THEY LIVE ENTIRELY BY THE CHASE

Buffalo meat was both food and currency. Wages were paid in buffalo meat, as was the price of land and payment to the missionaries for educating Brûlés children. While the Selkirk Settlers made valiant efforts to produce crops, there is no question that agriculture at Red River was mostly a failure until after 1870. In thirty of the years between 1813 and 1870, the crops were destroyed. Crop destruction came in many forms: grasshoppers, spring and fall frosts, fires, mice, disease, hail, floods and lack of or too much rain. The 1820s were a particularly bad decade. While the fisheries of Lake Manitoba and at Red River provided an important backstop, buffalo was the food everyone relied on, and the Brûlés buffalo hunters were the main providers of that food. They earned good money for their work, and this too was an incentive to remain on the Plains and follow the herds. Alexander Ross wrote, “[D]uring the years 1839, 40, and 41, the Company expended £5,000 on the purchase of plain provisions, of which the hunters got last year the sum of £1,200, being rather more money than all the agricultural class obtained for their produce in the same year.”1

Buffalo running through grass (Saskatoon Public Library LH-3065)

Some of the Freemen settled down to farm in Red River, but farming had little appeal for most Brûlés. Their Freemen fathers had not escaped farm life in Quebec, gone free and earned prestige as hunters and traders in order to trade all that in for farms in the North-West. For their sons, the monotonous toil of the settlers had virtually no appeal. They lived, as George Simpson said, “entirely by the chase.”2 They liked the freedom of the Plains, the wind in their faces and the constant change that mobility brought. They might like eating potatoes, but not enough to hang around and watch them grow.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, the Selkirk Settlers wintered at Pembina, and the Freemen and Brûlés hunters gathered there in order to hunt in the buffalo preserve at Turtle Mountain. Virtually everyone deserted the colony at Red River in the winter. They might stay in Red River over Christmas for celebrations, but they would quickly return to Pembina, the Plains or the fisheries on Lake Manitoba or Lake Winnipeg. Life was easier at Pembina. The weather was milder and it provided easier access to the buffalo.

In those early days the hunters went out in every season. Spring travel was difficult because the melting snow left the ground soggy, but there were summer, winter and fall hunts. By 1826 this irregularity had been replaced by two annual hunts, one in summer and one in winter. They would often hunt around Turtle Mountain, but other times they headed farther north around Brandon House. Freemen and Brûlés hunted both with and apart from the organized hunts. But if they travelled apart, it was in a group. It was always necessary to guard against attacks, particularly from the Sioux.

The growing numbers of Freemen and Brûlés congregating in Pembina made George Simpson, the governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company uneasy. They were too close to the American traders and their presence provoked the Sioux. Simpson moved the Company’s Pembina post some sixty miles north to the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. He pressed the small Pembina settlement to relocate north of the border. Many did just that. Some relocated to the land Cuthbert Grant had received from Simpson on the White Horse Plain. From Grantown the Brûlés continued to hunt buffalo under the leadership of Grant.

After 1816 the Freemen and Brûlés buffalo hunt began to grow in earnest. This is where the genius of Cuthbert Grant can be seen. It was Grant who set up the organization that would grow into the legendary Métis hunts. Grant brought the wild and independent Freemen and Brûlés together. He fostered an atmosphere where they maintained their pride and freedom and yet still learned to work together as a unit. And Grant devised the democratic rules—the command structure, the elections and the laws of the hunt. Rarely has a charismatic leader been so effective on the administrative and organizational front. Rarely has such a leader been able to transform enthusiasm and exuberance into an institution built on everything the Métis cherished—freedom, mobility, democracy, the family and the hunt. Grant forged this raw material, this ragtag lot, into a mobile, armed host.

In the 1820s the Freemen and Brûlés hunters on the great buffalo hunts came together from three locations: Pembina, the Forks and the White Horse Plain. The rendezvous was on the Pembina River, just south of the border. When all the families arrived at the rendezvous, an assembly was called. The chief captain of the hunt was elected, and in those early days it was often Cuthbert Grant. The chief captain of the hunt then chose ten dizaines (captains), “the old hunters,” who subsequently chose ten scouts and camp guards. The chief captain of the hunt and the ten captains became the Council of the Hunt.

