PAINTING OUT HER NAME

13

The Titmouse Disguised

THE NEW BATTERY was in its place and Dick had spent happy minutes carefully connecting up the wires. It was almost dazzling to look into the cabin of the Teasel. Nobody would have guessed that under those bright and cheerful lamps there was talk of giving up the voyage to the south altogether.

‘It’s like this,’ said Tom. ‘That beast George must have told the Hullabaloos to look for me in the Titmouse or he would never have been so sure they’d got me when he saw the twins towing her down the river. It’s no good my coming with you. The only thing to do is to slip home and stay hid in the dyke.’

‘But if you don’t come how can the Admiral get to Beccles?’ said Dorothea, who thought of the voyage to the south as if its sole object was to take Mrs Barrable back to her childhood’s home.

‘The twins,’ began Tom.

‘They can’t get away for long enough,’ said Dorothea.

‘And where is Dick to sleep tomorrow night?’ said the Admiral. ‘There’s only room for four in the Teasel. We’ll even have to give up the voyage to Horsey.’

‘I’ll lend you Titmouse for that,’ said Tom. ‘It won’t matter so long as I’m not in her … and I shan’t be able to use her anyhow.’

‘Rubbish,’ said the Admiral. ‘Why, in another ten days you’ll be back at school and not able to sail at all. Now listen to me. First of all, you’ve promised to skipper the Teasel. …’

‘But the moment they see the Titmouse …’

‘Listen. Have those people ever seen the Titmouse … really seen her, so as to know her again? No. What can your George Owdon (horrid name) have told them about her? … a small sailing boat called Titmouse. But supposing she doesn’t exist. … Supposing there is no Titmouse on the river. …’

Tom’s eye lit up.

‘Paint her name out?’ he said.

‘Disguise?’ said Dorothea. ‘Oh, why not? It’d be simply lovely. Just the thing for an outlaw to do. Mr Toad got out of prison disguised as a washerwoman. …’

‘We can’t disguise the Titmouse as anything but a sailing dinghy,’ said the Admiral. ‘But we don’t want to.’

‘The trouble is,’ said Tom, ‘there aren’t such an awful lot of white dinghies.’

‘Those people won’t be as well up in dinghies as you are,’ said the Admiral. ‘They’ll look for the Titmouse, and if they can’t find her name they’ll go on looking. I’ve got plenty of white paint just to cover those black letters. And a little turpentine’ll take it off again without making a mess of your boat.’

‘There’s something else we can do,’ said Tom, jumping up. ‘Make her look altogether different. The twins won’t have gone to bed yet. Botheration! The awning’s up in Titmouse. May I borrow the Teasel’s dinghy? There’s just time to telephone from Ranworth. I want to tell the twins to bring a bit of rope.’ A minute later he was rowing away in the dark.

Breakfast was over. Washing up was done. The Teasel, stripped of her awning, was ready to sail. But William, of all her crew, was the only one aboard. Dick and Dorothea were in the bows of the Titmouse cocking her stern up out of the water. Admiral Barrable was kneeling in the stern of the Teasel’s dinghy, with her palette on one hand and a paintbrush in the other. Tom was in the dinghy with her, holding it as steady as he could. The black E of ‘Titmouse’ was vanishing under fresh white paint, as the Death and Glory, with the twins at the oars, Joe in the bows and Bill and Pete in the stern, came out from among the trees.

‘Got that rope?’ shouted Tom.

‘We got him,’ shouted Joe.

‘Whatever do you want it for?’ asked Starboard, and at that moment everybody in the Death and Glory saw what had happened to the name on the Titmouse’s transom.

‘Gee whizz!’ said Joe. ‘If that don’t puzzle ’em.’

‘You won’t know her when we’ve done with her,’ said Tom. ‘Just wait till we’ve got that rope rigged all round her for a fender.’

‘Well, Joe,’ said Mrs Barrable. ‘What about that watcher of yours at Acle? He doesn’t seem to have been of much use yesterday.’

The twins laughed.

‘Him?’ said Joe indignantly. ‘I been down to Acle last night. Bill’s bike. That Robin never see ’em go through the bridge. And for why? You know that fourpence I leave him for the telephone. His mam keep him in bed with a stomach-ache. You wouldn’ think a chap could get a stomach-ache for fourpence. But he done it. He go and buy a lot of dud bananas cheap and eat the lot.’

