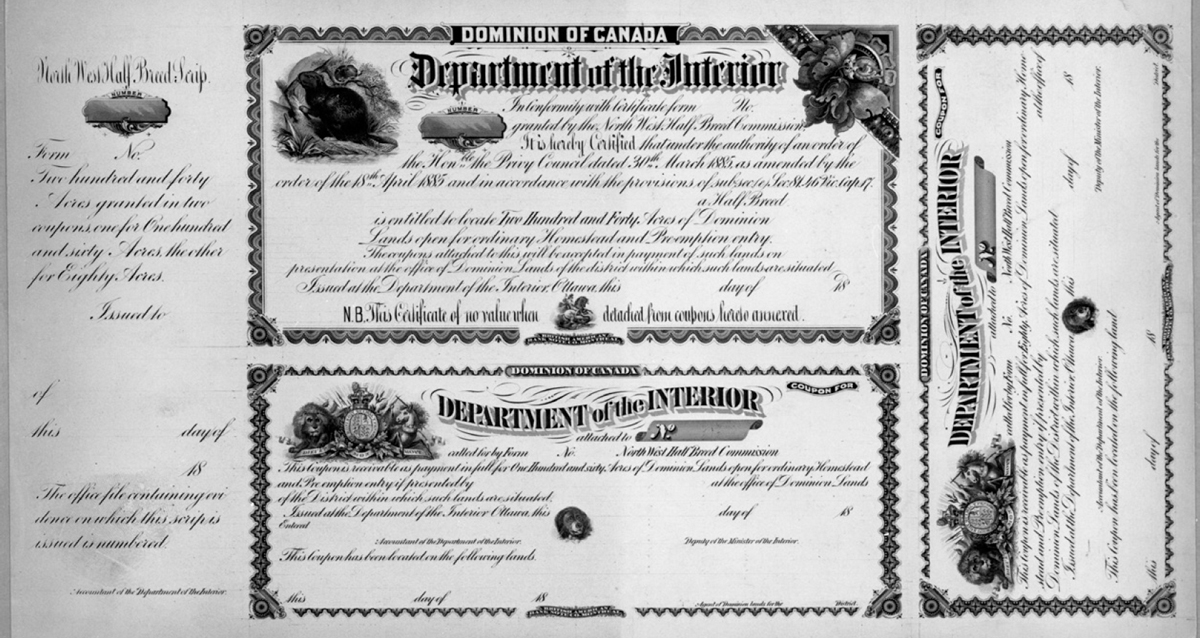

Scrip is obsolete now and virtually unknown to most Canadians today. But it’s still a household word in the Métis Nation. Scrip was a coupon that could be redeemed for money or land. Money scrip was usually issued in the amount of $80, $160 or $240. Land scrip was a coupon that, once cashed in, was supposed to issue to the bearer a plot of land in the amount of 80, 160 or 240 acres. Though a scrip coupon felt and looked like a large banknote, it did more than provide money or land. Scrip was a reward, a pacifier and an eraser. Both sides of the North-West Resistance received scrip. Soldiers were rewarded for their services with scrip. The government used scrip to pacify the Métis and to erase their claims to Aboriginal title. The Métis scrip process was a rotten deal. And everybody knew it.

SCRIP AND TREATY

If scrip was just a grant of land for the Métis, as it was for the soldiers, it would not have been such a rotten deal. But it was much more than that. It also purported to extinguish their individual identity as Métis and their collective Indigenous title to land. Since the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Britain, and then Canada, had operated on a policy that Indigenous lands could be purchased and title to their lands could be extinguished. For First Nations, treaties were the means by which this extinguishment was accomplished. One should not assume that the First Nations believed or have ever accepted that their treaties extinguished their title and rights. But the government always had control of the pen in drafting the treaties and control of what was explained to the First Nations during the treaty “negotiations.” So the English versions of the treaties invariably contain cede, release, surrender provisions that purport to extinguish Indigenous title to those lands and transfer them to the Crown. Treaties were the wholesale transfer of large swaths of land to the Crown from one or more First Nation bands. Scrip was meant to accomplish the same thing, only it was done on an individual basis because the Crown did not accept the existence of a Métis collective with title and rights.