The organization of the buffalo hunt with its captains, chain of command and laws of the hunt evolved into an efficient, effective and democratic Bois-Brûlés government. Orders from the Council of the Hunt were strictly obeyed and enforced. The Council assigned all duties. The first assignment, and one of the most important, was guard duty. This was a highly respected office and required men who were prepared to live in a state of constant vigilance for the duration of the hunt. Guarding the horses was one of their important jobs. The entire party relied on the horses. If they were stolen, lost or damaged, everyone would suffer.

The next task of the Council was to choose the hunters. These were men who were good shots and owned fast buffalo runners—horses trained to the chase. The hunters were tasked with choosing buffalo with good hides. They all wanted healthy, fatty animals, usually young cows.

The scouts were appointed next. They acted as sentries for the protection of the camp. Depending on where the hunt was taking place, the scouts always wanted to know where the various bands of First Nations were. If the Métis hunting camp was in Sioux territory or near Blackfoot territory, extra caution was needed.

Before departing on the hunt, the participants met in assembly to make all the decisions about the conduct of the hunt. At these assemblies they also considered other matters. In 1850 the assembly considered and voted on the representatives they hoped would be appointed to the Council of Assiniboia. They elected Narcisse Marion and Maximilien Dauphine to represent the Canadians, and François Bruneau, Pascal Breland and Salomon Hamelin to represent the Métis. The Council of the Hunt also dispensed justice for offences that occurred during the hunt. Their rules became known as the Laws of the Hunt.3 The decisions of the Council formed a body of laws that became known as the Laws of the Prairie.

THE NOISY MUSICAL RIDE

Moving from the rendezvous onto the Plains was slow and orderly, but not quiet. The people sang, talked, laughed, gossiped, quarrelled and joked as they travelled, all at full volume over the ear-splitting shrieks made by their Red River carts.

The buffalo contributed in their own way to the symphony of sounds on the hunt. A stampeding herd made the grass crackle like a fire, and this sound too could be felt and heard for a long way off. Add to this the barking of hundreds of dogs accompanying the moving camp. The final addition to this musical ride was the mosquitoes. Joseph Kinsey Howard penned a vivid description of them:

Wind-borne swarms of mosquitoes, often preceding thunderstorms, bore down upon the cart brigades in such numbers that horses, dogs and drivers were overwhelmed within a few seconds. While the horses pitched and screamed under the attack of the savage insects and the dogs writhed in agony on the ground, the men fled under their carts and wound themselves, head to foot, in blankets, though the temperature might be in the nineties. The torment might last only a few minutes, but it frequently killed horses and dogs and disabled the men for days.

Sometimes, the approaching swarm could be heard: a high, unbroken and terrifying hum. This gave the drivers time to throw wagon sheets over their animals. Mounted men would attempt to outrun the flying horde. Though they were almost always overtaken, the breeze created by their horses’ panic flight saved them from the worst agony; but they pulled out of the gallop, miles away, with faces and arms streaming blood and with the insects six deep on their ponies. Animals heard or sensed the approach of a swarm before men could, and horses sometimes broke into a dead run without warning, unseating their riders.4

No one was ever surprised by the arrival of the Métis hunters. And the noise didn’t stop when the Métis halted. One might think that some relief for the ears would be appreciated when the camp stopped for the night, but no. On arrival at camp, the fiddles immediately came out and music, singing and dancing could be heard long into the night.

Métis music is described as “crooked,” which refers to their phrasing and the fact that they frequently drop or add notes. Métis music is learned and handed down through the generations orally. There was virtually no practice of teaching the music by reading written notes on paper. A song was learned from listening to an uncle or a grandfather play. Today there are many women who play the fiddle, but in the old days it seems to have been mostly a male purview. The oral transmission of each song came complete with many idiosyncratic musical contours or variations in tune or phrase.

Métis music often contains in-jokes or references. For example, adding a particular flourish in one piece (no matter how discordant it sounds to outsiders) will remind everyone present of an old uncle who played it just that way. Métis fiddle music is distinct from the fiddle traditions of Quebec or the Maritimes and is said to be “more crooked” than they are. Some of the variations reveal underlying First Nation musical patterns. The crooked nature of Métis fiddling may reflect the Indian song structure, which emphasizes more the idea of a continual beat than grouping into phrases as is more common in other fiddle traditions.