‘Disgraceful,’ said the Admiral.

‘I’ll stomach-ache him when I get him,’ said Joe.

In a very few minutes the rope had been fixed all round the Titmouse, outside, tied to the rings that had been screwed in there for lacing down the awning. The rope was an old warp that Tom had saved when one of the wherrymen was thinking of throwing it away. It was very thick and dark with age, and when it was fastened on, it made the Titmouse, with her mast stowed, look like a rather neglected yacht’s dinghy. Only those who knew her well could have recognised Tom’s smart little sailing boat.

‘Poor old Titmouse,’ said Tom, as he made her painter fast on the Teasel’s counter.

Already the twins were aboard the Teasel stowing their dunnage in the little fore-cabin. Dick’s blankets had been made into a tight roll and packed into one of the Titmouse’s new lockers. The Teasel’s own dinghy had been taken in tow by the Death and Glory, to be laid up in the Coot Club dyke until the cruise was over. Joe and Bill were resting on their oars waiting to see the start.

‘Look here,’ said Starboard, coming out into the well. ‘If you two want to learn quick you’d better start by being apprentices. Come on, Dick. You’re with me, and Port’ll have Dorothea.’

‘Come along to the foredeck, Dot,’ said Port. ‘We stand by with the peak halyard.’

‘I’ve got the stern anchor aboard,’ said Tom.

Dick and Dorothea did what they were told, and pulled and stopped pulling at the right moment. Up went the Teasel’s sails, and the apprentices and their instructors coiled down the halyards, and tidied the foredeck.

‘I’ll just go ashore and get the bow anchor,’ said Tom, when all was ready for the start.

‘You must let the crew do that,’ said Starboard. ‘If they make a mistake and don’t hop aboard in time, you can always come back for them, but what’ll happen if you slip or something, and the Teasel goes sailing away with Dick and Dorothea?’

‘She’s quite right,’ said the Admiral.

‘Your job, Dick,’ said Starboard.

Dick, in sea-boots, jumped ashore and pulled up the anchor.

‘That’s right,’ said Starboard. ‘Coil the warp. Pull her along. Push her out. Jump! …’

‘She’s sailing,’ cried Dorothea.

Dick, kneeling on the foredeck, was hooking the fluke of the rond-anchor through a ring-bolt. The bushes on the bank were slipping away. Tom, hauling in the mainsheet, headed out into the Broad, went about and brought her racing back for the Straits with the water singing under her bows. In the Death and Glory they were hauling up their own old sail as the Teasel flew by.

‘You’re in charge while we’re away,’ Tom called out.

‘Back the day after tomorrow,’ shouted Starboard.

‘Right-o,’ Joe called back to them.

‘We shan’t see Ranworth again,’ said the Admiral, and Dick and Dorothea looked for the last time at the little Broad where the lurking outlaw had given them their first sailing lessons. In another moment the Teasel was slipping along on an even keel in the shelter of the trees. Then she was clear of the Straits and foaming down the narrow dyke. The dyke had seemed long when they were quanting and towing through it in a calm. It seemed very short today, as they swept through it, and turned into the wind to beat down the river.

‘She isn’t much like a houseboat now,’ said Dorothea exultantly some minutes later, as the Teasel swung round close by her old moorings.

‘She can jolly well sail,’ said Starboard.

‘Can she no’?’ said Port.

‘I wish Brother Richard could see her,’ said the Admiral.

They had a splendid sail to Potter Heigham. Tom and the twins, though they had often sailed with Mr Farland, had never before been in sole charge of anything quite so big. But she was an easy boat to handle, and presently even the apprentices were allowed to take the tiller in turn, each with an older hand standing by in case of need. Those days in Ranworth had been very useful. There was no need to explain why the Teasel had to go first one way and then the other when the wind was against her. The apprentices knew all about watching the flag to see what the wind was doing. Sailing in the Titmouse had taught them a lot.

