One more step was necessary for the development of a new nation. The northmen had to go free. “Going free” meant disengaging from their employers, their attachments in eastern Canada and from the tribes.

The merger of the two fur-trade companies in 1821 led to more than a thousand men losing their jobs. Many of these men went free and stayed in the North-West. They stayed because they had married Indigenous women. These “Freemen” began to move to Red River from the Great Lakes, Athabasca, Fort Edmonton, the Saskatchewan, York Factory and the Pacific slopes of the Rockies.1 Between 1831 and 1840 the population of Red River almost doubled. In 1832 it was 2,417 and in 1840 it was 4,369.

Once free from his contract with a company, a Freeman became an independent hunter-trader. Travelling in groups of two or three with their families, the Freemen hunted buffalo and other large animals for their food. In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, they began to roam throughout the North-West. If the product of their hunts did not provide enough for their families, they did odd jobs, freighting or voyageur work for the trading companies. But their preference more and more was to hunt buffalo.

The Freemen found a niche as suppliers and traders providing the posts and the brigades with buffalo meat, fish, baked bread, salt, and maple or birch syrup. They operated taverns and restaurants on trade routes and provided the voyageurs with the means to repair canoes. They also played the role of middlemen. Obtaining goods from Canadian posts, they would trade with Indians for furs and sell the furs back to the Canadian traders, making a bit of profit along the way. Some had visions of their own grandeur. One old Freeman claimed a sturgeon fishery for himself with the title “King of the Lake.” Another Freeman called himself “Lord of Lake Winnipick.” Yet another proclaimed himself a “sovereign.”

Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière was one of the Freemen. When he and Marie-Anne arrived in Pembina, his partners reunited with their Cree wives, and this small party of Freemen with their families went out onto the Plains to hunt buffalo. Pembina is where the first two non-Indigenous children in the North-West were born. Both were born the same week in 1807. One child was born to Isobel Gunn, a young woman who had been masquerading as a man and was forced to reveal her gender only when she went into labour. The second child was Reine, a daughter born to Marie-Anne and Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière. By 1810 the Lagimodières had three children. Their third child, Josephte, was nicknamed La Cyprès after the Cypress Hills where she was born.

The 1790s was when the northmen began to move onto the Plains and hunt buffalo on horseback. It was the beginning of the transformation of the voyageurs into Plains buffalo hunters. At first they lived on the edges of the Plains, in places such as Pembina. In 1805 Alexander Henry’s census listed 176 Freemen and their families in what is now southern Manitoba.2 The first rough Freemen settlements began to appear around 1801, first at Pembina and farther up the Red River at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. At Rainy Lake a small village was established in 1817. Fort Edmonton, Île-à-la-Crosse, Cumberland House and other regional forts became home bases for Freemen with their families. By 1814 the Freemen and their families moving throughout the Red River region numbered about two hundred. At Pembina there was a similar-size group.

The Freemen first adopted and then adapted the Plains tribal horse culture. Previously, as voyageurs, they were bound to their canoes and dogsleds. After going free they took up the horse. For thousands of years the Plains tribes followed the buffalo on foot. The arrival of the horse in the northern Plains in the 1600s did not create a new Plains Indigenous culture. It didn’t change the range of territory the people covered, their pursuit of the buffalo herds or their practice of congregating in small bands of a few families. What it did was allow the people to carry more. The Freemen added another adaptation to the carrying capacity of the horse: their new invention, the Red River cart.

