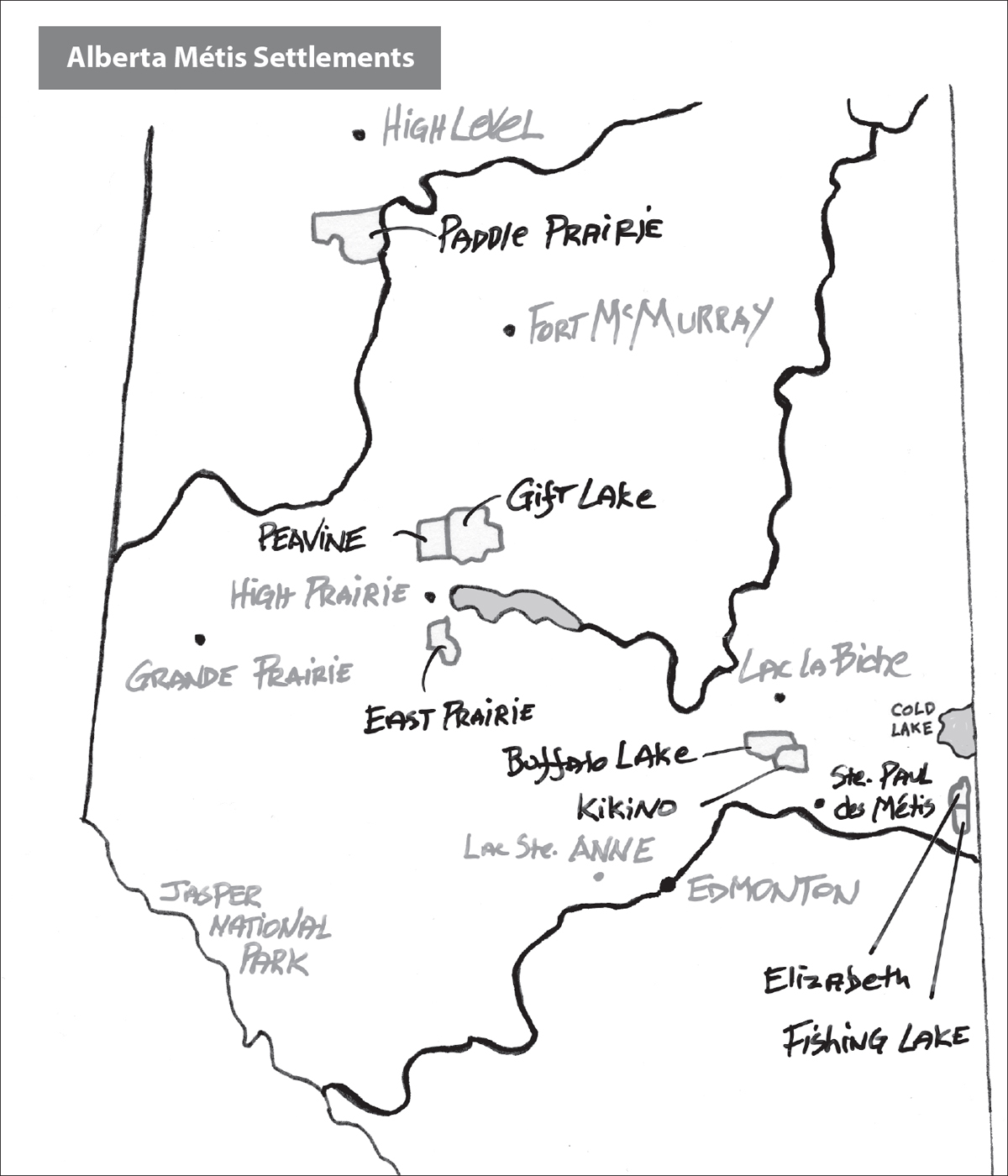

The Métis Settlements in Alberta

JIM BRADY AND MALCOLM NORRIS

The Métis Nation owes its continuing existence to a series of ardent nationalist leaders. Cuthbert Grant, James Sinclair, Jean-Louis Riel, Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont were not the only nationalist Métis leaders; they are only the best known from the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century new leaders emerged for the Métis Nation. In Alberta in the 1930s, they were Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris.