The chief trouble with the apprentices was that with every bend of the river, winding this way and that between reed-beds and wide, drained marshes, there was something new to be seen. But even that had its good side. With everything being new to the apprentices, Tom and the twins, who knew the river by heart, felt almost as if they, too, were seeing it for the first time.

‘Hullo,’ said Dick, as they came to the mouth of the Ant. ‘There’s a signpost. Just as if the rivers were roads.’

‘Best kind of roads,’ said Port.

Dorothea was having her first turn at the tiller when they passed the ancient ruins of St Benet’s Abbey, with the ruin of a windmill in the middle of them. The Admiral explained what those bits of old wall and broken grey stone arch had been, and Dorothea, even with the tiller in her hands, slipped headlong into a story. ‘If only it was still an abbey … the outlaw would come panting to the threshold and ask for sanctuary, and the Hullabaloos couldn’t do a thing. … Sorry, I really didn’t mean to let the sail flap. …’

The outlaw looked back at the rather large and shabby-looking dinghy towing astern.

‘Nobody’d ever know her, poor dear,’ said Starboard.

‘And with three skippers aboard,’ said the Admiral, ‘what does it matter if one of them has to hide in the cabin while a motor boat goes by?’

‘We’ve done them this time, I do believe,’ said Port. ‘Even that beast George can’t give away what he doesn’t know. He’ll never think of Tom being aboard the Teasel.’

And so, rejoicing in their freedom, the outlaw and his friends sailed on their way, through a country as flat as Holland, past huge old windmills, their sails creaking round, pumping the water from the low-lying meadows on which the cows were grazing actually below the level of the river. Far away over the meadows other sails were moving on Ant and Thurne, white sails of yachts and big black sails of trading wherries. Now and then they met other yachts, running up the river with the wind. Two or three times they met or were passed by motor-cruisers, but not one of them even for a moment made a noise like the Margoletta’s.

Dick was steering when they came to the mouth of the Thurne.

‘Three roads meeting,’ said Dorothea. ‘There’s another signpost.’

‘Do what it says,’ said Starboard. ‘“To Potter Heigham.” Bring her round. The other way’s where you’ll be going when you start for the south. “To Acle and Yarmouth.” Don’t we wish we were coming.’

‘I wish you were,’ said Tom.

‘We all wish you were,’ said the Admiral.

‘But we just can’t,’ said Port. ‘Anyway, this is gorgeous while it lasts. You must let my apprentice have a go again after we pass Womack Dyke. Just to feel what it’s like with the wind free. …’

‘But it’s the beginning of a town,’ said Dorothea half an hour later, as they came into a long water street of bungalows, built on the banks that have been made by dredging the mud from the river. The little wooden houses took the wind from the Teasel’s sails and made things difficult. One moment a dead calm, and then, a good wind slipping through the gap between one house and the next.

They came at last to the boatyards of Potter Heigham, and the staithe and the lovely old bridge built four hundred years ago and maybe more.

‘We’ll never get through it, will we?’ said Dick, who was again at the tiller, ‘even with the mast right down?’

‘You wait and see,’ said Starboard. ‘Where’ll you have her, Tom?’

‘Plenty of room close to the bridge,’ said Tom, who was on the foredeck taking in the jib. ‘And not so far to tow. Look here. You bring her in. Not Dick. Not just yet. …’

Starboard took the tiller, sailed right up to the bridge, and then turned sharply into the wind. With slack sheet and gently flapping mainsail the Teasel came up to the staithe. Tom jumped ashore. A moment later, Port and Starboard were taking their apprentices step by step through all the business of lowering the sail, and then the mast.

‘Better pretend they’ve got to do everything themselves,’ said Starboard. ‘We’ll see nothing goes wrong. Go on, Tom. You go aft to see it comes down all right. Clear away that hatch cover. Now then, Twin, make your apprentice pay out the forestay tackle. Mine’ll look after the heel-rope. Are you ready? Let her come. …’

Tom, in the stern, gave a gentle pull on the topping lift, and the mast, balanced by the heavy lead weight at the foot of it, came slowly down, while its foot rose slowly up through the forehatch. The mast came down so easily that Dick and Dorothea, though they themselves had paid out the ropes, could hardly believe that they had had anything to do with it.

‘Well, who did it, if you didn’t?’ said Starboard. ‘All ready for towing now.’