Métis music is a creative blend of British and French-Canadian tunes with First Nation influences. Most Métis fiddle music is dance music. The Métis always refer to the songs as jigs, even though their dances include a wide variety of step dances, only a few of which are performed in the traditional jig rhythm of 6/8 time. In fact the use of the word “jig” is a Métis version of the French word gigue, meaning “a lively dance.” The “Red River Jig” was the best known and called, in Michif, “Oayâche Mannin.”

Métis musical instruments were small and portable. That’s because the music followed them on their canoe trips or buffalo hunts or trading trips. Mouth harps, small drums, spoons and fiddles were the common instruments of the nineteenth century. Guitars and accordions were also used in the early days if available.

Dancing was a much-favoured accompaniment to the fiddle music. Most Euro-Canadians hated it, which had absolutely no deterrent effect on the Métis. Their dancing, singing and drumming may have been vexing and disagreeable to Euro-Canadians, but the Métis loved it and often danced through the night until they wore through their moccasins.

Métis songs proclaimed who they were and their beliefs. “We are Bois-Brûles, Freemen of the Plains / We choose our chief! We are no man’s slave!” sang Pierre Falcon in his song “The Buffalo Hunt.” The songs sung in Michif often reflect the Métis love of the irreverent, the joke and the just plain rude. The “Turtle Mountain Song” is a perfect example of this. The song originates in the Métis buffalo hunt. It was sung on the way to the rendezvous at Turtle Mountain and likely dates from the 1820s. It’s a long call-and-answer song perfect for whiling away the time on a long journey. The last verse goes like this:

La Montagne Tortue ka-itohtânân

We’re going to Turtle Mountain

En charette kawîtapasonân

We’re going in a Red River cart

Les souliers moux kakiskênân

We’re going to wear moccasins

L’écorce de boulot kamisâhonân

We’ll wipe our asses with birchbark!

Smell was another accompaniment to life on the hunt. Once contact with the buffalo herd was made, the smell of the herd permeated the camp. Buffalo bulls emitted a reeking odour of musk and the smell followed in their wake. Men and buffalo were very sensitive to each other’s smell and could detect each other at two or more miles.

