REORGANIZING THE MÉTIS NATION

In the 1960s the Métis Nation reorganized in the Prairies. The catalyst for the reorganization was the same threat the Métis had always faced: displacement. But this time the Métis were not being displaced because of settlement. For most Métis, especially in the northern parts of the provinces, the reorganization began in response to natural resources development—oil and gas in Alberta, uranium mining in Saskatchewan and hydro in Manitoba.

New leaders took over the reins. Stan Daniels was the Métis Association of Alberta’s president. Howard Adams, Rod Bishop and Jim Sinclair were working in Saskatchewan, and when the Manitoba Metis Federation officially organized in 1967, its new president was Adam Cuthand.

By the 1970s the search was on for something more than provincial organizations. The three Prairie Métis organizations formed the Native Council of Canada. Within a few years they invited the non-status Indians and Métis from other provinces into the organization. Thus began a period when the Métis Nation was represented by a pan-Indigenous organization. The Native Council of Canada lobbied the government and at the same time became delivery agents for government programs and services to Métis and non-status Indians.

After 1973, when the courts began to recognize the legal existence of Indigenous title and land rights, the federal government was forced to deal with the land claims of First Nations.1 But Canada refused to extend this recognition to the Métis Nation, claiming it had fully extinguished all Métis land rights. As far as Ottawa was concerned, that satisfied any obligations it may have had to the Métis as individuals. It had never recognized the Métis Nation. Case closed.

The Native Council of Canada and the provincial organizations began to have annual assemblies as well as local and regional meetings. Métis scholars began to research their history and the law. They started to tell the old stories to the assemblies, and this new generation of Métis became better educated about the law and Indigenous rights. The Métis Nation’s history formed the basis for a developing legal theory of Métis rights. Métis nationalism, a theme that had never been far from the surface in the Prairies, once again resonated loudly. But that national pride clashed with the aspirations of non-status Indians. The two groups, the Métis and non-status Indians, may have shared an organization but they shared little else. Their histories and trajectories were entirely different. Non-status Indians invariably tied their identity and culture to the First Nations they were connected to. The Native Council of Canada, the only national voice for the Métis, was thus compromised in its goals and aspirations. In 1977 Saskatchewan and Manitoba withdrew.