‘But we’re going to land, aren’t we?’ said Dorothea. What was the good of a voyage if you did not land in the ports you visited?

‘Come along, you two, and William,’ said the Admiral, ‘We can join them above the bridges.’

Both apprentices looked at Tom. They wanted to go ashore, but, at the same time, they wanted to be aboard when the Teasel went through that narrow arch.

‘She can do with a mop round,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll wait to tow through till you come back.’

There was not really much to see at Potter Heigham, and all the serious shopping had been done by Tom at Wroxham the day before. But they had come there by water, under sail, in the Teasel, and that made all the difference. They went to the Bridge Stores and bought picture postcards of the old bridge, and the ancient thatched hut beside it, and one of a boat like the Teasel actually towing through under the low archway. ‘This is our first port of call,’ wrote Dorothea on the card she sent to her Mother, ‘like Malta was when you and father went to Egypt.’ Mrs Barrable bought a few buns, and some bottles of lemonade, ‘to encourage foreign trade,’ as she said, and they were already on their way back to their ship when, just outside the Bridge Stores, they saw an automatic weighing machine which offered, for one penny, to tell anybody his weight and fortune.

‘How can it tell fortunes?’ said Dick.

‘You stand on the platform,’ said the Admiral, ‘and we’ll let it try.’

‘Won’t you, too?’ said Dorothea, after she and Dick had both been weighed, and little cards had slipped out of a slot in the machine, showing their weight in stones and pounds and telling them that Dick was ‘Prudent’ and Dorothea ‘Of a Cheerful Disposition’, and that Dick ‘would Amass Great Wealth’, and that Dorothea ‘would Never be Without a Friend’.

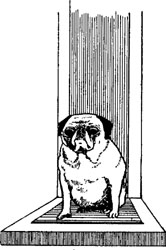

‘Too old for fortunes,’ said the Admiral, ‘and I’d rather not know my weight. Now William …’

‘Oh, do let’s weigh him. Catch him, Dick. Come on, William. Be good. Sit still.’

William rather liked sitting on a platform while everybody looked at him, and the Admiral put in a penny on his behalf.

There was a whirring of wheels inside the machine.

‘Here comes his card.’ Dick took it from the slot. On one side of it was printed, ‘You Weigh 1 st. 3 lbs.’, and on the other, ‘You are a Hard Worker and Should Become Successful’.

hard-working and successful

‘Well done, William,’ said Dorothea.

‘But he never does any work at all,’ said Dick.

‘Perhaps he’s going to, some day,’ said Mrs Barrable, and she gave William a chocolate.

‘You see,’ said Dorothea. ‘He’s being successful already.’

‘Come along now,’ said the Admiral, ‘or those three skippers will be thinking their crew have run away.’

‘Let’s make Tom and the twins get their fortunes told, too,’ said Dorothea, as they turned back towards the bridge. ‘Tom’s ought to be a beauty now that the Hullabaloos are looking for a Titmouse and there is no Titmouse, and not even that horrible George knows anything about the Teasel.’

‘Tom’s fortune will depend on how many shackles and scout knives he has in his pockets,’ said the Admiral. ‘What’s the matter, Dot?’

As usual, two or three people were looking down from the top of the bridge watching the boats at the staithe. Among them was a biggish boy, leaning on a bicycle. He was keeping a little way back from the wall of the bridge, as if he wanted to see without being seen. Just as Dorothea noticed him, he turned away with a smile on his face, jumped on his bicycle and rode off.

‘Dick,’ cried Dorothea. ‘Dick, did you see him?’

‘See what?’ said Dick.

‘George Owdon himself. That boy. There. On the bicycle. The one we saw talking to the Hullabaloos at Horning … the one who said “Serve him right” when the twins were towing the Titmouse past the ferry. …’

But the boy was already riding away along the road, and Dick could not be sure.

‘He’ll have seen Tom with the Teasel, and he’ll go and tell the Hullabaloos where to look for her,’ said Dorothea. ‘Just when everything was going all right.’

‘He may not have seen Tom at all,’ said the Admiral.