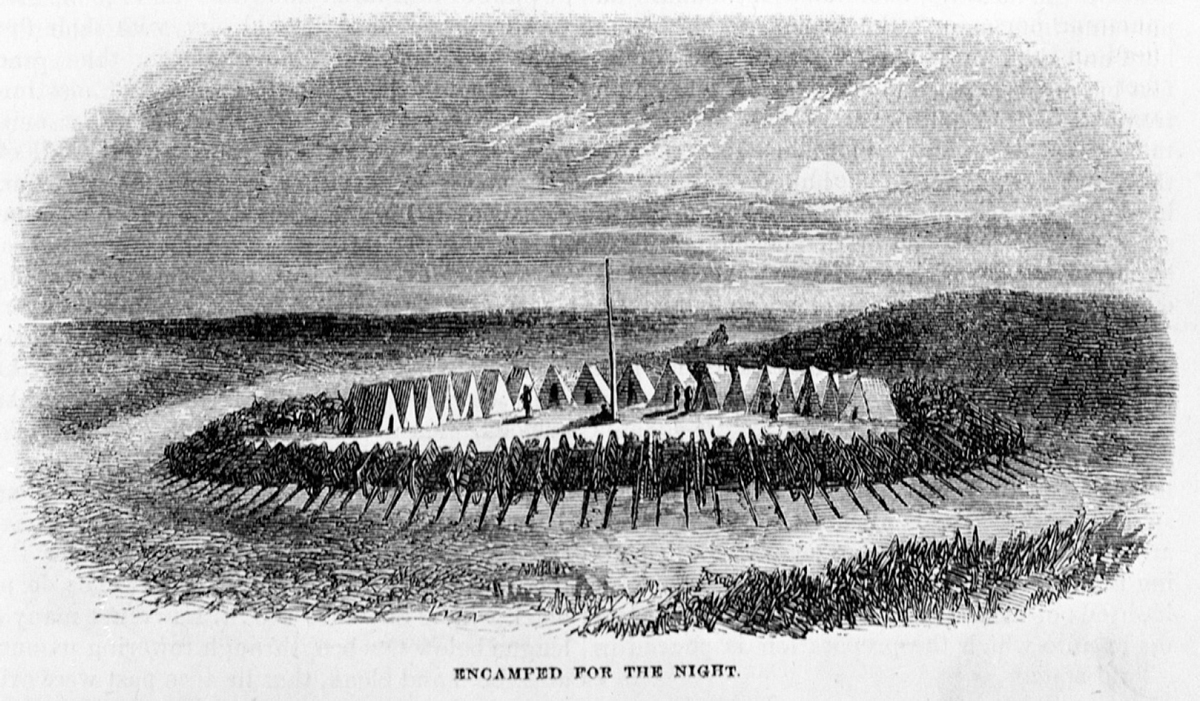

The scouts spread out ahead of the train, searching for buffalo. When the buffalo were sighted, the train was halted. The women took over at this point and began setting up the camp, which they called nick-ah-wah. They arranged the carts in a circle, and put their livestock and teepees inside the circle. Meanwhile the men mounted their buffalo-running horses and rode out toward the herd. At the signal from the captain of the hunt, the men would fan out and charge the herd at full speed.

It was at this point that the horsemanship and marksmanship skills of the Métis shone. Everyone who saw them commented on it. They were commonly said to be the best horsemen in the world, and the most expert and successful of the buffalo hunters in America. When the hunt signal was given, the hunters sprang forward and the herd would stampede. Each hunter singled out an animal, pursued it and then, coming alongside it, would shoot. The speed was ferocious. Once the buffalo was down, the hunter dropped a piece of cloth, a glove or some other token on the dead animal to mark his kill. That was kill number one.

Métis buffalo hunters’ encampment (Glenbow Archives NA-1406)

The hunters shot from the hip, dropped the token and, still galloping at full speed in the middle of the herd, reloaded, selected another animal and shot again. The best hunters could kill ten buffalo at a “course,” but it was more usual for each hunter to bag between three and eight animals. Jerry McKay, armed with a single-barrel flintlock, was said to have killed thirteen buffalo in a single run, a feat that he apparently repeated more than once.

The hunt was exciting and very dangerous. A buffalo could gore a horse, and a fall in the midst of a stampeding herd was certain death. Reloading at full speed was perilous and not a practice for the novice. The men kept their powder loose in their pockets and their bullets in their mouths. While the horse kept charging through the herd, the hunter poured powder into the barrel of his gun, spat in a bullet, smacked the stock of the gun hard on the saddle and shot. Francis Parkman described the obvious danger of the practice:

Should the blow on the pommel fail to send the bullet home, or should the latter, in the act of aiming, start from its place and roll toward the muzzle, the gun would probably burst in discharging. Many a shattered hand and worse casualties besides have been the result of such an accident. To obviate it, some hunters make use of a ramrod, usually hung by a string from the neck, but this materially increases the difficulty of loading.5

The buffalo-runner horse was a prized possession, dearly bought, tended with great care and gorgeously decked out with colourful beads, porcupine quills and ribbons. This prize never drew the Red River cart and was rarely mounted except for the chase. Horses were the most valuable possession a Métis family owned, and they were beautiful horses originally from the southern parts of New Spain.

The Métis habit of pursuing the chase was universally frowned on by Euro-Canadians, the priests and everyone else who observed it. As the following examples show, the disparaging critique of the Métis was relentless and, in the case of those who actually resided in Red River and were dependent on the product of the Métis hunting, hypocritical.

RED RIVER RESIDENT: After the expedition starts, there is not a man-servant or maid-servant to be found in the colony. At any season but seed time and harvest time, the settlement is literally swarming with idlers; but at these urgent periods, money cannot procure them. This alone is most injurious to the agricultural class.6

EXPLORER: The settlement [Pembina] consists of about three hundred and fifty souls . . . they do not appear to possess the qualifications for good settlers . . . most of them are half-breeds . . . Accustomed from their early infancy to the arts of the fur trade, which may be considered as one of the worst schools for morals, they have acquired no small share of cunning and artifice. These form at least two-thirds of the male inhabitants . . . who therefore devote much of their time to hunting . . . experience shows, that men addicted to hunting never can make good farmers.7

OUTSIDE OBSERVERS: The French half-breeds . . . the most unreliable and unprofitable members of society . . . have an utter distaste for all useful labour . . . But as hunters, guides, and voyageurs they are unequalled . . . The two great events of the year at Red River are the Spring and Fall Hunt . . . At these seasons the whole able-bodied half-breed population set out for the Plains in a body, with their carts.8

PRIEST: The greatest social crime of our French Half-breeds is that they are hunters . . . Born very often on the prairies, brought up in distant and adventurous excursions, horsemen and ready marksmen from their very infancy, it is not very surprising that the Halfbreeds are passionately fond of hunting, and prefer it to the quiet, regular and monotonous life of the farmer.9