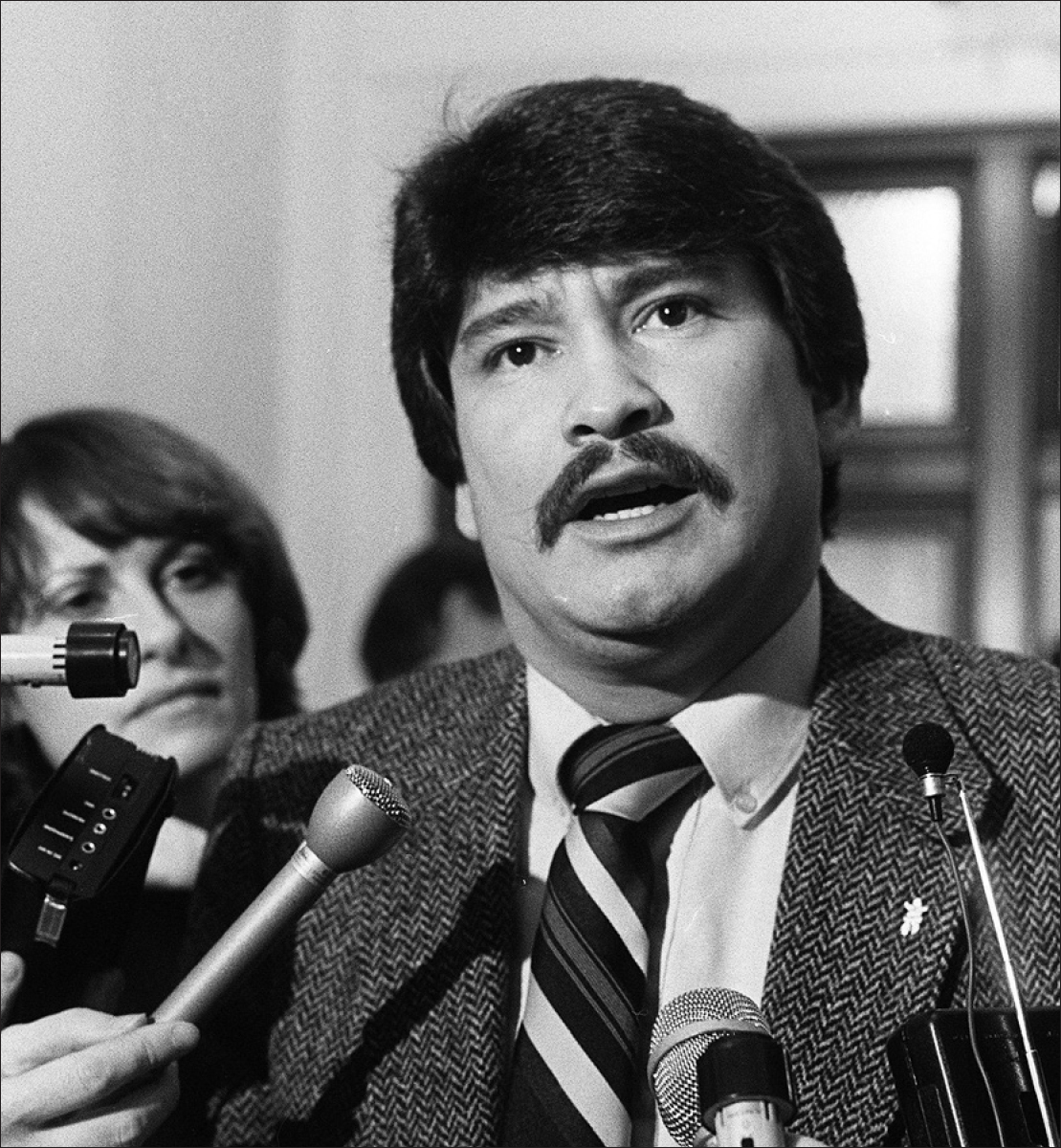

HARRY DANIELS

In the late 1960s Canada began three decades of constitutional debates. The 1960s also saw the rise of another dynamic Métis Nation leader: Harry Daniels. Harry was handsome and dapper, a dancer, an actor, smart and politically savvy. He was an inspiring speaker, passionate about Métis rights, and he was a scrappy fighter. He became the first voice of the Métis Nation in the constitutional debates.

Harry Daniels, 1998 (The Canadian Press/Fred Chartrand)

Riel had absorbed the ideas of Papineau and the thinking behind the American and French revolutions. Colonial theory, the labour movement and socialism inspired Norris and Brady. Daniels absorbed the revolutionary ideas and zeal of the American civil rights movement, the Black Panthers, the American Indian Movement, Frantz Fanon’s writings from Africa, and the human rights revolution that was sweeping the world. It was a powerful mix.

Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s move to patriate the Constitution became the target for Daniels. Trudeau was greatly attached to his “two founding nations” idea, the theory that Canada was founded by the English and French nations. Daniels attacked the idea. There were not two founding nations. In fact the Métis Nation was a politically independent nation when it joined Canada. The Manitoba Act was a contract of Confederation, a promise. Canada had broken that contract and turned the Manitoba Act into an empty broken promise.

Daniels argued that the Métis Nation’s identity was “suppressed and denied by the federal government in Ottawa, which looked only to England and France for its notions of culture.”2 When “multiculturalism” became the new buzzword, Daniels wanted Canada to know that Riel was the father of this idea. Multiculturalism? Bah! That was just repackaging the “two founding nations myth with some Ukrainian Easter eggs, Italian grapes and Métis bannock for extra flavour.”3

Daniels saw the constitutional debates as an opportunity to gain recognition for the Métis Nation with a distinct status within Confederation. He wanted participation and feared the Métis Nation’s voice and rights would be drowned out in the fierce federal-provincial horse-trading. When his fears proved true, Daniels staged an eight-hour sit-in in the House of Commons. He maintained that the sit-in was just a continuation of the meeting, albeit without the justice minister and other federal committee members. The point was to force the issue of the participatory status of the Native Council of Canada and through them, the participation of the Métis Nation. As Daniels put it, “We represent a whole nation of people who have been alienated. We have been trying for more than a century to get into Confederation.” The Métis Nation wanted what they had always wanted: they wanted in, but on their own terms.

On January 30 Justice Minister Jean Chrétien confirmed that the clause “The aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed” would be included in the Constitution. This was not nearly enough for Daniels. He demanded specific reference to the Métis in the clause. Chrétien tried to foist Daniels off with an assurance that the phrase “aboriginal peoples” would be generously interpreted. Daniels was often charming and he had a great sense of humour, but he could be Métis blunt too. With Chrétien he was . . . well, let’s put it this way: he wasn’t exactly polite. No deal, is what he said. No deal unless the Métis are specifically recognized. Daniels lobbied everyone. Committee members were harangued in hallways and corridors. And they listened. The deal was disintegrating under Chrétien’s fingers. With minutes to go before the cameras rolled, Chrétien announced an amendment to the Aboriginal rights clause, a new sub-clause. The new drafting was “The aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed. In this Act, ‘aboriginal peoples of Canada’ includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.”