Métis scrip issued by the Department of the Interior (Glenbow Archives NA-2839-3)

There were several options on the table for Métis. If they were closely connected with a First Nation band, they were usually allowed, with the permission of the chief, to join the band and take treaty. Indeed, several chiefs pleaded with the Crown negotiators for Métis to be able to join them. When the Métis began to negotiate with the treaty commissioners, they requested their own bands and their own reserves. This is what happened in the Half-breed Adhesion to Treaty #3.

Many Métis took advantage of these opportunities, joined treaty and in so doing became “Indians.” This happened often where treaty preceded scrip. When scrip was offered later, some Métis opted to transfer from treaty to scrip. There are also examples of Métis who took scrip and then switched to treaty. Some switched more than once. It was by no means a process with a clean divide between Métis and First Nations.

SCRIP PROCESS

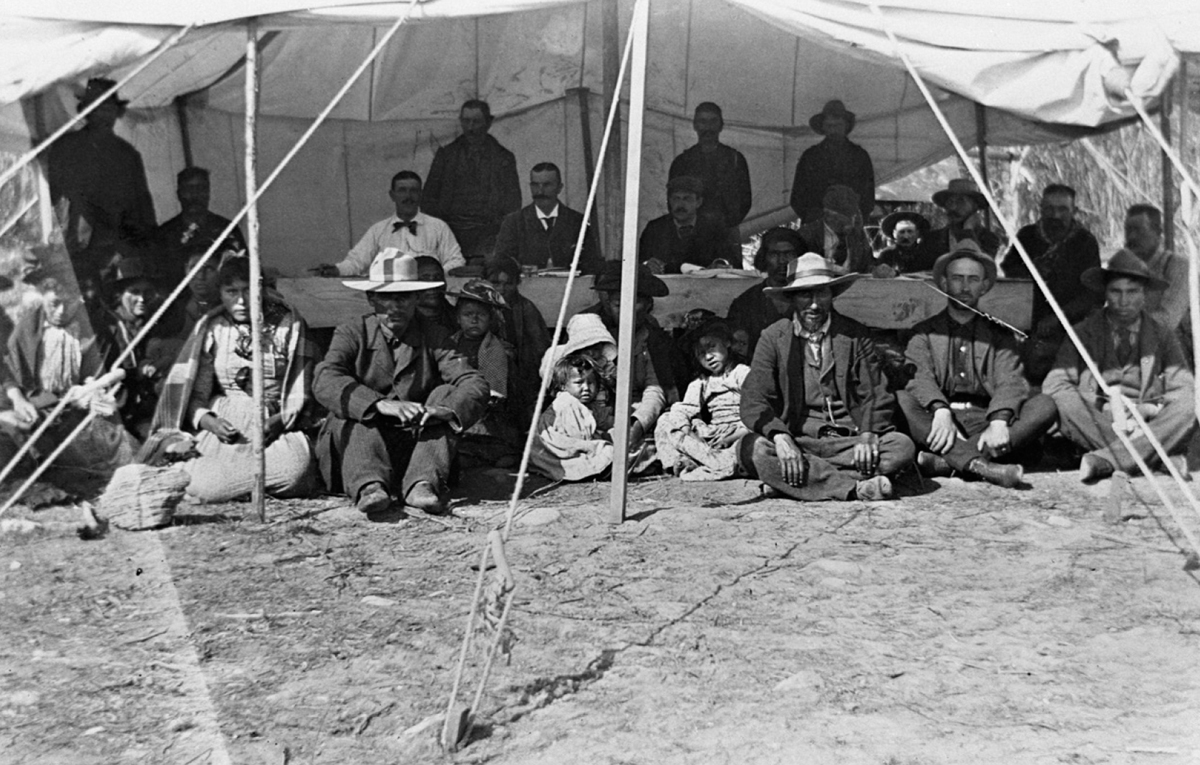

The scrip application process was intimidating. Louis Morin described the scrip commission’s visit to Île-à-la-Crosse. According to Morin, the scrip commissioners set up their office in a large tent and two Mounties stood on each side of the tent opening. The Métis had to enter the tent by walking through a police gate. The Mounties made an impression on the Métis, just as they were meant to. Police were used to put pressure on First Nations to sign treaties, and it was no accident that they were prominently placed at the entrance to the scrip commission tent. The Mounties were the gatekeepers of the process, a none-too-subtle display of Canadian force.

