THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Métis Nation men played a prominent role in the Second World War. The South Saskatchewan Regiment, the Regina Rifles and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles had large numbers of Métis soldiers. Métis soldiers enlisted in the navy and in the air force. They took part in many of the main engagements in the Second World War.1 Some, like Vital Morin, Frank Goodon and Roger Teillet, were prisoners of war.

In many Métis communities, virtually the entire population of healthy young men signed up. Why did they sign up? When the Second World War began in September 1939, the Métis were living on the margins of society, subjugated economically and culturally. Their history of resistance had not endeared them to their new neighbours. They were landless and many were still migratory. It was this grinding poverty and alienation that motivated Métis men to sign up in such large numbers. Even the poor army pay was more than twice what they could make by other means. Many hungered for acceptance, for the camaraderie and for the chance to show people that they had some worth. During the war they proved themselves to be loyal warriors.

They did not completely lose sight of Métis Nation issues in the long years of the war. Jim Brady took the opportunity to visit Marcel Giraud in Paris in 1946. Giraud was an anthropologist working on a massive anthropological study of the Métis Nation, Le Métis Canadien. When Brady was on leave, he spent five days reading the proofs of Giraud’s thesis, which to this day is still the most complete anthropological study of the Métis Nation. For the most part during the war, however, the energy that had been building in Métis Nation organizations dissipated. Too many of the young men were gone, and those left were simply struggling to survive.

The boys who went overseas came back with a new set of eyes. They had seen Europe and they had taken part in the brutal carnage of the war. They came home with new ideas and a greater understanding of politics and power. The arrival of the men back from overseas was the catalyst for a new wave of Métis activism and nationalism. The Old Wolves were gone now, and it was their grandsons, veterans of the war, who took up the battle of their fathers and grandfathers.

It wasn’t a new starting point for the Métis. They had never lost sight of the Métis Nation. But it was a new starting point for Canada’s transformation. In the aftermath of the Second World War, a massive experiment in humanity began, one that is still happening. This is the human rights wave born in the horrors of the Second World War. It came from a profound belief shared by men and women all over the world after the war—the new understanding that all people deserve to be treated with dignity, that we are all human, and that there is no honour and never an excuse for oppression based on race, religion, culture or colour. The sense then was: Never again! We won’t let this happen again. We will not stand by. We will create universal norms, customs and laws to ensure human dignity is protected. We will work together as United Nations, and the world will change for the better. Canadians wholeheartedly embraced this new world view. It was a profound shift from the beliefs and attitudes that had been used for so long against the Métis Nation.

On an individual level, the Second World War changed our Canadian soldiers. Indigenous men signed up for service in unprecedented numbers. And non-Indigenous Canadian boys, most for the first time, actually met First Nation and Métis boys. They fought together and they were forced to depend on each other. They learned that they had the same fears, the same courage and the same loves, and they learned to engage in a common cause. After that, it was difficult for those non-Indigenous Canadian boys to come home and pick up their old prejudices.

This is when the modern Métis rights movement started. The seeds were sown in the soil of horror—when Canadians looked at what happened, knew it was wrong and knew it must change. Thus began, among many other things, the United Nations, the American civil rights movement, the American Indian Movement and, as part of that wave, the Indigenous rights movement in Canada. It took a while to get going. Such fundamental change doesn’t happen overnight.

THE ROAD ALLOWANCE PEOPLE

Since at least the 1930s, governments in the Prairies had believed they had a “Métis problem.”2 As the press repeatedly reported, the Métis were a “hard people with whom to deal. They are wanderers . . . and the big trouble is that there are so many of them.”3 In 1949 government officials from Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan met to discuss the Métis “problem.” The problem, as they saw it, was the economic and cultural situation of the Métis, who were plagued by a high level of illiteracy, destitution, infant mortality, and poor diet and health. They saw two foundations for the problem: the nomadic life of the parents, and the discrimination by local officials. Rights and nationalism never entered the discussion. In short, the Métis needed “improvement.”4

One of the big problems was the lack of land recognition. As the immigrants had moved in and taken over the land, the Métis were called “squatters.” Land they had long called their own was now “owned” by people with pieces of paper. Possession and occupation, long the standard for common law ownership in English law, was not the law of Canada. Ownership was proven solely by official paper. Having lost their lands to the speculators through the survey, homestead and scrip processes, the Métis lived wherever they could as long as they could, and then, when pushed off their lands, they moved to the public lands available along railroads, roads and Crown lands. There, they built cabins and took on yet another name: the “road allowance people.”