The wording did not specifically reference the Métis Nation, but the provision uses the word “peoples” three times. The new constitutional protection was not designed to protect individual Aboriginal rights. It was designed to give protection to the rights of Aboriginal collectives. Daniels’s insistence on the specific inclusion of the Métis peoples of Canada left the door open for other Métis peoples to claim constitutional protection if they could prove they were ever a people. He never had any doubt the Métis Nation would meet this standard.

There was a significant group of Métis lawyers and advisers around Daniels, and they all deserve credit for their work. But in the end it was Harry Daniels’s tenacity that got the Métis included in the Constitution Act, 1982. Louis Riel put the Métis into the Canadian Constitution with their inclusion in the Manitoba Act, 1870. Harry Daniels got the Métis included in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

Was Daniels right to put so much pressure on the federal government and insist that the Constitution of Canada specifically recognize the Métis Nation as “one of the aboriginal peoples of Canada”? Today the Métis Nation celebrates him for what he accomplished in 1981. But in 1982 it was not clear that Daniel’s achievement could be considered a victory.

The Manitoba Metis Federation was particularly concerned. They had been preparing to launch a lawsuit that took aim at the failure to properly implement the Métis treaty that Riel had negotiated in sections 31 and 32 of the Manitoba Act, 1870. The president of the Manitoba Metis Federation, John Morrisseau, wanted to focus on the first Métis constitutional provisions that had not been fulfilled. He worried that the absence of Aboriginal consent on an amendment clause would permit the removal of sections 31 and 32 of the Manitoba Act, 1870. The Manitoba and Saskatchewan Métis organizations forced Daniels to make the Native Council of Canada’s support for patriation of the Constitution conditional on Aboriginal consent for constitutional amendments.4

Canada felt stung by the now conditional Métis support. Then on April 15, 1981, the Manitoba Metis Federation launched its lawsuit. On April 24, 1981, in perhaps the fastest government response the Métis Nation has ever experienced, Justice Minister Jean Chrétien sent a letter categorically rejecting the idea that Canada had any outstanding obligations with respect to Métis land claims.

Why put your efforts into a new constitutional clause when Canada would not fulfill its obligations under its first constitutional promise? There was little reason to expect things would change. To the Métis Nation it appeared that individual rights would be guaranteed, but their collective rights would not. Daniels had been the bold face of Métis support for patriation of the Constitution and the new Aboriginal rights clause. With the Chrétien rejection of Métis rights from the first Constitution and mounting disapproval from the Métis Nation, Daniels stepped down as president of the Native Council of Canada.

In September 1981 the Supreme Court of Canada forced Prime Minister Trudeau to abandon his plan for unilateral federal patriation, and with this judgment, the provinces gained considerable bargaining leverage. The Western premiers didn’t like the Aboriginal rights clause. They didn’t much like the Charter either, and in the horse-trading that ensued, the Aboriginal rights clause was sacrificed for Charter support. The provinces were afraid of the broad nature of the clause.

In the summer of 1980 the Native Council of Canada had established its own Constitutional Review Commission. It was Daniels’s way of involving Aboriginal people in the constitutional discussions. Daniels was the commissioner. The deputy commissioners were Margaret Joe (Commodore), Rheal Boudrias, Duke Redbird, Viola Robinson and Elmer Ghostkeeper.5 The commission went on the road and held meetings across Canada. It got an earful from the Métis in Manitoba about the constitutional promises already made and broken. Daniels wouldn’t even call a meeting in Saskatchewan. In July 1981 Daniels stepped down, and Jim Sinclair became the commissioner of the Constitutional Review Commission.