The application process was also an administrative nightmare in which fraudsters and impersonators, speculators, priests, lawyers and agents for the banks all took advantage of identity, language, geographic and literacy difficulties to obtain scrip. The speculators travelled with the scrip commission and were virtually part of the official party.

Interior of a scrip commission tent at Lesser Slave Lake, Alberta (Glenbow Archives NA-949-22)

In an attempt to maintain at least the appearance that the scrip commission was independent, most of the speculators were not allowed into the commission tent. The priest, however, had a place inside the tent and was in a privileged position to obtain scrip certificates of entitlement. “Obtain” is the appropriate word because, unlike the other speculators who at least paid something for the scrip certificate, the priests used their influence to have it passed over to them gratis. Once the commissioner issued a certificate, the Métis applicants had to walk by the table where the priest sat. The priest would hold out his hand and ask if they wanted him to care for their certificates. Many did. Asked if the priests ever returned the certificates, Louis Morin shrugged and said he never knew the priests to give anything back.

If the Métis family declined to hand over their certificates to the care of the priest, they had to exit the tent through the Mountie gatekeepers and face the other speculators who offered a trade: paper cash for the certificate. Unable to read or write and having little or no experience with paper money, the Métis, particularly in the north, were at a severe disadvantage. The cash offered was much less than the value of the certificate, but many exchanged one piece of paper for the other.

SIGNED WITH AN X

Because most Métis at the time were illiterate, they signed their applications with an X, and the commissioner or his clerk wrote the applicant’s name above and below the X. We have already noted that Joseph Riel was literate but his application was inexplicably signed with an X. For the illiterate, impersonators conveniently completed the process. One of the speculators fessed up about how it worked:

[T]he buyers, when purchasing the scrip, would have the vendor sign a form of Quit Claim Deed. He would sign by making his mark, and this would be witnessed by two persons, presumably other dealers . . . the practice was for the holder of a scrip to pick out some local Indian or half-breed and take him to the Dominion Land Office and present him as the person named in the scrip. The holder of the scrip, pretending to be the agent of the half-breed, would designate the land.1

One of the impersonators was a man named L’Esperance. Monsieur L’Esperance attested to fifty conveyance instruments and forty-eight land scrip coupons or identified coupon holders in eight cities.2 Since it is simply not possible for one man to have done all this, the creation of Monsieur L’Esperance provides a good idea of just how widespread the fraud was. An official with the federal Department of Justice described the process:

It appears that the scrip was handed to the half-breeds by the agent of the Indian Department and it was then purchased, for small sums of course, by speculators. However the half-breed himself was required by the Department of the Interior to appear in person at the office of the land agent and select his land and hand over his scrip. In order to get over this difficulty the speculator would employ the half-breed to impersonate the breed entitled to the scrip. This practice appears to have been very widely indulged in at one time. The practice was winked at evidently at the time and the offences were very numerous.3

It was a system that could not have been implemented unless it was aided and abetted by land agents, lawyers, the Dominion Lands Office and perhaps the scrip commissioners themselves. Everybody knew about it.

The government certainly knew there were impersonations and forgeries and that these were criminal offences that should have been prosecuted under the law.4 But in the opinion of Parliament, it was best just to change the law to make sure nothing interfered with the process of removing Métis title to the land and laundering their title into the market. The Criminal Code was amended to put a three-year limitation on all offences relating to “the location of land which was paid for in whole or in part by scrip or was granted upon certificates issued to half-breeds in connection with extinguishment of Indian title.”5

In some cases a diligent Métis applicant would have had to travel over a thousand miles to locate scrip lands, and the trip would cost more than the land was worth. The entire process could take four years to complete, and the Métis applicants often had nothing to do with any of it after signing the application. The government proclaimed that no assignment of the right to scrip would be recognized in third parties. But it was third parties, not the Métis, who ended up in possession of the land scrip coupons. When it was all over, the Métis had virtually no land. The speculators, the banks and the Church ended up with the land and profited from the transactions along the way.

One problem was that a scrip coupon could not be converted to any land. Scrip had to be located on lands already open for homesteading on surveyed lands. There were no surveyed lands open for homesteading in the north. So Métis in the north who wanted to actually obtain land with their scrip had to move south. If you were already settled on lands in the south, you could not use your scrip to secure your homestead. This is why everybody knew the Métis would not end up with the land. Métis scrip was good for only one thing—selling.