The route to life on the road allowances varied. Rita Vivier Cullen was born in 1936. Rita’s grandparents arrived on the road allowance on the run from the authorities in North Dakota. The men were gone on a hunting trip when the authorities took all the children away to residential school in Walhalla (formerly St. Joseph). When the men returned home to find their children gone, they headed to the school. Holding the nuns at gunpoint, the Vivier men reclaimed their children and ran with their families over the border toward St. François Xavier. They settled on the road allowance beside the Assiniboine River. Rita lived with her family in a one-room log house. The floor was mud with braided rag rugs. The exterior was whitewashed every summer. Her grandparents lived across the river in their own log cabin. Rita remembers it as a nice, cozy little place.5

Maria Campbell (Women of the Métis Nation)

Maria Campbell, a respected Métis Elder, author and another road allowance child, painted a completely different picture:

So began a miserable life of poverty which held no hope for the future. That generation of my people was completely beaten. Their fathers had failed during the Rebellion to make a dream come true; they failed as farmers; now there was nothing left. Their way of life was a part of Canada’s past and they saw no place in the world around them, for they believed they had nothing to offer. They felt shame, and with shame the loss of pride and the strength to live each day. I hurt inside when I think of those people. You sometimes see that generation today; the crippled, bent old grandfathers and grandmothers on town and city skid rows; you find them in the bush waiting to die; or baby-sitting grandchildren while the parents are drunk. And there are some who even after a hundred years continue to struggle for equality and justice for their people. The road for them is never-ending and full of frustrations and heart-break.6

One of the Métis Nation leaders of the 1970s and 80s, Jim Sinclair, was born on a road allowance in Saskatchewan in 1933. He grew up in a slum shack, and when the authorities evicted his family from the shack, they moved to a tent city farther away from the town. In 1950 Jim’s parents moved to the “nuisance grounds” on the outskirts of Regina. The nuisance grounds constantly shifted as Regina expanded. “Nuisance” was how Regina thought of the slum. In fact, it was a Métis tent city in a garbage dump.