DIVORCE

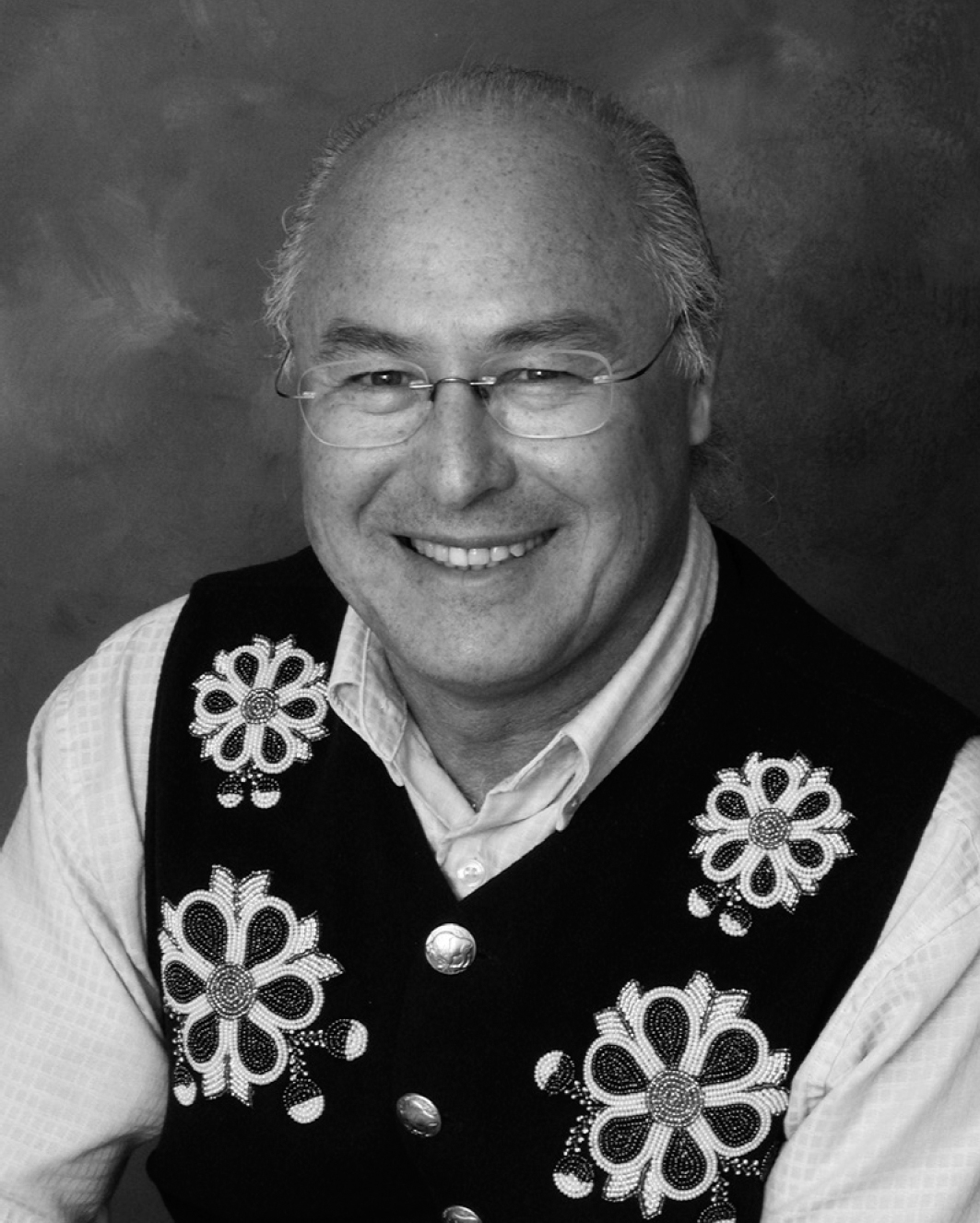

It became the task of Elmer Ghostkeeper and Jim Sinclair to pick up where Daniels had left off. Ghostkeeper was the president of the Alberta Federation of Métis Settlements. Under his leadership the Alberta Métis settlements were regaining their own voice. Manitoba might be fighting for fulfilment of the promises made in the Manitoba Act, but the settlements had land and they had a form of self-government. They were already in court against Alberta to stop the province from taking their resource money and further encroaching on their self-government powers. Ghostkeeper was maintaining the lawsuit, was encouraging the settlements to flex their jurisdictional muscle and was also on the Constitutional Review Commission. He wanted constitutional protection for Métis settlement lands. Alberta had shut down some settlements already, and Ghostkeeper wanted to make sure that would never happen again.

Elmer Ghostkeeper, 1981 (The Canadian Press/Gordon Karam)

Would the Aboriginal rights clause protect the Alberta Métis settlement lands? Ghostkeeper thought so and he wanted the clause back in. He joined a crowd of five thousand protesters in Edmonton to put pressure on Premier Peter Lougheed to put the clause back into the Constitution. But it was not Ghostkeeper and the settlements who broke the provincial deadlock on the Aboriginal protection clause. When Clément Chartier, a Métis lawyer, explained that Indigenous rights were not new rights and that they already existed, Premier Lougheed latched on to the idea and proposed inserting the word “existing” into the clause, thereby ensuring that the rights protected were those that existed as of the effective date of the patriated Constitution. The provinces accepted the proposal and Parliament adopted it in December 1981. Defining the existing rights was deferred to the First Ministers’ conferences that were to follow.