SCRIP DOCUMENTS

For forty long years from 1885 to 1921, North-West scrip commissions travelled around Métis communities taking applications.6 Scrip was a failure when it came to keeping land in the hands of the Métis, which was its stated purpose, but everybody knew that when it started. On the plus side, and only with the hindsight revealed by much academic work, the scrip documents have turned out to be a gold mine of information about the Métis Nation. The scrip application asked applicants for family information, including who their parents were and whether they were Métis, where they lived now and in the past, if they were married, how many children they had, where their children were born and where they died.

The answers in the scrip documents show important events in the Métis collective memory. They all knew where they were during the “rebellions.”

I was in Montana in 1871. The year of the first rebellion I was between Cypress and Moose Mountain . . . The second rebellion I was in Montana Choteau County.7

I saw Melanie [Deschamps] first at Judith’s Basin . . . It was the year after the rebellion that she died.8

I knew Pierre St Germain . . . and his brother Louis . . . before the Red River Rebellion.9

I have known Louison Nipissing as long as I can remember . . . [His daughter] Madeleine is sixteen years of age . . . She was a year old when the rebellion was in progress.10

Despite the Old Wolves’ objection to the use of the term “rebellion,” the scrip records use it often. The documents always read as stiff English translations, so it is unclear whether “rebellion” is the actual word the Métis used, or whether it was the word the scrip commissioners wrote down.

In the responses to questions such as “Where have you lived?” and “Where do you reside?” each answer was usually a long list of locations. The Métis remembered where they were when their children were born, and since they tended to have a child every two years, the birth locations provide an extraordinary cache of evidence about their migratory patterns.

The documents show that thousands of Métis had no permanent place of residence.

Most of my life has been spent with Louison Nipissing, hunting together in the days of the Buffalo and making a living since.11

I was born in the North West . . . I was married to Gabrielle Leveille about thirty five years ago. We lived the life of hunters in the North Western Plains. Went every spring to Winnipeg to dispose of the result of the chase. We had our winter quarters in the territories, and we went to Winnipeg to trade our furs.12

I knew Pierre St Germain . . . He followed the chase. He built a house at Cypress Hills to winter in. After living there a year he built another house at Wood Mountain. It is twenty five years or more since he became a resident of the territories . . . George St Germain [Pierre’s son] was born on the trail as his parents were taking to Winnipeg the proceeds of their winter’s hunt. That is nineteen years ago.13

Some applicants made simple statements such as “My parents were Plains hunters.”14 But when the application reads, “having no permanent domicile in either previous to the transfer,” it seems to be the language of the commissioner.15 It is difficult to imagine a Métis hunter using the word “domicile.” The scrip applications and witness declarations contain valuable information, but they cannot be taken as the words of the Métis. They are the translations and interpretations written down by the commissioners.

While “domicile” was a commissioner’s word, other words have a more authentic ring. Thousands of scrip records refer to the “Plains.” It is a curious example of how the language has changed. Today most Canadians think of the Plains as American and call our flatland “the prairie.” But back then Métis hunters always spoke of the Plains. Nancy Bird was born “on the Plains” and Marie Desjarlais was married “on the Plains.”16 Sometimes the location is more specific. Baptiste Cardinal’s child “died of small pox on the road between Carlton and Lac La Biche.”17 On a happier note, Elizabeth Boucher’s “mother married . . . in the Plains near Battle River.”18

Nowhere on the scrip application does it say that scrip was a legal exchange for the extinguishment of Métis Aboriginal title. After all the chatty personal questions, there was only one question that gave any indication of the legal implications buried in the scrip application: whether the applicant had ever accepted commutation of their Indian title.

There is simply no Michif or Cree translation for “commutation.” Most people today don’t know what “commutation” means, so one can readily imagine the translation difficulties back in the late 1800s or early 1900s. For those who are not lawyers, “commutation” means substitution. In criminal law commutation is usually the substitution of a lesser punishment for the original sentence. In the context of scrip, the term appears to have been borrowed from the Indian Act, where it was used to extinguish the rights of First Nation women who married non-Indian men. So when the scrip commissioner asked a Métis applicant if he or she had ever accepted commutation, he was asking whether the Métis applicant had ever taken a payout for leaving treaty, or if the Métis applicant had taken a land grant under the Manitoba Act or scrip elsewhere.