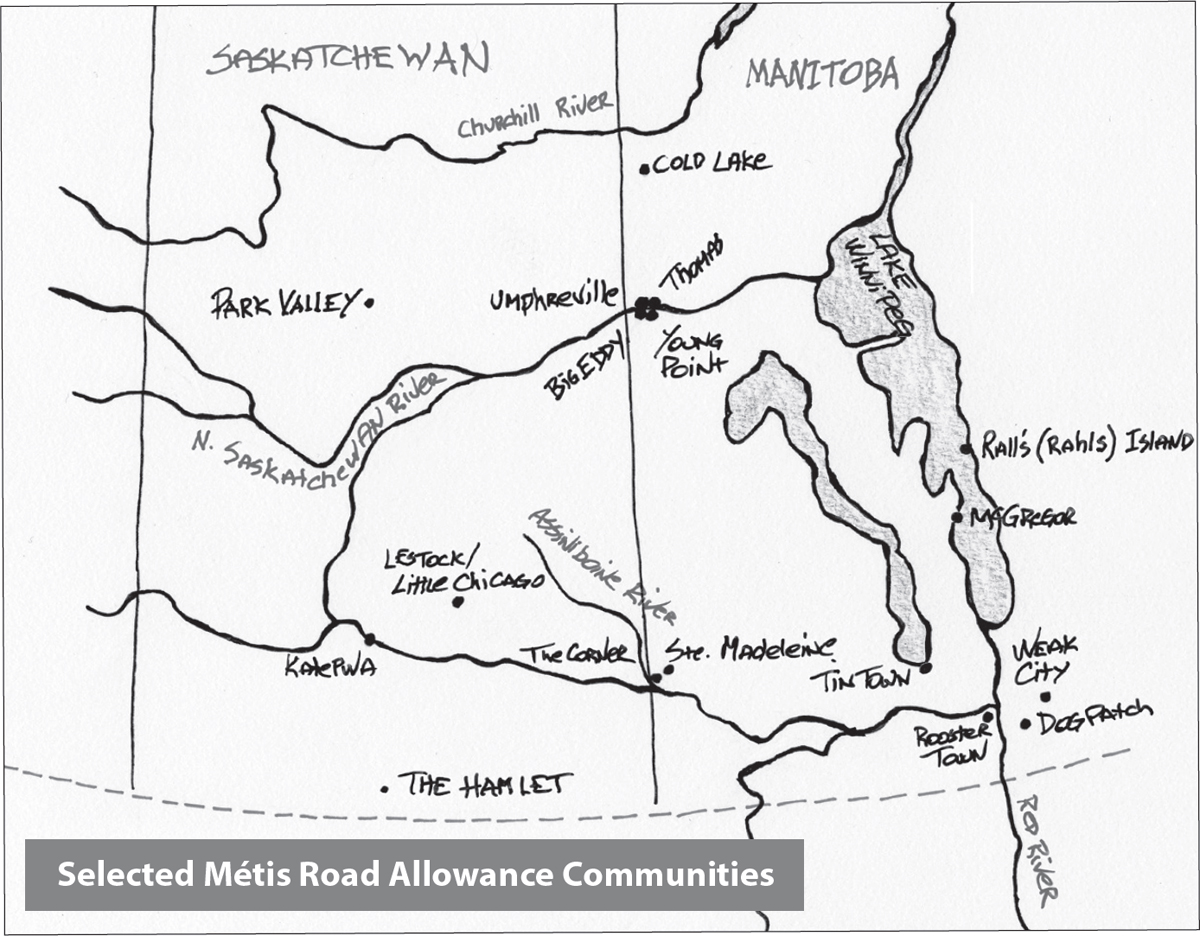

There were many Métis shantytowns and road allowance communities in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In the 1950s there were twenty-six such settlements in Manitoba, identified by the government as fringe settlements with a slum mentality. They were typically unserviced areas on urban edges, with colourful names like The Big Eddy, Tin Town, Little Chicago, Dog Patch, The Corner and Rooster Town.

ROOSTER TOWN

As far as the good (non-Indigenous) people of Winnipeg were concerned, Rooster Town was nothing more than squalor and filth. Its Métis residents had no morals and they were all shiftless and lazy. Rooster Town’s Métis were Winnipeg’s untouchables. Parents warned their children never to touch Métis children from Rooster Town. You might get a disease if you did.

Winnipeg of the 1950s wanted to present itself as a city that was not plagued by disease-ridden, poor Métis. Certainly, they didn’t want what amounted to a village of them so close to the centre of town. It was much too close for comfort. The urban land they were occupying was far too valuable to be used for a Métis shantytown. The Métis were not Indian enough to be acknowledged as having land rights, and they were too Indian to benefit from any policy other than slum clearance. One thing was certain: they were not wanted in the city.

While the conditions of Rooster Town were poor, it housed a community of several hundred Métis at its height in the 1930s. It provided shelter from the storm of abuse and prejudice the Métis faced when they left their town. Their attempts to preserve their community meant that Rooster Town was a shifting location. They moved and they moved again, always farther south and west until finally, in the 1950s, Winnipeg turned the whole area over to developers.

In 1959 the fourteen families still living in Rooster Town were evicted and given seventy-five dollars to move out by May 1 or fifty dollars to move out by June 30. The Métis were fairly quiet and resigned about the evictions. They had seen it coming and it was what they expected. Today the Grant Park Shopping Centre and Grant Avenue run over Rooster Town. Ironically, both are named after Cuthbert Grant, the first leader of the Métis Nation.

Rooster Town, 1959 (Gerry Cairns/Winnipeg Free Press)

STE. MADELEINE

Ste. Madeleine was a Métis settlement located just southwest of Russell, Manitoba. It was a logical place to settle because it was well known to the Métis. It was on the route the Métis travelled to get to the buffalo herds, and it later became part of the Carlton Trail. It was also near important Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts at St. Lazare and Fort Ellice. Ste. Madeleine was one of the refuge places where Métis landed when they fled from the reign of terror during the 1870s. Many of the families who settled in Ste. Madeleine were originally from Baie St. Paul, St. François Xavier and St. Norbert. Another wave of Métis arrived after the North-West Resistance. By 1935 there were about 250 Métis in Ste. Madeleine.

Many were itinerant labourers working for the nearby white farmers. As we have seen elsewhere, the Métis were not commercial farmers. Every family had a vegetable garden, but they mostly used their lands as scrub pasture for their few cows and horses. It’s just as well that they didn’t try to commercially farm the land, because it was sandy soil and would have made for very poor grain crops. Over the years the lands were subdivided as fathers handed over parcels to their grown children. The effect was that a uniquely Métis settlement was created. Because of the family connections in Red River and Saskatchewan, it was well known throughout the Métis motherland. Despite the fact that many had been there since the 1870s, the Métis in Ste. Madeleine didn’t own their lands. The few who had acquired homestead lands were never able to pay their taxes.