The new Constitution recognized three distinct Aboriginal peoples in Canada—Indians, Inuit and Métis. But non-status Indians were not a distinct group. They were individuals from First Nations all across the country whose only common issue was that they had lost their status under the Indian Act. They had serious legal issues but not constitutional ones, and the upcoming constitutional conferences were specifically about constitutional rights.

By 1982 the Native Council of Canada’s president and vice-president were both non-status Indians. The Métis Nation had initially created the organization, but it was now fully captured by non-status Indians who wanted to press on their issues, not Métis Nation issues. Who then would represent the Métis Nation at the upcoming constitutional conference to determine the content of Métis Nation rights in the new Constitution?

The issue of representation at the 1983 First Ministers’ conference collided with the issue of Métis Nation representation on its only national organization. Ghostkeeper wanted a Métis national voice, which would never be achieved, he was convinced, if the Métis Nation stayed under the umbrella of the Native Council of Canada. A committed group of Métis nationalists began to gather, inspired by Ghostkeeper. A divorce was in the making.

There would be two available seats at the table for the Native Council of Canada during the conferences. Since First Nations were already well represented with two seats, Sinclair wanted the two Native Council of Canada seats for the Métis Nation. The Native Council of Canada vehemently disagreed. The Métis walked out. Actually, describing their exit as “walking” is a bit of an understatement. They were angry and defiant. Sinclair resigned as commissioner of the Constitutional Review Commission. The marriage of convenience between the Métis Nation and non-status Indians was over. It was January 14, 1983.

CREATING THE MÉTIS NATIONAL COUNCIL

On January 22, 1983, over one hundred Métis from all over the Métis Nation met in Edmonton to form their own national organization. Representatives came from northwest Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, the Métis settlements and northeast British Columbia. The meeting established a Métis Constitutional Council to participate in the constitutional conference. The members were the three Prairie provincial organizations and the Federation of Métis Settlements.6 Ghostkeeper opened the meeting by quoting Louis Riel, who had said that the Métis Nation would rise again a century after his death. It was almost exactly a century since Canada hanged Riel in 1885. The symbolism struck a chord with everyone there.

The First Ministers’ conference was scheduled for March 15 and 16, 1983. Everything about the conference pointed to the exclusion of the Métis Nation. But the conference was crucial. All the other Indigenous peoples had processes to deal with the government, plus the conference. The Métis Nation had no processes and everyone denied they had rights. They only had one chance and it was the First Ministers’ conference. But they had no seat at the table.

Ghostkeeper put the Métis Nation case forward at a meeting with federal and provincial government representatives. He referred again to Louis Riel and reminded them that Riel had been denied his seat in Parliament. Ghostkeeper accused the chair of repeating history. He blasted Canada for excluding them from the conference. Then the Métis walked out. They wrote a letter to Trudeau informing him that they were forming their own national organization and that they wanted two seats at the table. And then they went to court.

On March 8, 1983, members of the boards of the Prairie Métis organizations established a new national governing body, the Métis National Council. There were immediate casualties in the establishment of the Métis National Council, and Elmer Ghostkeeper was one of them. The Métis Association of Alberta agreed to come on board, but only if it was the sole organization representing the Métis in Alberta. The decision to run the Métis National Council as a federation of provincial organizations left the Federation of Métis Settlements, the body that represented the only Métis with a land base, out of the national body. The Métis settlements would have to be represented by the Métis Association of Alberta, the province-wide body, or not be part of the Métis National Council at all. The Métis settlements opted to stay out, and to this day this particular political rift within the Métis Nation has not been healed.

Clément Chartier was elected to represent the Métis Nation at the upcoming First Ministers’ conference. The Métis National Council filed an injunction to stop the conference unless they were invited to the table. The judge urged the parties to try settlement discussions. But the lawyers were getting nowhere. Then, just minutes before they were to reconvene court in the afternoon, Chartier got word that Canada had agreed to their demand for separate representation.

Clément Chartier, president of the Métis National Council, circa 2017 (Métis National Council)

The offer from Canada was contingent on the Métis National Council dropping its lawsuit. Chartier was also promised that a Métis Nation land base could be inserted into the agenda. The catch was that Canada only offered one seat. It wasn’t fair, and Sinclair and Chartier were not happy about the inequity, but they accepted. Everyone held press conferences. The Métis claimed victory. The Native Council of Canada cried foul and railed against the heresy of Métis nationalist claims. All this took place just five days before the First Ministers’ conference began.

CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCES OF THE 1980S

With hindsight it is easy to see how overblown expectations were for the conferences. The first conference was a two-day affair. Defining the content of Aboriginal rights could never be accomplished in two days—but that’s 20/20 hindsight. At the time there was hope. Chartier and Sinclair spoke passionately about the history of the Métis Nation and their desire for a land base and self-government—a place, as Chartier put it, that the Métis Nation could call its own. Sinclair argued for the need for constitutional protection to keep Métis Nation rights out of the reach of the political winds of fortune. The reason the Métis Nation was still fighting a hundred years after Riel was because the Canadian democracy had failed them. This was an opportunity to change that history, to walk down a better road. Some amendments were made to the Aboriginal protection clause, but there was no progress on rights definition in the 1983 First Ministers’ conference or in the 1984 conference.

The 1985 conference involved different players. Brian Mulroney’s Conservatives were in power in Ottawa, and there was only one topic: self-government. Canada’s approach required the provinces to commit to the negotiation of self-government. British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan were not prepared to make such a constitutional commitment, and the agreement was watered down to a non-binding political accord. The Métis National Council reluctantly agreed, but the First Nations and Inuit would not agree. Thus ended the third First Ministers’ conference.

The final round was in 1987. Self-government dominated the conference as it had in 1985. The three Western provinces reiterated their previous position. They would not agree to a commitment to negotiate self-government. British Columbia stepped back even further when it said there was no room in the Constitution for Aboriginal self-government. None of the Western provinces wanted to enshrine an undefined inherent Aboriginal right to self-government in the Constitution.

Jim Sinclair, 1987 (The Canadian Press/Chuck Mitchell)

Jim Sinclair had the last word. He used it to blast the premiers. He started with British Columbia’s premier, an immigrant who claimed the right to refuse to even negotiate self-government rights with the original inhabitants. Quebec was next for not coming to the aid of the Métis Nation. He saved most of his wrath for Saskatchewan. This was a province that subsidized alcohol so it was the same price in the north as in Regina, but would not give a subsidy for milk for children. This was a province that had recently given a blank cheque and land to an American pulp and paper company—more land than all the reserves in Canada—and this it did with an open-ended agreement. No definitions were asked of them. Sinclair went on to say:

We have struggled hard to make a deal. We have kept our end of the bargain . . . One thing I want to say, as we leave this meeting: I am glad that we stuck together on a right that is truly right for our people, right for all of Canada, and right within international law throughout the world . . . We have the right to self-government, to self-determination and land . . . This is not an end. It is only the beginning . . . Do not worry, Mr. Prime Minister and Premiers of the provinces . . . our people will be back.7

When he was done all the Aboriginal people in attendance burst into applause. And it was all done on live TV. The First Ministers’ Conferences were a failure from the Métis Nation’s perspective, but it had gained its national voice in the Métis National Council.

NO PARDON FOR RIEL

The next round of constitutional negotiations headed down the same road the First Ministers’ Conferences had already walked. When the Meech Lake Accord was up for ratification, the question was whether the offer of “distinct society” status for Quebec provided an opening for the Métis Nation. Yvon Dumont, president of the Manitoba Metis Federation, in defiance of all the other Indigenous organizations, thought there was a possibility for the Métis Nation to also be recognized as a distinct society. He was the only Indigenous leader to support the Meech Lake Accord. Ultimately it didn’t matter. The Meech Lake Accord was doomed, and Canadian attention was galvanized by two events: the Oka crisis in the summer of 1990, and the threat of a Quebec sovereignty referendum in 1992.

As unlikely as it seems, these two issues brought Louis Riel back into Canadian consciousness. What did Riel have to do with a Mohawk uprising at Oka and the Quebec sovereignty referendum? It seems an unlikely triad, but it can be explained by the historical relationship between the federal government and Indigenous peoples, and the historical relationship between Quebec and the rest of Canada.

For centuries Canada has denied, stalled or stifled the legitimate rights and grievances of Indigenous peoples. There is a predictable cycle of peaceful protest and government denial that eventually erupts in violence. Names like Batoche, Ipperwash and Oka each contain a story of Indigenous resistance.