Patrice Fleury explained that the Métis hunters exercised the greatest care and no waste was permitted. A strict rule of his camp was that the meat and skin were preserved and cured before any more buffalo were slaughtered. According to Fleury, on hunts with fewer groups of families, no more than five or six buffalo a week could be taken. The meat was dried in strips (dried meat) or pounded into small flakes (pounded meat). The bones were broken up to extract the marrow, which was melted and poured over the pemmican before it was sewed up tightly in skin bags. The horns were used for cups, hooks and ornaments. Sinews as fine as thread were used to sew tents, moccasins and pemmican bags made from the tanned skins.

Babiche, the Métis version of duct tape, was made from long thin strips of hide from an old buffalo. They used it for everything. They stored it dry and when they wanted to use it, they soaked it in water and wrapped it around the necessary item. One of its uses was to bind the rims of the Red River cartwheels, which gave the wood greater strength but had no dampening effect on the awful shrieking sound. A babiche-bound cartwheel rim would last a whole summer of hard use.

In the 1840s buffalo robes became a new product of the Métis hunts—so much so that the robe trade began to eclipse the trade in pemmican and meat. The robes were made from the tanned hides of buffalo, complete with their luscious winter wool. As the robes became more and more popular in the United States, they commanded premium prices, which drew increasing numbers of Brûlés onto the Plains for the winter hunt. This new trade in robes depended much on women. It is generally thought that all the preparation of the hides was women’s work. But Louis Goulet said that scraping the hides was men’s work, and that while the men were scraping the hides, the women were cutting up the meat into thin strips for drying. All of this processing had to be done on the spot. This meant that entire families continued to accompany the male hunters on the hunts.

The major market for buffalo robes was not the Hudson’s Bay Company. Buffalo robes were too heavy and bulky for the Company to ship to England profitably. They also had a major deficiency: they could not be dyed. Like the buffalo and the Brûlés, the robes could not be finessed. They stubbornly retained their own character.

Although the Company encouraged the robe trade north of the border, largely because this kept the robes from the Americans, the Company’s low prices were not an incentive for the hunters, who mainly hunted in the United States, to bring the robes over the border and home. So the great majority of the robes were sold south of the border, especially in St. Paul, Minnesota.