The 1930s, the Dirty Thirties, were a terrible time on the prairies. There were serious droughts, and soil drifted for hundreds of miles. The winds and the drifting soil created blinding storms that obliterated the skies. The force of the wind was such that the impact on skin left scars. The problem was the farming practices. Farmers left the bare soil of their plowed fields open to the wind. Much of the land should never have been plowed at all because the soil was simply too poor and there was not enough water. This was the bald prairie that nobody wanted as homestead lands in the 1870s. But the introduction of new wheat species had led the government and homesteaders to believe that any land on the prairie would do. It was a huge mistake.

In 1935 Ottawa passed the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act (PFRA). It was Ottawa’s attempt to deal with the drought and the drift of soil. The idea was to seed the bare soil with grass for grazing. In a story we are brutally familiar with by now, they began with a survey. Three years later the survey was complete and community pastures were designated. Ste. Madeleine was to be one of the community pastures.

The basic theory of British and Canadian common law is that no person can be deprived of his or her land without compensation, and this was the theory adopted under the new act. Homesteaders whose land would become community pastures were offered full compensation or good farming land in exchange for their sandy soil. They were also offered assistance to relocate. But everything depended on whether they had paid their taxes.

In Ste. Madeleine, a community where Métis had been living since the 1870s, few people had ever been able to pay their taxes, and by the 1930s those taxes would have been more than the property was worth. It didn’t really matter how much the taxes were; the Métis in Ste. Madeleine had no possible way to pay them. That meant the government could order the destruction of their homes and community with no compensation and no thought for what the people would do or where they would go.

That is exactly what happened. The government paid the locals $60,000 to do the dirty deed, and the locals did it for the money and the jobs. One of the locals provided his perspective: “Everybody wanted jobs. They wanted the PFRA to bring jobs in . . . Lets get them bloody Breeds out of there and have some work. Let’s give them a few bucks and chase them out of there . . . Everybody was for that.”7 Métis houses were burned and their dogs were shot while they watched. Ironically, because the Métis were not engaged in commercial farming, they didn’t leave their land with exposed soil and were not contributing to the soil erosion problem on the prairie. Their small farms didn’t need rehabilitation, and the $60,000 paid to the locals was probably more than what the Métis properties and back taxes were worth.

Ste. Madeleine lives in the memories of the Manitoba Métis, another story in the long dispossession of the Métis Nation from their lands. One of the consequences of this long dispossession is that the Métis have maintained their mobility. Canada went to great trouble and expense to stop First Nations from pursuing their mobile lifestyle. They were settled on reserves. Today First Nations move less than any other people in Canada. But all actions taken by the state—the scrip process, the dismantlement of the communities the Métis created, the refusal to recognize their collective identity—all contributed to the Métis’ ongoing mobility. Today the Métis on the Prairies are still mobile. We know poor and young populations are highly mobile, but even taking those factors into account, the data show that Métis on the Prairies are significantly more mobile than the non-Indigenous population.8

SASKATCHEWAN

Like the Métis in Alberta, the Saskatchewan Métis became divided into northern and southern branches. The Métis in southern Saskatchewan reorganized, and by 1929 l’Union Métisse du Local #1 de Batoche resolved “de s’organiser suivant plus au moins la constitution Métis du Manitoba.”9 In July they held a conference of the Union Métisse Nationale. In attendance were delegates from the métisse de Manitoba. Also at the assembly were the Union Métisse de la Saskatchewan and les gens Métisse. They resolved to form a Union Métisse Nationale l’Ouest and to adopt the flag of the Manitoba Métis “comme drapeau de l’union Métisse de l’Ouest.”10 By 1930 the Métis women in Saskatchewan were organizing as well. But the national organization never got off the ground, and the southern Saskatchewan organizational machine held a few meetings and then slumbered.

Green Lake was an exception. Alex Bishop was the local president. He kept the local in Green Lake alive. And it was Bishop who awoke the Métis national consciousness in the north. During the fight to establish the Métis settlements in Alberta, Bishop had kept in touch with Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris. The links were there but they were fragile. Then, after the Second World War, Brady and Norris arrived and set about trying to revive the spirits of the Saskatchewan Métis.11 It was not an easy thing to do.