But, as they themselves came to the bridge and looked down, there was the Teasel with her mast lowered, all ready to go through, and there were the twins sitting on the cabin roof, and there was Tom himself in full view, never thinking of who might be watching, busy with a long-handled mop cleaning a splash of mud off her topsides.

‘He’ll have gone to tell the Hullabaloos already,’ said Dorothea, looking up the road, where the bicycling boy was already disappearing in the distance.

‘But you’ve only seen him once,’ said Starboard, when Dorothea came running down on the staithe with the dreadful news.

‘Twice,’ said Dorothea. ‘This is the third time.’

‘George Owdon has got a bicycle,’ said Port.

‘Even if he saw you he can’t tell them much,’ said the Admiral.

‘And he’s got to find them first,’ said Starboard.

‘And perhaps it wasn’t him,’ said Port. ‘Lots of other boys have bicycles.’

‘Let’s get out of sight of that bridge,’ said Tom.

Tom in the Titmouse towed. Starboard steered, standing on the counter. The others sat on the cabin roof, ready to use their hands to fend off when under the arch.

‘She’ll touch,’ cried Dorothea.

‘She won’t,’ said Starboard.

‘Do keep all your heads down,’ said the Admiral.

‘Wough! Wough!’ said the hard-working and successful William, and the Teasel slipped through exactly under the middle of the arch, with just about a foot to spare.

‘I can steer now,’ said Dick, as they came out on the other side, and he saw the railway bridge ahead of them, crossing the river with a single span.

‘All right,’ said Starboard. ‘Better learn. Don’t look at anything except the Titmouse. Keep the Teasel pointing at her all the time.’

Above the railway bridge they stopped only to raise the mast and set the sails. Tom would not wait for lunch.

‘Let’s get away from this place,’ he said. ‘Can’t we have it on the way?’

They sailed on. The sun still shone, and the wind blew, the very best of winds for working through the long dyke into Horsey Mere. But, for Tom, life had somehow gone out of the day. If George Owdon had seen him with the Teasel, and told the Hullabaloos, the worst might happen almost any time. Who could tell where those beasts were or how fast they could get about? Lemonade and cheese sandwiches and Potter Heigham buns did not cheer him.

But, of the others, Dorothea alone was sure she had seen George Owdon by the bridge. They grew more and more cheerful as they left the bungalows astern, and turned through the narrow Kendal Dyke into a lovely wilderness of reeds and water, sailed from one to another of the posts that mark the channel, came to a signpost standing not on land but out in the middle of the Sounds, read ‘To Horsey’ on one side of it, reached away through Meadow Dyke, so narrow that they could easily have jumped ashore, and came at last into the open Mere.

This way and that they sailed about the Mere, and, at last, followed another sailing yacht into the little winding dyke, with a windmill at the end of it, just as the map had showed. Here they tied up the Teasel and made her ready for the night. Then, while the Admiral settled down to paint a picture, the others crowded into Titmouse, and went off to row round the reed-beds and see how many new birds they could find for Dick to put down in his notebook. Dick covered two pages with ‘Birds seen at Horsey’, and began a third. Close by the entrance to Meadow Dyke they found him his first reed pheasants, and, at dusk, as they were rowing back to the Teasel he saw his first bittern, unless Tom was mistaken when he pointed it out, just dipping into the shadowy reeds.

After a latish supper Tom and Dick went off to the Titmouse, to sleep one each side of the centreboard. The others settled down in the Teasel.

‘You comfortable?’ said Tom when lights were out.

‘Very,’ said Dick.

‘Bet you aren’t,’ said Tom. ‘It’s just that one bone that’s always a bother. Work round till that one’s comfortable and you’ll find nothing else matters.’

But for a long time after lights were out, people were awake in both boats, listening to at least three bitterns booming at each other, and the chattering of the warblers in the reed-beds, the startling honks of the coots, and the plops of diving water-rats.

It was very late when the Admiral, listening to the steady breathing of the twins in the fore-cabin, leant across to Dorothea. ‘Why are you not asleep?’ she whispered.

‘Supposing that boy was George Owdon,’ whispered Dorothea. ‘Supposing the Hullabaloos came and found us.’

‘It’s all right, Dot. You needn’t worry. An Admiral’s boat is her castle, and they’d have to sink us before we’d give him up.’