The early part of the twentieth century brought a world of change to the Métis Nation. In Manitoba the Old Wolves were at work telling the stories, erecting monuments, publishing their letters and writing the history of the Métis Nation. But theirs was a focus in the rear-view mirror, an effort to remember, to not lose sight of their ancestors and their history. The Old Wolves were keeping the stories alive for all the Métis Nation. In northern Alberta Métis communities, something else was brewing, a new evolution of the Métis national struggle. These communities had welcomed waves of Métis from Red River after 1870 and another wave of Métis from Saskatchewan after 1885. The Métis took their nationalist politics with them wherever they went. Under new leaders, the Métis Nation was evolving.

The language changed. People no longer spoke of the Canadian Party and their agenda. Métis leaders had new words to describe what was happening to them. They began to speak of their long resistance as anti-colonialism. Brady and Norris brought something new to the battle: labour and socialist theory. Like Cuthbert Grant and Louis Riel, Brady and Norris were well educated. They were both committed to continuing the national struggle of the Métis Nation.

Norris grew up in Edmonton with stories of the Métis Nation, especially tales of Riel and Dumont. In his mother’s stories, Riel was proudly remembered as a man who defended the weak. Brady grew up in St. Paul des Métis with the same stories. Brady’s grandparents had both played a role in the North-West Resistance. His grandfather Laurent Garneau was part of the Red River Resistance and a spy for Riel during La Guerre Nationale. His grandmother was Eleanor Garneau, the woman who had saved her husband by washing Riel’s incriminating letter into the family laundry. Brady’s grandfather was saved from death, but his association with Riel and the Métis Nation had consequences for the rest of his life. In 1892 Garneau was elected to the North-West Territories Parliament in Regina but was never allowed to take his seat because of his previous involvement with Louis Riel. Brady and Norris were born and raised as Métis nationalists.

THE ALBERTA MÉTIS MOVEMENT

The Métis Nation was never a simple entity. There had always been northern and southern branches. There were the English Métis and the French Métis. There were urban Métis and rural Métis. There were the buffalo hunters and the canoe brigades and the farmers. The Nation has always been a fluid mixing of these various languages, religions, geographies and economies. Now there were added complexities. By the 1930s the Métis Nation on the prairies was sharing its cultural space with a new group.

Since the late 1800s the government had been slimming down the numbers of Indians on its Indian Act registry. Many were forced out when they began to partake in the basic benefits of Canadian society—voting, education, joining a profession, marrying a non-treaty man, etc. They were called non-status Indians, referring to the removal of their “status” from the Indian Act registry. Non-status Indians found themselves in similar circumstances to the Métis Nation: they were landless and destitute. Together, the Métis and non-status Indians in the Prairies numbered some ten to twelve thousand, about a third of which were non-status Indians.

The non-status Indians didn’t share the same Métis history, didn’t see themselves as part of the Métis Nation and were not animated by the nationalism that defined the Métis Nation. The Métis referred to themselves as “Otipêyimisowak,” which was not a term the non-status Indians ever adopted. The government crudely lumped all of them together into one box labelled “Métis and non-status Indians.” But they were fundamentally different.

The Alberta Métis were still nomads. Most of them now lived in the northern parts of Alberta. They no longer followed the buffalo herds, freighted or traded. They lived in a seasonal round, moving to access resources that provided a subsistence living from hunting, fishing and trapping. The Métis, who had previously travelled thousands of miles in a year, now had a much-reduced territory in northern Alberta and Saskatchewan. Some Métis, mostly those from the southern parts, lived on small farms or worked for wages, living the life of itinerant labourers. There were Métis ranchers, some city dwellers and a few businessmen. But since 1885 the Métis had mostly put their heads down and practised avoidance.

It was another massive transfer of land jurisdiction that ignited the Alberta Métis. Until the late 1920s Crown lands in the Prairies were still federal lands and were still available to the Métis. But in 1928 the federal government began the process of transferring control of Crown lands to the three Prairie provincial governments. This transfer, like the transfer of Rupert’s Land and the North Western Territory in 1870, threatened to undermine the Métis again. The provinces were going to open the lands up for homesteading.