The Métis in northern Saskatchewan were quite different from their relations in northern Alberta. The Métis in northern Alberta had never lost their national consciousness. But the Métis in northern Saskatchewan had little to connect them to their southern Métis family. The freighters and boatmen who had provided the links were now trappers, hunters and fishermen who didn’t travel back south. They had grown isolated in the north. They followed a seasonal round, and the communities were a temporary rendezvous before the families went back out on the round again. Any vestiges of the Saskatchewan Métis Society were in the south.

In the 1940s Saskatchewan set up an experimental farm project for the Métis. The Saskatchewan government, following Alberta’s lead, stressed that it was working to relieve present conditions, not addressing past injuries or rights. One of the experimental farms was set up at Green Lake, where each Métis family received forty acres of land with a ninety-nine-year lease.

Most of the Métis who ended up on the Green Lake farm came from the south. Many came from the area just north of Qu’Appelle. Métis families were bundled onto trains, and as the train departed for Green Lake, the people watched as men set fire to their homes. They were supposed to be going to a new home. But there was no housing when they arrived, and the land was heavily wooded and would take ages to clear. The lots were too small for commercial farming. The Green Lake farm was supposed to be a relief measure, but there was no relief. There was nothing to support them while they got on their feet. The southern Métis had simply been shipped north and left to fend for themselves in a land they didn’t know. They were ill-equipped, had little by way of farming skills and they had no equity in the land. Most of them left.

The 1950s saw little action on the Métis political front in Saskatchewan. But things started to change in the 1960s. In 1961 the Métis organized a commemorative service at Batoche. Both Norris and Brady attended. It was a small service with about thirty or forty attendees. The next year, 1962, the government invited Norris to speak at another commemorative service at Batoche. It was sponsored by the Royal Regiment of Canada and was supposed to be a step toward reconciliation. Norris was expected to be grateful for the opportunity and to make nice. Instead he gave them a history lesson, and it was not the history they knew.

The event was called a service “To Honour Those Who Fell in the Saskatchewan Rebellion of 1885.” If the Old Wolves had still been around, they would have objected to the use of the term “rebellion.” Norris did not hesitate to set the record straight. He called Riel a patriot who waged a battle similar to the battles fought by William Lyon Mackenzie and Louis-Joseph Papineau. He objected to the monument at Fish Creek that misstated the facts. It called the Métis rebels and said they had been defeated when in fact they had held off the army against overwhelming odds. Norris blasted them all and finished by telling them that the conditions of the Métis Nation were “a blot on our country.” Then he led them to Gabriel Dumont’s grave and unveiled a new monument. It was a classic Métis speech. He made them uncomfortable. He told them they were wrong, told them what they should be thinking and doing, and then staged his own event.

Métis leaders all learned from Norris how to stage these kinds of events. Another Saskatchewan leader, Jim Sinclair, also had a flair for staging events that grabbed attention. When Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) gave the Saskatchewan Métis Society a meagre $5,000 for a housing program, Sinclair had the entire amount converted into nickels and dimes and carted in wheelbarrows into the CMHC offices in Regina. He dumped the huge pile of coins on the floor. The Métis, he told reporters, were fed up with nickel-and-dime programs.

Sinclair’s nickel-and-dime stunt has become a well-known story among Métis activists. Tony Belcourt, the president of the Métis Nation of Ontario in the early 1990s, knew Sinclair well and loved the nickel-and-dime story. He told that story when he was considering liberating the noose that was used to hang Riel. At the time it was on display at Casa Loma in Toronto. Belcourt was disturbed that the RCMP were displaying the noose in Ontario. It was a nasty reminder of the way John Schultz and Charlie Mair had displayed rope they claimed had been used to bind Thomas Scott. They had used such props in Ontario to stir up the Orange Lodge. What did the RCMP intend by displaying in Ontario the noose that hanged Riel?

Belcourt thought that liberating the noose from Casa Loma could be used to generate a grand discussion about Métis rights. He would welcome a debate, maybe even a trial over whether the Mounties had any right to keep and display the noose that hanged Riel. Belcourt never did move forward with that plan, but it was the kind of stunt Sinclair and Norris would have admired. Decades after the nickel-and-dime stunt, another Saskatchewan Métis leader, Clément Chartier, was so frustrated at being limited to observer status in a meeting that he went to it with a black piece of fabric tied like a gag over his mouth.