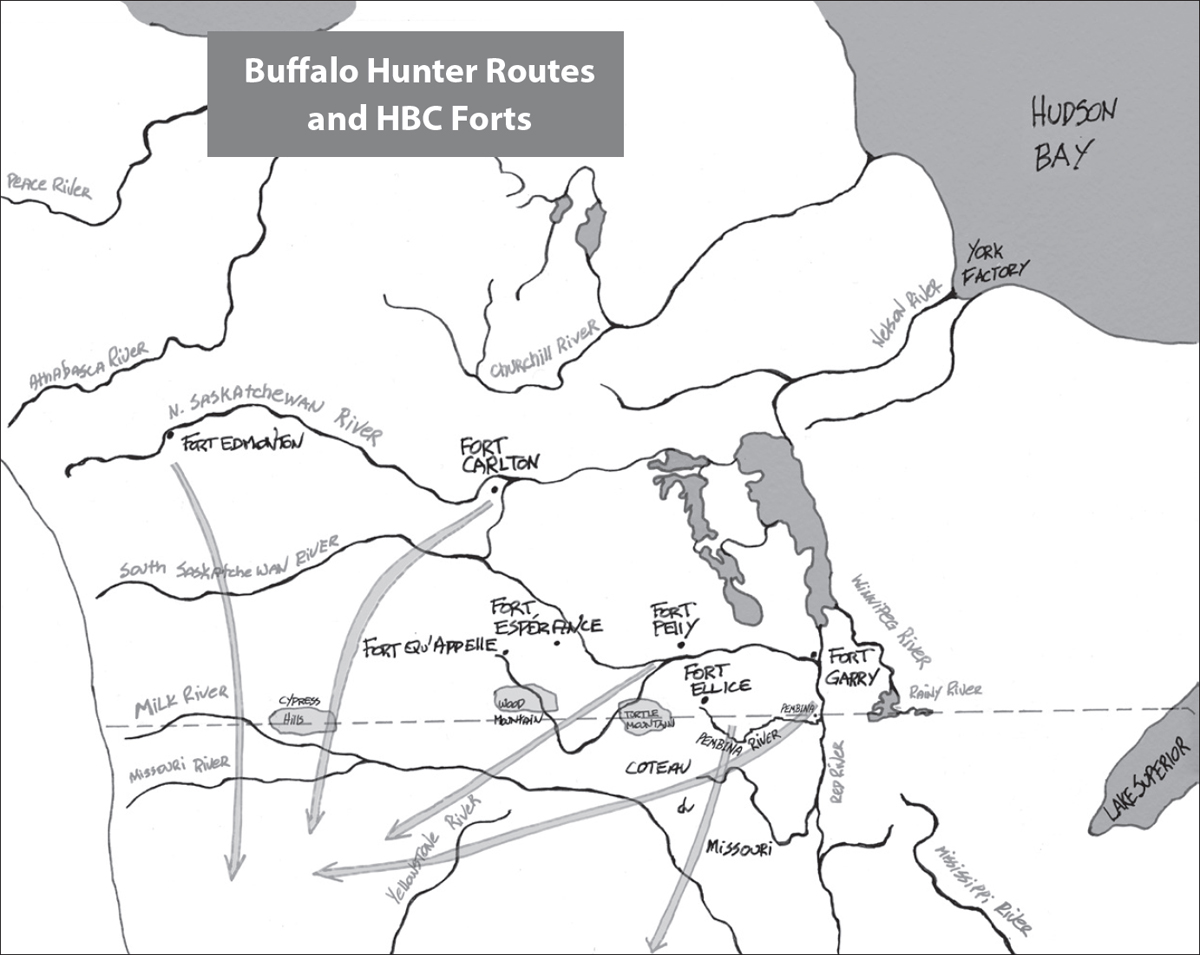

The location of the hunts constantly changed as the buffalo migrated, but the Brûlés were able to identify migration patterns in the herds early on. In 1828 there were Brûlés and Freemen hunting groups that travelled a hundred miles past the Sheyenne River to find the buffalo herds. In the 1840s, ’50s and ’60s, the Brûlés from Red River followed the same routes they had used for fifty or more years. The difference by the 1860s was that they had to travel farther west. As time went on, the hunting expeditions grew in size. In 1822 there were 150 carts in an expedition. In 1840 there were over 1,200 carts and 1,630 people. But the hunting camps were not always large. Patrice Fleury described a camp in the 1860s of about twenty men with their families.

Pembina River was the great rendezvous. In order to obtain easier access to the herds, some Métis from Red River moved back to Pembina in the 1840s and 50s. They much preferred Pembina and regretted relocating to the Forks in the 1820s under the combined pressure of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the priests. In 1816 there were swarms of buffalo to be seen from Brandon House. By the 1850s the herds were farther south and west. In 1859 the buffalo were plentiful in the Plains to the east, west and south of where the city of Saskatoon now stands, which was an area described as a famed buffalo feeding ground.10

In 1845 Father Belcourt described a hunt that left the Pembina River and finished in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1849 Brûlés traders were seen in a group of twenty-five carts travelling a well-known route for the Red River people, along the west bank of the Mississippi River, heading north to Pembina. In 1856 the Bois-Brûlés hunted in two groups, one from Red River and the other from White Horse Plain. The Red River hunters headed to the Coteau du Missouri and even as far as the Yellowstone River. The White Horse Plain Métis generally hunted west of the Souris River and between the branches of the Saskatchewan River.

The buffalo hunt is what fully established the Métis Nation. The wild boys had matured. Grant had taken a gang and turned it into a deadly and efficient hunting and military force. The whole nation, men, women and children, were capable of being called up at a moment’s notice. They were a formidable defensive and attack force, drilled now to obey command.

By the 1830s la nouvelle nation had begun to change its name. The English generally used the term “half-breed.” The French still used “Bois-Brûlés,” but more and more they took to calling themselves Métis, which they would have pronounced “Michif.” They used it also as the name for their language and for their nation—the Métis Nation. Naming was fluid and one individual might add a language descriptor. An English-speaking Métis might call herself an English Métis or a half-breed. Another might say he was a French Métis, a Michif or a Bois-Brûlés. Some used more than one term within the space of a few sentences. Regardless of the name, however, la nouvelle nation, the Métis Nation, was now known far and wide as “the best hunters, the best horsemen and the bravest warriors” of the Plains.11