It is doubtful that any of the Métis appreciated the legalities of scrip, especially that it would forever extinguish their Métis Indigenous title. Most Métis believed the scrip process was not a one-time deal and would be repeated in the years to come. Indeed, it was common talk among the Métis throughout the Prairies that scrip would be reissued. This was a reasonable interpretation because the Métis knew First Nations received annual treaty payments. It suggests that the Métis thought the scrip process was more akin to lease than sale of their rights.

Another fact that everybody knew was that in the north, even as late as 1906, money was not commonly used. They were still using the “made beaver” system with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Made beaver involved stacking pelts against a gun and the Company assessing how much purchase power they stacked up to. The stack would be valued differently according to the type of pelt and its condition. This was how the Métis in the north valued and purchased goods. While the Métis in the south had experience with money, the Métis in the north had no experience of how to value land and little knowledge of cash.

Scrip was issued only on an individual basis. Canada would not deal with the Métis Nation as an Indigenous collective. It would only—and even then grudgingly—agree to recognize Métis rights in individual parcels for the sole purpose of extinguishing those rights. It was a system of massive land speculation laundered through Métis scrip. By the end of the scrip process, which took decades, the government claimed Indigenous land rights for all Métis in the North-West had been extinguished and washed its hands of any further obligations to them. Virtually no Métis ended up with land but all Métis title was considered legally extinguished. The Supreme Court of Canada called it “a sorry chapter in our nation’s history.”19

SCRIP GEOGRAPHY

In order to access scrip, the Métis applicants had to be in the right place at the right time. But it was almost impossible to know what the right places and times were. They kept changing. Shifting borders always seemed to be called in to the effort to deny claims. The border between Manitoba and Ontario was one of the shifting borders.

Exactly where the border between Manitoba and Ontario was became the subject of a long legal dispute. Canada delayed approving Manitoba Act land grant and scrip applications for those who lived near that border pending a final determination on where it lay. In 1889, when the border was finally determined, the Métis who lived on the Ontario side of the new border on July 15, 1870, were denied. Métis who claimed they were in Manitoba on July 15, 1870, were theoretically eligible.

But not Old Nick Chatelain. He filed his claim in Winnipeg in 1878. Despite living most of his life in the Lake of the Woods/Rainy Lake area of Ontario, he claimed that he was in Red River on July 15, 1870, living with his daughter Marie Anne and her husband, Jean Baptist Ritchot. The evidence suggests that Chatelain was indeed in Red River on that date. Chatelain was deeply connected to the Métis participants in the Red River Resistance. His grandson Janvier Ritchot was the man who first stepped on the surveyor’s chain and sat as a judge on the panel at the Thomas Scott trial. It was Chatelain who met with Riel and proposed dumping logs on Wolseley’s army. That would have been in the summer of 1870.

Maybe the scrip bureaucrats knew about his diabolical suggestion. After all, it had been published in La Minerve. Perhaps they doubted his claim of residency in 1870. Perhaps they wanted to punish him for his participation in the Resistance. Regardless, they denied his claim and most of the other Métis claims from that region. Very few were approved. It was a convenient way to deny Métis in northwestern Ontario any resolution of their rights.20

The other border that mattered was the American border. The United States had a history of including Métis in their treaty negotiations with First Nations. In many treaties American Indians insisted on including their Métis relatives.21 In 1882 twenty-two townships along the Canadian border in Dakota Territory were set aside for treaty with the Chippewa. This was Turtle Mountain territory, and many Métis came home from Montana to take treaty. Over three-quarters of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa band were Métis.

The parties were split on what they wanted from the treaty. Chief Little Shell wanted to include the Métis who were related to the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, whether they were Canadian or American. The chief wanted the land to be held in common and he wanted the size increased to include the many Métis. The Métis wanted the land in severalty, meaning they wanted to own their parcels individually and not in common. Other Chippewa wanted to exclude the Canadian Métis. These discrepancies were never truly resolved, and Little Shell later repudiated the treaty originally signed in 1892. It took another twelve years to finalize a treaty.