The Alberta Métis movement began at Fishing Lake, a small Métis community in the forest just west of the Alberta-Saskatchewan border and about forty miles east of St. Paul des Métis. When the Métis at Fishing Lake learned about the plan to open up their area for homesteading, they understood that once again their occupation would not be recognized and they would lose their lands. By this time the Métis had had long experience with this particular show. There would be the government declaration about available land, then there would be surveys and, before they knew it, strangers would be claiming their lands. The government would do nothing to protect the Métis as prior occupants and they would be pushed out. It was an old story and everybody knew the plot.

Fishing Lake held meetings—lots of meetings. One of the ideas they discussed was an exclusive Métis reserve. They talked about a Métis reserve so much that word got out on the moccasin telegraph. There were rumours of families who wanted to come from Saskatchewan, southern Alberta and Montana. According to one Métis, Old Cardinal, it was all talk and no action. No one took the reins and pushed their protest forward. It was just like in Red River before Louis Riel gathered the forces. Needing some help, in 1930, the Métis of Fishing Lake approached Joe Dion, who was a schoolteacher at a nearby Indian reserve. Dion had lots to recommend him to the Métis. He was a nephew of Big Bear and he was a non-status Indian. Dion agreed to help. Over the next two years, more meetings were held and they began to attract more people.

They drafted several resolutions requesting land and a meeting with government. Then, in the summer of 1931, hundreds of Métis from communities all around Fishing Lake met on the shores of Cold Lake. At the meeting the Métis appointed a council, drafted a petition and collected over five hundred names. The petition set out their belief that they had some rights to the land. They would not interfere with anyone and were not asking for improvement from government. They wanted the right to occupy the land. A delegation was selected to meet with the Alberta provincial government. In response to the meeting, Alberta drafted a questionnaire it wanted the Métis organization to distribute. It was a tacit recognition of the Métis as a group with an issue that needed some attention. Dion worked at getting the questionnaire filled out by as many people as possible, and in this task he did not work only with the Métis; he also had non-status Indians fill it out.

More meetings throughout 1932 brought up other issues, such as hunting and fishing rights, health conditions, the lack of schools and jobs, and the denial of relief to destitute Métis. Dion travelled from community to community, encouraging discussion and holding meetings. They decided to hold a province-wide convention in December.

Dion was a kind, intelligent and helpful man, but he was as naive as Riel about politics. He believed facts would sway government. He believed that once government understood how many Métis and non-status Indians wanted and needed land, it would be granted. But government rarely acts on the basis of need, want, facts or logic. It was the brewing scandal of thousands of destitute provincial citizens and the frequency and size of the Métis meetings that caught the government’s attention. Some say Alberta was shamed into action. But shame is a garment that government usually wears quite well. More likely they were getting votes by promising action on the Métis “problem.”

Dion was no politician and he knew it. Enter Jim Brady, the Métis strategist, with his first advice to Dion: the Métis must be formally organized and they needed to build an organization in each community with strong leadership. Brady drafted a constitution for a new province-wide Métis organization “formed for the mutual benefit and the interest and the protection of the Métis of the Province of Alberta . . . a non-political and non-religious society, having as its sole purpose, the social interest and uplifting of the members of the Association and the Métis people of the said Province of Alberta.”1 There were self-government provisions that set up an executive council of the association as the governing body of all Métis on hoped-for land reserves. By this point they had organized with twenty-five elected councillors and a constitution. Meetings were held in other communities. Petitions were drafted.

By the time the December convention was held, the Métis had the trio of leaders they needed: Dion the community organizer, Brady the intellectual and political strategist, and Norris the dynamic speaker and agitator. Norris was the man who revived flagging Métis spirits, reminded them of Métis nationalist history and linked the movement to its past. He gave the Métis hope.

By December 28, 1932, the Métis Nation had officially organized in Alberta as L’Association des Métis d’Alberta et des Territoires des Nord Ouest.2 In English they were known as the Métis Association of Alberta. They had one simple goal: land. They believed it would give them the ability to provide for their homeless and destitute families, education for their children and better medical attention. They knew land was something the Alberta government had available to give them. Money during the Depression was hard to come by, but land was readily available, especially in the northern parts of the province, which were not best suited to farming. They sent a brief to the Alberta government setting out eleven areas they wanted for Métis settlements.3