Oka became a household word when the Mohawks set up barricades to prevent the expansion of a golf course onto their ancestral lands. Most of the press ignored the real issue: Canada’s failure to resolve Mohawk land claims. After decades of peaceful agitation by the Mohawks to stop the continual erosion of their lands, Canada still refused to even consider negotiation or a peaceful resolution to the issue. In closing off legitimate avenues of resolution, the federal government created the perfect setting for the eruption in the summer of 1990.

Only after Oka did the government begin to address the long-outstanding land issues of the Mohawks. In response to the events at Oka, the government did what we have seen many times in this history—they set up a royal commission. This one was called the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

In 1987 Canada’s first ministers negotiated the Meech Lake Accord. The process of the Meech Lake Accord negotiations fuelled the anger and resistance of Indigenous peoples because the issue of their rights had not been addressed. Because the Meech Lake Accord would have recognized Quebec as a distinct society, its defeat fuelled the anger and resistance of Quebec. Quebec felt rejected by English Canada, and the creation of the Bloc Québécois—a party devoted to Quebec nationalism and separatism—was one of the results.

Ottawa was being pressured on all sides to respond to the two outstanding and troubling issues of Canadian unity, Quebec and Indigenous peoples. The narrow defeat of the Quebec referendum on sovereignty in 1995 shook the government’s complacency about the enduring commitment of Canadians to maintaining Canada. The violence that was building in Indigenous communities also needed to be addressed.

Finally, in January 1998 the government released its response to the report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. The response was in the form of a new government policy, Gathering Strength. The policy was described as an “action plan designed to renew the relationship with Aboriginal peoples of Canada.” The policy stated that the commission’s report had acted as a catalyst and an inspiration for the federal government’s decision to set a new course in its policies for Indigenous peoples. But when the draft policy was shared with Indigenous leaders prior to its announcement, there was nothing in it for the Métis Nation.

Métis Nation leaders were outraged that there was no new course in Canada’s policies or any meaningful action plan for the Métis Nation. Virtually overnight, Canada redrafted a statement of reconciliation. All Métis Nation issues that required reconciliation were reduced to the issue of a pardon for Riel. It was preposterous. In 1992 the Manitoba Legislative Assembly had already passed a unanimous resolution to honour the role of Louis Riel in the founding of Manitoba. That same year, the House of Commons and the Senate passed unanimous resolutions to recognize and honour the role of Louis Riel: “[T]hat this House recognize the unique and historic role of Louis Riel as a founder of Manitoba and his contribution in the development of Confederation; and that this House support by its actions the true attainment, both in principle and practice, of the constitutional rights of the Métis people.”8 With all the wrongs that needed to be dealt with, it was outrageous for Canada to suggest that once again affirming the contributions of the Métis and reflecting Riel’s place in history would even begin to address the issues. Métis Nation leaders could hear Riel turning over in his grave.

It was in this dynamic context, where the issues of Quebec and Indigenous peoples were so intertwined, that the movement to exonerate Riel was reinvigorated. It is no surprise that Quebec influenced the exoneration movement. Quebec has always played a role in the Riel debate. After the initial uprising began in 1885, the French-language press in Quebec slowly came to the support of the Métis Nation. When Riel’s death sentence was pronounced, support in Quebec turned to outrage. After the hanging in November 1885, the relationship between francophones and anglophones in Canada was forever changed. French Canadians believed Riel died because he was French and Catholic; they saw the loss of Riel as the loss of French access to the West. In the immediate aftermath of Riel’s death, the Conservative government in Quebec, seen as Protestant and English, was roundly defeated. The new Quebec government was nationalistic and devoted to Quebec autonomy. In this way, the hanging of Louis Riel fertilized the nascent movement we call Quebec separatism.

Quebec has never let go of its attachment to Riel, and Quebec nationalism continues to play a role in the Riel exoneration dialogue. To that end, private member’s bills to exonerate Riel have been sponsored by members of the Bloc Québécois, and the motivating force behind the Bloc-sponsored bills is exoneration of a francophone leader, not a Métis leader. If Riel were to be exonerated, it would set a precedent that would make it harder to accuse Quebec’s separatist leaders of treason. In 1996 and again in 1997, Riel exoneration bills were introduced into Parliament. The debate in the House of Commons tied together the issues of reconciliation for Quebecers and francophones, and exoneration of Riel. On October 21, 1996, Jean-Paul Marchand, a Bloc Québécois member, spoke during the second reading of An Act to Revoke the Conviction of Riel:

Louis Riel was led before a jury of six Anglophones and tried by an anglophone judge in Regina . . . In that same year, French was banned in Manitoba. Louis Riel was, in fact, the victim of a miscarriage of justice that reflected the attitude to francophones at the time. People in Quebec knew that Louis Riel’s cause was just . . . and Quebecers and francophones across the country were outraged by the decision made by a jury of six anglophones, negating the rights of Louis Riel. Despite the uproar this caused in Quebec, even John A. Macdonald, the Prime Minister of Canada at the time, said: “All the dogs in Quebec can bark, but Louis Riel shall hang.” John A. Macdonald said that. It was a way to punish the French fact in the west, although the rights of francophones were supposedly guaranteed. I may also point out to my dear colleagues from western Canada that subsequently the rights of francophones in Manitoba were abolished for one hundred years.