Dividing the Métis into neat parcels of Canadian and American citizens missed the complexity of facts on the ground. Many Métis simply didn’t know whether they were American or Canadian. During their hunts the Métis wandered back and forth across the invisible border. It was no easy matter for a nomadic group to say exactly where each child was born. Indeed, it seems that some Métis didn’t understand the concept of state citizenship. Annie Jerome Branconnier remembered coming across the border from Walhalla (formerly St. Joseph), North Dakota, in the early 1900s. When her family were asked their nationality, they said they were Métis. They didn’t see themselves as Canadians or Americans.

Choices about state citizenship were often made based on where the best offers were. Some Canadian Métis who were excluded from the 1892 Chippewa treaty began to return to Canada. When the Canadian government, in 1901, offered a new round of scrip to the Métis who had not received it between 1885 and 1886, more Métis crossed the border, thereby affirming their citizenship as Canadian. Another wave came to Canada after 1904.

But a significant number of Métis remained in North Dakota to take advantage of the land allotments offered by the treaty. Today, the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Band has a population of over thirty thousand. Despite its name, the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Band could be seen as an American Métis community. It continues to develop its Métis culture, and as with all Métis communities, it is heavily influenced by its familial ties and proximity with the Chippewa. The band has always maintained many ties to Canadian Métis, especially those who live on the Canadian side of the border at Turtle Mountain. It was at Turtle Mountain that the first Michif dictionary was published. It was at Turtle Mountain on the Canadian side in 2009 that Will Goodon shot the duck that eventually led to the resolution of Métis hunting and fishing rights in Manitoba.

Aside from the useful information we can now glean from the scrip documents, one must ask why the Métis wanted scrip. The Métis in Saskatchewan knew their cousins in Red River had been paid for their rights, but they also knew their relatives in Manitoba didn’t end up with land. According to Patrice Fleury, the Métis on the Saskatchewan first heard about scrip in 1883, when some of their relatives from Red River arrived and told them about the money they had received. The Métis in Batoche believed they had the same rights as their cousins in Red River. They didn’t think it was fair that scrip went only to some children of the same family, merely because they resided in Red River on a particular date, while others who fled the reign of terror and now resided outside Manitoba got nothing.

The main cause of the North-West Resistance was the failure of the government to secure Métis landholdings. The mounting pressure on the government to resolve outstanding Métis land claims in the years and months leading up to the North-West Resistance pushed the government to set up a scrip commission to set aside land for the Métis heads of families and children. The government resisted until 1885, when it finally authorized an enumeration to implement the process that came to be known as North-West scrip. At first it was limited to those who would have received a land grant had they resided in Manitoba at the time of the transfer, so it was hardly a major concession. The offer didn’t protect existing landholdings and it would only apply to a few. The commissioners were appointed just before the outbreak at Duck Lake. It was too little, too late. The Métis had seen this dance before in Manitoba. All the while the lands slipped away.

In 1885 Commissioner W. P. R. Street started negotiations with the Métis in Qu’Appelle. They wanted their rangs protected and they wanted land scrip for their children. They would agree to buy the rangs at a dollar an acre if they got a free grant of 160 acres from the nearest vacant lot. The deal was confirmed within a week. The Qu’Appelle arrangement shows the possibilities of quick settlement. But why did the Métis have to pay for land they were already on? It only makes sense if the Métis grant lands were converted into homesteader lands and thus fit within Canada’s homestead policy.

The Métis community of Green Lake, Saskatchewan, provides a good example of how Canada’s homestead policy worked to the disadvantage of Métis applicants. It started always with the surveys, which were every bit as problematic as they had been in Red River and on the South Saskatchewan. Two different surveys were required before the process could begin. It took years, and the cost of the land tripled and the patent fees rose by a third while the Métis waited for confirmation of their properties. Some were allowed to purchase their land over time, but would pay more in interest than the value of the lot.

This is a brief taste of the “sorry chapter” of scrip. Canadians pride themselves on a history of fairness and good governance available to all citizens. Nowhere is this taken more seriously than in property interests. But the Métis got no justice and no fairness in their land dealings. They were denied Crown protection granted to First Nations for their treaty lands and were defrauded of the legal protections provided to other Canadians. The sorry scrip chapter remains an outstanding issue for the Métis Nation.