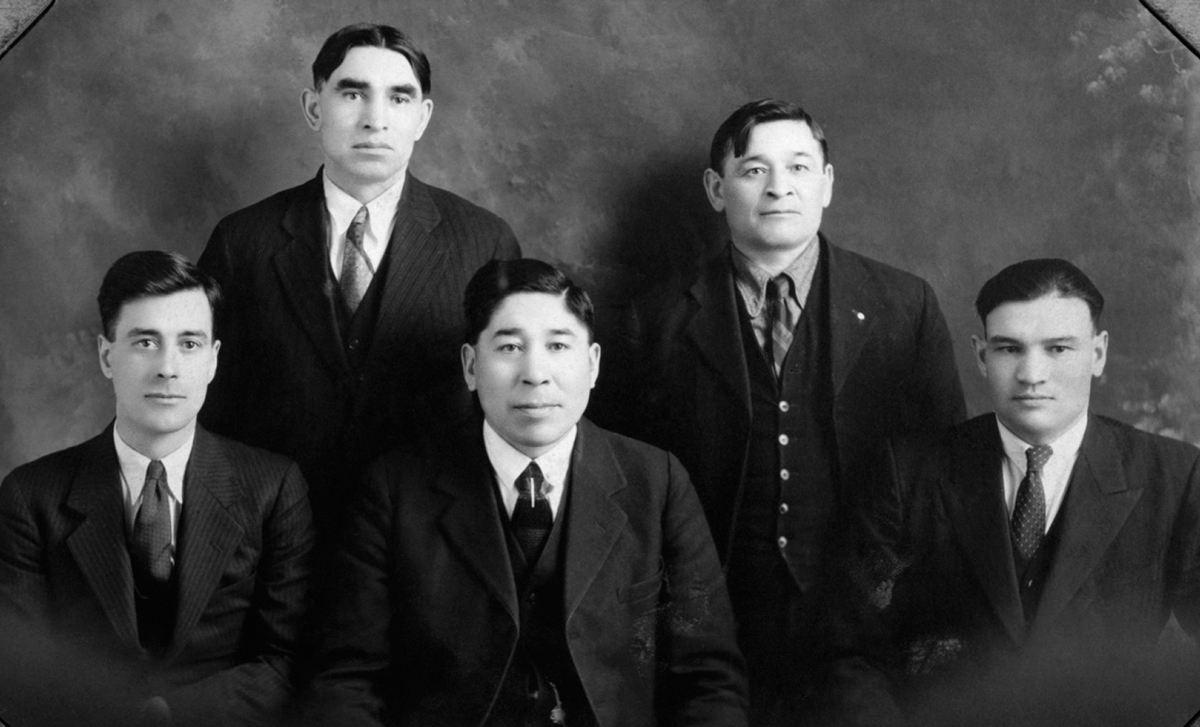

The executive council of the Métis Association of Alberta, 1935. Front row, left to right: Malcolm Norris, Joseph Dion, James Brady. Back row, left to right: Peter Tomkins, Felix Callihoo. (Glenbow Archives PA-2218-109)

The new Métis organization also dealt with the identity and naming issue. Never again would they use the odious term “half-breed.” Henceforth they would be known only as the Métis. Despite its name, the Métis Association of Alberta was not a Métis-only entity. To be eligible for membership a person had to be “Métis, or of Métis descent, who is a pioneer of Indian descent and their descendants, within the limitations of the Old North West Territories, the present North West Territories, the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, or a non-treaty Indian having the above qualification or treaty Indians becoming enfranchised . . .”4

The identity issue was a wedge that the government exploited. When Dion stated that those in most need were treaty Indians who had been enticed to take scrip, he fed into the province’s argument that the responsibility really lay with the federal government. Thus, he stirred up the issue of whether Métis were a federal or provincial responsibility, an issue that would plague the Métis until 2016 when the Supreme Court of Canada finally declared all Aboriginal peoples in Canada a federal responsibility.5 But before that decision, for eighty-five years, the provinces and the federal government played what has often been described as a game of jurisdictional football with the Métis. Football is an entirely inappropriate description of what went on. In football, both sides want the ball. This was a game of jurisdictional hot potato. In the 1930s the hot potato game was in full swing. Alberta formally requested federal participation in the discussions about Métis land claims and was firmly rejected. The Métis, as far as the federal government was concerned, were a provincial problem.