The conviction of Louis Riel was unjust, unacceptable and unpardonable. If people want to reconcile Canada with its francophones, let them adopt, fairly and squarely, a formula to absolve or pardon Louis Riel.9

The Riel exoneration movement is part and parcel of the fabric of Canada.10 Exoneration for a francophone leader is intimately connected with the place of francophones and Quebec within our society. For many Quebec proponents, exoneration has little to do with the man—Riel—and even less to do with his people—the Métis Nation.

Whether called exoneration or a pardon, such an act is one of extrajudicial clemency. It is a government grant of political expediency. It is never about justice or mercy. Clemency is never a statement of the accused’s innocence and always implies guilt and forgiveness. The government would be exonerating itself, not Riel. That is why the Métis Nation has rejected all calls for a pardon or exoneration. In their opinion it was Canada that committed the crime of hanging Riel. It would be more logical for the Métis Nation to pardon Canada. As one of the Métis Nation’s legal scholars, Paul Chartrand, put it, “the hanging of Louis Riel is a stain on the honour of Canada. Let the stain remain.”11

A NEW MÉTIS NATION TREATY—THE MÉTIS NATION ACCORD

Over a decade of Métis Nation constitutional negotiations culminated in May 1992 with the Métis Nation Accord. In the Charlottetown round, there was no confusion about who negotiated for the Métis Nation. The main issue for them was the jurisdictional question. Under the Canadian division of powers, “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” was a jurisdiction allocated to the federal government. For the purposes of this provision, s. 91 (24), the term “Indians” is a purely legal term. It is not a cultural identification. First Nations and Inuit, vastly different Indigenous cultures, were known to be included. But the Métis Nation was ignored, which was a problem because it allowed the jurisdictional hot potato to continue to be juggled between the provinces and the federal government. It always left the Métis Nation with nothing and no one to talk to in government. Yvon Dumont, the president of the Métis National Council, staged a filibuster in Edmonton to press on this issue.

Constitutional provisions are supposed to be given a large and liberal interpretation, which would logically mean that all Indigenous people were included in the clause that gave jurisdiction to the federal government. But logic was not what guided the federal government’s refusal to include the Métis Nation. It was money. They were afraid that the provinces, which currently covered Métis programs and services, would off-load them onto the federal government. First Nations didn’t want Métis in “their” provision. They worried that the financial pie, already sliced too thin, would be cut into many more pieces.

These positions infuriated the Métis Nation. It was a question of constitutional law, not a financial decision. Opening up federal jurisdiction to include the Métis Nation didn’t have to mean First Nations would get less. After much negotiation, the Métis Nation secured an agreement to amend federal jurisdiction to include the Métis and a further agreement not to reduce services. Negotiations would begin for a Métis land base, and governments would fund and participate in an enumeration and registration of the Métis.

With those important agreements under their belt, the Métis proceeded to draft the treaty they named the Métis Nation Accord. When the Métis Nation draft treaty was put on the table, the First Ministers agreed to the content. They balked at making it a constitutionally protected treaty, but they did agree to make it legally binding. Constitutional protection would have been better, but the Métis Nation Accord stood as the gold star agreement for the Métis.

It was a politically negotiated agreement that gave the Métis Nation the foundation they sought. There was recognition of the Métis Nation, a definition of Métis Nation citizens, a commitment to resources for an enumeration, the development of a registry, negotiations for lands and resources, an agreement by the provinces to provide lands, devolution of programs and services, self-government negotiations, an amendment to s. 91 (24) to include Métis, and funding for Métis institutions. The Métis settlements in Alberta would be protected and the Métis Nation Accord would be binding on the provinces and the federal government. All parties—the Métis Nation, the federal government and the provinces—agreed to the Métis Nation Accord.

It was a remarkable achievement and if it had been implemented, the course of Métis Nation–government relations would have changed forever. Unfortunately, the Canadian public voted the Charlottetown Accord down in a referendum and the Métis Nation Accord went down with it.