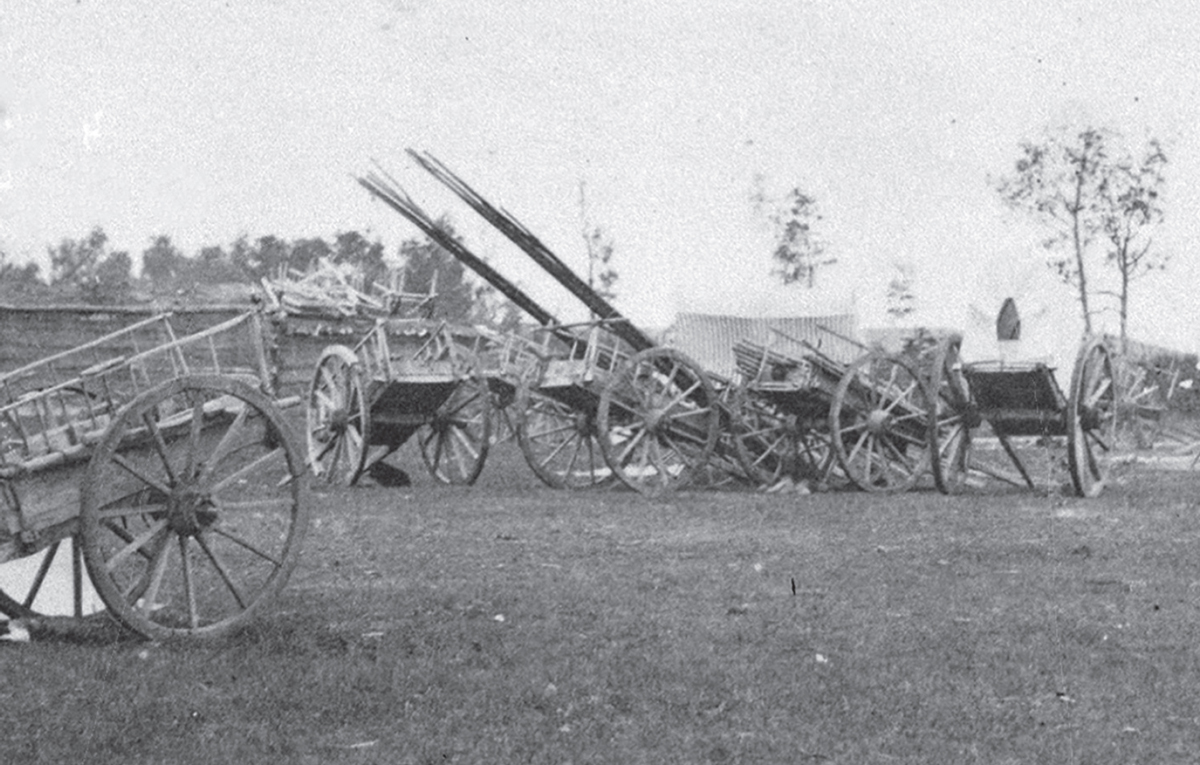

Red River carts were made entirely of wood with strips of leather (babiche) wrapped around the wooden wheels. Horses or oxen pulled the carts. If pulled by a horse, they carried less but could travel farther. A cart could become a boat by detaching the wheels and floating it over a river.

On land the carts were loud—very loud. They emitted a high-pitched shriek that could be heard several miles away. The sound came from wooden wheels grinding on wooden axles. No axle grease was used because it served only to collect the dust of the Prairies, which clogged up the wheels. The carts were so identified with the Métis that the Sioux sign language gesture for the Métis was the sign for a man followed by the sign for a cart.

Red River carts with teepee poles (Library and Archives Canada C-087158)

The Freemen also adapted the hunting partnership custom from the boreal forest and Plains tribes. These partnerships formed when several men combined families and labour to exploit a particular winter hunting ground. The families in the partnership depended on each other. There was more security in numbers than could be achieved by a single family travelling and hunting on its own. The adaptation of the Plains Freemen was to take the partnership idea and move it to a much larger territory and to a larger group of hunters.

One of the central tenets of the partnership custom was sharing, which quickly became part of the developing Métis Nation ethic. Sharing was spontaneous and unstructured. It was in no way changed by the fact that part of the hunters’ catch was destined for the commercial market. The production of buffalo meat for market was important to the Freemen hunters, but it was subordinate to their subsistence requirements. Sharing was not charity. Because starvation was a constant visitor, no one hesitated to turn to others for help. Not only would help always be forthcoming, the giver felt the obligation deeply and would be ashamed of himself if he did not provide it. One hunter, after having given the last of his flour and lard to two men from a neighbouring band—food he likely needed himself—said, “Suppose now, not give them flour, lard—just dead inside.”3

The Freemen made one other adaptation to facilitate their movement to the Plains. They adopted the Plains tribes’ staple diet: pemmican. Robert Kennicott, an American naturalist and herpetologist, was less than enthused about it: “Pemmican is supposed by the benighted world outside to consist only of pounded meat and grease; an egregious error; for, from experience on the subject, I am authorized to state that hair, sticks, bark, spruce leaves, stones, sand, etc., enter into its composition, often quite largely.”4 It was pemmican that allowed the Freemen to be independent, to live separately from the tribes, the traders and the fur-trade posts.