In 1932 the new Alberta Métis organization declared itself a “non-religious society” and ended a century of domination by the Catholic Church when it removed the Church’s control over Métis education. This would have a profound effect on Métis for the future. For a while the relationship with the Catholic Church remained strong, in large part influenced by the fact that Joe Dion was a staunch Catholic and defender of the Church. But a change had taken place. The priests recognized that the association had influence and they now sought its assistance.

The churches educated a few Métis children out of charity, but 80 per cent of the Métis children in Alberta were growing up without any education, a number Métis leaders believed was likely an underestimate. There were no public funds provided as there were for treaty Indians and white children in public schools. It was against the law for children not to be in school, but neither the federal nor the provincial government would accept responsibility for Métis children if they lived on Indian reserves. There simply were no schools in the remote areas where many Métis lived, and many Métis were still migrating seasonally. Their children rarely, if ever, went to school.

The Métis association began to press the Alberta government to authorize setting aside the lands they had selected. Amendments were made and new areas were added as Métis from other parts of Alberta began to participate, including some families evicted from their lands when Jasper National Park was established. The Métis continued to organize throughout the province. By 1935 there were forty-two local Métis associations. They had only rough data, but by their estimates there were some ten to thirteen thousand Métis in Alberta, although not all of them were members of the association. Five thousand Métis needed relief.6

Meetings—that’s how they did it. They met repeatedly. They talked and talked again. Despite Old Cardinal’s thought that talking was not doing, the meetings were what had always brought and kept the Métis Nation together. Meetings kept them focused and, as in all oral cultures, kept them knowing each other, knowing their history and knowing they needed to stay together to better their people. In this sense what was happening in Alberta was identical to the North-West Resistance and the Red River Resistance. It was the voice of the Métis Nation hauling itself meeting by meeting out of le grand silence.

Brady and Norris wanted to unite the Métis Nation. They looked beyond the Métis in Alberta and kept communications going with their brothers and sisters in other provinces. The Alberta Métis passed a resolution at their convention stating that it “fully supports and endorses the efforts of the Saskatchewan Métis Society to establish their Legal and Constitutional rights and our Secretary be instructed to convey fraternal greetings to their forthcoming Convention.”

They didn’t want the Métis to be seen merely as destitute people needing relief. They would use that label if they had to, but for Brady and Norris, their movement was always about the Métis Nation and its need for land and self-government. There was no battle for the political left or the right—nothing like that—just a struggle for land, resources and self-government. That’s what Grant, the Riels and Dumont had fought for.

Brady set out a hierarchy of tactics to achieve their goals: organization, direct pressure on government (by way of petition and the courts), and voting power in mainstream politics—in that order. Brady believed that if petitioning failed, they could resort to the courts. But court is not a sure thing even in the twenty-first century. Back in the 1930s going to court would have resulted in a certain loss. Resorting to the use of political power was also chancy, because with the rapid immigration in the Prairies, the Métis had become a minority group. They spent a lot of time petitioning, but it really accomplished very little. So, despite Brady’s tactical hierarchy, he knew they really only had one tool—organizing.

Pete Tomkins joined Dion, Norris and Brady and they became affectionately known as the Big Four. The Church put great effort into dividing the Big Four. Bishop O’Leary issued dire warnings in the press about radicals and tried to use Dion’s Catholicism to separate him from the other three. But the Big Four wanted to avoid an outright fight with the Church. It was simply too powerful. So, Brady, Norris and Tomkins decided to ask Dion to neutralize the Church’s efforts. Norris wrote to Dion:

An article appearing in the press a couple days ago emanating from Bishop O’Leary’s palace warns all clergy + Catholic people to beware of organizations + individuals express[ing] radical ideals. Good God Joe, if it is radical to tell the truth about the conditions prevailing among our people and to advocate a rehabilitation of Métis then I am, you are, we are all Reds. If this is Christianity then I would prefer the beliefs + traditions of our Indian antecedants of a Happy Hunting Grounds in preference to the heaven + God as advocated by the clergy. I dread open opposition of the Clergy for they are too influential. Will you therefore write to Bishop O’Leary stating you have seen this article and are greatly concerned lest the Métis Association be considered as being Red.7

When Dion lamented their lack of Riel, Norris objected: “Joe we have plenty Riels and [it] only requires a little fanning of a spark that would become a flame.” In urging Dion to throw himself more forcefully into the battle, Norris said, “We are behind you if it means a fight, throw your coat away, ours are already off and we are ready.”8

THE EWING COMMISSION

By 1934 the Big Four had put so much pressure on the Alberta government that a royal commission was appointed to inquire into the conditions of the Métis. The Métis Nation had already been the subject of several commissions of inquiry. There was the Coltman Commission after 1816, and there were commissions after the Red River Resistance and another after the North-West Resistance. There were inquiries into scrip, Bremner’s furs and into the children’s land grants in Manitoba.