Imagine the pile of nickels and dimes that cascaded onto the floor, the look on the housing officials faces and the noise of the metal coins. What a scene it must have been! And when Chartier sat through a meeting with a black cloth over his mouth, the message was clear. It is often difficult to get attention for Métis issues, and these leaders taught the Métis Nation that the government and press respond to dramatic gestures—the government with embarrassment, and the press with glee. The Métis Nation has never been above turning up the volume on the government embarrassment knob.

MANITOBA

By the 1950s the term “Métis” was a dirty word in the Prairies. Some shied away from the identity because of the prejudice they experienced. There was little advantage to claiming Métis heritage and much to be lost—housing, jobs and even love. Meanwhile Prairie governments continued to seek solutions to the Métis “problem.” The ideas adopted by the Ewing Commission and the Saskatchewan government now took on a new name: community development. This movement purported to both decolonize and fight poverty. Essentially, the idea was to help people help themselves.

The government of Manitoba eventually commissioned a study of the Métis problem.12 The 1959 Lagassé report enumerated 23,579 Manitoba Métis and called for integration. By this, Jean Lagassé said, he did not mean assimilation. Lagassé claimed that he was not looking to blend the Métis into Canadian society to the point where their culture disappeared. Lagassé thought it was possible to integrate to a point where there would be a “harmonious interaction of social or cultural entities that retain their identity.”13 The role of the state was to promote that movement through self-help but based on a respect for the Métis as an ethnic group having civil and human rights. The distinction between integration and assimilation was the kind of subtlety that academics appreciate, but it proved to be virtually impossible to incorporate into government programs.

Lagassé’s report was a product of its time and reflected his Catholic leanings and morality. His attitudes toward Métis history (rather romantic), Métis women (too promiscuous) and the Métis way of life (unremitting poverty) came through loud and clear. The Métis were immoral, according to Lagassé, because Métis women actually liked sex. Some reports reveal more about their author than about the subject of the study.

His proposed solutions were impractical. He believed that relocation to urban centres was the best long-term solution to Métis poverty. We should be clear about what he was proposing here: mass relocation of all Métis and non-status Indians to the city. This idea would have horrified most Winnipeggers, who in the 1950s thought that all Aboriginal people should be rooted out of the city. The upheaval his proposal would cause to the Métis culture was never considered. Casual labour, traditional hunting and fishing, and seasonal work were all seen as inadequate means of obtaining a proper standard of living. So, despite some statements that gave lip service to protecting Métis culture, the conclusions and recommendations of the report worked to undermine it. In fact, one of Lagassé’s conclusions was that Métis culture and Canadian culture were incompatible. One wonders how he thought he could integrate an incompatible Métis Nation culture into Canadian culture without assimilation.

Lagassé had particular trouble defining the Métis. He simply could not come to grips with the complexities of such a people. He didn’t know where to start, and in the end he printed a list of things Canadians said about the Métis. He mixed up ideas of culture, class, race and self-identification. He used outside recognition as a way of defining the Métis. His definition also contained a buried concept that the Métis were a dwindling people destined for extinction. According to Lagassé, a Métis was a person with some Indian ancestry who could still be recognized as Métis because of their way of life, or to take it one step further, because of the way of life of their immediate blood relations.

The idea of integration was problematic in the implementation of the community development projects the study spawned. Remember, this was supposed to be the people helping themselves. The ideas from the Lagassé report filtered down into the Manitoba bureaucracy and influenced decision-making, particularly when Manitoba began the era of mega projects in its northern reaches. The failure to appreciate who the Métis were and the clumsy definition put forward by Lagassé would come back to haunt the Métis Nation in Manitoba for generations. It laid the foundation for their exclusion from consideration when Manitoba Hydro began the Churchill River Diversion, a project that decimated Métis communities such as Grand Rapids. The influx of new mining towns and the relocations and disruptions caused by the mega projects all ignored the Métis Nation as a collective entity.

It was a convenient position for the Manitoba government, and one that even in the twenty-first century has not changed. In 2018 the Manitoba government cancelled two multi-million-dollar agreements between Manitoba Hydro and the Manitoba Metis Federation. The agreements were an attempt by Manitoba Hydro to establish a new relationship with the Métis. When the premier cancelled the first agreement, calling it “persuasion money,” nine out of ten of the Hydro board directors resigned. When the second agreement was cancelled, the president of the Manitoba Metis Federation, David Chartrand, harkened back to the bitter history between the province and the Métis Nation. He said, “Why in the hell would you make that decision? What guided you? Is it vindictiveness? Do you want to get revenge on the Métis people because they stood up against you?”14 Plus ça change.