The Hudson’s Bay Company thought the Freemen a great nuisance, dishonest scoundrels and a threat that took away business. But the Freemen had tasted a new and different life based on an egalitarian theory of opportunity with no company boss. More and more Freemen took their families to the Plains.

It was the emotional commitment to independence and freedom that led the children of the Freemen to the acquisition of a national consciousness. They were “bred and brought up in the very hotbed of liberty & equality.”5 Being free was an identity that would embed itself deeply in the Métis Nation, whether they were buffalo hunters, farmers, hunter-trappers or voyageurs. Their attachment to liberty was inherited, at least in part, from their Indigenous mothers, a fact that the English only understood after a hundred years on the continent, when they admitted, “We know them now to . . . have the highest notions of Liberty of any people on Earth.”6 But their deep attachment to freedom also came from their voyageur fathers, the northmen who went free.

The British were far away across the sea, and Canada was on the other side of the Great Lakes. In the North-West there was no call of loyalty to country. There was no monarchy, no one to represent the law, no government and no authorities. There was only the Hudson’s Bay Company, and its power was limited to the small areas around its few forts.

The Nor’Westers and the Company men may have thought they were in charge of the North-West, but it was a hollow claim, much like the preposterous claims of Radisson and Des Groseilliers, who arrived at the end of Lake Superior in 1659 to 1660 and proclaimed themselves “Caesars” who had taken the First Nations under their protection. According to their own marketing, which was aimed at their European audiences, they were able to make thirty thousand Indigenous people scattered over a thousand miles comply with their wishes.7 Whatever else they were, Radisson and Des Groseilliers were brilliant self-promoters, and their propaganda set the tone for the Euro-Canadian attitude toward the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes and the North-West for centuries to come.

In reality the traders, until well into the second half of the nineteenth century, were insignificant in the face of the vast tribes, the growing body of Freemen families, and a newly developing people, the Métis Nation. Most of the people in the North-West spent the bulk of their lives far away from the Company forts and outside the sphere of Euro-Canadians’ purportedly overwhelming influence.

The Freemen formed their own families, their own partnerships and their own loyalties. They began to see the North-West as theirs. This established a sharp contrast between them and the Canadians or Europeans, who, as tourists, adventurers or traders in a foreign land, would eventually go home. The North-West became home for the Freemen and their young families. Going free changed the focus of their economic livelihood. According to the Hudson’s Bay Company and the American government, the Freemen were smugglers. They preferred to think of themselves as free traders.

This is the fertile soil into which the Métis Nation was born. The men had bonded initially as voyageurs. In that milieu they forged indelible relationships with roots in the companionship, hardship, songs and travels of the voyageur northmen. They formed alliances with Indigenous peoples, married Indigenous women and began to have families. Then they went free from the tribes. At first the separation from a wife’s band was seasonal. But as time went on, the Freemen families lived completely separate lives from the bands.

It was the generation born to the Freemen families in the 1790s that became a recognizable group when they hit their twenties. While the previous decades saw the birth of many such children, by the late 1700s their numbers in the North-West had reached a critical mass. These children were now marrying each other and beginning to create a new culture and language. In all parts of the North-West, this cohort began to attract recognition. When they reached maturity in the early 1800s, they were no longer identified as the sons and daughters of the northmen or Freemen. They did not identify as members of the tribes and they had never considered themselves to be connected to eastern Canada. They began to think, act and identify as a separate group. They gave themselves a collective name: the Bois-Brûlés.

They learned to live in and love the North-West as their motherland, and they were fiercely proud of their independence and freedom. There was no authority that could interfere with their developing network of families and nothing to dampen their aspirations. They were free to become anything they wanted. They chose to become a new nation.