This new one was called the Ewing Commission, after its chief commissioner. The appointment of the commission was either the desperate last gasp of a party heading into a close election and needing Métis votes, an inquiry into just why the pesky Métis had not already been assimilated, or a way to pathologize the Métis as a disease that required a cure. Racism was the common factor. Either way, it would take time, and since all commissions only make recommendations, its findings could either be acted on fully, partially, or left to gather dust on a shelf. The political winds blowing when the report was released would determine its use.

But it was an opportunity for the Métis. Brady and Norris prepared written submissions but feared the commission would degenerate into a relief analysis. The only way they thought they could counter that was to present the history of the Métis Nation and to demonstrate the current state of the Métis economy as something that could be reversed. Since it seemed the Alberta government was prepared to set land aside for the Métis, the real issue for the Big Four was to get the commission to recommend that land be set aside under the control of the Métis Nation with the necessary political authority to govern their people. In their 1935 brief to the commission, they began by asserting that improvements to the economy and security of the Métis Nation required “the completion of our unification with the Canadian nation.”9 They went on to explain:

The history of the Métis of Western Canada is really the history of their attempts to defend their constitutional rights . . . It is incorrect to place them as bewildered victims who did not know how to protect themselves against the vicious features which marked the penetration of the white man into the Western prairies.

We are on much firmer ground when we refer to the glorious tradition of the Métis in fighting for a democratic opening of the West.

But Ewing did not want to hear about Métis nationalism and refused to let Norris present his case fully. There would be no discussion about Métis nationalism, rights, unity or history, and no discussion about the Métis who were successful. Métis, in the commission’s eyes, were poor individuals and their destitute state was their own fault. They were a pathological problem, an illness that needed fixing. The commission wanted to hear about disease, lack of access to education, and poverty. Nothing more. Containment, oversight and assimilation were the cure for the disease of being Métis. It was exactly what the Big Four had hoped to avoid. The Métis idea of self-government over its own land base died before it was born.

In 1938 the Metis Population Betterment Act passed in Alberta. It gave effect to the recommendations of the commission. The lands set aside were for those Métis who were unable to support themselves. The Métis Association of Alberta tried to include at least one settlement in central or southern Alberta and a settlement at Grand Cache for the Métis families who had been evicted from what was now Jasper National Park. Both requests were rejected. It was not that there were no Métis in the south, but the government wanted to keep the Métis reserves away from the settlers. The Métis were encouraged to move north. In the end twelve Métis settlements were created: Fishing Lake, Elizabeth, Kikino, Buffalo Lake, East Prairie, Gift Lake, Peavine, Paddle Prairie, Marlboro, Touchwood, Cold Lake and Wolf Lake.

Although councils were set up on the settlements, the government moved quickly to increase its own control and diminish the size of the grant of land and powers. It redefined “Métis” by adding a blood quotient requirement. Henceforth Métis were persons with not less than a quarter of “Indian” blood. The minister granted himself many administrative powers and the administration was placed into the hands of a provincial government department. In 1952 the government granted itself the power to appoint the majority of councillors on each settlement council. Two settlements, Marlboro and Touchwood, never really got off the ground. Then in 1960, as part of its plans to establish the Primrose Lake Air Weapons Range, the province unilaterally took back two of the settlements, Cold Lake and Wolf Lake.

Alberta set up the Métis settlements to owe their jurisdiction, authority and power to the province. Funding was the tool Alberta used to undermine Métis self-government. It controlled the direction of the settlement governments when it funded its preferred objectives, and cut or denied funding when a proposed initiative didn’t suit its purposes. Despite the problems, there were eight Métis settlements in Alberta. To this day they are the only Métis land base in the Métis Nation.

The Big Four succeeded in getting land, but in the process the Métis Association of Alberta was sidelined. Norris and Brady withdrew and both signed up to go overseas. The Second World War was about to engulf them all.